Politics

The Deformist Tendency

A new book presents a cogent diagnosis of the ills plaguing American society, but also reactionary prescriptions for ameliorating them.

A review of The New Conservatives: Restoring America’s Commitment to Family, Community, and Industry edited by Oren Cass; 336 pages; Radius Book Group (June 2025)

“The critical issue in my gradual estrangement from conservatism,” Michael Lind wrote in his 1996 memoir-cum-manifesto Up From Conservatism, “was not the New Right but the New Deal.” Which is to say, Lind became disenchanted with American conservatism once libertarian economics became its unchallenged orthodoxy. Now, a New Right has emerged once again, but this time, it is promoting the economic principles that Lind felt were missing from conservatism thirty years ago.

Incited by a cast of insurgent intellectuals, this political movement seeks to put the old Reaganite paradigm of free markets, light regulation, and individual responsibility out to pasture. In recent years, an assortment of populist luminaries have gradually become alienated from a political system in which their combination of moral traditionalism, social conservatism, and economic leftism has not been represented. Today, they seek to construct a new political order, overthrowing the “uniparty” consensus in favour of American global hegemony, unfettered free trade, and high levels of unskilled immigration.

A new book promises to be a valuable resource for this dissident faction. Edited by American Compass founder Oren Cass, The New Conservatives features a series of essays by writers, government officials, and policy wonks about the decline of education and worker power, as well as a defence of tariffs and a “hard break” with China’s menacing state capitalism. The roster of contributors includes US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, National Affairs founding editor Yuval Levin, former American Conservative senior editor Helen Andrews, and the aforementioned Michael Lind. This clever cohort calls for America to abandon the GOP’s free-market fundamentalism in favour of “productive markets, supportive communities, and responsive politics” in order to enhance the country’s power and prosperity.

The New Conservatives speaks powerfully to a new conservative intellectual landscape, the contours of which are still only dimly understood. It is, by turns, a provocative and enlightening document but a remarkably unconvincing brief for the misshapen conservatism currently ascendant in the Republican Party. It presents a cogent diagnosis of the ills plaguing American society, but strange and often reactionary prescriptions for ameliorating them. Its authors are united in their disdain for the managerial class they hold responsible for concentrating power in the hands of corporate giants, stagnating wages among blue-collar workers, and stalling social mobility. This new oligarchy, we are told, is short on wisdom and memory, lacks any interest above self-interest, and aspires only to its own perpetuation. It is responsible, on this view, for “the breakdown in American capitalism” and the profusion of “hollowed out communities.”

By all accounts, the discrete trends of cultural and economic decline are now so advanced that they are working in tandem. In detailing the economic and social woes of Middle America, the authors do not attempt to resolve the academic debate about whether changes in the economy set off a downward spiral in the culture or vice versa. Instead, they argue that government must be responsive to the actual problems of the country (an obvious enough claim until one considers that it was anti-government dogma that pulled America out of its 1970s slump). To this end, the authors Cass has assembled offer a grab-bag of policies to shield workers from the bracing winds of global competition and encourage family formation.

But they also point to a positive governing philosophy. This is a politics of liberty and solidarity that has been lacking on the Right in recent decades. The time, they believe, is ripe for such fresh thinking. The essential proposition here is that government action need not frustrate the well-being of society—on the contrary, it can facilitate it. This is not as radical as it may sound. The American story is not primarily about small government; more often, it has involved limited but energetic use of federal resources to hasten dynamism and social mobility. From George Washington, who used trade policy and industrial policy to protect a budding manufacturing economy, to Abraham Lincoln, who endorsed the Whig program of promoting national development, the growing strength and vigour of the United States has not been a matter of good fortune. (An essay by Wells King about the long pedigree of state-sponsored prosperity and welfare is particularly astute.)

In modern times, though, as social mobility has begun to stall, conservatives have often given the impression that they believe a well-ordered polity consists of little more than a booming stock market and increasing shareholder value. In addition to exacerbating inequality, this arid vision has arguably corrupted our sense of national cohesion and purpose. The party of Lincoln seems to have forgotten that the conservative units of society—family, neighbourhood, faith, and nation—require more of government than a “night-watchman state” simply preserving access to open markets and measuring success solely by the crude metric of GDP. The “little platoons” that make up any free and vibrant society require a government committed to what Edmund Burke called “the care of our own time.”

