Politics

An Evening in Neukölln

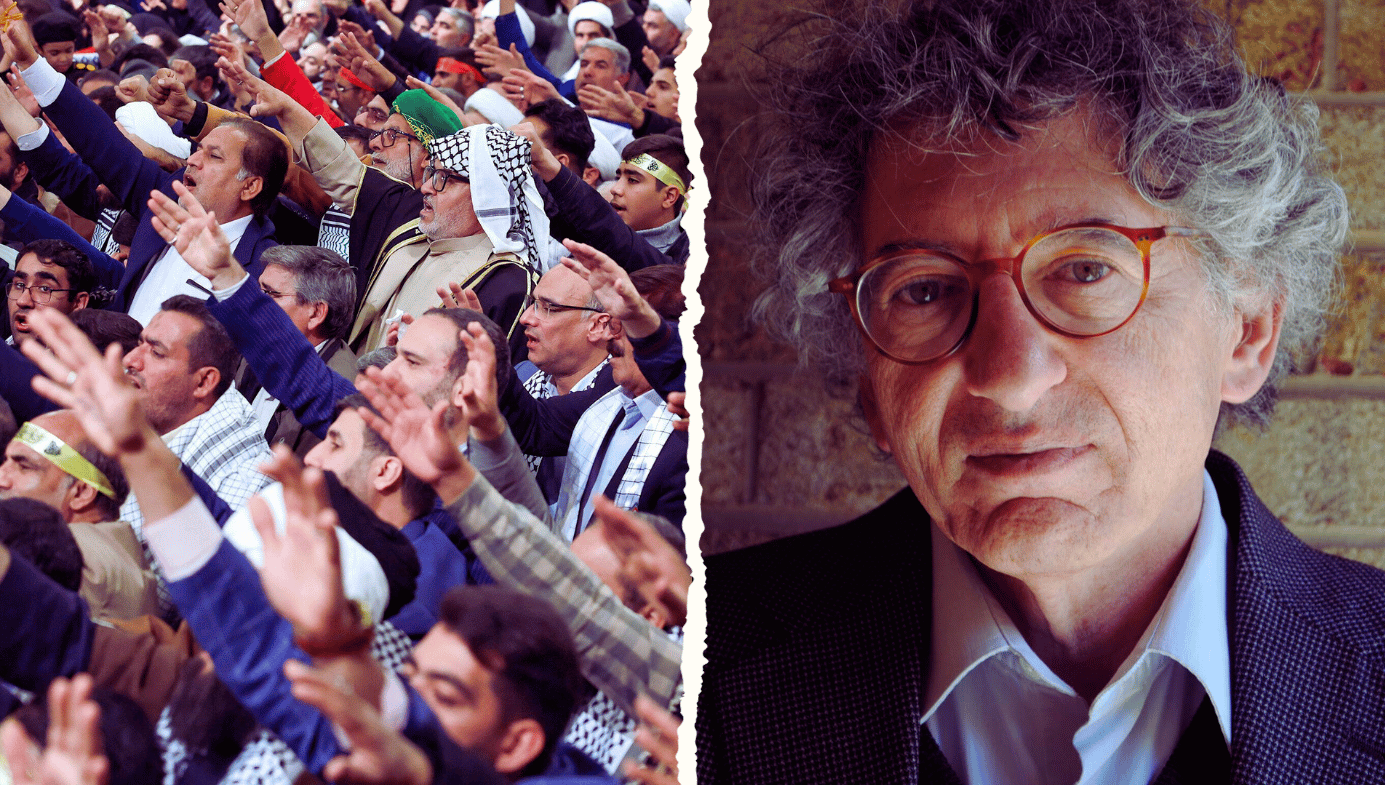

On 10 May, US historian Jeffrey Herf spoke at a small café in Berlin established to discuss antisemitism and the Western Left’s growing hostility to the state of Israel.

