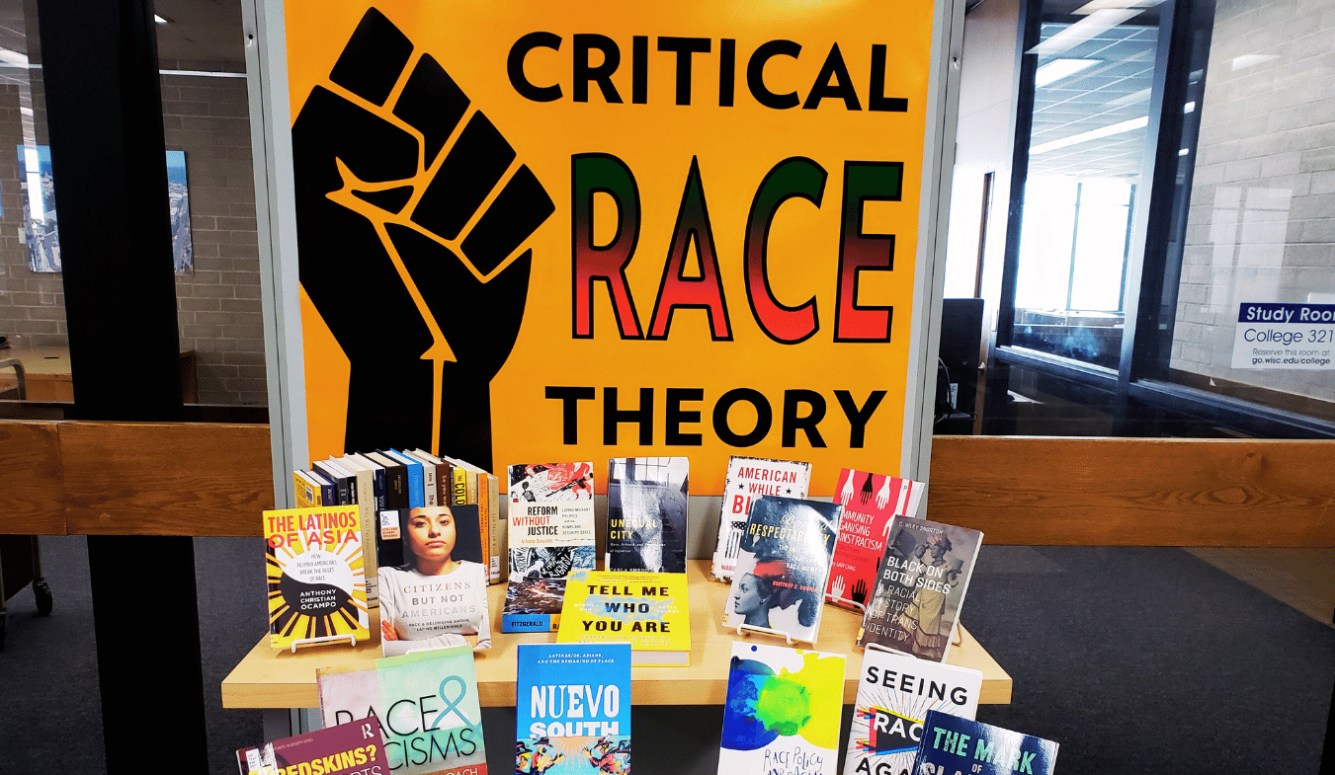

critical race theory

Demystifying Critical Race Theory

Activists on both sides have an incentive to keep Critical Race Theory undefined and ambiguous.

Editor’s Note: This piece was first published in Areo Magazine in April 2023.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) originated in higher education, but its political relevance has become more than academic, especially in the United States. Although CRT sprung from legal scholarship, proponents have pushed for its wholescale integration into education, medical training, psychology, and the social sciences as a whole.

CRT has also been the subject of intense political controversy. Many US states have introduced bills to restrict its teaching, sometimes on the grounds that it is not “factual and objective” or that it can “distort historical events.” As a result, both proponents and opponents have a vested interest in defining CRT in whatever way supports their agendas.

Indeed, several media outlets and organisations have published simplified explainers framing CRT either positively or negatively. These conflicting accounts make it hard to tell what critical race theory is—let alone formulate coherent opinions about CRT-related policy.

