Podcast

Podcast #256: Unreliable Sources

Iona Italia talks to Jack Despain Zhou (aka Tracing Woodgrains) about the decline of standards at Wikipedia as a result of the obsessive efforts of ideologically motivated editors.

Introduction: My guest this week is Jack Despain Zhou, also known by his alias Tracing Woodgrains. I first encountered Jack’s work when he was a research assistant on Jesse Singal and Katie Herzog’s excellent podcast Blocked and Reported.

Now, he is an independent writer and law student. In this conversation, we focus on the shenanigans at Wikipedia that are turning that formerly authoritative fount of crowdsourced wisdom into an unreliable, biased, and partisan site. The basis for our discussion is Jack’s detailed article on the topic, “Reliable Sources, How Wikipedia Admin David Gerard Launders His Grudges into the Public Record: A Love Story,” which was published on his Substack, which you can find under tracingwoodgrains.com. I hope you enjoy my conversation with Jack Despain Zhou.

Iona Italia: (00:42.094) Welcome, Jack.

Jack Despain Zhou: (00:44.167) Thank you, fantastic to be here.

II: (00:46.698) It’s a great pleasure to have you here—even though I continue to be annoyed with you for not writing for Quillette. You need to write for us!

JDZ: (00:53.903) I know, I know, I know. If it’s any comfort, I’ve had outreach from a lot of different people and each time I’ve been like, yeah, I’d love to and I’ll get to it maybe after I get to all these other things that like II: wants me to do and all this. just, the reality is when I write, it is because I have this pressing urge to write something at that moment. And every time I try to like harness it and sit down and say, yes, I have a schedule.

I have these articles. You know, I have right now a backlog of 20–30 articles that I would love to sit down and write and I just don’t. So, one day.

II: (01:31.962) Well, I’m really glad to hear that you are so much in demand because I have been extremely impressed by your work for a few years now, since you were doing the research for the Blocked and Reported podcast, Jesse Singal and Katie Herzog’s podcast, to which I’m also a subscriber. I’ll put a link in the show notes there. And I have just noted that you are exceptionally meticulous, autistically meticulous, and I mean that as a compliment.

And also, there is an extreme assumption of good faith and a genuine interest in ideas, which feels to me like the opposite of the problems that we’re going to discuss later in this podcast, which is people who are interested in ideas mostly as... who are interested mostly in the people behind the ideas and what they can pin on them, how they can discredit the ideas by delving into and getting dirt on the people. I think that’s a major recurring theme here. And that is the absolute opposite of what you do, which is a very clear focus on the ideas themselves and a real celebration of freedom of thought. I’m a fan.

JDZ: Well, I appreciate that. Those are definitely values that I try to express in my work, and it’s always gratifying when I hear that I live up to them to one extent or another. I do try.

II: Yes, I’m glad to see that your work is becoming better known, you’re becoming more popular and that is heartening and very much needed. We just need to clone you now one million times. And I’m sure, with your intelligence, you can be onto that. You can get that done.

JDZ: (03:35.239) Yeah, I’ve actually joked … especially with the rise of this recent AI and, you know, I say ‘joke’ and it will become, I think, less and less of a joke as time goes on, that I will be delighted when the AI becomes good enough to take my corpus and just write more of what I have. If it’s a cheap knockoff of me, that’s whatever, but if I could actually get something to sit down and write all the things that I intend to write and have it actually be my voice and my thoughts being expressed through something.

I would welcome a team of clones, if they’re robot clones, if they’re whatever, I would absolutely take joy in being the director of a team of … here are all of my thoughts. I have plenty to say, much more to say than I actually do say most of the time.

II: (04:21.52) So, we’re going to talk today about Wikipedia and the way that Wikipedia works behind the scenes, which is something of which I had absolutely no awareness before reading your article, and why it is so bad. Maybe I’ll start by citing a couple of examples of places where people have noticed how unreliable Wikipedia can be when the topic under discussion is controversial in some way, and in particular where there is a progressive orthodox view and a different view. I won’t even call it the “dissident” or “heterodox” view because it could be the view of the most people, but it’s not the view of the most online progressive types.

