Israel

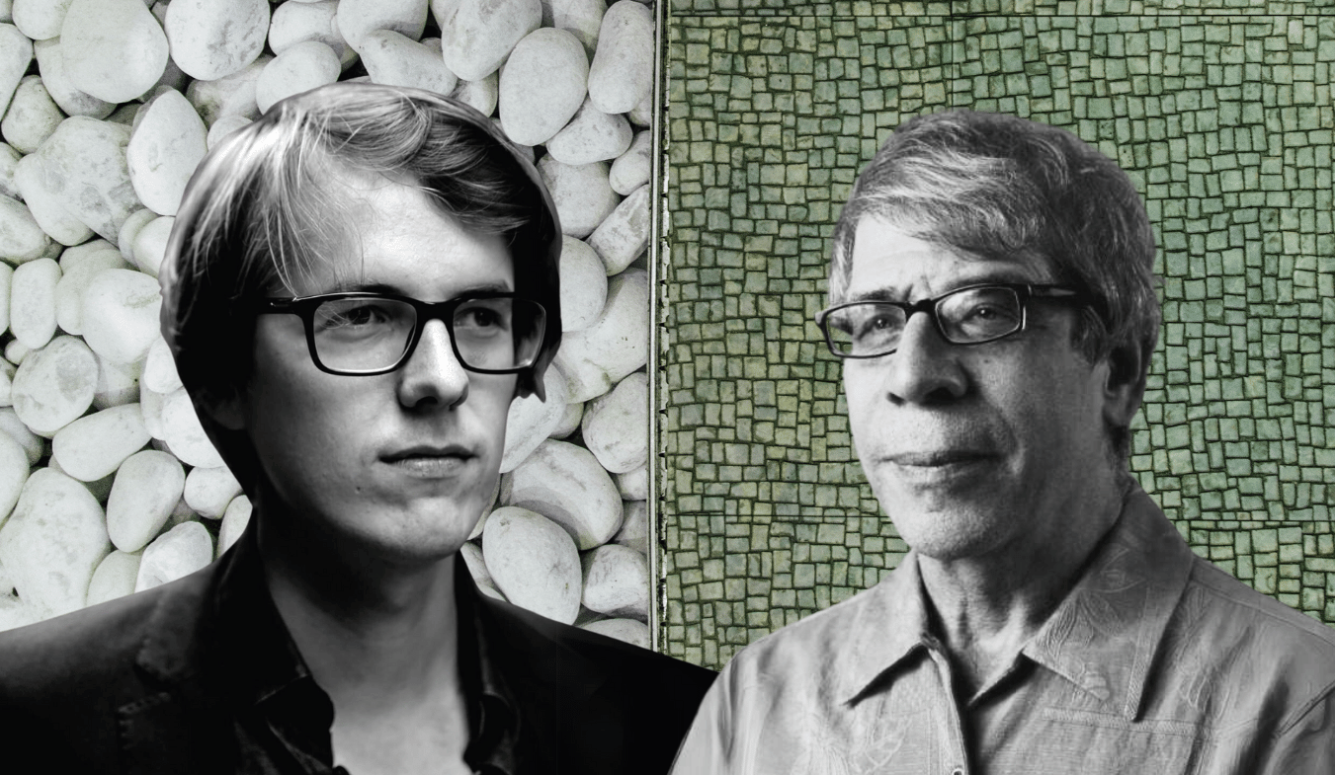

The Biggest Taboo in Academia: Israel, with Maarten Boudry | Quillette Cetera Ep. 46

"That was the moment I realised I had underestimated the ideological rot inside academia."

Zoe Booth: Maarten, thank you so much for joining me today. I know it’s very early for you and you woke up early just for me, so I really appreciate it.

MB: Glad to be here.

ZB: I’ve read so much of your work. We’ve published a number of your pieces on so many different topics, from underpopulation to climate change. Recently, however, you’ve been writing a lot about Israel, and I know that you recently went to Israel, and I read your account of your time there.

MB: That’s right.

ZB: I wanted to know—have you always been interested in Israel, or is it a new interest?