In 2022, three German intellectuals and restaurateurs opened the Café Bajszel (pronounced by-zel) in the Neukölln section of Berlin. Alexander Carstiuc, Andrea Reinhard, and Alexander Renner’s project had a political purpose—namely, to create a public place where liberal supporters of Israel and critics of antisemitism could meet and hear talks by academics and intellectuals about these issues.

On 10 May, I gave a talk at Bajszel about Drei Gesichter des Antisemitismus, the German translation of my latest book, Three Faces of Antisemitism: Right, Left, and Islamist. My German publisher, Hentrich and Hentrich, has also recently published Matthias Küntzel’s work on Nazism and Islamic antisemitism and Benny Morris’s works on the war of 1948 and the Palestinian refugee problem.

Neukölln is a dangerous place for an establishment of this kind, since a significant number of Hamas supporters live and work in the area. Presentations at Bajszel are therefore a standing rebuke to the attacks on Jews and supporters of Israel that have become increasingly common in Germany, especially since 7 October 2023. Hamas supporters have defaced the café by pasting the terror organisation’s red triangle icon on its windows; staff and customers have been intimidated and called “child murderers”; the café’s walls have been vandalised with graffiti exhorting passers-by to “Free Palestine from the River to the Sea”; rocks have been hurled at its windows; and on one occasion, an arson attack was combined with an attempt to lock the doors, which could have killed everyone inside had it been successful.

On 29 April, Felix Klein, the German federal government official assigned to monitor and fight antisemitism, visited the café in a gesture of solidarity. “What I saw there,” he said in reference to the posters, stickers, and graffiti, “was truly outrageous. The anti-Israel-related antisemitism manifested on the walls of buildings is truly unbearable. ... Words quickly become actions, and this is precisely the hatred that Bajszel is experiencing here.”

Bajszel is now under the protection of Berlin’s police, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. When I spoke there, two police cars and a police van were stationed outside the café throughout the event, accompanied by about a dozen uniformed and plain-clothes officers. This was more security than I had seen at any intellectual event I have recently attended, but it ensured the talk and subsequent discussion were able to proceed without interruption.

What I found even more memorable than the size of police detail was the audience of eighty or ninety people on a Saturday evening in Berlin, most of whom were between the ages of twenty and fifty. When Alex Carstiuc finished his generous and well-informed introduction, the audience burst into applause before I began to speak. Many of the attendees were familiar with my scholarship and my political essays, including my writing for Quillette. I spoke for about 45 minutes about my book and about political developments in the United States. The question-and-answer session continued for another ninety minutes, followed by another round of appreciative applause.

I am not describing the evening at Bajszel to advertise my international renown, but because the event there revealed something important and heartening. Although Germany, like most European countries, has a noisy postcolonial Left that vilifies Israel, the café and its attendees are evidence of a liberal intellectual and political current still dedicated to defending the state of Israel, even when taking that position incurs a personal risk.

What follows is an abridged and lightly edited version of the remarks I delivered there on 10 May.

Good evening. I decided to gather a number of my essays into this volume to urge the reader to confront what I call an “era of simultaneity”—Ära der Gleichzeitigkeit—that is, one in which antisemitism has vocal advocates on the Right, on the Left, and among the Islamists at the same time. In that sense, the book is a scholarly manifesto against political and ideological polarisation and for a vigorous centrist liberalism of the kind that the Café Bajszel has supported since its founding. Scholarship about Nazism, the Holocaust, and the hard-right remains essential today, but it is not sufficient to address the Jew-hatred and hatred of Israel that has come from the radical Left and Islamists, particularly now that the leftist-Islamist front has been galvanised by the Hamas massacres of 7 October 2023.

I am not here this evening to talk about the details of those attacks, nor about Israel’s subsequent wars against Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Those events have been exhaustively documented in the 7 October British Parliamentary Commission Report chaired by Lord Andrew Roberts. As a historian, however, I would like to speak about why this war took place and how it might have been prevented.

