Art and Culture

‘Bright Lights, Big City’ at Forty

Jay McInerney’s debut novel was the first work of fiction to explore yuppie culture, and its success changed American publishing.

Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney’s debut novel, was published in 1984 and thus celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year. If you are under sixty years of age, this probably doesn’t mean much to you, but by the time McInerney’s book arrived, literary fiction had been in the doldrums for most of the late 1970s and early 1980s. That period is fascinatingly documented in Dan Sinykin’s recent book, Big Fiction. Sinykin quotes Gary Fisketjon, a legendary Random House editor, who told an interviewer, “When I came into the business in the late 70s, [literary writers] couldn’t even get published because they sold so poorly in hardcover and they never went into paperback. There was a backlog of very good writers who were wildly under-published for a period of years. It was a good time for a kid to come into it because you had a lot accomplished writers to choose from.”

In this vacuum stepped McInerney, the first breakout star of his literary generation and one of the most prominent members of the so-called “literary Brat Pack,” which included writers like Bret Easton Ellis, Tama Janowitz, Susan Minot, Donna Tartt, and a handful of others. They took their collective name from a group of young actors—Emilio Estevez, Andrew McCarthy, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy etc—who were becoming Hollywood stars around the same time that McInerney and his cohort were becoming publishing sensations. The “Brat Pack” name was itself a playful reference to the “Rat Pack,” a gang of Hollywood celebrities in the 1950s—Frank Sinatra, Joey Bishop, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, and a handful of others—who liked to hang out, drink, chase women, and generally be seen together at various glamorous venues in New York, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles.