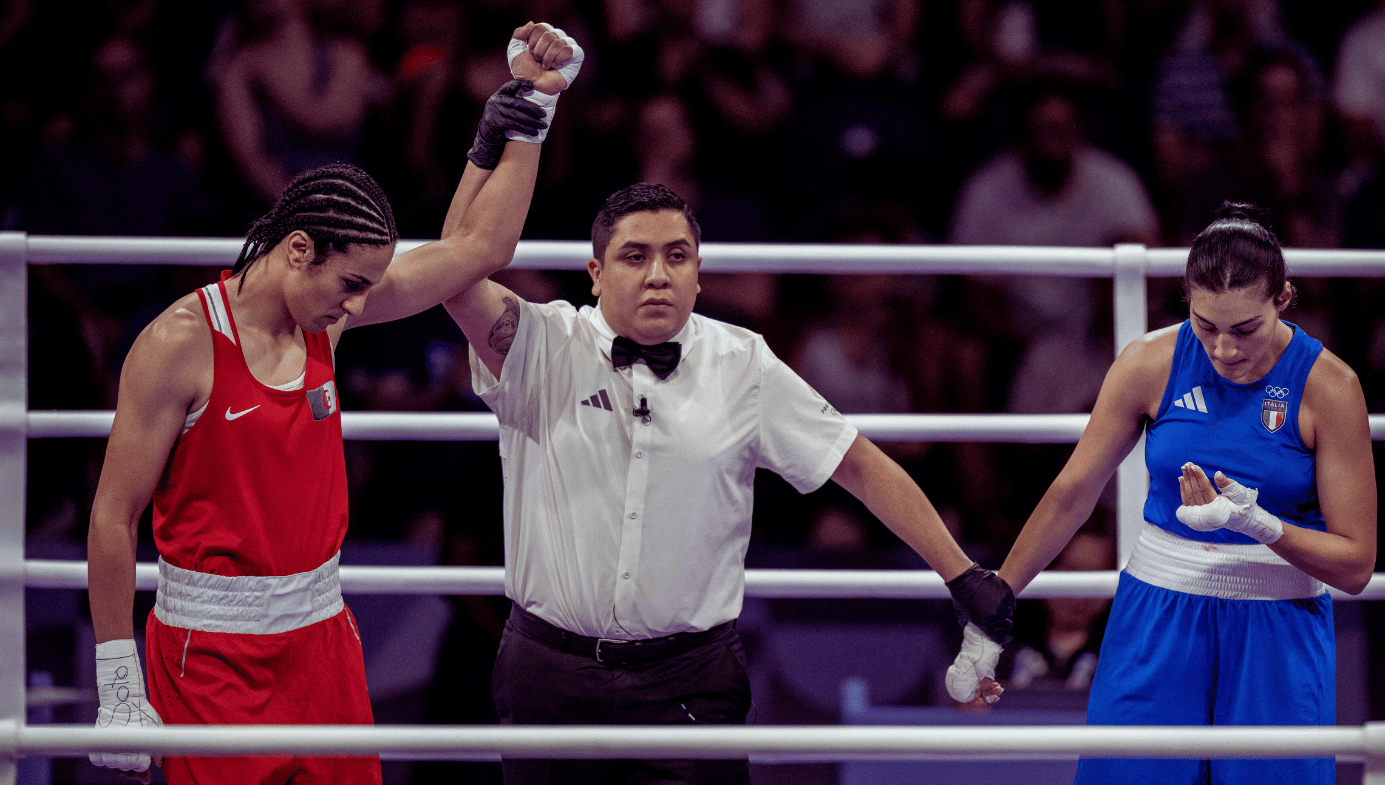

When there is a conflict like that, it seems that that’s where Wikipedia articles … that a couple of examples that I’ve seen recently seem the most striking in their inaccuracy. One that you highlighted was the recent controversy regarding the Algerian boxer, Imane Khalif, who is almost certainly a person born male, wrongly identified as a female at birth because of the unusual, atypical formation of her genitalia, which has to do with a specific disorder of sexual development, from which she almost certainly suffers. And we’ve written an explainer in Quillette about that, which I’ll put in the show notes as well.

