Art and Culture

Hamilton and the Left

Consigned to the political wilderness, progressives and left-liberals could do a lot worse than shed their disdain for patriotism.

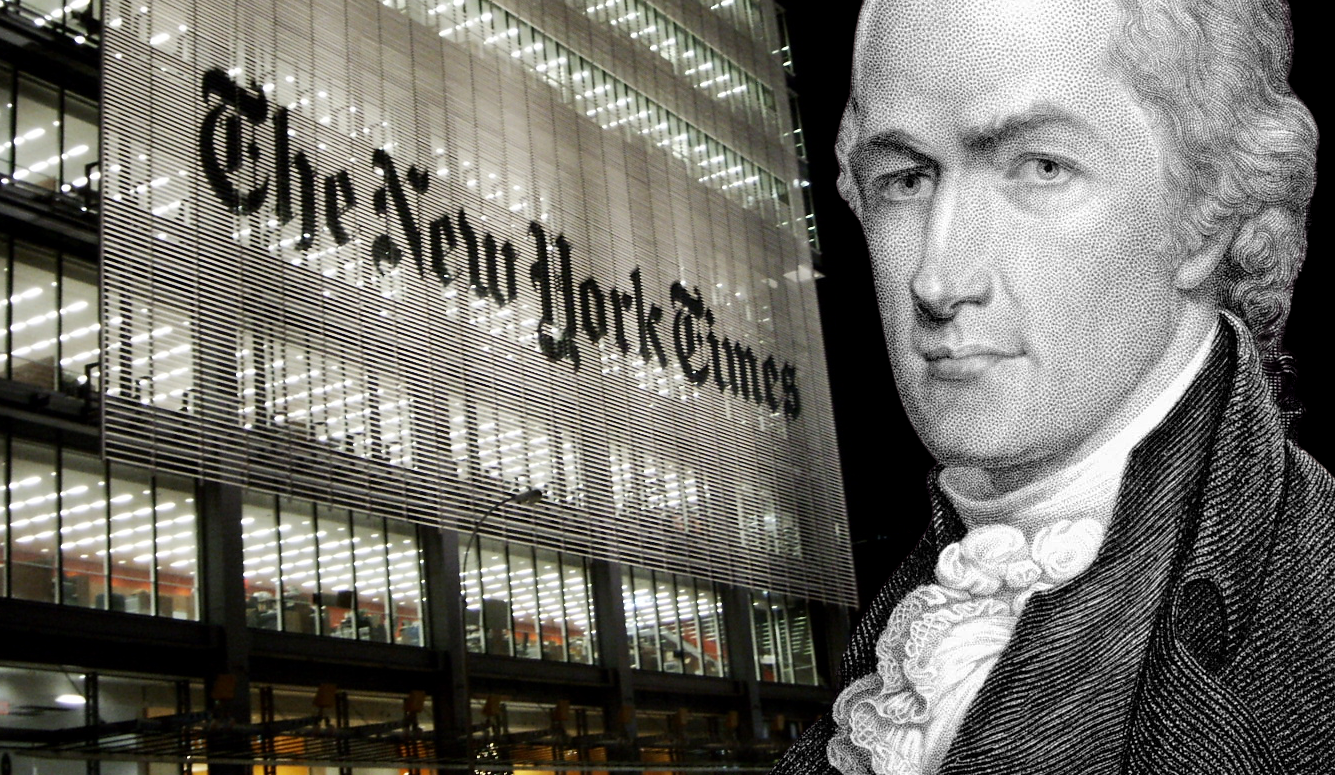

Anyone wanting to take the pulse of progressive America can consult the opinion pages of the New York Times. That’s where, earlier this year, I found Ezekiel Kweku, one of the paper’s editors, complaining bitterly about Hamilton. A decade after the musical about America’s neglected founding father became a Broadway sensation, Kweku wants his readers to know that it has not aged well. Kweku’s critique repays attention, not only for its revisionist interpretation of a popular piece of political art, but also because it crystallises the dilemma facing the political Left in the (second) age of Trump. Kweku’s polemic is emblematic of the unease—if not outright resentment—with which the Left regards American patriotism. And until it outgrows that defect and embraces national solidarity and pride, the Democratic Party will continue to flail in the political wilderness.

Hamilton is a cultural artefact of the Obama years. In 2008, Barack Obama’s meteoric ascent to the presidency was attended by a groundswell of exuberant national optimism about the world and America’s place in it. If the son of an African father could be elected to the nation’s highest office, who could still gainsay the promise of 1776? And it was from this buoyant atmosphere that Hamilton emerged. Its language and themes were unambiguously liberal, which was typical enough of show business, but it was also unapologetically patriotic, which was decidedly atypical. As such, casting a backward glance at the musical—Kweku recently watched it for the first time in San Francisco—reveals as much about Obama-era liberalism as it does about the founding of the republic.

With Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda told America’s origin story through the experience of the country’s most brilliant founding father. Born in the West Indies, Alexander Hamilton’s life was a marvel of self-creation, the chief consequence of which was the invention of a new kind of nation. After making his way from a flyspeck island in the Caribbean to the Thirteen Colonies, Hamilton enlisted in the Continental Army where he served as General Washington’s adjutant. After the War of Independence, he brought his considerable political wisdom to bear as a chief architect and advocate of the Constitution. Hamilton’s career culminated as a member of President Washington’s cabinet, where his liberal nationalism helped galvanise the dynamism and opportunity that have distinguished American society ever since.