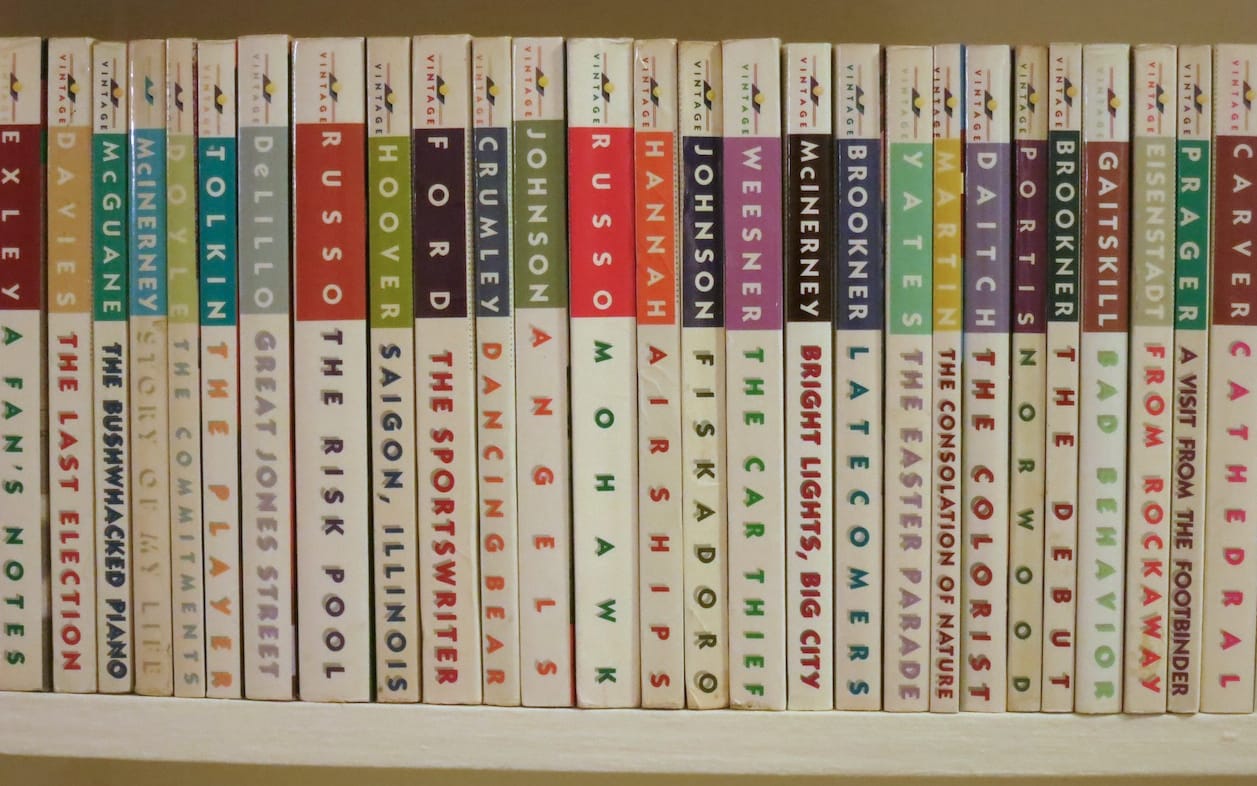

Before he went to work at Random House, Fisketjon was Jay McInerney’s college classmate at Williams. In the early 1980s, when McInerney was earning an advanced degree at Syracuse, he would spend his summer breaks at Fisketjon’s loft apartment in the East Village, which was where he began writing BLBC. After joining Random House, Fisketjon made his name by creating the Vintage Contemporaries series of trade paperback books. Trade paperbacks are larger and more costly than mass-market (or pocket) paperbacks, but they are less expensive than hardback books. Vintage Contemporaries had a very distinctive cover layout that made them attractive to the kinds of people who like to collect book series.

Fisketjon originally planned to republish the best works of established but under-appreciated literary authors in his Vintage Contemporaries series, along with a select handful of original novels by newer writers. He hoped that the latter’s association with the former would help those new young writers find an audience. The first four books in the VC series were Bright Lights, Big City, written by McInerney, and three older titles—one each from Raymond Carver, Thomas McGuane, and Peter Matthiessen—brought back into print after they underperformed in hardback. McInerney was initially resistant to the idea of publishing BLBC as a paperback original, a format generally synonymous with “commercial hack work” back then. But Fisketjon convinced him that appearing in the same striking series of trade paperbacks as Carver and company would allow him to ride the coattails of their reputations.

As it turned out, it was McInerney who had the long coattails. The media became fascinated by the notion of a new generation of young writers breaking into print not, as Hemingway and Fitzgerald had, with stately hardback books published the old-fashioned way, but in low-cost trade paperbacks with hip and edgy artwork. “Bright Lights, Big City was a smash,” Sinykin marvels. “In a reversal, it was McInerney who gave Carver, McGuane and Matthiessen a boost. The debut went through fourteen printings and sold more than two hundred thousand copies in the first eighteen months. Now everyone wanted a trade paperback series.” It was McInerney who helped pave the way for all the Brat Packers who would ride the paperback-original gravy train to commercial success.

But that was a long time ago. The intervening forty years haven’t been especially kind to either McInerney or Bright Lights, Big City. By now, the conventional wisdom surrounding McInerney’s career has hardened into a truism. Most people in the literary world familiar with his work will tell you that, after a very promising debut novel, McInerney allowed himself to get caught up in the worlds of celebrity and high society that he mocked in his work. As a result, after Bright Lights, Big City, his literary career became a classic case of diminishing returns. His debut novel drew comparisons to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and many people were expecting that McInerney would go on to do for the Reagan era what Fitzgerald had done for the Jazz Age—immortalise some of the New Yorkers who embodied its restless, materialistic essence. Instead, a number of older critics felt it necessary to put McInerney in his place by essentially proclaiming, “You, sir, are no F. Scott Fitzgerald!”

In May 1992, Adam Begley published a snotty profile of McInerney in the Los Angeles Times headlined, “Little Jay: Happy at Last: The Rake of Lower Manhattan Has a New Wife (No. 3), a New Book (No. 4) and a New Home (Very Far South of SoHo).” Here’s the money quote:

Last year, in the New York Review of Books (home to many a stalwart culture guardian), he published a substantial, keenly observed essay on the short stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. McInerney likes to encourage comparisons between his career and Fitzgerald’s. It’s a bad idea, mainly because Fitzgerald’s best writing is clearly great writing—not a distinction one could claim for the author of “Bright Lights,” no matter how many copies the book sells. McInerney knows that he hasn’t written anything on a par with “Gatsby,” yet he can’t help identifying with this early exemplar of the author as celebrity.

