Politics

Buckley’s Blind Spots

Sam Tanenhaus’s new biography of William F. Buckley provides a rich and nuanced portrait of one of the most consequential public intellectuals in modern American conservative politics.

A review of Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America by Sam Tanenhaus; 1,040 pages; Random House New York (June 2025)

I.

Sam Tanenhaus, author of the acclaimed 1997 biography of Whittaker Chambers and editor of the New York Times Book Review from 2004 to 2013, has finally completed his long-awaited biography of William F. Buckley, Jr.—the contract for which he signed more than 25 years ago! Whittaker Chambers had been a great friend of Buckley’s and a major influence on his political thought, so when the Tanenhaus biography of Chambers came out, the publisher asked Buckley to chair an event in the ballroom of a New York City hotel to promote it. As I recall, Buckley began the evening by telling the audience, “After I opened the manuscript and read it, I knew that I had just completed a masterpiece.”

So, it was not a surprise that Buckley agreed to let Tanenhaus write his authorised biography. Although Tanenhaus is not a conservative of any kind, the Chambers volume indicated that its author would strive to produce a fair and accurate, although not uncritical, portrait, and that he would not use the project as an excuse to score points against his political opponents. Buckley duly instructed his friends and family, associates, schoolmates, and political brethren to cooperate fully when Tanenhaus approached them for interviews and pertinent files they may have held.

What would Buckley have made of the upshot, were he alive to see it? On one hand, it is a magisterial work so compelling and fascinating that I wished I could read it in a single sitting (an impossible task given the book’s length). It will surely win the Pulitzer for biography in 2025 when the prizes are announced next year. Tanenhaus need not fear being relegated to the runner-up category, as his Chambers book was. Although blurbs are not a reliable guide to the quality of a newly published work, on this occasion, the lavish praise adorning the book jacket from authors like Beverly Gage, Max Boot, and Jonathan Alter is well deserved.

On the other hand, the portrait of Buckley that emerges is, in many ways, so unflattering that it has enraged a number of critics on the contemporary Right.

II.

William F. Buckley Jr. was a polymath of unusual erudition. The author of scores of books (including nearly two dozen novels), Buckley was an ardent apostle of conservatism at a moment when American liberalism was ascendant. But he was also an accomplished musician who played the harpsichord, a sailor who entered competitions and spent most summers on the sea, and an avid skier who spent his winters on the slopes of Gstaad after a morning of writing. Most Americans knew him as the host of a weekly television talk show called Firing Line, in which he interviewed and debated a wide range of politicians and intellectuals, most of whom he vehemently but politely disagreed with. (Many of these episodes are now available to view on YouTube.)

Television allowed Buckley to display his not inconsiderable wit and charm. He interviewed prominent socialists like both Norman Thomas and Michael Harrington, but he invited fellow conservatives onto his show as well. He particularly relished debates with ideological opponents like Julian Bond (the young black leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), author Norman Mailer, journalist Christopher Hitchens, Ramparts editor Robert Scheer, and leaders of the Black Panther Party. The only people he would refuse to debate, he told the TV network, were communists lest he lend them legitimacy. Agents of the Soviet Union, he maintained, were not worth engaging with.

Buckley’s other major accomplishment was founding and editing America’s first nationwide conservative magazine. The bi-weekly National Review was the conservative counterpart of the influential liberal publications of the day, including the New Republic, The Nation, The Reporter, and the New Leader. Those liberal magazines all had rather small circulations but they also had the field to themselves until Buckley’s NR came along. Buckley hired a roster of old-style conservatives and ex-communists, including the former Trotskyist James Burnham, the former Communist agent (and accuser of Alger Hiss) Whittaker Chambers, Willi Schlamm, and Frank Meyer. As time went by, he added prominent young conservatives to the magazine’s masthead, many of whom would go on to become political leaders in the new American conservative movement. His prize protégé may have been Gary Wills, who eventually left NR’s ranks and, much to Buckley’s disappointment, became an influential American liberal. Other NR contributors went on to become important American essayists and authors in their own right, like Joan Didion, George Will, and John Leonard, who edited the New York Times Book Review during the 1970s.

Buckley was the scion of a wealthy Connecticut family with a great estate in Sharon, Connecticut, that his father William F. Buckley Sr. named “Great Elm.” However, Buckley Sr. was also a Texan who identified closely with the American South, and after he made his fortune speculating in oil in Mexico and Venezuela, he purchased a mansion in Camden, South Carolina, for use during the cold Eastern winters. He named it Kamchatka, and the neighbouring residents, Tanenhaus writes, embraced the family “as Southerners who had come home.” Kamchatka had previously been the home of a Confederate general and senator who left office when Lincoln was elected President in 1860, but Camden would play an important role in the civil-rights movement.

