Shakespeare

Because the Night Belongs to Lovers

Love is transformative—and in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare is clear-sighted about the fact that that transformation can be for the worse.

Editor’s Note:

At Quillette, we try to balance our coverage of the world’s political upheavals with reflections on the enduring themes of art and human nature. In this lighter piece—first published on her blog The Second Swim—Iona Italia revisits Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream after attending a Sydney performance. Through a close reading of the text and its staging, she explores the character of Helena, the ways in which love can both ennoble and debase, and the strange transformations—comic and tragic—that occur when desire takes hold.

Last summer, I went to see a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the lovely setting of the open-air amphitheatre of Sydney’s Centennial Park.

I had arrived over an hour earlier, so that I could catch the nightly spectacle of bat rush hour, when the air grows sharp with shrieks and the flying foxes fill the sky above Lachlan Swamp, determined crepuscular commuters, released from their roost in bursts, like puffs of scent squeezed out of the bulb of an old-fashioned perfume atomiser. Before the play even began, I had been transported into a topsy-turvy world of reversals. As I climbed the hill towards the theatre, the natural light gradually faded from the sky, making the blue and white footlights of the auditorium ever more alluring. By the time a bunch of young Aussie actors—turned tradies turned mechanicals in a double transformation—drove up a ramp and onto the stage in a golf cart to improvise a prologue, I was more than ready for the magic of theatre.

Amid an excellent production, there was one jarring element and it’s one I’ve experienced in other performances of this play: the depiction of Helena.

Helena is the former betrothed—the ex-fiancée—of the fickle and mercenary Demetrius, a cad with a roving eye, who ditched her when her best friend, Hermia, took his fancy. Despite Hermia’s pronounced dislike of Demetrius and love for another (Lysander), before the play begins, Demetrius has already ingratiated himself with her father Egeus and teamed up with the paterfamilas to force the daughter into marriage. We don’t witness the process by which Demetrius worms his way into the older man’s affections, but Shakespeare gives us some hints of how susceptible the father is to the blandishments of flattery. When Egeus describes the way in which he thinks Lysander—Hermia’s beloved and Demetrius’s rival—has won his daughter’s heart, he reveals that he cannot imagine an affection that is not based on manipulation and trickery:

Thou, thou, Lysander, thou hast given her rhymes,

And interchanged love-tokens with my child:

Thou hast by moonlight at her window sung,

With feigning voice verses of feigning love,

And stolen the impression of her fantasy

With bracelets of thy hair, rings, gawds, conceits,

Knacks, trifles, nosegays, sweetmeats, messengers

Of strong prevailment in unharden’d youth:

With cunning hast thou filch’d my daughter’s heart …

For all his protestations, we sense that Egeus is the one who has been the dupe of feigning and cunning.

Helena, then, is the woman scorned and a truly pathetic figure through much of the play. Right from the outset, we learn that her self-esteem is in tatters. She cannot even hear herself addressed as “fair Helena”—a routine courtesy in the world of Shakespeare’s play—without immediately objecting:

Call you me fair? that fair again unsay.

Demetrius loves your fair: O happy fair!

Hermia and Lysander decide to flee Egeus and the reach of Athenian law to the forest where, as so often in Shakespeare’s comedies, all the chaos and magic happen. They rashly confide their plan to Helena. In her jealousy, Helena betrays the lovers to Demetrius—not in the hopes of ingratiating herself with him, which she already knows is impossible, but in a masochistic desire to use the excuse that she can guide him to his beloved Hermia as way of forcing him to spend time with her, even though she will, she declares, thereby “enrich my pain.” She knows that Demetrius is unworthy of her, but her love is impervious to reason, as she herself admits:

Things base and vile, folding no quantity,

Love can transpose to form and dignity.

Helena, then, is slavishly devoted to a man who treats her with utter contempt—he later even threatens to murder her if she persists in pursuing him. In response, she begs for scraps of affection; she wants him to treat her as his dog:

I am your spaniel, and, Demetrius,

The more you beat me, I will fawn on you.

Use me but as your spaniel—spurn me, strike me,

Neglect me, lose me. Only give me leave,

Unworthy as I am, to follow you.

Our own dog here at home is the princess of the house. Far from being spurned, every time anyone passes her, their voices take on the adoring accents of baby talk and few can resist the urge to caress her ringleted ears and tell her she is beautiful. It is hard to imagine anyone neglecting, let alone striking her. Yet, such is the cultural force of the canine metaphor that even I feel disturbed when Helena desires to be Demetrius’s spaniel, just as I am in the song “Ne Me Quitte Pas,” when Jacques Brel begs to be merely the shadow of his beloved’s dog.