Begley is a conventionally minded journalist with an elite background (Harvard, Stanford, son of a Harvard-educated lawyer/novelist), so you can’t expect him to question the greatness of any book listed in Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon. I’m not as impressed by pedigree as Begley is, so I’m happy to play the unlettered buffoon and declare that I much prefer Bright Lights, Big City to The Great Gatsby (or The Catcher in the Rye, or As I Lay Dying, or many other classic American novels). Earlier this year, the editors of the Washington Post’s Book Club asked their readers, “Which classic novels are overrated?” The Catcher in the Rye was the overwhelming choice of the Post’s readers, but Gatsby was a solid runner-up. Here’s what WaPo Book Club member Daniel McMahon had to say about Fitzgerald’s “masterpiece”:

Humorless, joyless, and intellectually pedestrian, this novel is not just overrated—it’s not good. It is the Emperor’s New Clothes of novels that “beats on” because it is so endlessly assigned and students are told it is a classic. I suppose if one has read only 10 novels in one’s life (or high school career) that it might seem to be the best of those.

For me, the dumbest thing about Fitzgerald’s book is its portrait of working-class America as a blighted ash heap overseen by the empty spectacles of a god in ruin. Clearly, Fitzgerald never spent much time with Middle Americans, who are generally much more fun to hang around with than the Ivy Leaguers. Fitzgerald wrote some excellent short stories (mostly set in Europe or Hollywood or New York City), but he wasn’t much of a novelist. Gatsby appeals to teachers of American literature because it is short and full of heavy-handed symbolism.

I am sympathetic to the plight of America’s high-school teachers. I don’t blame them for assigning relatively short and easy-to-read books like Catcher and Gatsby to their students, many of whom are unlikely to make it through anything longer or more difficult. But just because those books remain on many high-school reading lists, it does not make them great books. It makes them books that are easy to teach. I wouldn’t call BLBC an all-time masterpiece of world literature, but it seems to capture the denizens of its rarified milieu (young, upwardly mobile, elite-educated New York professionals) with humour and sympathy and a lack of sentimentality. I say “seems to capture” because I have never actually visited that milieu, so I don’t really know how its denizens behave. But BLBC certainly felt authentic when I read it in the mid 1980s. And when I re-read it recently, it felt positively prophetic.

The term “yuppie” (slang for young, upwardly mobile, urban professional) first appeared in print in 1980, and was frequently employed by journalists in the years that followed. But McInerney seems to have been the first novelist to have actually succeeded in capturing what a yuppie was. His unnamed second-person narrator (he refers to himself as “you” rather than “I” throughout the book) is a graduate of an elite college, works as a fact-checker at the New Yorker (although the magazine is never named), and aspires to be a fiction writer (although, by the end of the novel, it seems more likely that he’ll end up going back to college for a law degree or taking a job on Wall Street). His leading characteristic is that he has had a world of privilege laid at his feet but spends much of his time pissing it all away on cocaine, alcohol, and impersonal sex.

For most Americans, having thrown away an opportunity like this, they would never get a chance to win it back. But BLBC makes it pretty clear that, if you go to the right schools and make the right social connections, you pretty much can’t fail. McInerney’s narrator does almost nothing but fuck up throughout the novel, and yet, by the end, we’re left with the impression that he will eventually get his act together and become a wealthy professional, marry another highly educated professional, and live in some high-end Connecticut suburb of New York City. Even his boss at the New Yorker, where he becomes only the second person ever to be fired, promises to write him a glowing letter of recommendation. Had McInerney’s narrator been a young community-college grad from an impoverished family, his voracious appetite for cocaine would probably have landed him in jail for what remained of his youth. And by the time he was done paying for that mistake, it would likely be too late for him to attain even a decent middle-class life, much less a wealthy Connecticut one.

