American History

The Firing of Wolf Ladejinsky

What a Cold War scandal can teach us about democracy.

Most people have never heard of Wolf Ladejinsky. However, his 1954 case provides a cautionary tale. Ladejinsky lost his job because the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) considered him a security risk—mainly because he was born in Ukraine, which was then part of the Soviet Union. The evidence cited against him was both extremely weak and constantly changing. Ladejinsky’s struggles and eventual triumph offer insights into the fragility of American constitutional rights and civil liberties under rising authoritarism.

Ladejinsky was born in 1899 in the Ukrainian town of Dnipro, then part of the Russian Empire, to a well-off Jewish miller and grain merchant. As a boy, he worked in his father’s flour mill before receiving the equivalent of a junior college degree in nearby Zvengorodka. The Russian Revolution derailed his university plans, however. The Bolsheviks confiscated his family’s properties, thus plunging them into poverty.

Between 1917 and 1920, Bolsheviks, White Russians, and Ukrainian nationalists fought for control of Dnipro. Meanwhile, pogroms swept through Ukraine; according to one tally, some 1,200 antisemitic attacks took place in more than 500 towns, killing an estimated 30–60,000, including Ladejinsky’s only brother. Ladejinsky was selected by his family to escape, while his three sisters remained to take care of their elderly parents. For thirty days, he slogged his way through the Russian winter, mostly on foot. When he reached the Dniester River, he used the last of his money to pay smugglers who helped him cross the frozen water into what was then part of Romania.

Ladejinsky worked at a flour mill in a border town until he had saved enough money to reach Bucharest, where he became a baker’s apprentice. Eventually, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) offered him clerical work. An amiable official at HIAS gave him advice he never forgot: “Go west, young man,” a line he later learned was from Horace Greeley. He took a ship from the Romanian port of Galatz to Hoboken, New Jersey, arriving in the United States penniless but determined to begin a new life in his adopted country.

During his first five years in America, Ladejinsky often worked shifts at a factory. But within five years, he had mastered enough English to resume his education, this time at Columbia University. He ran a newspaper stand to pay for his tuition, earning about US$15 a week, just enough to cover his education and basic needs.

In 1928, Ladejinsky became a naturalised US citizen. That same year, he also completed his B.S. from Columbia and enrolled in a master’s program in economics. In 1930, he was offered a job as an interpreter for Amtorg, the Soviet trade agency in New York. The Depression had made jobs scarce, and the US$40-a-week salary was almost triple what he earned as a newspaper vendor. Amtorg dismissed him without explanation less than a year later. Undeterred, Ladejinsky returned to selling newspapers. In 1932, he completed his M.A. in economics and began work towards a PhD. In 1934, he published an article in Political Science Quarterly entitled “The Collectivization of Agriculture in the Soviet Union.” Though he never completed his doctorate, the article established his reputation as an expert on Soviet agriculture. Coupled with his academic research, his experiences in Ukraine—where the communists had exploited the slogan “land for the landless” while implementing forced collectivisation that essentially enslaved peasants—had given Ladejinsky unique insights into the vital role that land reform can play in ensuring political stability in a troubled region.

At Columbia, Ladejinsky met the economist Rexford Tugwell, who advocated using agricultural planning to alleviate rural poverty. As part of Franklin Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust,” charged with developing New Deal policies, Tugwell helped create the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which increased agricultural prices by reducing production. Tugwell was a major influence on Ladejinsky. Impressed by the younger man’s intellect, Tugwell offered him a position at USDA’s Office of Foreign Agricultural Relations (OFAR), where Ladejinsky worked for several years, publishing extensively on Soviet collective farming.

Ladejinsky was thankful for the opportunities his adopted country gave him. In a letter to his friend James Russell, the Farm Editor of the Des Moines Register, he comments,

I arrived in the States at the age of 22 without knowledge of the language, money, friends, etc. But I had the country to fall on and all it has given to the generation of immigrants in the past. I have taken, and I have given in return to the best of my ability—and with but one guiding thought in my mind—the welfare of the United States.

By the end of World War II, Ladejinsky was widely recognised as USDA’s foremost expert on land reform. But his greatest impact on American foreign policy was yet to come.

The US government sought to establish a prosperous, democratic post-war Japan and combat the influence of communism there. At the time, nearly half of Japan’s population lived in rural areas, and most of the cultivated land was worked by tenant farmers. There was widespread rural poverty. American officials worried that the economic disparity between absentee landlords and tenant farmers could spark instability and make communism seem appealing, while this feudal dependency hindered the development of democracy.

