Art and Culture

Rumble on the Royal Mile

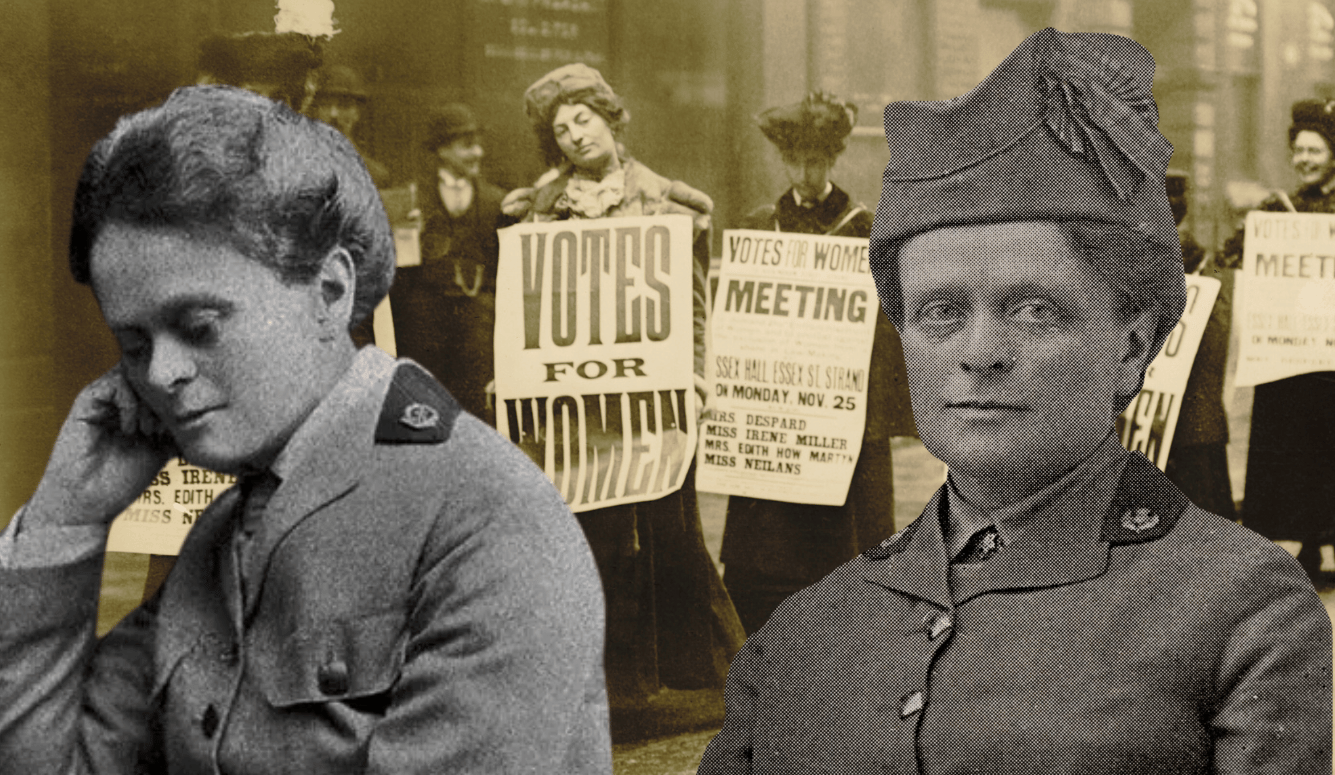

Scottish feminists are angry that an accomplished male sculptor has been commissioned to make a statue of a suffragette.

The latest battle in our inane culture wars broke out in Edinburgh this month when hundreds of concerned citizens signed an open letter objecting to a planned statue of suffragette Elsie Inglis on Royal Mile. But the row is not about the statue’s subject, it is about whether or not a male sculptor could possibly do her likeness justice. To add to the absurdity, the artist in question is Alexander Stoddart, one of the world’s most accomplished realists and certainly Scotland’s best sculptor.

Over the last decade or so, statues of suffragettes have been sprouting like mushrooms across the UK. In 2018, one appeared in Parliament Square and two were erected in Manchester. Last year, another popped up in the Welsh city of Newport, and two joined Queen Victoria outside Belfast city hall. Across the Atlantic, a large statue of a suffragette will soon appear on the National Mall in Washington, DC. If anything, Edinburgh is late to the game.

Dr Inglis (1864–1917) certainly deserves to be honoured. Besides campaigning for female suffrage, she saved the lives of poor mothers in Edinburgh and injured soldiers in WWI. But commissioning public sculpture is fraught with risk because vandalism has now become respectable. A charity called A Statue for Elsie Inglis started out well, raising more than £50,000 for the monument. But they rather bungled the selection process. First, they announced an open call in early 2022, then they called it off a few months later and announced that the job would go to Alexander “Sandy” Stoddart. This kind of dithering is hardly unprecedented, but it vexed other artists preparing pitches.

Even so, Stoddart ought to have been an uncontroversial choice. The King’s Sculptor in Ordinary, his magnificent statues of Scottish Enlightenment philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith stand nearby. Stoddart wins commissions like Ronaldo scores goals but it transpired that this illustrious track record was part of the problem.