Definitions and Obfuscations

Even in the original academic literature, it is hard to find a consistent definition of critical race theory. Writing in 1995, Derrick Bell, one of CRT’s founding members, describes it as “a body of legal scholarship,” but CRT has clearly extended well beyond its legal origins since then and has been variously described by its practitioners as an “academic concept,” a “framework” both “theoretical” and “pragmatic,” “a pedagogical approach,” and a social “movement.”

Early critical race theorists were reluctant to pin the fledgling field down to a specific definition.

As Veronica Gentilli explains:

Critical race theorists seem grouped together not by virtue of their theoretical cohesiveness but rather because they are motivated by similar concerns and face similar … challenges. … The main question for critical race scholars is how to attack a legal system that disempowers people of color; their shared goal is one of political reform.

Thus, it should not be surprising that summaries and definitions of CRT have varied over the years. For example, theorists have compiled lists of critical race theory’s three tenets, four themes, five precepts, six unifying themes, seven tenets, eight themes and even specific principles customised for particular fields (e.g., social work). While there are certain common elements, there is often fierce disagreement as to how and when to apply them. Stephanie Phillips, who describes CRT as “nebulous,” recounts a debate over a list of tenets that were proposed at a critical race theory workshop:

Critical Race Theory:

1. holds that racism is endemic to, rather than a deviation from, American norms;

2. bears skepticism towards the dominant claims of meritocracy, neutrality, objectivity, and color-blindness;

3. challenges ahistoricism, and insists on a contextual and historical analysis of the law;

4. challenges the presumptive legitimacy of social institutions;

5. insists on recognition of both the experiential knowledge and critical consciousness of people of color in understanding law and society;

6. is interdisciplinary and eclectic (drawing upon, inter alia, liberalism, post-structuralism, feminism, Marxism, critical legal theory, post-modernism, and pragmatism), with the claim that the intersection of race and the law overruns disciplinary boundaries; and

7. works toward the liberation of people of color as it embraces the larger project of liberating all oppressed people.

According to Phillips, the discussion surrounding the first six points “went fairly smoothly,” but “all hell broke loose” regarding the final clause. There was a lengthy argument as to “whether gay men and lesbians are ‘oppressed people’ and if so, whether their liberation had anything to do with the fight against racial oppression.” The group ultimately resolved to include gay and lesbian rights as “an integral part of the antiracist struggle,” though only after eight years of heated argument.

To complicate matters further, activists on both sides have an incentive to keep critical race theory undefined and ambiguous. Proponents may redefine it as needed; critics may cite extreme claims as representative. Defenders can dismiss these same criticisms as unrelated to what CRT actually is and accuse such critics of fostering a moral panic. But for those interested in understanding CRT, the ambiguity and fluidity of these definitions can be frustrating.

A Lesson from Religion

Such definitional problems are by no means unique to critical race theory. Religious studies faces similar questions about which ideas, practices, people, and groups are considered representative of the field. As with CRT, we find debates over the definition and meaning of the word religion. Some definitions are so broad that they render the concept meaningless, while others are so specific that they exclude some important religions. As Martin Riesebrodt writes:

[T]he concept of religion is in crisis. Some people dilute it to the point of futility, considering barbecues with guitar music, soccer games, shopping in supermarkets, or art exhibitions to be religious phenomena. Everything becomes “somehow” or “implicitly” religious. Others criticize the concept of religion as an invention of Western modernity that should not be applied to premodern or non-Western societies. In their opinion, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism are Western inventions that cannot be termed religions without perpetuating colonialist thinking. When soccer games are seen as religious phenomena and the recitation of Buddhist sutras is not, something has obviously gone wrong.

Even when we focus on a specific religion—e.g., Judaism—we still have to make value judgments as to which beliefs and practices are authentic and legitimate. The parameters of what is and is not Jewish have been debated for centuries. One solution to this dilemma is to shift from a top-down perspective that begins with the discussion of theories to a bottom-up perspective that looks at beliefs and practices and generalises based on that data. We can see this approach in Shahab Ahmed’s treatment of Islam:

To my mind, when Muslims claim to be speaking and acting as Muslims, that is, to be speaking and acting in Islam we need … to take them at their word … My point is not that “whatever Muslims say or do is Islam,” but that we should treat whatever Muslims say or do as a potential … expression … of being Muslim/Islam—and … informed by the value of Islam/Islamic.