To some extent, we have always lived in that world, a world in which the rich and well-bred are often afforded an eighth, ninth, or even a tenth “second” chance. But in previous generations, this was more or less a matter of being born into it. What McInerney understood, and what he illustrated in BLBC, was that the new meritocracy wasn’t likely to be any better than the old aristocracy it was replacing. McInerney’s narrator doesn’t come from a rich or noteworthy family—his parents have just enough privilege to afford an elite education for their offspring. But, in Reagan’s America, an elite education, and the connections that came with it, proved to be a new kind of safety net—the kind that allowed the privileged to screw around and fail over and over again and still not go completely bust.

The past four decades have brought us a number of examples of the type of elite idiots that McInerney describes in his book—screw-ups who fail relentlessly upwards. Re-reading the novel recently, I realised that McInerney was describing the world that would soon give us the likes of Hunter Biden, Jared Kushner, Donald Trump Jr., Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Paris Hilton, William Kennedy Smith, and countless others who have contributed almost nothing good to society but have nonetheless never been in any danger of winding up penniless and ashamed. These people would have been remittance men (or women) in a previous era. Nowadays, they are impossible to get rid of.

To an old man like me (born three years after McInerney), BLBC still seems like a relatively recent book. But, as I re-read it, I realised that the America described in its pages is much closer in spirit to the America of the 1950s than to the America of the smartphone era. When the narrator’s fashion-model wife runs away to Paris, he tells us, in his second-person narrative voice, “After three days of transatlantic telexes and calls you located her in a hotel on the left bank.” Later, the narrator finds a note from his friend Tad slipped under his apartment door. It begins, “Having this messengered to your digs after numerous calls to reputed place of employ.” Nowadays, most of us can communicate instantly, at any time, with the people who are closest to us. We don’t have to send telexes or have handwritten letters carried to an apartment by a bicycle messenger. Even if my wife were in Zaire, I could communicate with her instantly from my home in Sacramento. In this respect, BLBC now seems rather quaint.

There are also lines in Bright Lights, Big City that would make no sense to most Americans too young to remember, say, cigarette advertisements. At one point, the narrator says of his co-workers, “They are not convinced that you’d rather switch than fight.” Unless you are familiar with the old Tareyton Cigarette slogan, “Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!” McInerney’s line makes little sense. But it often seems as if McInerney was able to see into the future as he was writing BLBC. Unsurprisingly for a novel set in New York City, there are several references to the twin towers of the World Trade Center, but the final three-page section of the novel begins with these words that read eerily like an elegy: “The first light of the morning outlines the towers of the World Trade Center at the tip of the island.” Elsewhere in the novel, at a dance club, McInerney’s narrator notes that, “Elaine moves with an angular syncopation that puts you in mind of the figures on Egyptian tombs. It may be a major new dance step.” Two years after the book was published, the Bangles would top the American charts with “Walk like an Egyptian,” a hit that kicked off a craze for dancing in a manner that mimicked the figures on Egyptian tombs.

The Bangles 🎩🪄 Walk Like An Egyptian "1986" #IWantMy80s #TheBangles pic.twitter.com/mtKRqepV2q

— Music Jim 🎃👻🎃🎩🪄 (@MusicJim2) October 3, 2024

At the New Yorker, the narrator works in the Department of Factual Verification, which allows McInerney to occasionally muse on the difference between facts and truths. When his boss tells him fact-checking is important because, “Our readers depend on us for the truth,” the narrator writes, “You would like to say, ‘Whoa! Block that jump from facts to truth,’ but she is off and running.” Twice he quotes the Talking Heads song “Crosseyed and Painless”: “Facts all come with points of view/Facts won’t do what I want them to.” Nowadays, many media figures seem more obsessed with facts than they are with truth. In the early days of the pandemic, when there were only enough face masks available for medical professionals, we were told that face masks were not necessary for the general public. That “fact” was subsequently revised, and it is now difficult to remember what the truth was.