By the 1950s through the ’60s, Tanenhaus writes, “the institution of Jim Crow—the legacy of slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction—was being shaken at its foundations.” In the ’50s, the nation learned about the brutal murder of fourteen-year-old Emmet Till and massive protests by the black population began to appear across the South. The liberal magazines of the day covered the rise of the civil-rights movement and did what they could to mobilise Northerners in support of Southern blacks. In the deep South, activist efforts culminated in the famous Freedom Summer movement for black-voter registration in 1964. Camden, too, became the centre of a massive resistance movement.

Yet all this political and social upheaval never received a word of positive coverage in the pages of National Review. The reason for this was not complicated. Buckley’s family believed that “race was a settled question” and that racial separation was justified “as a matter of law as well as custom.” The Buckley family, of course, hired black help for their Camden mansion, whom they treated with respect and support. But members of the “Negro” race, as blacks were then called, had to know their place. So, Buckley wrote a number of unsigned editorials in February 1956 defending the South’s “deeply rooted folkways and mores.” The South, he argued, “believes that segregation is the answer to a complex situation not fully understandable except to those who live with it,” just as his own parents and siblings did. He vigorously objected to the Supreme Court’s verdict in 1954 outlawing segregated schools in Brown v. Board of Education, and he wrote editorials arguing that the Court’s decision was not an interpretation of the Constitution but rather “a venture in social legislation.”

In Camden, meanwhile, the Buckley family started and financed a newspaper called the News, which was meant to be a vehicle for the white South’s racist population and their “Citizens’ Councils.” Instead of burning crosses and lynching, the Councils preferred to use “legal threats, economic harassment, and public denunciation” in defence of segregation. In one case, a business owned by a black protestor was destroyed and his family harassed by the Council, after the owner tried to register to vote. As the violence in Camden became more extensive and widely reported, Buckley responded with an unsigned NR editorial on 10 January 1957 in which he argued that “the Northern ideologists are responsible for the outbreak of violence.” He did also condemn the “debasing brutality” of the white population’s behaviour, and for years, that remark remained his strongest condemnation of white violence. He continued to ignore the support provided to the Councils by South Carolina authorities.

One of Tanenhaus’s most stunning revelations is that, in 1956, Buckley dispatched an NR contributor to report on the National States’ Rights Conference in Memphis. The man he sent was one Revilo Oliver, whom Tanenhaus correctly describes as “a fanatical racist and anti-Semite.” The following year, NR published Buckley’s most infamous editorial, titled “Why the South Must Prevail.” The white community, he wrote, had a right to defend segregation because “for the time being, it is the advanced race.” The white South, he wrote, “perceives important qualitative differences between its culture and the Negroes’; and intends to assert its own.” And since NR “believes the South’s premises are correct,” the black population could justifiably have its interests thwarted by “undemocratic” but “enlightened” means. That editorial, Tanenhaus rightly notes, “haunts [Buckley’s] legacy, and the conservative movement he led.” Buckley also believed that if suppression of the black vote violated the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment, then that and the Fifteenth Amendment should be considered unconstitutional—“inorganic accretions to the original document, grafted upon it by victors-at-war by force.”

In July 1957, NR featured an interview with Georgia Senator Richard Russell, who warned that school integration would be a “long insidious step toward” mass miscegenation in the South. During that year’s Little Rock crisis, US troops were sent to Arkansas to protect the young black children (dubbed the Little Rock Nine) who braved white mobs to register in the formerly all-white public school. Buckley and NR were enraged by this interference. In the US, one group had every right to prevail over another if the former was “politically and culturally” more advanced. Given that whites were, Buckley stressed, “the leaders of American civilization” in the South and had a “cultural advantage” over the black population, their interests had to be met. There were no “congenital Negro disabilities,” he wrote; the problem was “cultural and educational.” Therefore, he concluded, the claims of civilisation and culture “supersede universal suffrage.” Whites had a right to prevent blacks from voting, because their votes might “tip the scales in favor of the Negro bloc.” This made disenfranchisement of Southern blacks a necessity, to alleviate white fears of “rule by a Negro majority.”