For Ahmed, an action is Islamic if the individual identifies as a Muslim and his or her actions are performed in the name of Islam.

I suggest adopting a similar bottom-up approach towards critical race theory. Rather than arguing about what CRT is and is not, we should look at the claims, arguments, and methods used by critical race theorists when they themselves claim to be doing critical race theory. We need to shift the discussion from CRT as a whole to individual claims made in its name. As with religion, I will leave it largely up to those in the CRT field to decide which claims are legitimately central to CRT.

Competing Paradigms

Let’s begin with a passage from Critical Race Theory: An Introduction by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, since Delgado is widely recognised as one of the founders of critical race theory. Delgado and Stefancic assert:

Unlike traditional civil rights, which embraces incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.

For Delgado and Stefancic, the premise of CRT is “that racism is ordinary, not aberrational—‘normal science,’ the usual way society does business, the common, everyday experience of most people of color in this country.” When Delgado and Stefancic refer to “normal science,” they are borrowing a term from Thomas Kuhn’s 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The term describes the dominant way of thinking on which all research is based and evaluated:

[“N]ormal science” means research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievements, achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice.

According to Kuhn, scientific discoveries are never made in isolation but depend on fundamental a priori assumptions that he calls paradigms. These include “standard examples of solved problems” that serve as templates for subsequent inquiry and the shared set of assumptions that enable a scientific community to reach “relative unanimity” as to which problems to solve and what constitutes an appropriate solution. These paradigms are determined and upheld by scientific communities themselves. Kuhn argues that scientific dissenters—like religious heretics—are frequently ostracised or excommunicated. According to Kuhn, intellectual knowledge is therefore the result of social factors as much as anything else and scientific knowledge is not produced by individuals, but communities. Members of the intellectual establishment have a personal vested interest in perpetuating these paradigms and resisting anything that challenges them.

Although Kuhn himself expresses frustration with the ways in which his theory has been applied to areas outside history of science, many have argued that all areas of human knowledge have their “normal science” of the status quo. As legal theorist Charles Lawrence puts it,

The dominant legal discourse is premised upon the claim to knowledge of objective truths and the existence of neutral principles. We must free ourselves from the mystification produced by this ideology. We must learn to trust our own senses, feelings, and experiences … even (or especially) in the face of dominant accounts of social reality that claim universality.

CRT practitioners tend to be sceptical of claims that there is such a thing as objective truth, believing instead, as Delgado and Stefancic explain, that “truth is socially constructed” and contingent on “the mindset, status, and experience of the knower.” This is also true of historical truth—and this creates a need for a “revisionist history” that “re-examines America’s historical record, replacing comforting majoritarian interpretations of events with ones that square more accurately with minorities’ experiences.” This idea that truth is socially constructed is also central to CRT’s approach to law and justice, influencing “the idea that not every legal case has one correct outcome. Instead, one can decide most cases either way, by emphasizing one line of authority over another, or interpreting one fact differently from the way one’s adversary does.”

When confronted with the argument that storytelling is not an authentic source of true knowledge, Delgado counters that the dominant majoritarian narratives are themselves the results of “self-serving” storytelling disguised as truth:

Majoritarian tools of analysis, themselves only stories, inevitably will pronounce outsider versions lacking in typicality, rigor, generalizability, and truth. The purpose of many outsider narratives is to put our very ordering principles, including these, in question. Empowered groups long ago inscribed their favorite narratives—ones that reflected their sense of the way things ought to be—into myth and culture. Now they profess to consult that culture, meekly and humbly, in search of standards for judging challenges to that culture. Neat. But circular.

This notion of different truths for different cultures is reminiscent of Kuhn’s idea of competing paradigms that are so incommensurable that it is as if their respective proponents “practice their trades in different worlds.” But according to Kuhn, the strength of a paradigm lies in its ability to solve problems. Its proponents must “have faith that the new paradigm will succeed with many large problems that confront it, knowing that the older paradigm has failed.” So, does CRT manage to solve the problems it identifies?