It is my view that if more governments around the world had denounced the ideology of Hamas earlier, exposed its tunnel construction, and demanded an end to the funding it received from Iran and Qatar, and if the major newspapers and media—not to mention the United Nations, famous for its numerous resolutions denouncing Israel—had kept up a drumbeat of critical reporting on Hamas, perhaps the Islamist terrorists’ hold on Gaza would have been weakened. Under these circumstances, the 7 October massacre might not have happened and the tens of thousands of people who have died since would be alive today.

In years to come, historians will have time to assess the long-term and short-term causes of this war. In the meantime, the essays collected in Drei Gesichter des Antisemitismus offer a partial explanation of the long-term causes and draw attention to ideas that unfortunately received far too little attention in the United States, Europe, and among Arab governments. My book contains eighteen essays, ten of which draw upon my historical scholarship on reactionary modernism, Nazi Germany’s antisemitic propaganda, East Germany’s “undeclared war” on Israel, and the attacks on Israel from the West German far-left of the 1970s.

This evening, however, I want to focus on the essays in which I brought a historian’s perspective to bear on events that occurred after the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington on 11 September 2001. These essays explore a puzzling question: why did Islamism, which is a profoundly reactionary phenomenon, become a cause célèbre of a significant part of the global Left? Why has it largely escaped denunciation in the United Nations, and on Western campuses, among students and senior faculty alike? Where, in other words, is the spirit of anti-fascism when faced with a movement that repeated the kind of Männerphantasien and raw Jew-hatred that has not been seen in world politics since the Nazis?

In their respective works on communism, nationalism, and jihadism in the Middle East, Walter Laqueur and Laurent Murawiec examine the long history of the strange alliance between communists and Islamists that began in the era of Lenin and the early years of the Comintern and continued periodically with the communist parties in the Middle East. Condemnation of the Zionist project and then Israel as a form of colonialism was not original to the “postcolonial” writers of the 1980s. It had long roots in the communist and leftist movements of the twentieth century.

Less well known is that the Nazis’ antagonism to Zionism was inseparable from their hatred of the Jews. Contrary to Soviet propaganda, the Nazis were fervent opponents of the establishment of a Jewish state in British Mandate Palestine. In postwar Germany, given the association between anti-Zionism and Nazism, only the Soviet Union, East Germany, and the West German radical Left could offer intellectual and political respectability to anti-Zionism, something that the Islamists with their Nazi collaborationist history could not offer. This intellectual and political respectability in the secular leftist world and at the United Nations took the form of the communist anti-fascism and third-world radical nationalism that fed the anti-Zionist passion.

In Germany, it was the secular Left of the 1960s and ’70s—both within the Soviet bloc and across the global radical Left—that made hatred of Israel an intellectual and morally respectable form of antifascism and anti-racism. This paved the way for the linguistic magic of recent decades that transformed a reactionary phenomenon like Hamas into a cause of the global Left. The distortion of political language allowed the reactionaries of Hamas to be redescribed as heroic revolutionaries and “resistance” fighters, and Israel’s parliamentary democracy to be compared to totalitarian Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa.

As Bassam Tibi points out in his book Islamism and Islam, Islamists also responded to criticism of their ideology with the invented concept of “Islamophobia,” which turned liberal hostility to their totalitarian doctrines into a bigoted attack on Muslims and their faith. This turned out to be an effective political counteroffensive. Many liberal intellectuals refrained from writing clearly about Hamas, its origins, and its goals for fear of appearing intolerant, “Eurocentric,” or even racist.

The upshot was what I call a “second era of underestimation”—a disturbing lack of interest in public discussion of the texts of Islamism. My book includes an essay I wrote in 2014 titled “Why They Fight: Hamas’s Little Known Fascist Charter,” in which I sought to bring the salient points of Hamas’s foundational covenant to the attention of a wider English-language readership. That document is as important to understanding contemporary antisemitism as Hitler’s prophecy speech on 30 January 1939 was to understanding the implementation of the Holocaust. It is an essential part of the central historical context of the Hamas attack of 7 October 2023—the ninety-year Islamist war of religion that first sought to prevent the formation of the state of Israel and then sought to destroy it.