If one believes the civil-rights movement moved the US towards fulfilling the democratic promise enshrined in its Constitution, then it follows that Buckley’s rationalisations of segregation were deeply un-American. Martin Luther King Jr. may have been a hero to most black citizens and a majority of Americans, but neither Buckley nor NR ever said a kind word about him, while they printed many about the black separatist Malcolm X. In Buckley’s view, Malcolm X was a conservative who hoped Barry Goldwater would win the presidency and sought to advance the black population through hard work, pride, and starting their own businesses. But Buckley hoped that King’s civil-rights campaign would be suppressed by the authorities.

In future years, as journalist Alvin Felzenberg recorded in Politico, Buckley would acknowledge that his old views were wrong and become one of the first conservatives to praise the civil-rights movement. As he famously told Time in 2004, “I thought we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow, but I was wrong. Federal intervention was necessary.” Whether that was sufficient to atone for his inflammatory role at a critical juncture of American history is for readers of Tanenhaus’s biography to judge.

III.

Another area of great concern to the young William F. Buckley was the anti-communist campaign that came to be called McCarthyism, after the junior Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy. Buckley harboured an implacable (and understandable) hatred of communism, which he transferred to the opponents of McCarthyism. But there were many anti-communist liberals, like the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., who opposed both McCarthy and the communists, and who joined the new liberal anti-communist organisation Americans for Democratic Action (ADA). But unlike members of this group, the young Buckley believed that Joe McCarthy was an American hero striving to save his country. He therefore used the NR to legitimise the senator’s campaign and portray him as an admirable figure.

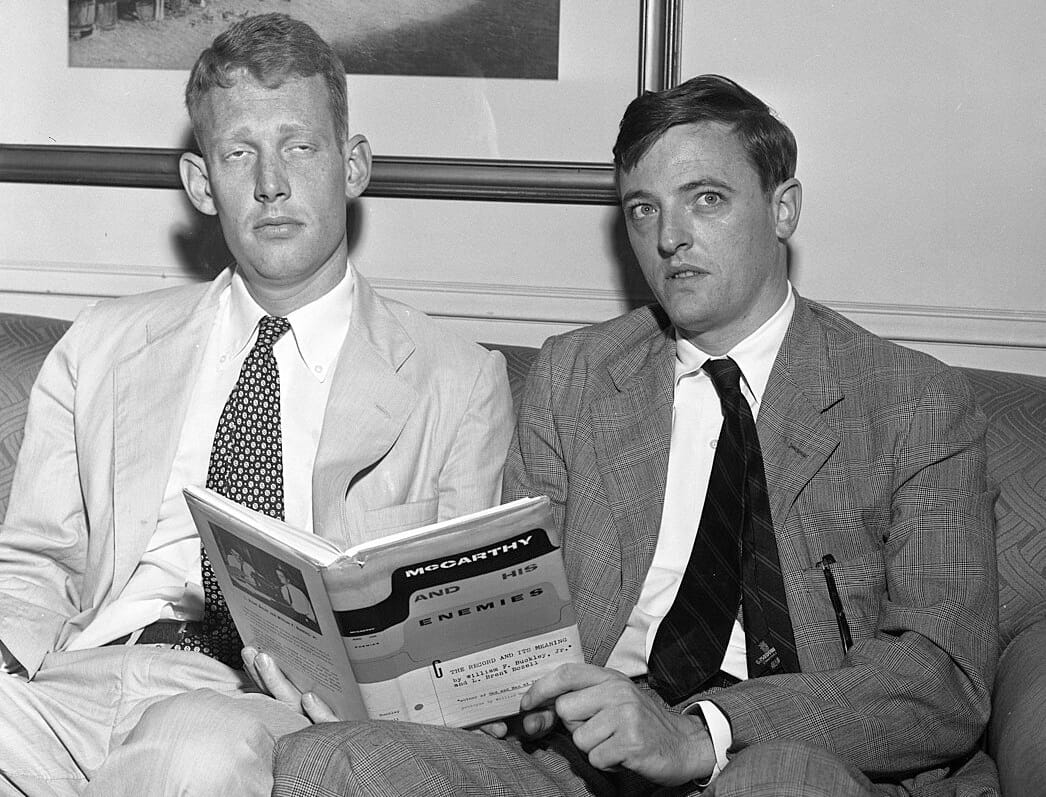

Buckley co-authored a book with his college friend and brother-in-law Brent Bozell titled McCarthy and his Enemies, which received a great deal of attention when it was published in March 1954. By the spring, it was selling a thousand copies a week and it became a national bestseller on all the lists. As a result, it gained the support of the old-line Republican establishment as well as McCarthy’s fans. Buckley and Bozell did not set out to endorse all of McCarthy’s conduct. Instead, Tanenhaus explains, they concentrated on “exposing and routing Communists and their fifth-column allies, the liberals. It would be less a defense of McCarthy than an expose of his opponents and detractors.” Buckley and McCarthy agreed that liberals were enemies of the fight against communism, so Buckley became a willing partner in McCarthy’s “fight for America.”