Grappling with the Concept of Merit

One such problem is the concept of merit. According to Delgado, merit masquerades as an objective criterion, while actually reflecting only the subjective perspectives of those making the evaluations. As CRT scholars note, because the people in power are typically white, standards of merit “in fact serve the interests of the white majority.” In response to these claims, Daniel Farber and Suzanna Shery point to the successes of Jewish and East Asian scholars, who are disproportionately represented in academia. They argue that if merit is merely an illusion designed to reinforce white supremacy, the implications for Jews and Asians are not only troubling but, in the case of Jews, also echo antisemitic conspiracy theories. Tomiwa Owolade has also discussed these disturbing implications of anti-racist logic. If favouritism and prejudice explain the dearth of some minorities in academia, they should also explain the overrepresentation of other minorities.

Instead of addressing this argument, Delgado evades the issue entirely, “To require that Latinos and blacks have at the ready a complete explanation for the wholly commendable success some Jews have enjoyed in education and the professions, as a price for coalition, seems odd.” But the appeal to race is completely inappropriate here. Farber and Sherry make no such demands of “Latinos and blacks”: they are questioning a narrative about merit. Many of the scholars who promote that narrative are white (and many non-white scholars disagree with it).

Justice and its Discontents

Delgado relies on Kuhn’s idea of competing paradigms to challenge majoritarian presumptions of truth and authority. However, the same Kuhnian arguments can easily be used to subvert the critical race theory project. According to Kuhn, all paradigms, including upstart ones, preach to the converted, using circular arguments that are unconvincing to outsiders:

Each group uses its own paradigms to argue in that paradigm’s defense … the circular argument … cannot be made logically or even probabilistically compelling for those who refuse to step into the circle.

Furthermore, Kuhn questions truth claims in general. According to Kuhn, the utility of a scientific paradigm depends on the problems it solves, but “you cannot describe the other science as false.” This contrasts with Delgado’s claim that society’s “normal science” is racism and that CRT provides a corrective. This is a moral evaluation, and it implies that the prevailing paradigm is false and critical race theory is true. But if all knowledge and truth “is socially constructed,” as Delgado and Stefancic argue, then CRT cannot claim to be a superior alternative to the conventional account of things because there is no universal objective standard by which to judge—all truth claims are merely subjective, and all morality is relative.

This contradiction is evident in the following remarks by CRT defenders Gilah Kletenik and Rafael Neiss:

Decolonizing is a matter of justice. It starts with correcting the historic marginalization of researchers and subjects that are not cisheteromale, able-bodied, and white. It must also dispense with fictions of “neutrality” or the “marketplace of ideas,” while unmasking allegiance to “standards,” “merit,” and “rigor” as ideology disguised as impartial metrics.

The authors reject “standards” such as “merit” and “rigor,” which they see as purely ideological, but they do so in the name of “justice”—which they present as an objective universal standard. However, as Ronald Dworkin has pointed out, justice is “the most distinctly political of the moral ideals” and definitely more subjective and ideological than something like a SAT score.

Some CRT scholars themselves have noted this incongruity. Veronica Gentilli writes,

Critical Race scholars have a double challenge: On the one hand, they must dispel the myth of objectivity that underlies our current understanding of the law and its moral foundation, while on the other, they must prove that it is possible to obtain a true and objective conception of justice.

For Angela Harris, this is because CRT is caught between modernist and postmodernist narratives, which are “at war with one another … in the way they see the world”:

Sometimes CRT seems to be asking the reader to accept outsider stories as ‘true’ in a conventional sense; other times, CRT seems to call ‘truth’ itself into question.

However, Harris finds this seeming contradiction a “source of strength” and argues that it “inspires a jurisprudence of reconstruction—the attempt to reconstruct political modernism in light of the difference ‘race’ makes.” This is incoherent, perhaps even deliberately so.

The Appeal to Rights

Some argue that CRT does not require ideological or methodological consistency, as it is focused on the effects of political policies. In the words of Mari Matsuda, “The prescriptive message of outsider jurisprudence offers signposts to guide our way there: the focus on effects.” Depending on the situation, either a modernist or postmodernist approach could result in an advantage over the white majority establishment. Thus, certain CRT claims can be seen as post-hoc rationalisations, designed to achieve specific ends. As Richard Primus explains,

It is not yet clear how, if at all, a legal theory can coherently merge the deconstructive posture of critical legal studies with the celebration of traditionally conceived notions of rights. My own suspicion is that it cannot be done, at least not from a purely philosophical perspective which judges theories by their intellectual consistency. Critical race theory, however, is avowedly political, measuring its success not just by those abstract philosophical standards but also by the concrete results it can achieve for its vision of society.