Laisse-moi devenir

L’ombre de ton ombre

L’ombre de ta main

L’ombre de ton chien

So it might seem unsurprising that the beautiful young actress who played Helena—or perhaps the troupe’s director who instructed her—opted to depict her as hysterical, spiteful, oversexed and puerile almost to the point of mental handicap. She depicted her as such a caricature—part foot-stamping toddler, part succubus—that it is hard to imagine anyone ever having been in love with her. This is a not uncommon choice in depictions of Helena. But I think it is a mistake.

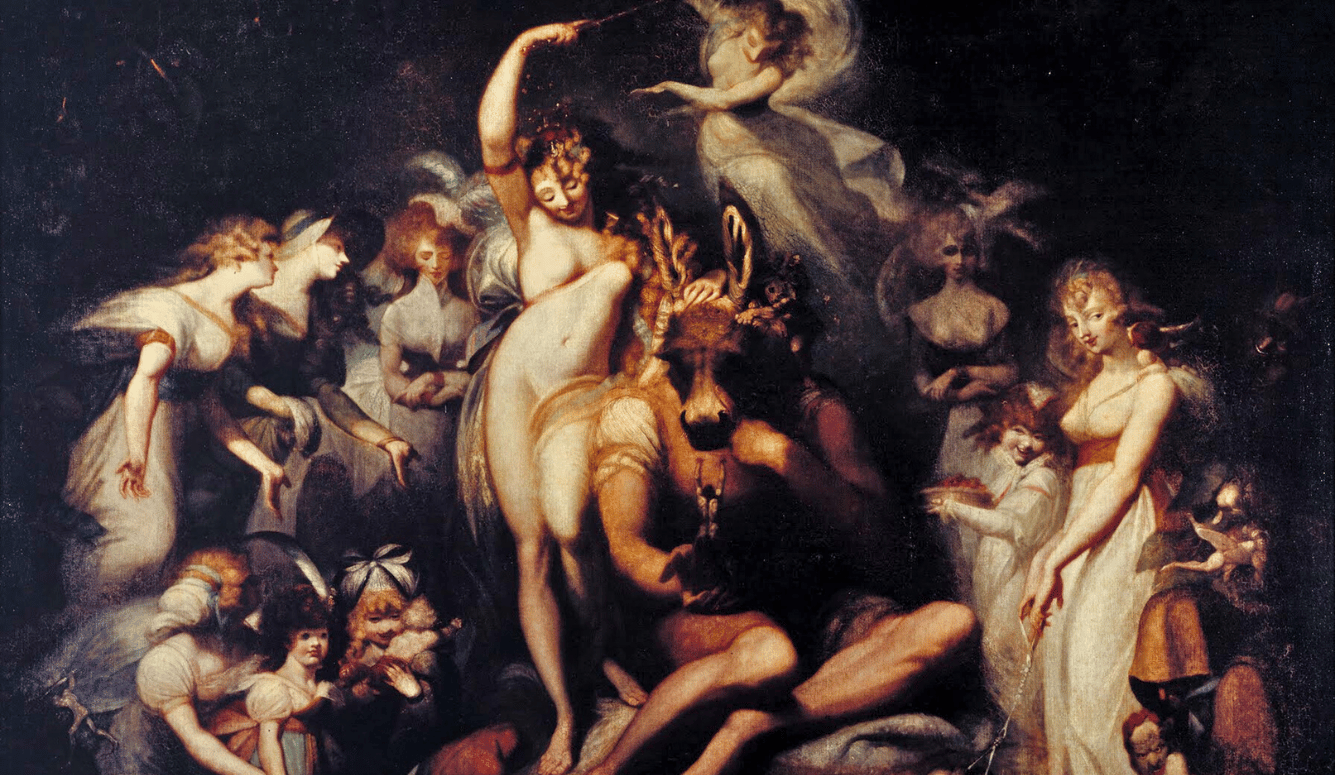

There are indeed deeply self-destructive aspects of Helena’s behaviour. But the lesson of the play is that love is transformative—and Shakespeare is clear-sighted about the uncomfortable fact that that transformation can be for the worse. Love can effect such radical alterations that it can even cause the Queen of the Faeries herself to dote upon a monstrous chimaera, half-man, half-donkey.

Nor is Helena alone in her headlong and foolhardy pursuit of love. The characters in this play adopt various stratagems to force unwilling lovers into—or back into—their arms. Demetrius exploits the laws that govern the suffocatingly patriarchal world of the drama, in which Hermia has three options: marry the man of her father’s choice, be put to death, or enter a nunnery. (Celibacy and death are depicted as equally horrific.) Theseus, on the other hand, resorts to violent abduction. The play, after all, is framed by the marriage preparations and wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta, the bride he won by military conquest when he defeated her army of Amazons. He admits:

Hippolyta, I wooed thee with my sword

And won thy love doing thee injuries.

Oberon meanwhile employs the witchery of drugs to win his tug of love over the young page boy he and Titania each want as an attendant.