Buckley and Bozell formed their own anti-communist group called the Independent Committee Against Communists in Government, and under its aegis, they worked in Connecticut to oppose William Benton, one of McCarthy’s main Democratic opponents in the Senate. Like McCarthy, they accused Benton (without evidence) of assisting the Soviet Union in its propaganda war against the United States. Their tactics, Tanenhaus writes, were “the same ones McCarthy was using, with the difference that the brothers-in-law trod a more careful line between smear and outright defamation.” Although they claimed to be doing this in their capacity as private citizens, they actually worked closely with the Republican Party and McCarthy himself, even using Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee money for their efforts. Buckley believed that, whatever McCarthy’s faults, the senator was engaged in a “righteous” crusade and that he was infinitely preferable to his opponents.

The pro-McCarthy book made two charges. First, that America did have enemies within, just as McCarthy claimed, and that these enemies had to be opposed with “social pressure” and psychological warfare. There was a danger that communists would exploit misguided liberals who would destroy America’s democracy in the name of protecting it from red-hunters. Second, although many Americans believed McCarthy was strange and dangerous, the authors saw him as an extension of the Old American Right he had eulogised—the pre-war isolationists in the America First Committee, which Buckley had actually joined at the age of fourteen. If McCarthy eventually became the hysterical demagogue his liberal opponents always said he was, the authors wrote, “it was McCarthy’s opponents who were to blame.” Whatever his shortcomings, McCarthy was leading a “movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks.”

Even when McCarthy was wrong, Buckley and Bozell managed to argue that he was right. When McCarthy falsely accused the scholar Owen Lattimore of being a Soviet spy, it didn’t matter because Lattimore’s own writings showed that he was “shaping the lines of treasonous thought,’’ which made him just as dangerous as an actual spy like Alger Hiss. At some future point, they wrote, “the patience of America may at last be exhausted, and we will strike out against Liberals,” whose actions were plainly “injurious to the interests of the nation,” even if they were made in good faith. McCarthy actually read the book in draft, but told his wife he didn’t understand it (“too intellectual for me,” he complained). Buckley, Tanenhaus observes, “was becoming not merely McCarthy’s defender but his intellectual stand-in.”

Decades later, in 1999, Buckley published a novel about McCarthy titled The Redhunter, and I participated in a forum about the book in the online publication Slate. In one of my contributions to the discussion, I noted:

William F. Buckley Jr. asserts that his novel is true to life “in every conventional way.” And although he claims that he writes not to seek a resurrection of old Joe, since he is candid about all of his warts and the eventual damage he did to the anti-Communist cause, Buckley is of course arguing that despite his faults, McCarthy was “the historical vehicle in America … for an attitude about the Soviet Union I sympathized with.”

Buckley did not let this criticism pass, and he wrote to Slate accusing me of caricaturing his views. (He also objected to my description of the book as “a tough read, heavy and plodding, without any real juice to it. Not the kind of book you want to take to the beach on vacation.”) To this day, I find it hard to understand why Buckley wasted his time responding to these innocuous remarks. I was hardly a prominent commentator, and Slate was not yet a website with a vast readership. Nevertheless, Buckley proceeded to quote from all the positive responses he had received from other writers. The British author Peregrine Worsthorne, we learned, had called the book “simply and beautifully written” and declared that it had succeeded in “casting new light on the dark and squalid tale of McCarthy himself.”

Now that Tanenhaus has confirmed what Buckley actually thought of McCarthy during the 1950s, Buckley’s response to me looks like a case of bad conscience:

My book carefully records and unsparingly ponders the excesses of Joe McCarthy. But the book plants a quandary Radosh does not confront. It is of course, Why did McCarthy get the (qualified) support he got? And not only from fellow Irish brawlers, but from some very choosy Americans such as John Dos Passos and Max Eastman and James Burnham?