MB: It’s a relatively new interest, to be honest. I can actually date this very precisely—on the 8th of October 2023. So not the day of the Hamas massacre, on the 7th of October, which of course I was aware of, but it didn’t really surprise me, because Hamas is a jihadist death cult, in many ways similar to other jihadi organisations like ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Jabhat al-Nusra.

But then the day after—or perhaps even the day itself—I started to become aware of some of the reactions from leftist friends, mostly academic colleagues at the university. I was completely blown away by that. It really caught me off guard.

Before that, I don’t think I had a strong interest in Israel. I had a very steep learning curve. I’ve been reading up on the history of Israel ever since the 7th of October because I wanted to understand where this was coming from. And with “this,” I mean the obfuscation, the apologetics, and sometimes the outright glorification of the Hamas terrorist attacks.

I was aware of this ideology of decolonisation or postcolonialism for a number of years, but I underestimated it or didn’t take it very seriously. I’d heard some rumours, for example, in my department—the philosophy department in Ghent—about decolonising the curriculum because there are too many white males, dead white males, in the curriculum. Fine. I just roll my eyes. I’m not even against that per se—I’m for diversity—but I didn’t take the ideology seriously. I also thought nothing much was at stake when it came to changing the curriculum.

But when it comes to terrorist attacks and existential threats to liberal democracy, something is really at stake. That’s when I decided—OK, I need to understand this ideology. And that’s when I started writing about Israel, because no one else was. I mean, if you think it’s bad in Australia or the US, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Europe—and specifically Belgium—I’ve never encountered anything like this before. I’ve written, as you say, about a lot of controversial topics. Nuclear energy is controversial. Population is controversial. But I’m literally losing friends over this.

The subtle vision in Belgian media and academia, I would say, is even stronger than in the Netherlands, and definitely compared to the US. So that’s when I started writing about Israel—because I still see Israel as a liberal democracy, and I don’t understand why people—well, I do now—treat Israel as the aggressor, as the country that should shoulder all the responsibility and guilt for what happened on the 7th of October and afterwards.

ZB: Yes, it’s very strange, isn’t it? How people have such high standards for Israel, and there’s such a focus on the Jewish state compared to the myriad of other countries and conflicts in the world. I, too, am just baffled—I don’t get it. And since 7 October, I’ve had a similar experience. I’ve had to learn more because it didn’t make sense to me. And yes, it’s been so much learning. And I, too, have lost a lot of friends.

Would you say that this has been the most controversial topic that you’ve broached? The most taboo?

MB: Oh yes, by a long stretch. I mean, I’ve written about Islam before. For example, I did read the Hamas Charter—I think before 7 October—because I’ve always been interested in Islamic fundamentalism.

My academic research started with pseudoscience—the difference between science and pseudoscience—but then I expanded that into irrational belief systems in general. In that context, I became interested in death cults, religious fundamentalism, jihadism, etc. I’ve written about that, which is, in its own right, controversial. I think I interviewed an ex-Muslim, Ali Rizvi, for Quillette as well. And in the Dutch and Belgian media—because ex-Muslims are a minority within a minority—they’re oppressed in many ways and didn’t really have a voice. So I wrote about that.

That was controversial, but it pales in comparison to what I’ve experienced after 7 October. I don’t think I lost any friends over what I wrote about ex-Muslims. It was controversial—some people said I was legitimising right-wing discourse or that I was a sell-out—but this is something else.

If I’m being charitable, I do understand—thousands of people are dying. Of course, we shouldn’t trust the Hamas figures, but even conservatively, there are thousands of innocents—children, by definition, are innocent. So I understand that emotions are running very high.

And I’m going to be even more charitable. I do think I understand, at least partly, why so much attention is focused on Israel, even among people who are not indoctrinated in postcolonial ideology. Because unlike many other conflicts in the world, Israel is still a major Western ally. It’s allied with the US, but also has a special status in Europe through the Association Agreement. It participates in the Eurovision Song Contest, etc.

MB: So I understand. I’m even willing to accept that we should hold Israel to a higher standard. I mean, it’s pointless to try to put moral pressure on Hamas—they couldn’t care less about international humanitarian law. They’re a jihadist death cult. But Israel is a liberal democracy—or pretends to be—so that’s why we should hold it to a higher standard.

