Art and Culture

Gonzo Bros

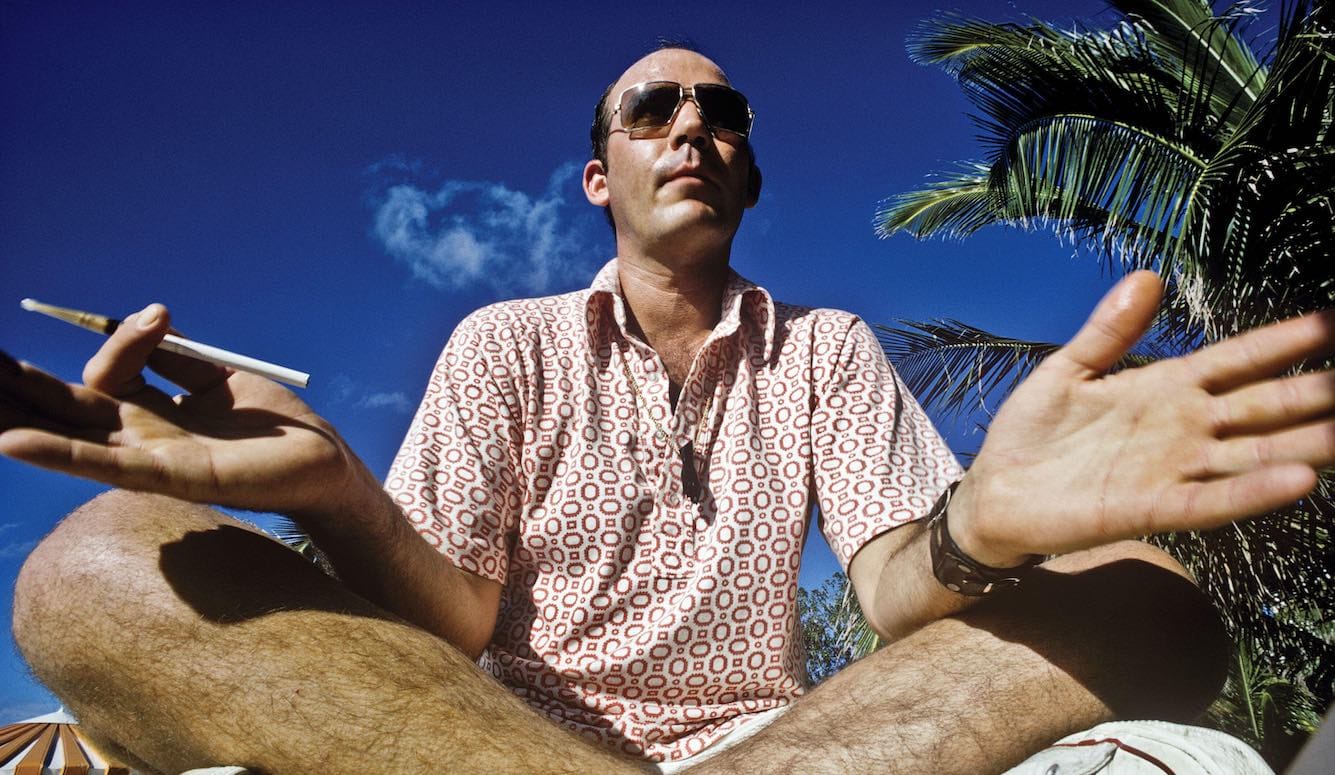

Twenty years after his death, what Hunter S. Thompson’s legacy—or lack of it—tells us about literature and manhood in our current moment.

A full audio version of this article is available below the paywall.

I. The Anxiety Under the Influence

For those too young to have experienced it firsthand, the wide streak of unapologetic masculinity that runs through American letters in the last half of the 20th century must seem like something left over from the Bronze Age. In those far-off days, Ernest Hemingway and his pantheon of bestselling macho disciples loomed over literary and popular tastes like apex predators. The backlash to that era is now so complete that it might be hard to believe that, well into the 1990s, legions of sensitive, bookish young men seized their pens and dreamed ardently of reinventing themselves as stoic tough guys, worldly adventurers, bar room brawlers, big-game hunters, volcanic lovers, reckless drinkers, and/or visionary drug takers. They then cast those experiences into “lean, muscular” prose destined to conquer the world.

To so many aspiring journalists of my generation (b. 1969), Hunter S. Thompson represented the living embodiment of this type of macho writer. A hero of mine from an early age, Thompson was to Baby Boomers and GenX what Hemingway was to the Silent Generation—the kind of writer around whom a cult of personality develops. You didn’t just want to write like him, you wanted to live like him, talk like him, dress like him, smoke the same brand of cigarettes that he did. By the time I was twenty, I had read everything he had written multiple times and could recite from memory almost every line from the 1980 quasi-biopic Where the Buffalo Roam.