McInerney seemed to foresee that the media would write him off as a one-book wonder. Early in the novel, the narrator says to himself, “You could start your own group—the Brotherhood of Unfulfilled Early Promise.” Later, he writes, “But what you are left with is a premonition of the way your life will fade behind you, like a book you have read too quickly, leaving a dwindling trail of images and emotions, until all you can remember is a name.” It’s as if he was trying to preempt his critics by declaring himself a cautionary tale about the wages of early promise. Certainly, none of his later books would attain anything like the kind of cultural prominence of Bright Lights, Big City, but that was mostly just because the media had moved on to other literary wunderkinds.

When Nathan Englander published his story collection For the Relief of Unbearable Urges in 1999, the media proclaimed him the second coming of Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bernard Malamud, and Philip Roth all rolled into one. But his post-wunderkind career has been far less impressive than McInerney’s. Now he’s a middle-aged, mid-list writer, and academic. To one extent or another, the same fate befell most of McInerney’s fellow Brat Packers. Tama Janowitz never caught fire. David Leavitt and Ethan Canin have had fairly unspectacular careers. Ditto Susan Minot and Mona Simpson and any number of other writers who came out of elite writing programs in the 1980s. In the 32 years since the publication of her debut novel The Secret History, Donna Tartt has managed to produce just two more books. One of those won a Pulitzer, but I’m damned if I can tell you why. Only Lorrie Moore (born on McInerney’s second birthday) seems to have carved out a reputation as a Serious American Literary Author. Of all the Brat Packers, she is the one most likely to end up enshrined in the Library of America.

I continued reading McInerney’s work well into the 1990s. I thought 1988’s Story of My Life was nearly as good as BLBC. I went into Brightness Falls with a chip on my shoulder because, prior to reading that novel, I read an interview with McInerney in which he said he was inspired to write the book after asking himself, “What would Bonfire of the Vanities have been like if it were populated with real people rather than caricatures?” (or words to that effect). This kind of idle sideswipe is never a good look for a writer. In 2014, Isabel Allende appeared on NPR to promote her crime novel Ripper, and told her interviewer, “I’m not a fan of mysteries, so to prepare for this experience of writing a mystery I started reading the most successful ones in the market in 2012. ... And I realized I cannot write that kind of book. It’s too gruesome, too violent, too dark; there’s no redemption there. And the characters are just awful. Bad people.” Mystery fans responded negatively and her book sold poorly. I am a huge fan of Bonfire of the Vanities and I found the characters in that novel at least as convincing as McInerney’s. Nonetheless, I found that I enjoyed Brightness Falls in spite of my gripes with its author.

I also enjoyed McInerney’s 1997 novel The Last of the Savages. I almost didn’t read it after a review in the Atlantic practically accused McInerney of plagiarising Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. The review was titled “Robert Penn McInerney.” McInerney wrote a wounded response to the magazine, claiming he’d never even read All the King’s Men. The review was so inflammatory that the editor of the Atlantic took the unusual step of hiring another writer (I seem to recall it was Charles d’Ambrosio, but I can’t find it online) to read The Last of the Savages and All the King’s Men to see if the charge of near-plagiarism was warranted. D’Ambrosio (or whoever it was) sided with McInerney. Alas, after the Last of the Savages, I didn’t read any more of his novels, although I did read his story collection, How It Ended, and enjoyed it.

McInerney’s hostility towards Bonfire of the Vanities was understandable in a way. McInerney had pretty much invented the yuppie novel, and then Tom Wolfe came along and perfected it. Published in October 1987, Bonfire became the twelfth bestselling novel of 1987 and the eleventh bestselling novel of 1988. The massive (690-page) hardback sold roughly 725,000 copies in the US, and the paperback sold millions more. Neither book has been embraced by the literary establishment as a bona fide American classic, but that snub has been less harmful to Bonfire’s reputation than it has to that of BLBC. Wolfe was a conservative outsider to America’s liberal publishing establishment. Though enormously popular with readers, he was never fully embraced by the New York literary set—something he prided himself on. McInerney had a more conventional literary and academic background, courted the New York in-crowd, and mentored under a man, Raymond Carver, who was all the rage back in the 1980s. The fact that BLBC never got the imprimatur of the east coast literary elite probably hurt McInerney in a way that such a rejection could never have hurt Wolfe.