This explanation suggests that critical race theory doesn’t even aspire to intellectual coherence, but just uses whatever rhetoric the situation demands—which sometimes includes an appeal to universal human rights. However, such an appeal can undercut the goals of critical race theory. If rights are universal, they protect everyone, even members of the white majority. As Mark Tushnett complains, “the rhetoric of rights is available to anti-progressives.” In such cases, critical race theorists may treat the very concept of rights with suspicion. In other words, for certain critical race theorists, rights have no intrinsic meaning or value, but are merely tools used to achieve desired ends.

Colourblindness, Racism, and Power Dynamics

There are similar contradictions inherent in critical race theory’s critique of colourblind policies, i.e., policies that avoid taking race into account, on the presumption that unequal treatment based on race is morally wrong. But if we don’t think it’s wrong to treat people of different races differently, how can we object to the racist policies of the past? As Chief Justice John Roberts puts it, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Many critical race theorists disagree. As Delgado and Stefancic explain:

Critical race theorists … hold that color blindness will allow us to redress only extremely egregious racial harms, ones that everyone would notice and condemn. But if racism is embedded in our thought processes and social structures … then the “ordinary business” of society—the routines, practices, and institutions that we rely on to effect the world’s work—will keep minorities in subordinate positions. Only aggressive, colour-conscious efforts to change the way things are will do much to ameliorate misery. As an example of one such strategy, one critical race scholar proposed that society “look to the bottom” in judging new laws. If they would not relieve the distress of the poorest group—or, worse, if they compound it—we should reject them.

In this view, while colourblind policies may be well intentioned, in effect they ossify systemic racism, since the racism embedded in society cannot be undone by returning to a neutral state of affairs, but only by actively redressing the balance by discriminating in favour of racial minorities. But if racial discrimination is fundamentally unjust, we are simply perpetuating that injustice if we continue to discriminate on the basis of race. One approach to this problem distinguishes between “individual justice” and “group justice.” According to this view, discriminating against certain groups may be justified for “the common good,” even if the individual members of those groups were “not personally responsible for society’s transgressions.”

Challenging the Presumption of Innocence

Some critical race theorists view the presumption of innocence as misguided, as it impedes the victims of racial discrimination from obtaining justice from the predominantly white establishment. Alan David Freeman, for example, argues:

The fault concept gives rise to a complacency about one’s own moral status; it creates a class of “innocents,” who need not feel any personal responsibility for the conditions associated with discrimination, and who therefore feel great resentment when called upon to bear any burdens in connection with remedying violations. This resentment accounts for much of the ferocity surrounding the debate about so-called “reverse” discrimination.

Delgado and Stefancic are more explicit:

A much more subtle and complex version of white privilege sometimes appears in discussions of the fairness of affirmative action programs. Many whites feel that these programs victimize them, that more qualified white candidates will be required to sacrifice their positions to less qualified minorities. So, is affirmative action a case of “reverse discrimination” against whites? Part of the argument for it rests on an implicit assumption of innocence on the part of the white displaced by affirmative action. The narrative behind this assumption characterizes whites as innocent, a powerful metaphor, and blacks as—what? Presumably, the opposite of innocent. Many critical race theorists and social scientists alike hold that racism is pervasive, systemic, and deeply ingrained. If we take this perspective, then no white member of society seems quite so innocent.

For Delgado and Stefancic, any white member of a systemically racist society bears some responsibility for society’s racism. They are automatically guilty simply because they are part of that collective.

Another way of justifying race-conscious policies is to define racism as contingent on power dynamics. Mari Matsuda, for example, advocates “legal sanctions for racist speech” because of the effects such speech has on its victims:

Victims of vicious hate propaganda have experienced physiological symptoms and emotional distress ranging from fear in the gut, rapid pulse rate and difficulty in breathing, nightmares, post-traumatic stress disorder, hypertension, psychosis, and suicide.

Such protections should, however, not extend to “expressions of hatred, revulsion, and anger directed against historically dominant-group members by subordinated-group members” because “Racism … comprises the ideology of racial supremacy and the mechanisms for keeping selected victim groups in subordinated positions.” Even though, elsewhere in the piece, she defines racism as “disparate treatment” for people of different races, Matsuda argues that it is not racist to prosecute white people for hate speech, but not non-white people, because of society’s racial power dynamics. She sees this as analogous to the way in which defamation laws differentiate between public and private figures. It is more difficult to sue someone for defamation of a public figure and that is because, she argues, public figures have access to a “safe harbor” that they can retreat to, which mitigates the effects of harmful speech against them. And so, she suggests, do white people. They should be treated differently because hate speech won’t have as big an impact on them.