The writers Buckley cited were not only ex-radicals, they were also members in good standing in the NR world, and either editors or regular contributors to his magazine. He continued:

The reason McCarthy soared is that he became however briefly the incarnation of the anti-Communist movement, which movement confronted the loss of Eastern Europe, of China, and of nuclear secrets as results of bad strategy, bad judgment, and maladministration. And McCarthy came on to charge that some of the people in government were on the other side, which Mr. Radosh, when loosed from any threat of association with my book, of course knows...

That there were communist spies in America’s government was never denied by any of McCarthy’s liberal anti-communist opponents. But by Harry S. Truman’s presidency, they had been weeded out. McCarthy’s belief, which was accepted and shared by Buckley, that the anti-communist movement was personified by McCarthy himself, was simply and completely wrong.

IV.

Buckley made the related mistake of consistently defending repressive regimes as long as they said they were anti-communist. In Chile in September 1970, Salvador Allende, Tanenhaus writes, “had won a three-man race, making him the [second] Marxist head of state chosen in free and fair elections in the entire hemisphere, possibly the world.” [The first had been Cheddi Jagan, who won free elections held in British Guiana (now Guyana) in April 1953 and became prime minister. In a letter to a Soviet official, US President John F. Kennedy observed that “Mr. Jagan, who was recently elected Prime Minister in British Guiana, is a Marxist, but the U.S. doesn’t object because that choice was made by an honest election which he won.”]

Allende’s rule in Chile came to an end two and a half years later, when a military coup was staged by the army under the command of Augusto Pinochet. As Tanenhaus notes, “mounting evidence” showed that “murder, torture, and disappearances [were] either ordered or sanctioned by Pinochet in the next months and years.” In late 1970, Buckley had a private meeting with the dictator and asked him whether or not he had authorised these killings and murders. With passion and indignation, Pinochet assured Buckley that he “had himself not known about, let alone authorized, any of the random killings and torture.” Pinochet was lying, of course, and Buckley proved that he was as gullible as any person could be. In fact, at least 3,000 Chileans had already been killed by firing squads, beatings, and electrocution, or they had been thrown into the ocean from helicopters.

The evasions and rationales Buckley offered for the crimes of the Pinochet regime were very similar to those used by the political Left to excuse or explain away the brutality of Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba. And Buckley had nothing but contempt for anyone who denied the horrendous methods used by Castro to suppress dissent, or who did not oppose Castro from the day he took power in 1959. I had direct experience of this. On 8 June 1986, the New York Times Book Review ran my assessment of Armando Valladares’s Against All Hope, an account of the author’s imprisonment and torture by Castro’s jailers. “Mr. Castro,” I wrote, “has created a new despotism that has institutionalized torture as a mechanism of social control.” I went on to reproach the American Left for its double standards:

[Had Valladares] not been an opponent of Fidel Castro, the international left would have rushed vociferously to his support. Instead, leftist leaders like the pro-Castro Frenchman Regis Debray and Pierre Schori, a member of the Swedish government’s leadership, kept quiet and urged quiet diplomacy to change Castro’s approval of torture. As for Castro, he publicly said that Cuba “has no human rights problem … there have been no tortures here.”

Buckley read my review, but he did not approve, as I assumed he would. Instead, he chastised me for writing that “it has taken us 25 years to find out the terrible reality” of Castro’s repression. I meant that it had taken this long for Castro’s assault on human rights to gain worldwide attention, which only really began with Valladares’s book and those like it written by other former prisoners. But Buckley wanted to admonish me for not opposing the regime from the moment it took power. “Some of ‘us’,” he bragged, “have known this for about 24 years, reporting on such torture regularly… in National Review.” All right, well, some of us knew about Pinochet’s torture and disappearances of his political opponents from the beginning as well.

Tanenhaus does not spare Buckley’s blind spots, which may explain why some figures on the Right are furious about his book.

I do acknowledge that I was sympathetic to the Cuban Revolution at first, although my illusions did not survive a visit to the country in 1975. When I returned, I wrote a very critical report about my experience and later edited a book about what was going on there. Like many others of my generation, I refused to learn the truth at the start of the revolution. But when we did, honest leftists made clear the nature of reality. Buckley, on the other hand, never did acknowledge his failure to see the monstrousness of the right-wing regime he supported in Chile. Like a credulous communist fellow-traveller, he preferred to believe the Chilean tyrant’s propaganda. Tanenhaus does not spare Buckley’s blind spots, which may explain why some figures on the Right are furious about his book.

V.

How extreme were Buckley’s politics? As evidence of Buckley’s commitment to maintaining the moral hygiene of mainstream American conservatism, it is frequently noted that he expelled the antisemites at NR, followed by the John Birch Society members. But this account is not entirely accurate. As Tanenhaus notes, Buckley maintained a cordial relationship with the paranoid founder of the Birchers, candy magnate Robert Welch, for years. Buckley certainly didn’t agree with Welch about everything, but because Buckley believed Welch was directionally correct on the big questions, he considered him an ally. “We agree on essentials,” Buckley told Welch in a letter on 8 June 1959.

Welch thought that everything evil in American society was the result of conspiracy. Dwight D. Eisenhower, he famously alleged, was actually a communist who engaged in conscious treason. Buckley knew paranoia when he was presented with it, but he was reluctant to denounce Welch. Their differences, he told Welch, were merely “a matter of emphasis.” Tanenhaus writes: “his own reading and Welch’s were thoroughly compatible, especially given the great good Bob Welch was doing.”

In 1963, Buckley received a long manuscript from Welch and handed it to NR’s publisher William Rusher, who gave it to his assistant Jim McFadden to read and evaluate. McFadden’s conclusion, Tanenhaus reports, “was that this guy was a nut.” At this point, Buckley decided to read it for himself. He found that Welch’s analysis of recent history was more than similar his own. The difference—and it is a large one—was that Welch viewed developments, Tanenhaus writes, as “bold, clear outlines of a plot executed with discipline and precision,” and in which much of the US government was implicated. Not only was General George Marshall an agent of the Soviet Union, but even Republican John Foster Dulles was “a Communist agent.”

Welch’s paranoia was most apparent when he concluded that Boris Pasternak’s 1957 novel Doctor Zhivago was a subterfuge planned by Moscow to fool Westerners. Buckley, on the other hand, believed Pasternak displayed a Christian humanism that dated back to Tsarist Russia. Their main difference, Tanenhaus argues, was that “in NR’s view the enemies were liberals [while] in Welch’s they were communists.” But since NR “all but accused liberals of being Communist handmaidens ... the wall of separation between the two positions was so fine as to crumble into dust.” In April 1961, Buckley complained in NR that the liberal establishment had sought to turn the Birch Society into “a national menace,” using Welch’s paranoia and conspiracy theories to smear all conservatives as cranks and extremists.

It wasn’t until later in 1961 that Buckley decided he’d had enough. Welch had gone too far, he realised, and his lunacy was endangering all those with whom he associated. Buckley used the pages of NR to make a considered case for ditching Welch, who risked tarring Barry Goldwater—a politician whom many on the Right saw as presidential material. Buckley’s article was intended to protect the Birch Society’s members, whom he saw as ground troops in the conservative movement, and whose activities would be for naught if their anti-communism were sullied by Welch’s antics. They were not especially grateful, however. But when Welch created right-wing cells modelled on those set up by communists, Buckley wrote to him on 18 December 1958, and said, “We obviously need a conservative apparatus of some kind,” and praised him for building one. And when Goldwater ran his presidential race against Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, these same Birchers served as the GOP’s foot soldiers, especially in California.

In this sense, Buckley was indeed a precursor to Donald Trump, as Tanenhaus argued in a New York Times essay shortly after his book was published. During his lifetime, Buckley praised demagogic figures like Rush Limbaugh, whom he regarded highly. Buckley saw people like this as allies of convenience in the fight against liberalism, and he was always willing to support them and defend them from the shared enemy when the need arose.

VI.

What Tanenhaus admired about Buckley—and here he is on solid ground—was his willingness to engage with political and ideological opponents. He would welcome them onto his television program and usually debate them with civility. Usually, his eloquence and learning ensured a lively contest. His biggest failure in this regard, as most other commentators have noted, was his famous Oxford Union debate with James Baldwin. Baldwin ignored Buckley and simply told the British students how racism was experienced by America’s black population. After Baldwin’s speech, Buckley’s prepared list of talking points was simply ineffective.

Buckley’s most disastrous public fight occurred during the 1968 election season. The ABC television network decided to book Buckley and radical writer Gore Vidal to provide nightly commentary and debate during the party conventions. These discussions would be chaired by the network’s top newsman Howard K. Smith, who had moderated the famous Kennedy–Nixon TV debate in 1960. Needled and provoked by Vidal, Buckley finally lost his temper and insulted him. To the viewing public, Tanenhaus remarks, “it was Bill Buckley who looked and sounded the more effete, with his ornate vocabulary, his drawl and inflections, his arched eyebrow.” At one point, Vidal jibed that Buckley sounded “feline,” a taunt intended to insinuate that Buckley, like Vidal, was gay. (Unsubstantiated rumours abounded about Buckley’s sexuality, but he was heterosexual.)