As it happens, both BLBC and Bonfire were adapted by Hollywood into films that became expensive flops. James Bridges’s 1988 adaptation of BLBC starred Michael J. Fox and Kiefer Sutherland, but it only earned $16 million on a budget of $25 million. Brian DePalma’s 1990 adaptation of Bonfire starred Bruce Willis and Tom Hanks, and only earned $15.6 million on a budget of $47 million. DePalma’s film was such a disaster that it inspired one of the best nonfiction works ever written about the film business, Julie Salamon’s The Devil’s Candy: The Anatomy of a Hollywood Fiasco, published in 1991. Both films have since been largely—and justifiably—forgotten.

The last great novel of the yuppie era was probably Tom Robbins’s 1994 book Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas (not to be mistaken for Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?, a novel by semi-Brat Packer Lorrie Moore). BLBC charted the rise of American yuppie culture. Bonfire of the Vanities charted its decadence. And Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas charted what Robbins seemed to believe would be its collapse. Robbins’s novel spans five days in April 1990, during which the New York Stock Exchange experienced one of its worst crashes. The protagonist is Gwendolyn Mati, a Filipina-American stockbroker in Seattle. Unlike the unnamed protagonist of BLBC, Gwen has embraced the yuppie ethos of endless economic growth showering massive rewards upon the educated classes who have learned how to financialise everything in American life. So, when the market crashes, she sees not just her portfolio but her entire worldview cratering.

Robbins chose to write his novel in second person, present tense, which suggests that he intended his book to be in conversation with BLBC—the alpha and omega of yuppie fiction. Alas, Robbins was wrong. The 1990 crash was just a bump in the road for America’s monied elite, and today, the yuppie ethos remains alive and well in America. His novel ends on 9 April 1990. To give you an idea of how long ago that was, it was the same day that 34-year-old actress Kristen Stewart was born, and she has now been a film star for two decades. If anything, the America that Stewart’s generation grew up in was even more of a financialised, winner-take-all society than the one that existed in 1984 when BLBC was published.

Gary Fisketjon’s embrace of the paperback-original aesthetic back in the 1980s gave much Brat Pack fiction a cool and edgy vibe that may have contributed to its success. Nowadays, however, that aesthetic seems to be working against the genre. Because so many of the seminal Brat Pack novels were published as paperback originals, they don’t have anywhere near the kind of value to book collectors that they might otherwise have accrued with time. I just bought a signed, first edition, first printing of the Vintage Contemporaries trade paperback of Bright Lights, Big City for $37 and a signed first edition of Vintage’s American Psycho for $150. The first edition of Ellis’s book was meant to be published in hardback and, if it had been, signed copies of it would probably cost a grand or more these days. But the controversy that engulfed the book before it was even published prompted the publisher to drop the project. So, the first edition isn’t all that valuable to collectors, which may encourage the (unfair) notion that the novel itself isn’t all that worthwhile.

Even the hardbacks can be remarkably inexpensive. I just purchased a signed hardback first edition of Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York, a seminal Brat Pack work, for $35. My signed first-edition hardbacks of McInerney’s Story of My Life and The Last of the Savages set me back $13.95 and $19.95, respectively. You don’t have to be a yuppie financial analyst to know that those books haven’t appreciated in monetary value. Time will tell if their cultural value ever appreciates. Currently, the literary Brat Pack seem to be very under-appreciated, but I suspect that someday they will enjoy a renaissance of some kind.

Although American Psycho and, to some extent, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History are now much better known than Bright Lights, Big City, McInerney’s debut remains an important American literary work. It was sharp and timely and—most important of all—it was first, introducing its readers to a new social phenomenon and milieu that became emblematic of the decade in which it was written. Only a tiny handful of American novels have been written in second person, present tense, and many critics dismissed this stylistic choice as a gimmick at the time, but it did somehow capture the eternal nowness of cocaine-fuelled yuppie life in New York City during the Reagan era. The book turns forty this year. It’s a pity that nobody seems to be celebrating.