But even so, the criticism is so extreme. I’m not even pro-Netanyahu—I think he’s probably one of the worst prime ministers Israel has had. Everything would be much better with someone else in charge—not even talking about the far-right goons in his coalition.

But still, I could defend the US against its enemies despite Trump. I’m also not a fan of Trump, but in spite of Trump, the US remains a liberal democracy—and so does Israel. That’s mostly what I was writing about in my piece. It wasn’t so much about the war itself, which is horrific—I hope it ends as soon as possible—but more about Israeli society.

I think Europeans—perhaps more than Americans—need to understand that Israel is not an apartheid state, at least not within the Green Line, on internationally recognised territories. Arabs and Muslims have full civil rights, they can run for office, they hold high positions in civil society. They sit on the Supreme Court. They’re doctors, lawyers.

To some extent—and this is something I learned on my Israel trip—I think Israel is doing a better job at integrating its Muslim Arab community than Europe does. There was a gay Muslim influencer—an Arab Israeli—who told me not just that he was glad to be in Israel rather than other Arab countries—obviously, no gay pride in most Arab countries, perhaps Lebanon being the sole exception—but he was even glad to be in Israel compared to Europe.

And I thought about that. He’s right. I can’t think off the top of my head of an openly visible gay Muslim influencer in Belgium—or even in the Netherlands. This guy was a household name—he’d been on the local version of Big Brother, everyone knows his face.

MB: I can’t imagine that happening in Belgium. There was a female imam in Germany who made inclusive comments about gay people and allowed them in her mosque. She received so many death threats that she required round-the-clock protection.

So in those respects, not only are people failing to appreciate that Israel is a liberal democracy—not an apartheid state—but these European countries, which are quick to condemn Israel for apartheid or Jewish supremacy, could actually learn something from Israel.

ZB: Not to be too cynical, but—how much of this do you think is about Israelis being Jews?

MB: Much of it—but perhaps not in the straightforward, direct sense that you might imagine. This is something I’ve discussed with some of my Jewish friends who, of course, have far more experience with antisemitism than I do. So I’ve listened to their stories and experiences.

Obviously, it makes a huge difference that Israel is the only Jewish state in the world. But when it comes to some of my leftist friends—academic colleagues—I wouldn’t accuse them of antisemitism per se, or at least I don’t think that’s the major factor that turns them against Israel.

I think antisemitism plays an indirect role in this sense: the really vicious antisemitism is mainly to be found in Muslim communities. Obviously, Hamas is an extremely antisemitic organisation. Its charter literally quotes that infamous hadith verse about stones calling out to Muslims to kill Jews hiding behind them—an exterminationist ideology.

So is Hezbollah, so are the Houthis, so are large parts of the Arab world. That’s pure antisemitism.

In academia, antisemitism plays an indirect role. The leftists are the useful idiots and apologists for the real antisemites—Hamas and these other enemies of Israel. They’re not so much antisemitic themselves, but they don’t understand the ideology of the people attacking Israel. Their main ideological lens is this binary between victims and oppressors—with Western civilisation as the biggest culprit.

MB: That’s what I also wrote in my piece. Israel is a proxy of the West—by implication, it’s complicit in all the West’s alleged sins: colonialism, racism, apartheid, etc.

And because they divide the world into pure, innocent victims on one hand, and evil perpetrators on the other, they will always excuse horrific actions by groups they see as victims. So, even if they acknowledge that what happened on 7 October was horrible—war crimes, perhaps even genocidal—they will always rationalise it as a reaction to decades of oppression.

At my university, leftists are just not interested in the ideology of Hamas. They only want to portray Palestinians as innocent victims passively reacting to what’s been done to them—as if they have no agency, no moral autonomy, and no ideological or religious traditions of their own.

That, I think, is the indirect role antisemitism plays—at least in academia. But if you go into Muslim communities—look at what happened in Amsterdam a couple of months ago. After a football match involving Maccabi Tel Aviv, there was, literally, a Jew hunt. This wasn’t about Zionists or being anti-Israel. It was, very explicitly, a call to hunt Jews. That’s real antisemitism.

MB: And then, of course, you have the left-wing apologists who immediately start downplaying it: “It’s not really about Jews,” or “They’re just frustrated,” or “That was an isolated incident.” Or they say it’s really about concern for children in Gaza.

So that, I think, is how antisemitism plays out at university. I wouldn’t accuse most of my friends of antisemitism—but I do think they are useful idiots for the real antisemites.

ZB: Hmm. That leads me to a broader question—about liberalism. Europe in particular—we hear so many stories about tensions between native Europeans—whether they’re French, German, Dutch, Belgian—and migrants, often young men from different cultures.

Europeans have liberal values, but many of these young men don’t. They’re often not tolerant of Jews, or women wearing what they like, or gay rights. So, how do we manage that? How do we remain liberal while dealing with people who are not liberal?

MB: Yes, that’s been a long-running debate in Europe. And this is something I’ve been writing about for quite a while—not about Israel specifically, but I’ve built up a reputation here in Belgium and the Netherlands—sometimes I’ve translated pieces for Quillette—for being politically incorrect about migration.

As you put it, there is a real problem in Muslim communities. Not with all Muslims, obviously—some of my friends here in Ghent are Muslim—but it is true: not just regarding antisemitism, but also deeply conservative—or more accurately, reactionary—views about women and homophobia. Or let’s call it what it is: hatred of gay people.

These attitudes are much more prevalent in Muslim communities compared to the native population. And you see this across all European countries. It’s not caused by any one national model. It happens in Sweden, the UK, France—everywhere.

MB: As an academic, it’s extremely difficult to talk about these issues without being accused of giving ammunition to the far right. That’s what drives me mad—this idea that simply talking about these problems will mainstream far-right parties.

But anyone with common sense can see it’s the opposite. If you stay silent about it, ignore people’s concerns, that’s what drives them into the arms of far-right parties.

A couple of months ago, I did a study visit in Berlin with a sociologist [Prof Ruud Koopmans] who’s been blackballed and ostracised at his own university. He’s one of the last remaining academics in sociology or the humanities who dares to study these issues.

He’s published influential papers comparing homophobia, antisemitism, and reactionary views about women in Muslim and non-Muslim communities. And the results are clear. But when he published this around 2015, it caused a huge uproar. The media said it was grist for the far right. “How dare you stigmatise these communities?”

MB: I think for a very long time, European politicians have either been blind to this issue or, if not blind, simply refused to speak out for fear of offending left-liberal sensibilities—or those of the Muslim communities themselves.

Things have improved slightly in recent years. Anti-immigration parties are on the rise everywhere. Some of them are, of course, very distasteful. Alternative für Deutschland is one of the most infamous examples—these really are far-right parties with roots in blood-and-soil ideology. I don’t use the word ‘fascist’ lightly, but in some cases it may apply.

What’s happening now across Europe is that mainstream parties—centre-right and even centre-left—are finally realising they have to offer an alternative. If they keep ignoring the issue, some far-right party is eventually going to seize power. Whether it’s Marine Le Pen in France or AfD in Germany, that’s the risk.

Now you see figures like Keir Starmer in the UK or even Geert Wilders in the Netherlands—although Wilders is a special case. I should clarify, he’s Dutch, not Belgian.

ZB: Geert Wilders—he’s Dutch, isn’t he? Not Belgian?

MB: Yes, Dutch. He’s now part of the coalition in the Netherlands, although he’s not the prime minister. He leads one of the far-right parties.

But I’m talking more about the centre-right parties that are shifting their positions. They’re now advocating stricter border control because they realise it’s what the population wants. And luckily, democracies can still course-correct—if they receive strong, persistent signals from the electorate.

Of course, some of my left-wing friends are dismayed. They think figures like Starmer and Macron are starting to sound like the far right because they’re problematising immigration. But I think that’s exactly what’s necessary. If you want to prevent far-right parties from gaining power, mainstream politicians need to take the issue seriously.

Even using the word “flood” to describe migration is controversial—it’s accused of being dehumanising. But I’m using it as a statistical metaphor. I’m not dehumanising anyone.