The text of Hamas’s Charter expresses a profound religious hatred of Judaism, the Jews, and Israel. It blames the Jews for the French Revolution, World War I, and World War II, and it repeats the conspiracy theories of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. It is one of the most important reactionary texts of the last forty years, and it betrays clear evidence of the influence of the Nazi propaganda transmitted across the Arab and Muslim world during World War II. However, with only a few exceptions, the Western liberal commentariat and political class has been extremely reluctant to acknowledge this document or its meaning, and some parts of the Left have engaged in an absurd effort to present it as some sort of progressive manifesto.

In another essay, titled “From the River to the Sea,” written in November 2023, I examine the Hamas statement of 2017, a strikingly successful effort to recast Hamas’s religious war in the language of secular, anti-colonial leftism. Despite the more secular tone and the excision of references to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the intention to reclaim “Palestine” from what is now the whole of Israel remains clear. That now-famous phrase “from the river to the sea” comes from a revised—and supposedly more moderate—text of the Charter published in 2017.

There are many reasons why a large number of citizens in my country and in this one have turned to the hard-right. The Left’s indulgent treatment of Islamism is only one of those reasons, and for many voters, it is not the most important one. Nevertheless, one of the implications of the essays in this volume is that more frank and honest criticism of Islamism by liberal and social-democratic leaders might have blunted the rise of the far-right and its anger at establishment institutions. A frank discussion by liberals on both sides of the Atlantic is just one aspect of the kind of defence needed to protect our democracies against the threat posed to them by Donald Trump in the US and the Alternative for Germany party here.

Trump has dispensed with the distinction between Islam and Islamism entirely (if he ever understood it in the first place), bringing the same damaging obfuscation into mainstream public discourse that was created by academics, political leaders, and journalists after 11 September. Beginning in the late 1990s, the German government’s annual reports of the Verfassungsschutz (Office for the Protection of the Constitution) were a welcome exception to this pattern as its officials began to make clear distinctions between Islam and Islamism and discuss the link between Islamism and antisemitism.

In the United States, writing clearly and plainly about leftwing antisemitism has become more difficult in the context of the Trump administration’s reactionary assault on the universities. Drei Gesichter des Antisemitismus includes several essays that examine the similarities and differences between Trump and fascism and Nazism, and the disastrous implications of an “America-First” foreign policy. These implications are now evident in Trump’s attacks on the Western alliance and on the victim rather than the perpetrator of aggression in Ukraine. They are evident in the assaults on modern science and medicine in our universities, and in Trump’s unconstitutional declarations of various emergencies to deprive immigrants of the due-process rights established in the United States in the 1930s.

In the near term, the prospects for change in the universities are not promising. The anti-Zionist mood in much of the humanities and social sciences will be with us for some time now. Introducing greater viewpoint pluralism into departments captured by that mood should be a priority of leaders of universities in Europe and the United States. Drei Gesichter des Antisemitismus is a collection that will, I hope, foster the movement of perspectives that are finding expression here at Bajszel into the mainstream of German and European universities, media, and politics.

The “global intifada” that has led to attacks on this venue, and now to the murders of Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim in Washington, DC, is assuming ever more violent forms. Café Bajszel is that small part of the public realm extolled so enthusiastically by historians of the European coffee house. In this case, it is bravely playing an important and distinctive role in defending liberal democracy and fighting the scourge of antisemitism and antagonism to Israel.

My thanks for your good questions, spirited discussion, and warm reception. It was an honour and a pleasure to speak here on this Saturday night in Berlin.

Sol Stern’s Quillette review of Three Faces of Antisemitism by Jeffrey Herf can be read here: