Politics

The Strange Western Surrender

When dealing with the Chinese Communist Party, why does the West find it so difficult to learn the exhausting lessons of bitter experience?

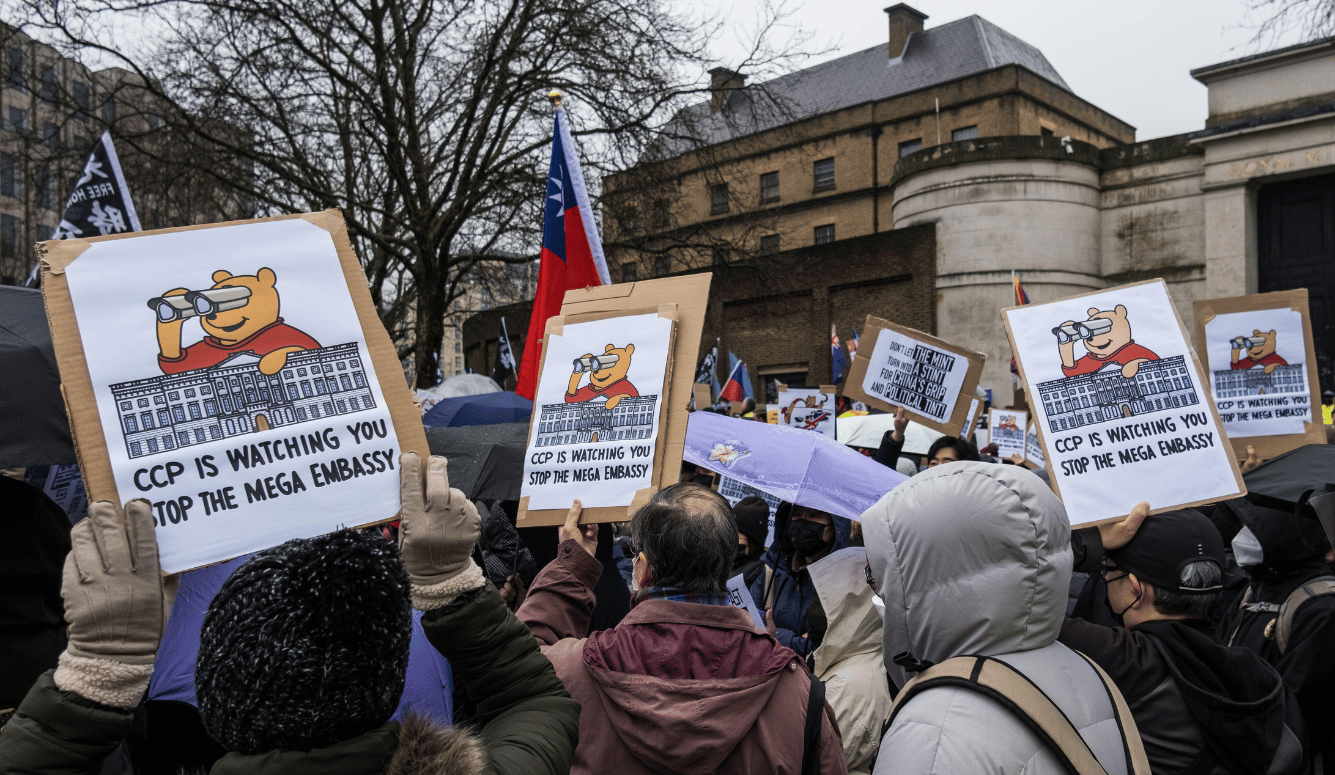

The mood was defiant as London’s anti-CCP coalition gathered at Royal Mint Court on Saturday 15 March, but there was also an unmistakeable tension. Protesters were meeting for a second time at the site of China’s planned super-embassy, and the demonstration was taking place in the most surreal, chaotic, and alarming of geopolitical contexts. The police vans that packed the surrounding streets drew uneasy glances—ostensibly a security measure, they also represent the executive arm of a state that may no longer be friendly to the opponents of totalitarianism.

What government can now be trusted? For Hongkongers, the United Kingdom has long served as both refuge and inspiration. On Saturday, I saw protesters proudly waving the old colonial flag, the “Dragon and Lion.” Lately, however, their sanctuary is looking unsafe. In return for a paltry £600 million in agreements over the next five years, the UK government has green-lit the construction of a giant Chinese embassy: an explicit statement of CCP power in the heart of London’s financial district. For all the rage and the 4,000-strong protests, there is no indication that Whitehall intends to rethink its position.

China’s mission will include a large basement complete with security airlock, as well as two suites of additional unlabelled basement rooms and a tunnel (this information was provided to the planning inquiry by Oliver Ulmer, director of David Chipperfield Architects, before being “redacted for security reasons”). That subterranean zone will almost certainly be used for intelligence work, but there is another, darker prospect: the kidnap and torture of anti-CCP dissidents. Two years ago, a Hong Kong protester was dragged into the Chinese consulate in Manchester and beaten by staff members. In the coming years, a more confident CCP may go much further than this.