We have to control the flow of migration. Liberal democracies can absorb a certain percentage of illiberal individuals—people who spit on our freedoms. But that capacity is not infinite.

And in some places, we’re already seeing the limits. In certain neighbourhoods of Brussels, Amsterdam—you’re still technically in a liberal democracy, but you can’t walk hand-in-hand as a gay couple. You can’t wear a miniskirt without being harassed or catcalled, or worse.

MB: This is only happening in certain cities, and of course, there’s a lot of segregation in European urban areas. I do think we’ll eventually overcome these problems. It’ll take years—decades even. But I also see hopeful signs.

Parts of the Muslim community are turning away from religious fundamentalism. Many are doing it quietly—they don’t want to upset their families or communities. Some women are taking off the veil. Others still wear it but are liberalising in other ways. They’re moving away from religion.

But if we want to solve this problem, we at least need proper border enforcement. Because if you continue allowing millions more to enter from countries with these cultural values, then I wouldn’t say Europe is doomed now—but it would be doomed if we opened our borders completely.

And I know that’s a difficult message. But it’s unavoidable. The current situation simply cannot persist. We have to act.

ZB: And Australia is lucky in the sense that we’re an island. We don’t share land borders, so things are more manageable here. But I’ve been to Europe many times, and I’ve seen small towns change. I visited Calais last year—that was really eye-opening. I stayed in a hotel that was almost empty—no one there except the gendarmerie, with their big guns—they were just patrolling. It didn’t feel like France. It was very strange.

But I want to circle back to the topic of ideological capture at universities. What can be done? There’s a lot of talk about saving universities, but in practical terms—what do you think could actually improve freedom of speech on campus—for academics and for students?

MB: Yes, that’s extremely difficult. I must say—even though I’m generally an optimist, someone who believes in progress—on dark days, I’ve given up on universities. Not all of them, of course. Some colleagues are still doing good work.

But in Ghent, for example—to my shock and disappointment—the university imposed a boycott on Israeli universities. They don’t want to call it a boycott, but that’s effectively what it is. They’ve severed all institutional ties.

I was really surprised, because I actually know our rector personally. And I thought he was going to hold the line. After 7 October, there were immediate calls for a boycott. Initially, he said, “No—we’re not going to punish universities for the actions of their governments. Many of these academics are critical of Netanyahu.”

And I thought, good—he’s resisting. But eventually he caved to the months-long protests, occupations, the faculty petitions, and reports from the university’s own human rights commission. Now the boycott is decided—it’s not yet implemented, because many collaborations are part of EU-wide projects like Horizon. But the direction is clear.

What can be done? At my university, honestly, it would take hell freezing over for this boycott to be reversed. We have a new rector now, and from my perspective, she’s even worse. She used to be Belgium’s deputy prime minister—she’s from a green left-wing party, and she’s even more anti-Israel than her predecessor.

So yes, I think that battle has been lost—at least at my university.

ZB: And I know you wrote about it for us—that you and Jerry Coyne were disinvited from giving talks at the University of Amsterdam. I’m sure you’ve faced other consequences too—not even for being some kind of rabid Zionist, but simply for not hating Israel. It seems like the only acceptable opinion is to completely hate Israel. It’s crazy.

MB: There was an interview in the newspaper with a philosopher who was asked about my views on Israel—specifically, what he thought of my claim that Israel is fighting a just or justified war. He said he’d rather suspend judgement.

Even that is no longer acceptable. You have to condemn Israel. You have to use the G-word—you have to say “genocide.” Anything less than that is seen as unacceptable.

Regarding Amsterdam, yes, it really was Orwellian. I’ve never experienced anything like this before. Not even when writing about Islam, migration, or nuclear energy. This was something else entirely.

But actually, I have an interesting update. So, as you mentioned, I was deplatformed twice at the University of Amsterdam. Once on my own, which was a bit ambiguous—they cancelled due to protests and the university said they couldn’t guarantee security, which I understand. But the second time, I was deplatformed together with Jerry Coyne—who’s pro-Israel and Jewish himself.

Once the organisers became aware of our views, they retracted the invitation—just two days before the scheduled event.