The simmering hostility finally ignited during the Chicago Democratic convention when Vidal called Buckley a “pro- or crypto-Nazi.” It was the last straw. Buckley’s face, Tanenhaus writes, “contorted with rage” and he seemed to be “about to lunge up from his chair.” Turning to Vidal, he spat:

Now listen, you queer. Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddam face and you’ll stay plastered. … Let Myra Breckinridge [the title of Vidal’s recent novel] go back to his pornography and stop making any allusions to Nazism.

Even in our own era, insults like these are not heard during a serious live television discussion. Howard Smith could only say, “I beg you.” After it ended, Vidal’s friend Paul Newman walked into Buckley’s dressing room. “That was the most disgusting display I’ve ever seen!” he said. “Have you ever been called a Nazi?” Buckley retorted. “That’s political,” Newman replied. “What you called him was personal.” Tanenhaus reports (citing notes made by Vidal from a libel suit against Buckley) that Newman then helped himself to a cold beer from Buckley’s refrigerator, and said, “You’re a male cunt.”

Missteps like these notwithstanding, Buckley’s prominence, wealth, and vast following allowed him to function not just as a writer—his main occupation—but as the organiser and spokesman for a growing new conservative movement. In 1960, he began by helping to put together the first national conservative youth movement—Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). By 1980, he was being credited with responsibility for the victory of Ronald Reagan in the presidential election. NR’s undeniable influence and importance, despite its relatively small circulation, stoked the fires of Reagan’s campaign, and Reagan even revealed that he subscribed to and regularly read NR, and that he agreed with most of its editorial positions.

If not for Reagan’s victory over Jimmy Carter, the conservative movement might never have brought Buckley and NR to such prominence. The movement had treated him with suspicion after he endorsed Richard M. Nixon in 1960, a candidate whom most of the movement considered too moderate. But Buckley was pragmatic as well as ideological, and he understood that political failure would result if a party moved too far ahead of the American people. Ironically, that was also the view of Michael Harrington, who said much the same of his socialist movement. Harrington always argued that socialists had to stand “for the most left-wing policy possible,” but not overshoot the average American by advocating pie-in-the-sky proposals.

One other issue deserves comment. Early in the book, Tanenhaus raises the issue of Buckley Sr.’s notorious antisemitism. He tells the story of how the young Buckley, still in elementary school at the age of eleven, was not allowed to participate with his older siblings in a “prank” endorsed by their father. One night in 1936, they set off for a nearby Jewish resort in Sharon, Connecticut, and burned a cross on its front lawn in the manner of the Ku Klux Klan. That this act was seen by Buckley Sr. and his children as a mere prank, at a time when Hitler’s assault on German Jews had already begun, reveals much about the family’s feelings towards Jews.

Buckley disclosed this incident himself in an important and widely discussed article he wrote for NR in 1992, which then became a book titled In Search of Anti-Semitism. Two years earlier, when he seems to have been contemplating writing about this topic, he remarked that his greatest achievement was “the absolute exclusion of anything anti-Semitic or kooky from the conservative movement.” In 1993, he fired his friend and NR senior editor Joe Sobran for writing columns that Buckley decided were antisemitic. In his book, Buckley reprinted comments made by liberal Jewish journalist Richard Cohen, who wrote, “American conservatism has come a long way since it was polluted by anti-Semitism, and some of the credit is [Buckley’s].” Cohen, as liberal as a columnist could be, was correct in praising Buckley for moving so far from his own family’s dark heritage.

By that point, Buckley had already expressed his unhappiness with former NR writer Pat Buchanan, who revealed his animus towards the Jews in 1991 when he wrote that “the Israel Defense Ministry and its amen corner in the United States” were the only people agitating for war against Saddam Hussein. Buchanan compounded this insult by writing that only young men with names like “McCallister, Murphy, Gonzales, and Leroy Brown” would suffer injury or die in a Gulf war. About statements like these, Buckley remarked, “I find it impossible to defend Pat Buchanan against the charge that what he did and said during the period under examination amounted to anti-Semitism, whatever it was that drove him to say and do it: most probably, an iconoclastic temperament.” For those who doubted Buchanan’s animosity towards Jews, Joshua Muravchik’s seminal Commentary article in 1991, titled “Patrick Buchanan and the Jews,” laid his antisemitism out in convincing detail. Buckley undoubtedly read it at the time.