The writers in The New Conservatives argue that America’s elite has turned its back on the nation, and that the government has left the yeomen masses to fend for themselves in a darkening world. They go on to say that vital national economic interests have been neglected amid the ravages of globalisation, and that worthy national traditions have been left undefended against a progressive cultural onslaught. What’s more, a justified concern with defending national interests abroad has swelled into an indiscriminate habit of projecting American power in quixotic military adventures to spread democracy.

There is a kernel of truth in this narrative, but the big picture it paints is illusory. It portrays the United States as a landscape of material and spiritual degradation, despoiled by the “wreckage of globalization.” It presents the country as an atomised society, the neoliberal political consensus of which has pushed it to the verge of civil strife. It echoes Donald Trump’s curdled belief that “the American Dream is dead.” It contends that America’s post-Cold War foreign-policy record has been a litany of catastrophe now approaching imperial collapse. It closes by highlighting W.B. Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” with its grim prophecy of anarchy “loosed upon the world.”

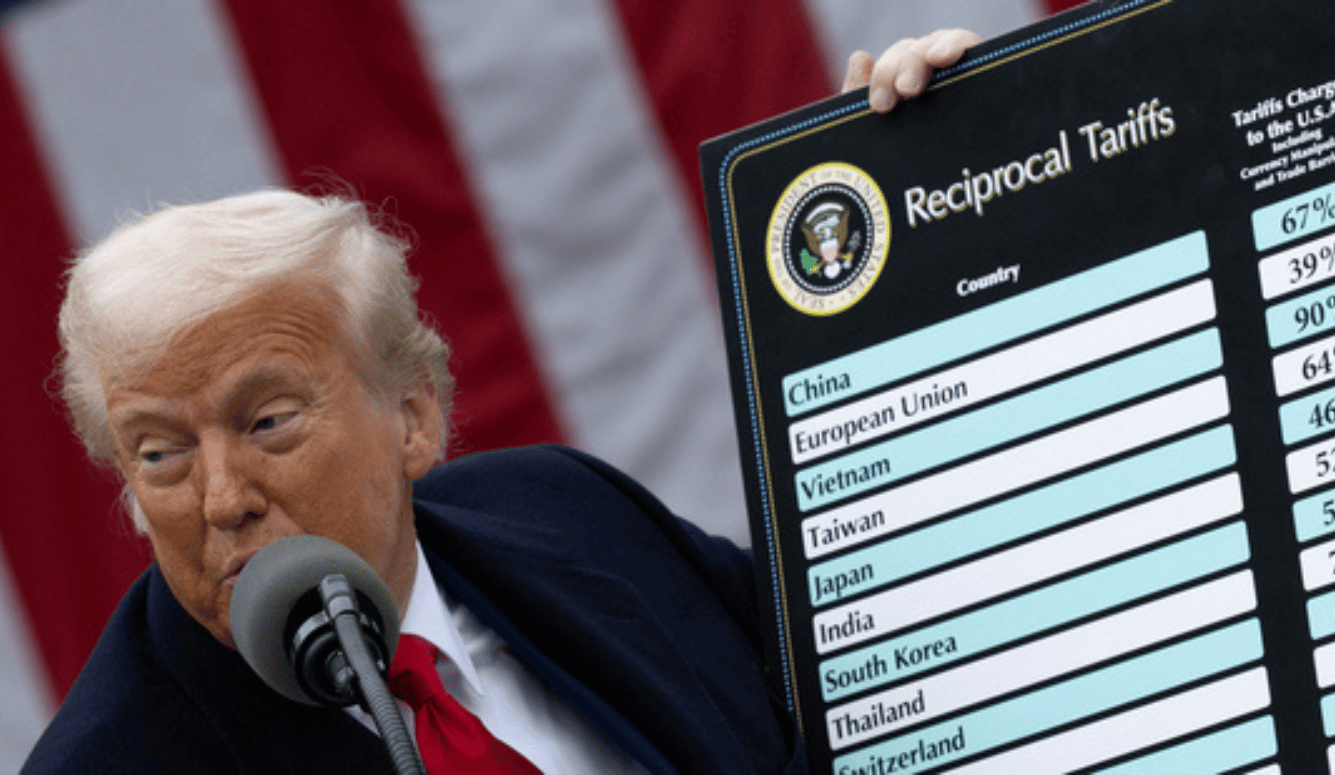

This excessively gloomy reinterpretation of the recent past bears only a faint resemblance to reality, but it is being used to support a radical new social compact. Although Cass & Co. maintain that they reject the “socialist principle” that the state can plan and dictate economic activity, it’s hard to see how their rigid and heavy-handed approach to economic liberty will avoid nasty market distortions. The federal government, they argue, should be reconfigured to curb the excesses of the market that create titanic inequality, but their cure threatens to be worse than the disease. They extol protectionism, limits on the activities of transnational corporations, and industrial policies to bolster manufacturing and national defence. It’s true that a heavy dose of dirigisme once helped to spur the American experiment, but its potential payoff is less evident to a global superpower than it was to an agrarian republic.