And what’s interesting is the reason they gave. I don’t even think those particular students were especially anti-Zionist or narrow-minded. But they were afraid—afraid of retaliation from other student groups who might ostracise them or damage their reputations. That fear is incredibly powerful.

MB: So what you’re seeing is a dynamic in which probably a vocal, aggressive minority has managed to impose its ideology on everyone else. There’s so much preference falsification going on. I’ve had colleagues tell me privately—in emails or in whispered conversations—that they actually agree with me, that they think this demonisation of Israel is completely wrong. But they won’t say it out loud because they’re afraid of the backlash.

So yes, we were deplatformed. But then, a few months later, I received another invitation from a different student group at the same university. This time, I didn’t warn them in advance. I thought, let’s just try a little experiment—say nothing and see what happens.

And nothing happened. No protest. No cancellation. I went, gave the talk—it all went smoothly.

I’m not sure if that’s a hopeful sign. Maybe it just shows that if you don’t wake the sleeping dogs—if you don’t announce your position—it can go unnoticed. The first time, we warned the organisers. We told them, “Just a heads-up: our views on Israel have caused issues before. If you think extra security is needed, please make arrangements.”

But in doing that, we probably triggered the whole thing. So the third time, I didn’t say a word, and there were no problems.

I think there’s a silent majority in universities—students who don’t support the pro-Palestinian fringe—but they don’t want to fight that battle. They don’t want the social cost. And I understand that. But the consequence is that it looks like the whole university has been ideologically captured.

ZB: Yes. At least in Australia, it feels like the heat has died down a little. In my area, which is very Jewish, there were a lot of attacks after 7 October. A house behind mine—previously the home of a Jewish community leader– had red paint thrown on it and a car was firebombed. Synagogues were targeted, torched.

But recently, it’s come out that it wasn’t necessarily random individuals. It looks more like organised crime. There are theories about Iranian funding, or involvement from the bikie gangs. There’s still more to learn about it.

But all that to say—the tension has dropped. And it’s a welcome reprieve.

And even looking at our content at Quillette—the videos, the articles—interest in Israel and antisemitism has waned. I wouldn’t say it’s less important, but it’s no longer as viral as before. People aren’t obsessing about it as much.

And honestly, I think that’s a good thing. Israelis and Jews just want to live normal lives—without constantly having to worry about who’s coming for them next.

MB: Yes, that’s very interesting. I don’t really have the impression that things are calming down here in Europe—certainly not at my university. Very recently, there was another occupation.

And of course, you can’t please these people. The university already agreed to boycott Israeli academic institutions. But because it hasn’t yet been fully implemented—due to legal complications with Horizon projects and such—they’re still not satisfied. They say the university is lying or being hypocritical.

I often wonder what will happen if the war ends—though I think it could be ended in five minutes, if Hamas just surrendered and released the hostages. It’s probably the only genocide, quote-unquote, that could be stopped immediately by the aggressors themselves surrendering.

But even if the war ends, will the hatred fade? Will the protests stop? I don’t know. Even before 7 October, it was incredibly difficult to talk about Islam or migration in academic settings.

So, I can’t predict what comes after this.

MB: But I do think it’ll be a long battle. Even if the protests against Israel die down, we still have a major problem with the leftward shift of universities. I didn’t properly answer your earlier question, but there’s substantial research—both in the US and in Europe—that shows while broader society is shifting to the right, especially on issues like migration, universities are moving in the opposite direction.

And the two trends are feeding off each other. The more society shifts to the right, the more universities see it as their duty to act as a counterbalance. They believe they must uphold moral clarity or defend human rights, as they define them.

I don’t know how to break that cycle. It’s very difficult. One thing that sometimes works—ironically—is leveraging their awareness of bias.

For example, our new rector at Ghent has a well-known left-wing background. She was the vice prime minister of Belgium for a green party. Her views on Israel and nuclear energy—she’s anti-nuclear as well—are public knowledge. Now that she’s rector, she’s supposed to be neutral and a defender of academic freedom.

So sometimes, people on the left will point to someone like me—saying, “See, it can’t be that bad. We’ve still got Maarten Boudry at this university.” Or Prof Dr Ruud Koopmans in Berlin, for instance. That’s their way of claiming they’re still ideologically diverse.