Ladejinsky’s relevant expertise soon attracted the attention of the US military. In 1944, he authored the agricultural section of the Civil Defense Guides for Occupying Forces. In late 1945, he collaborated on a memo to General Douglas MacArthur, proposing radical land reform based on his own concepts. These recommendations convinced MacArthur of the importance of land reform in Japan. On 9 December 1945, his office issued Directive #411, which instructed the Japanese government to submit to a rural land reform program designed to ensure that “those who till the soil of Japan shall have an equal opportunity to enjoy the fruits of their labor.” Later that month, Ladejinsky joined MacArthur’s command in Tokyo. Despite concerns that his Russian accent and foreign birth would limit his effectiveness, Ladejinsky became one of the chief architects of the sweeping land reform program that was enacted by the Japanese Diet in October 1946.

The reform limited the amount of farmland each individual household could own and forced absentee landlords to sell any land in excess of that amount to the government at fixed prices. The government then sold this land to tenant farmers at those same prices. Japan’s postwar inflation had reduced the value of the yen, which made it easier for farmers to repay their own loans, while devaluing the compensation received by the landlords. Approximately six million acres—one-third of Japan’s cultivated land—were transferred under this program.

Japan established farmers’ associations to provide new landowners with seeds, fertiliser, loans, technical support, and marketing assistance. By 1950, around 4.7 million tenant farmers had acquired land, thus destroying the landlords’ hold on rural power. Land reform created a class of conservative small-scale farmers focused on increasing production rather than on revolutionary politics. These newly empowered farmers strongly supported the conservative Liberal Democratic Party.

The program provided millions of farmers with land titles and effectively stopped the spread of communism in Japan. In 1949, the Japanese Communist Party won 35 Diet seats and nearly ten percent of the vote; by 1952, they had lost all their seats. Novelist James Michener called Ladejinsky “communism’s greatest enemy in Asia,” while MacArthur declared, “The land reform program did more to cut the ground from under the Japanese communists than any other measure taken during the Occupation.” Ladejinsky was modest about his own role in this, noting that many Japanese people had advocated land reform since the 1870s and claiming that “the United States only acted as a ‘midwife’ to its execution.” On the strength of his achievements in Japan, Ladejinsky became a sought-after expert on Asian land reform. His concepts also influenced successful reforms in Taiwan and South Korea.

In 1950, the US Department of Agriculture once again loaned Ladejinsky out, this time to the State Department, where he served as the agricultural attaché to Tokyo. His mission there—to expand the Japanese market for US agricultural exports—was a success. By 1954, US agricultural exports to Japan had surged to nearly US$480 million—25 percent of total US agricultural exports.

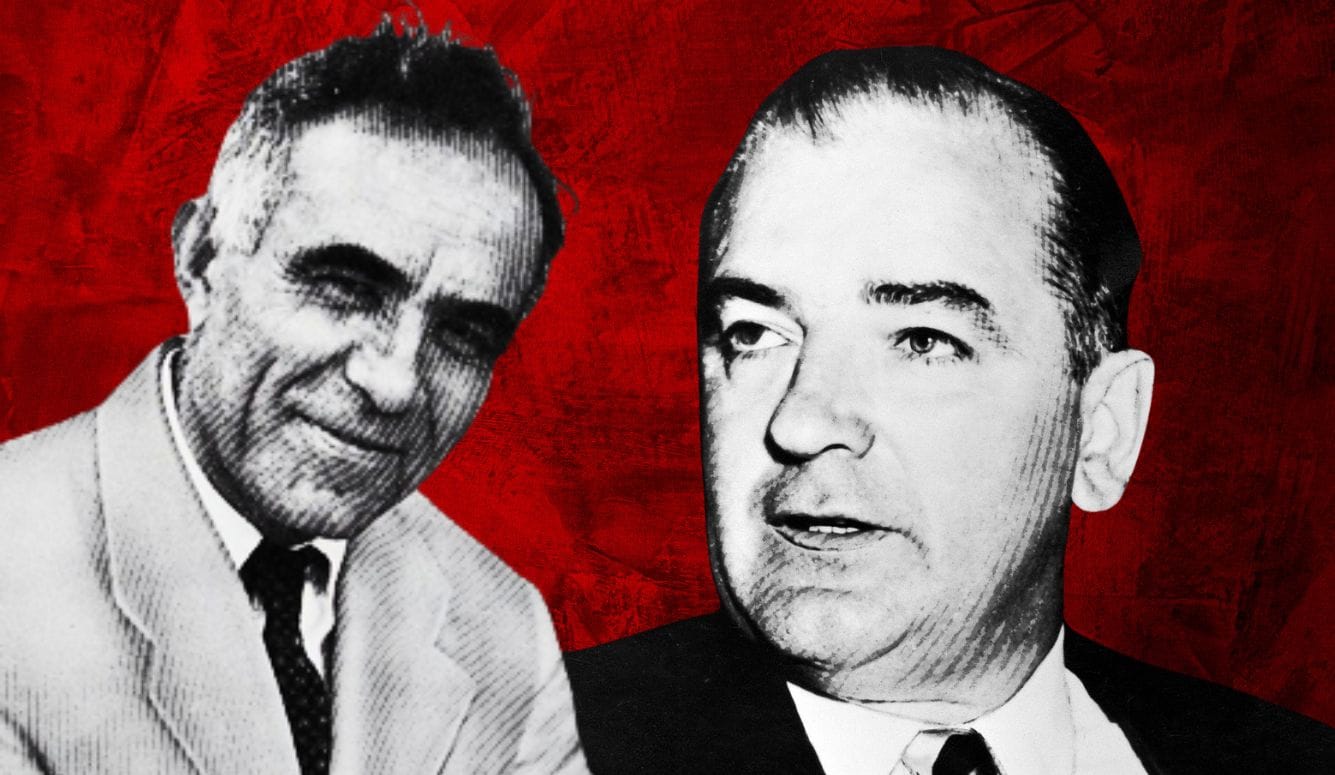

By 1954, the influence of Senator Joe McCarthy was already waning. On 2 December, the Senate voted to censure him for conduct unbecoming a senator. But it was the Ladejinsky affair that ultimately diminished McCarthyism’s broader appeal.

Ladejinsky was not a marginal figure. He was a key architect of history’s most successful land reform program and helped reshape Japan into a modern, democratic country. Yet, amid the lingering paranoia of the McCarthy era, his achievements meant little, given his strange name, accent, immigrant status, and Soviet origins. Ladejinsky was targeted by the Eisenhower Administration’s Secretary of Agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson, an ardent anti-communist who had somehow remained unfamiliar with Ladejinsky’s considerable accomplishments.

On 10 March 1953, Benson dissolved the Office of Foreign Agricultural Relations (OFAR) and established the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS). Effective 1 September 1954, agricultural attachés, including Ladejinsky, were transferred from the State Department back to USDA. During a December 1954 visit to Washington, D.C., in preparation for his return, Ladejinsky—who still held a valid State Department security clearance—was abruptly fired by USDA.

Initially, USDA claimed that Ladejinsky was unqualified for his position because he lacked a background in US farming and thus could not effectively represent American agricultural interests abroad—an implausible rationale, given his documented success in Japan. Soon afterwards, however, a new justification was mooted. Ladejinsky was labelled a security risk, on the grounds that he had briefly worked as a translator for the Soviet Amtorg Trading Company and that in 1939, he had visited his sisters back in Dnipro. The fact that he still had family members living in what was then part of the Soviet Union was cited as evidence that he was vulnerable to blackmail. An antisemitic acquaintance of his also sent the USDA a defamatory letter claiming that Ladejinsky had communist leanings.

News of Ladejinsky’s dismissal broke just before Christmas 1954. Civic leaders, public officials, and the media all sprang to Ladejinsky’s defence. On 18 December, investigative journalist Clark Mollenhoff of the Des Moines Register launched a series of articles on the firing, which dominated headlines for weeks. Many other publications also covered the story extensively, including the New York Times and the Washington Post.

Support for Ladejinsky came from across the political spectrum. The US Ambassador to Japan, John Allison, expressed his support, as did author James Michener. Republican Congressman Walter Judd and Democratic Senator Hubert Humphrey both spoke out in his defence, in a rare moment of bipartisan agreement. Editorial boards across the country criticised the decision. Herbert Block (“Herblock”) mocked Secretary Benson’s actions in widely circulated political cartoons.

Wolf Ladejinsky became a household name and a symbol of McCarthyism’s excesses. Negative publicity about the incident spread worldwide, damaging the United States’ reputation. The backlash embarrassed the Eisenhower Administration. In early January, President Eisenhower announced that Ladejinsky would be hired by the Foreign Operations Administration (FOA), the predecessor to USAID, as an agricultural advisor in South Vietnam. FOA Director Harold Stassen granted Ladejinsky a new security clearance six days later. Eventually, under mounting pressure, Secretary Benson withdrew the “security risk” designation—though he continued to defend USDA’s original decision. Ladejinsky spent the last twenty years of his life quietly working on land reform issues in Asia. He died in 1975.

Ladejinsky’s case led to the decline of McCarthyism in American society. As Senator Humphrey, who led the bipartisan commission to investigate Ladejinsky’s dismissal, commented, “the Ladejinsky case forced the partisan politics out of the security debate and made it possible for my committee to hold hearings in a sane atmosphere and convince Republicans as well as Democrats of the need for a bipartisan review of the whole security program.” Humphrey’s committee concluded that Dwight D. Eisenhower’s security services did not do enough to protect the rights of federal employees. The Eisenhower Administration eventually amended its security procedures, ushering in a more tolerant period.

Wolf Ladejinsky’s story illustrates how easily fear, prejudice, and political expediency can erode democratic norms, while demonstrating that fast and forceful collective action can counter authoritarian excesses. These are lessons that matter now more than ever. They remind us that democracy depends not only on laws and elections, but on a commitment to truth and fairness, principles that can be most vulnerable during times of political anxiety. The Ladejinsky case teaches us that to safeguard democracy we need a free and vigilant press and the political will to band together to fight abuses of power and democratic backsliding.