What makes this pivot to protectionism particularly unwelcome is that it rests on a series of misconceptions about the fundamental workings of the modern economy. As factory work around the world has become automated, it has put downward pressure on wide employment for the low-skilled in this sector. This has created an influx of technicians and engineers in an industry once dominated by muscle jobs. Since less than a third of American manufacturing jobs today are production roles carried out by workers without a degree, there is simply no longer great potential for well-paying factory work. The benefits of boosting domestic manufacturing are almost certainly overstated. Meanwhile, the logical and probable costs—which have already begun to disclose themselves in the form of rising inflation from President Trump’s tariff barriers—are legion.

This does not mean there is no need to develop resilient supply chains in certain sectors. There is a good case to be made for reindustrialisation in those areas where national security is implicated and dependencies (say, semiconductors and rare earths) are potential chokeholds for our adversaries. One lesson of the supply-chain panic induced by COVID-19 is that it is prudent for the United States and its allies to ensure that crucial infrastructure and—especially in this time of looming great-power conflict—arms and ammunition are sourced exclusively from the free world. But this exceptional case does not justify the zeal for homegrown manufacturing or across-the-board subsidies for reindustrialisation.

The unstintingly morose reading of modernity on the populist Right also incubates a brutal attitude to politics that no serious party can afford. If the rot in American institutions is as deep and extensive as the New Right alleges, it would justify a zero-sum view of partisan competition that not only attacks the Left but deplores any conservative who objects to any of Trump’s policies or methods. As Voltaire’s Candide noted, the British used to think it was useful to shoot an admiral from time to time, to encourage the others. This bloody approach, however, is subject to sharply diminishing returns, and at a certain point, it becomes a considerable liability. The fact that Cass and Vice President Vance recently scorned National Review is emblematic of the drawbacks of this fratricidal worldview.

For all its problems, the United States has built the freest and best society in human history. It retains a vast store of human and economic capital that will not soon be depleted even in the worst of circumstances. Inequality may yawn but life in America for working-class and blue-collar communities has not been an uninterrupted tale of misery and woe. They have benefited from lower prices and ample consumer goods, pulling far ahead of their European counterparts in disposable income and quality of life. The great American middle would arguably benefit from reductions in low-skilled illegal immigration and a more aggressively pro-natalist tax structure. It could certainly benefit from more generous wage subsidies. But the rest of the populist Right’s agenda of protectionism and industrial policy opens the door not to rejuvenation but sclerosis.

On the foreign front, even as an axis of autocracies challenges the liberal order, the United States has the wherewithal to sustain its longstanding strategy of defending an open economic order and an advantageous geopolitical balance by preventing hostile actors from conquering strategic areas of the globe. The ill-fated opening to China deplored by Marco Rubio (along with the vast majority of the political elite) has redounded to the benefit of Beijing’s dictatorship more than the American worker, but this doesn’t mean that the United States is fated to cede the Pacific Rim to the Chinese Communist Party. If it maintains its moral leadership and engagement with allies—and rebuilds its defence industrial base—it can deter or, if necessary, defeat Chinese imperial designs without sacrificing Europe and the Middle East to hostile revanchist powers.

America’s problems are grave enough to warrant solemn concern and urgent action, and many sensible proposals are fleshed out in these pages by Cass and his colleagues. But those problems do not justify the populist Right’s apocalyptic pessimism. The autumnal mood currently fashionable in these circles has bred a revolutionary program—in Left and Right versions—that can only aggravate social and political divisions without doing anything to promote the virtues that undergird personal and national success.

America needs a conservative party that is confident about the American future but also clear-eyed about the challenges that threaten it. It needs a conservative party that resents a sullen and corrupt elite but also grasps that hysterical populism will not check it. A reconfigured conservatism must address the economic struggles of lower-skilled workers as well as the steadily increasing inequality in cultural capital. Such a conservatism could unapologetically defend a one-nation conservatism without yielding to Trumpist demagogy. But that is not the conservatism on offer here.

The authors of The New Conservatives are to be commended for identifying some chronic weaknesses in American government and society. They deserve credit for imagining what a robust nationalism and a cross-racial working-class Right might look like. But when it comes to actual reforms, their program—and the MAGA movement writ large—tempts the fate of national decline they hope to prevent.