Matsuda’s larger argument, however, is about the importance of “considering the victim’s story” when framing laws. It is essentially, then, a plea for empathy. However, everyone feels emotions. Shouldn’t we also empathise with the accused, since some accusations are false? Policy based on empathy is necessarily selective because it must respond to the feelings of some people, while disregarding the feelings of others. As Toni Massaro explains:

Professor Matsuda asks that we give greater value to the victim’s story than to that of the first amendment absolutist, or to that of the promoter of racial hatred. [But] The significant … questions … are not whether judges and law should “empathize” … but with whom we should empathize? Which stories should law privilege?

Matsuda acknowledges that “the selective consideration of one victim’s story and not another’s results in unequal application of the law,” yet she is not only unbothered by that but seems surprised to have encountered “incredulity, scepticism, and even hostility” to her ideas from those whose rights she would like to curtail. Again, this is muddled thinking and leads to incoherent conclusions.

CRT’s Wider Influence

Many approaches that do not evoke CRT by name seem to have influenced by CRT or share similar ideas. For example, in 2020, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture posted an infographic on its website entitled, “Aspects & Assumptions of Whiteness & White Culture in the United States.” Based on the work of Judith Katz, the infographic described “Objective, rational, linear thinking,” “Delayed gratification” and “Be polite” as traits associated with “whiteness” on the grounds that, since whites represent the “dominant culture” and “hold most of the institutional power,” these qualities merely reflect the preferences of the white establishment. (The museum ultimately apologised and removed the infographic after receiving pushback, but similar ideas are still common in corporate training materials). When the Smithsonian tweeted that they had removed the chart, political commentator Ben Shapiro responded, “The problem ain’t the chart. The problem is the entire propagandistic critical race theory effort.”

Most of the public debates about CRT that involve examples like this one do not mention CRT by name, but seem influenced by similar thinking. It seems reasonable to include them in this discussion—especially given that, according to critical race theorists themselves, CRT represents a “framework” or “paradigm” for viewing society and is constantly evolving and being deliberately adapted to different applications. However, not all such arguments are made in good faith. CRT is often evoked as an all-purpose bugbear by people who simply want to attack a variety of things that they dislike. We must always demand reasonable evidence of a connection with CRT-influenced ideas, on a case-by-case basis.

Is Critical Race Theory a Religion?

Many critics derisively refer to CRT as a religion, dogma, or cult because it has certain characteristics in common with many religions. But these characteristics are not unique to religion, but are typical of many different ideologies, including secular ones.

So, CRT is not necessarily a religion—even though some critical race theorists employ religious language themselves—for example, describing themselves as “converted to a new understanding” or embarking on “a next generation project of human liberation”—or even openly describe CRT as a spiritual practice or explicitly reference religious texts. For example, Gloria Ladson-Billings writes:

I would point us toward Pauline pronouncements that suggest “we have this treasure in earthen vessels” (2 Cor. 4:7), that is, CRT is a theoretical treasure—a new scholarly covenant, if you will, that we as scholars are still parsing and moving toward new exegesis. And about that, somebody ought to say ‘Amen.’

But there will always be people who draw on religious language to express strong moral convictions. And the debates about critical race theory provoke strong emotional reactions precisely because the theory addresses fundamental moral concepts and ultimately appeals to people’s internal convictions and beliefs (especially to their beliefs about fairness)—though not usually to their belief in the supernatural. In a sense, CRT practitioners and their critics are like two groups with competing interpretations of a religious text. Each side judges its arguments superior and applies its own standards. As we have seen, the tools forged to destroy the master’s house can easily be used to dismantle any replacement edifice. Ultimately, despite—or perhaps because of—the many disagreements between scholars and the many sceptics and non-believers, religious studies continues to thrive as an academic field. As with CRT, religious ideas and values also permeate civil society and political discourse. Many religious adherents have learned to accept and live with those with whom they disagree vehemently. Whether critical race theorists are open to compromise of this kind remains to be seen.