MB: And I’m not even right-wing, by the way. But because I challenge certain left-wing orthodoxies, I’m perceived that way. And in a strange way, that helps them. It’s like I become a kind of token heterodox voice.

They understand—at least some of them—that if everyone in a faculty thinks the same way, there’s a problem. They’re still a little sensitive to accusations of groupthink or ideological conformity.

There’s that smug line from Stephen Colbert—“Reality has a well-known liberal bias.” It’s arrogant, but also telling. They genuinely believe that investigating the world leads naturally to left-wing conclusions. But part of them acknowledges that some ideological diversity is a good thing.

ZB: I saw you’ve got an upcoming book: The Betrayal of the Enlightenment: How Progressives Lost Their Way and Can Find It Back. Amazing title. I’d love to get my hands on a copy. Is it in English?

MB: I haven’t translated the whole book into English yet, but I’m working on it. I don’t have a contract with an English-language publisher, but I’ve translated a few chapters.

One chapter on victim-oppressor binaries—I’ve condensed it into an essay that’s going to appear in a book edited by Lawrence Krauss called The War on Science. That should be out next month. I also have another essay coming out in Quillette about how the Enlightenment is producing its own gravediggers—the tendency of Western intellectuals to undermine the very freedoms they rely on.

That essay is also adapted from the book. So I’ve started with excerpts and essays, and hopefully, I’ll eventually translate the full thing.

It’s been published here in Belgium, but of course, I’m getting trashed by the left-wing media. It’s a polemical book. There’s a chapter on Israel, which acts as a kind of lightning rod in the current climate.

MB: To be honest, I wouldn’t have written this book without 7 October. Or it would have been a very different book.

Israel doesn’t even dominate the argument—it’s just one example among many. There’s a large chapter on environmentalism, for instance, and how anti-growth ideology has flipped from the right to the left over the past fifty years.

It used to be a conservative position—anti-growth, protect tradition, preserve nature. But in the 1970s, it was embraced by the left. So that chapter has nothing to do with Israel, but it’s part of the broader thesis: how so-called progressives have abandoned Enlightenment values.

ZB: That makes sense. And it just reminds me how insane it is to boycott Israeli academics—considering Israel is such a hub of science and innovation. Even if you don’t like the government, excluding those scientists is so anti-Enlightenment, so anti-science. It’s just madness. I had to say that.

MB: Absolutely.

And the irony is, if you look at some of the EU projects that Ghent is involved in—many of them are on the very topics these activists claim to care most about. Climate change, for example. They had two demands: the 1.5°C climate goal, and boycott of Israel.

But many of our collaborations with Israeli universities are on climate solutions—alternative proteins, sustainable agriculture, green technologies. And they’re destroying those partnerships—just to flaunt their virtue and take a “pure” moral stance.

ZB: Pure virtue signalling.

Yes. Final question—how did you come across Quillette?

MB: That’s a good question. I’m not entirely sure. It must have been many years ago—it just crept up on me. I think I first became aware of it in 2017. Could it be a decade ago? How long has Quillette existed?

ZB: Ten years now—it’s our tenth anniversary.

MB: Right. So I think my first piece for Quillette was in 2017 or 2018. Possibly I found it through Steven Pinker. I’ve followed his work closely, and I think he was one of the early contributors.

Then I wrote that interview with Ali Rizvi—the ex-Muslim author. He’s fantastic, by the way. His book is excellent.

ZB: Yes—published in 2018. That interview still gets traffic.

MB: Yes, I think I just kept seeing the name Quillette, over and over. At some point I thought, “This is interesting.” And I’ve been proud to write for you. I think Quillette has stayed consistent—especially since Trump’s re-election. Some other so-called heterodox outlets have revealed their true colours—they’ve jumped on the Trump bandwagon or remained silent about the dangers from the right.

If you’re a genuine liberal, you have to defend liberalism against threats from all directions. And I think Quillette has done that.

ZB: That’s a great note to end on. Maarten, thank you so much for joining me.

MB: Thanks for having me. Lovely to meet you.