A full audio version of this article can be found below the paywall.

In his masterpiece Al-Muqaddima, the 14th-century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun observed that, in a landscape of contending tribes, history is shaped by the use of force more than any other factor. Today, the Arabic-speaking Middle East is not a throng of some 300-million people united by a common ideology and shared interests; it is a diverse and dynamic region, seventy percent of which is Sunni Muslim with the remainder populated by dozens of minorities. Syria, with its own Sunni-Arab majority of seventy percent, may be representative of the region demographically, but it is distinguished by the rule of a minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shia Islam.

In recent days, a surprise rebel offensive has managed to capture Aleppo, Syria’s second-largest city, and now threatens to seize more territory. This swift Turkish-backed blitzkrieg has exposed the Ba’athist regime of Bashar al-Assad to its most serious challenge since the outbreak of the Syrian revolt more than a decade ago. The Assad family temporarily absconded to Moscow until the immediate danger of Damascus being sacked had passed. Syrian government warplanes have since responded by pounding Aleppo for the first time since 2016, and Russian military assets have been engaged in an effort to check the rebels’ advance.

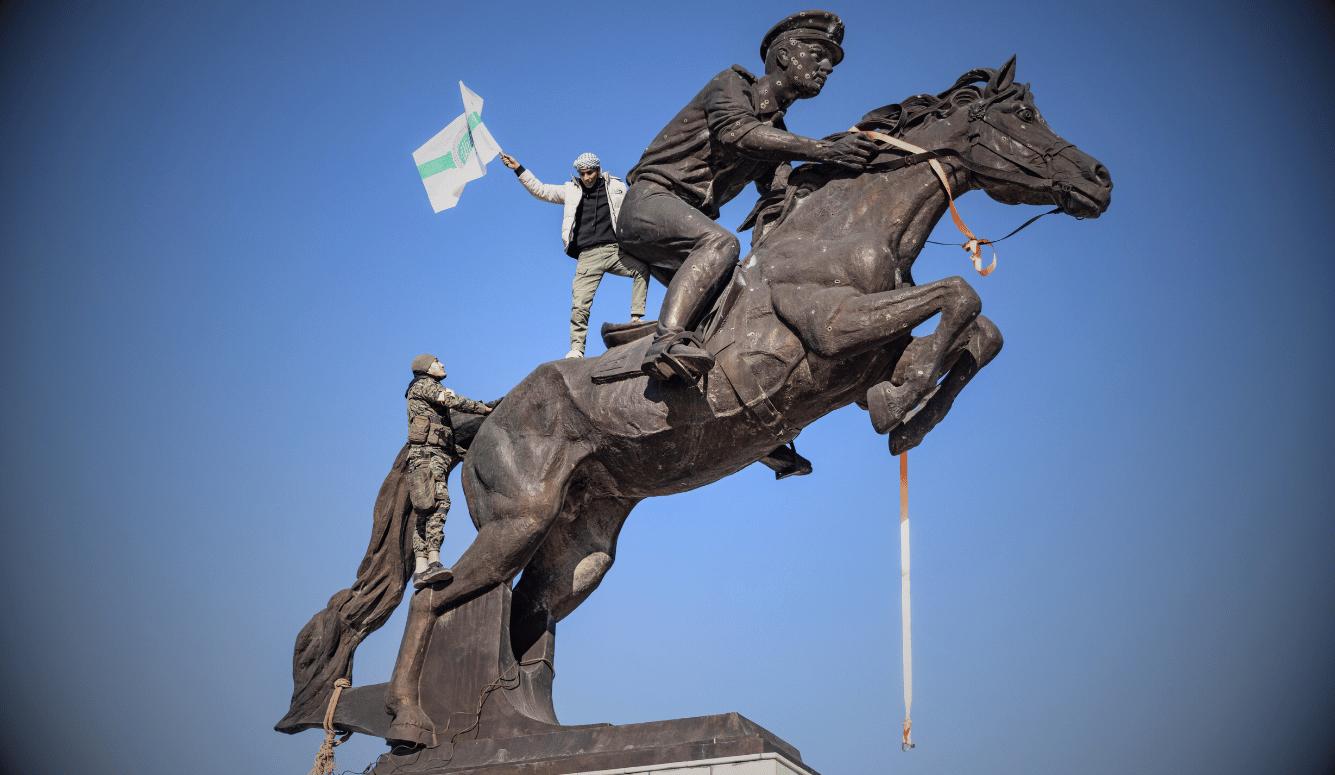

The rapid rebel offensive represents the intense escalation of a civil war that had been mostly dormant for years, and it has resurfaced the country’s enormous ethnic and religious complexity and contending geopolitical interests. Loose talk of “liberated” cities is certainly premature given the Islamist cast of the militant groups responsible for the retreat of government forces. The rebel alliance that has taken Aleppo is led by HTS—Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (“Organisation for the Liberation of the Levant”)—with some 30,000 fighters. HTS was formerly affiliated with al Qaeda but has since renounced global jihad in favour of toppling Assad and resisting Iranian imperialism, but it remains a designated foreign terrorist group by the US State Department.