The Tanenhaus biography is already massive, and it was no doubt even longer in its earlier draft. It seems almost unreasonable to argue that a work this comprehensive ought to have been longer. Nevertheless, the failure to properly acknowledge the efforts Buckley made to repudiate the antisemitism with which he had been raised does feel like a significant and unfair omission—especially since the cross-burning story does make it into the book. The stand Buckley took against the antisemites in the conservative movement cost him friends and required courage. It was one of his most moral moments, and it ought to have received greater emphasis.

Gripes like this one aside, however, the Tanenhaus biography is an astonishing accomplishment that provides a rich and nuanced portrait of one of the most consequential public intellectuals in modern American conservative politics. Buckley emerges as a more extreme and less moderate figure than his reputation and urbane manner suggested, particularly in his younger days. On a personal level, Tanenhaus shows us that Buckley treated people as individuals and that he had many liberal friends, who were politically a long way to the left of him. One of his best friends was the liberal economist, writer, Democratic Party activist, and public official John Kenneth Galbraith, who served in the Kennedy administration and as an advisor to President Lyndon B. Johnson. When Buckley first met Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the preeminent historian of American liberalism and a member of John F. Kennedy’s administration, he told NR readers, “I admire the man who can do as many things as Schlesinger does, and do them so well.” It was never beneath Buckley to praise a political opponent whom he personally admired.

VII.

Why then, have some conservatives taken such exception to Tanenhaus’s biography? Emblematic of this trend is a review in the Wall Street Journal by its brilliant young editorial writer, Barton Swaim. Swaim does manage to describe the book as “a superb biography” and acknowledge that Tanenhaus is a “gifted writer and a diligent scholar.” (How could he not, given the book’s thoroughness?) But then he grumbles that Tanenhaus writes about his subject “in the way liberals have always written about” Buckley. Accomplishments are muffled by condescension and by “envy-laced contempt and melodramatic worries about an authoritarian right.” Like other liberals, Swaim argues, Tanenhaus spends too much time dwelling on Buckley’s “alleged sins,” and trying “to find evidence of racism where none exists.”

Swaim’s critique is mild compared to Helen Andrews’s review in Compact magazine. Andrews worked at NR from 2010 to 2012, and her review is better described as an attack not an honest or careful assessment. She complains that Tanenhaus fails to capture “the grandeur of [Buckley’s] accomplishment or the mechanics of how it was done” because he is “more interested in gossip.” She concludes that he wrote his book “not to understand Buckley, but to discredit him.” However, she also reproaches Buckley for siding with neoconservatives after the Cold War, and for maligning paleoconservative populists like Patrick Buchanan who opposed foreign interventionism, a liberal immigration policy, and free trade. “Populism is a fine tradition,” she writes (ostensibly ventriloquising the MAGA point of view, but also, one suspects, expressing her own), “and Buckley did everything in his power to stop it from gaining a foothold.” That Buckley managed to suppress paleoconservatism where his successors’ attempts to do the same with Trumpism have failed is “in a way, a testament to Buckley’s genius.” Perhaps here, she awards Buckley more power than he actually had to shape the opinion of a newer generation of conservatives.

Unsurprisingly, National Review ran an editorial assessment of Tanenhaus’s biography rather than a book review. Buckley, his successors write, made an “indispensable contribution to defining modern conservatism and its principles” and they criticise Tanenhaus’s book for implying that its subject lacked “depth or seriousness of purpose.” They are also unhappy with the emphasis placed on Buckley’s early defences of segregation (which they acknowledge “were disgracefully wrong”) and complain that not enough attention is given to his change of heart by the 1960s. “It shouldn’t be surprising,” they add, “that WFB, a conservative, would have a reflex to defend his fellow conservatives … [yet] he denounced Robert Welch and the Birchers at considerable risk to this magazine.” Finally, NR’s editors conclude that “Buckley stood for and advanced ideas that have proved their merit,” a conclusion many readers will not find compelling given how many of his own positions Buckley ended up renouncing.

But the critical attacks on the book by some of today’s conservatives only show that Sam Tanenhaus aptly accomplished what a good biography demands—respect for its subject but also tough criticism where it is warranted. I disagree with those who argue that Buckley would have felt betrayed by the work Tanenhaus has produced had he been alive to read it. He might have been angered by some of his biographer’s judgements, but I expect he would have respected and appreciated the accomplishment.