Given all this, then, is Helena’s strategy of trying to win the beloved over by slavish, self-abnegating persistence really so insane, in a world where loves are lost and won in so many ways, where every lover cajoles and bargains and tricks? After all, eventually, it works. When Oberon witnesses Demetrius’s scornful behaviour towards his former mistress he decides, on a whim, to teach him a lesson and—various mistakes and misadventures later—Demetrius is in love with Helena again. Puck, the mischievous faerie, squeezes the sap of a magic flower into his eyes as he sleeps and he awakes with a new-found affection for his old girlfriend.

Demetrius is the only mortal who remains in thrall to faerie magic as the play ends. I like to think that Shakespeare, as he scribbled down the final lines, suddenly realised that when the midsummer night ended and the enchantments were broken, the conventions of dramatic symmetry dictated that Demetrius too would have to return to the state in which we found him at the beginning of the play. That clearly could not be. In the wild ceilidh that is comedy, everyone must return to their true partners at the end of the reel. “Ah well,” the bard must have thought, “if I just leave him in his drugged state, surely no one will ever notice.” It’s easy to confabulate an in-universe explanation, though: why should it matter if Demetrius’s love for Helena is the result of faerie magic—isn’t all love the result of faerie magic?

And, besides, even when no external forces—no interfering hobgoblins, no overbearing fathers—are set against us, even when we have a willing, committed partner, love makes us capable of creating our own hell. There is the hell of Helena’s debasing passion—more humiliating than a pair of asses’ ears—and there is also the hell of Titania and Oberon’s quarrels, so violent that they have set nature out of joint, reversing the seasons, just as they are reversed here in my beloved Sydney:

The seasons alter: hoary-headed frosts

Fall in the fresh lap of the crimson rose,

And on old Hiems’ [Winter’s] thin and icy crown

An odorous chaplet of sweet summer buds

Is, as in mockery, set. The spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries, and the mazèd world

By their increase now knows not which is which.

Love can be ugly in this play and it also frequently feels quite arbitrary. The similarity of the play’s two mortal women and two mortal men is repeatedly stressed. It is only to the lover in his or her full ardour that the beloved seems irreplaceable, unique. To us viewers, the young people are very much alike—and this impression of interchangeability is heightened by the theatrical practice of doubling up roles. “I am as well derived as he, as well possessed … my fortunes every way as fairly ranked,” Lysander tells Egeus, describing Demetrius. Hermia and Helena were such inseparable best friends they were almost like conjoined twins, as Helena tells Hermia, in some of the play’s most beautiful lines:

Both warbling of one song, both in one key,

As if our hands, our sides, voices, and minds

Had been incorporate. So we grew together,

Like to a double cherry: seeming parted,

But yet an union in partition,

Two lovely berries moulded on one stem.

The roles of the two men are transposed easily as they shift from one love triangle—in which both are in love with Hermia—to another—when, thanks to Puck’s meddling, both fall in love with Helena. After Puck daubs his eyes with the love potion, Lysander immediately begins to behave as abominably towards Hermia as Demetrius does towards Helena through most of the play. The gallant lover turns cad with disturbing ease. His first words on meeting Helena are to badmouth his former beloved and he dredges up some ludicrously self-deluded rationalisations for his emotional capriciousness:

… I do repent

The tedious minutes I with her have spent …

The will of man is by his reason swayed,

And reason says you are the worthier maid.

When Hermia attempts to hug him, he hisses at her:

Hang off, thou cat, thou burr! Vile thing, let loose,

Or I will shake thee from me like a serpent.

At one point, we are told, he even kicks her away. This is the transformative power of love in its ugliest form. Its course certainly does not run smooth.

At the play’s end, as convention dictates, all lovers are united—or reunited—and quarrels end. Oberon and Titania return to their lovemaking, while their faeries trip through the house of Theseus and Hippolyta, where the bride and groom are sexually joined for the first time and everyone is not sleeping, but loving. The mechanicals have taken their bows. The play-within-the-play, the unintentionally hilarious production of Pyramus and Thisbe, was, we are told, a way for the impatient Theseus “to ease the anguish of a torturing hour,” to make the time pass more quickly as he waited for the chance to finally have sex with his bride.

As the play ended, I was impatient too. My lipstick had been smudged away onto the rim of a wine glass; the ruins of a cheese platter scented the air between my boyfriend and me and, despite having loved the play, I was happy it had ended. I was impatient for the slow Uber ride across the double bridge together amid the ruby brake lights; for the dark, naked seclusion of my bedroom; for the return from Shakespeare’s imaginary Athens to this city at the bottom of the world, surely the most beautiful place that has ever served as a prison. I was impatient to get home, to suspend my disbelief anew, to pledge my faith once again to love. Even though I have woken up with ass’s ears so many times before.

This piece was first published on my blog, The Second Swim.