By the time I reached adulthood, however, the crass commercial elements of Thompson’s appeal had become difficult to ignore. Like J.D. Salinger, Hunter S. Thompson is a writer best discovered when young. His egocentric writing style plays directly to the sophistry of youth. And the obsessive focus on louche subject matter both excuses and encourages that demographic’s eternal appetite for a raucous good time. Meanwhile, Thompson’s idealistic, Manichean worldview convinces youngsters that they are taking part in some larger struggle merely by reading him. It’s the best of both worlds: the lazy vindication of a lifestyle devoted to staying perpetually high, coupled with the exhilarating sensation that you’re sticking it to the man without ever leaving the safety of your couch.

It’s no accident that Thompson rose to prominence at Rolling Stone magazine during the 1970s by writing primarily for Boomers—a generation at least a decade younger than himself and notoriously prone to gaudy self-indulgence and preening self-regard. Which is not to say that Thompson’s work lacks merit. On the contrary, there’s far more to him than YA marketing (which I’ll get to in a moment). And besides, the young deserve a literature of their own no less than any other age group. I only mention Thompson’s adolescent appeal to explain that, by my mid-thirties, I thought I’d outgrown him. I continued to follow his column at ESPN.com and I would still snap up every new book the minute it appeared, but I told myself that these were mere guilty pleasures—Proustian frolics through my long-vanished youth.

Thompson’s suicide on 20 February 2005 disabused me of any notion that I’d left my childhood hero behind. His death hit me like the loss of a parent. I couldn’t concentrate on work and kept bursting into tears at inopportune moments. Then, as the days passed, an irrational rage joined the sorrow: How could he do this to me? I found myself thinking. How dare he?! The rational neocortex section of my brain knew that I had no personal connection to Hunter Thompson whatsoever, yet the emotional hypothalamus part persisted in this bizarrely personalised grieving. Never before or since has the death of a public figure affected me this way. It wasn’t until years later when I read The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker’s invaluable 1973 compendium of Freudian psychoanalytical theory, that I understood what had happened. Thompson’s passing had deprived me of what Freudians call a transference object.

In brief, transference is a psychological coping mechanism that emerges from an axiomatic truth: no one creates themselves from whole cloth. Our first transference “objects” are our parents, who appear to an infant’s eyes as nothing short of gods, miraculous beings able to control reality in ways that inspire awe. We study them closely, learning the magic spells of language, cause-and-effect, and how to turn on the television. As we grow, we embrace additional transference objects: older siblings, friends, religion, teachers, SpongeBob SquarePants. And all the while, we are watching, imitating, improvising, and searching for patterns of being that we can adopt as our own.

This process accelerates in adolescence. The zeal with which teenagers seize and discard the transference objects of music, dress, celebrities, social cliques, gender identities, sports teams, slang, etc. is well known and often the subject of humour. But it is no laughing matter to the youth, now at an age at which the cold realities of life in an indifferent universe can no longer be wished away. These fixations function as load-bearing psychic architecture—coping mechanisms that help to ease the anxiety, pain, boredom, and confusion inherent to existence. In other words, teenagers seek from the culture around them the godlike comforts and guidance they received from their parents as toddlers.

Where at first transference offers adolescents visions of what they might become, over time transference eventually consoles adults over what they’ve failed to achieve. After all, most of us never come close to realising our dreams. We end up as background extras trapped inside grand narratives over which we exert negligible control or impact. To compensate, we cling to something that makes us feel special. It could be a career, family, hobby, or ideology. It often centres on a single person or leader onto whom followers project extraordinary or even magical powers. Transference, said Jung, is “always trying to deliver us into the power of a partner who seems compounded of all the qualities we have failed to realise in ourselves.” As such, transference explains every weird permutation of celebrity culture, every cult, every bizarre, blood-soaked political or religious crusade history has ever witnessed.

Young, aspiring writers tend to choose well-established virtuosos as their transference objects, the way I did with Thompson. But why do some celebrated writers seem to inspire more of this cult-like devotion than others? Gender likely plays a role here. Young people make these choices at a stage in life when they are asking themselves what it means to be a man/woman. Susan Sontag, one of Thompson’s contemporaries, had the same kind of influence on would-be late 20th-century female writers as Thompson had on male ones. Asked to explain the source of the fanatical veneration that Sontag inspired, a close friend and memoirist concluded: “And of course it had everything to do with gender. It was such an unusual life for a woman. I mean, if you think about it, she was pretty much the only woman of her kind.”

One downside of the sort of relevance Thompson and Sontag achieved is a legacy often more biographical than artistic. Almost everything written about Thompson has focused on his life and personality and excluded or minimised the published work, its place in the Anglophone canon, and its impact on journalism and literature as a whole. Moreover, little has been said about what the disappearance of writers like Thompson means for literary culture and societal ideas about masculinity—or indeed for storytelling itself. But before fleshing out those subjects, some context is necessary. Let’s go back to that previous millennium, a time when being a journalist was actually cool.