But the Wikipedia article manages to just dismiss all of that and in a very mendacious way. Do you want to say a little bit more explaining that and how that works?

grateful that Wikipedia can always be trusted to provide a neutral overview of what Reliable Sources say about ongoing controversies pic.twitter.com/1Ghbdw7Xgs

— TracingWoodgrains (@tracewoodgrains) August 14, 2024

JDZ: (06:45.501) Yeah, absolutely. So the Wikipedia article on Imane Khelif is extremely careful in its wording and its phrasing and its presentation. And every word of it has been fought over, has been wrestled over by people who have very explicit motivations to paint a specific narrative. And the specific narrative that they want to paint is that this is a female boxer, who has been subject to waves of misinformation and harassment about her gender that has led to all sorts of negative consequences and that there is nothing whatsoever to the idea that there is anything beyond normal XX female with all of it.

Now for me, I have never really cared about... I’ve never really felt like women’s sports is my fight, personally. It’s not something that I pretend to be an expert in. It’s not something that I pretend to have a lot of a stake in. And this fight in particular is one that seemed … it’s something that only crossed my radar because it’s the sort of thing that a lot of people were fighting about. But looking at the Wikipedia page, what you would see is you would have medical reports saying this woman is intersex or her trainer saying she has something odd chromosomally, and independent people saying, “We’ve seen these medical reports, and yes, these labs indicate that she is most likely intersex,” or “These labs indicate that she is intersex.” And every time these things would come up, editors on the Wikipedia page would go onto the talk page and would explain via one rule or another, or via their interpretations of one rule or another: “This is why this thing is inadmissible”; “This is why this thing is inadmissible”; “This is why this thing is inadmissible.”

There are some times it becomes observed to the point of even actively trying to stick known false things on there because they say the sourcing isn’t where they want it to be with that. So, for example, people decided that it would be helpful to them to frame it as this Russian-led organisation trying to help Russian people. And what they claimed from it is that there was a previously undefeated Russian boxer that she had gone up against. And it was only after she defeated this boxer that they challenged her eligibility. And if you dive into it—and people did dive into it; people pointed out, “Look, this boxer wasn’t undefeated.” There were some defeats that weren’t on the records that these people were looking at and defeats that mainstream Western organisations who don’t actually follow Algerian boxes very carefully would have no particular reason to know about, but that were clearly in the record and people showed them and other people responded, “Well, look, these aren’t … this is original research, if you try to bring these defeats in” was their excuse. And their response to it was not, “Therefore we should leave this information that we know is false off,” but no, “We can keep this information that we know is false on until you can prove to us that one of the sources that we have to accept says this thing.” And it strikes me as a certain game for some people, where the goal is not we want to catalogue adequate information about this subject, but we have a particular vision in mind of the frame we want to put around this subject. And if someone wants to contest that vision, we have a set of rules that we are aware of that we will drag them through until either they give up and go away or until they have to escalate to someone higher than us. No matter what, we will not concede. We will not work together in a spirit of collaboration. We have a goal and the goal is to keep the bad people and the bad ideas away from this article by any means necessary. So that’s what happened with that article and that’s what happens with quite a few.

II: (10:51.908) Yeah, I noticed. One particularly annoying thing was that the article refers to misinformation about the boxer. And I can see in those internal Wikipedia comments, other editors commenting that there’s no reason to characterise this as misinformation because she almost certainly did have a disorder of sexual development. One of the editors defends the charge of misinformation on the grounds that there was misinformation that she was trans, and she is not trans. And that is just such misleading … it’s not just nitpicking, but it’s very misleading nitpicking.

JDZ: (11:48.325) Right. Nobody, no neutral party looking at it would say, “Yes, this is a clear and accurate description of what happened; people going to it will get a clear understanding.” It’s seizing on, you could call it a technicality, but it’s not even really a technicality. It’s just seizing on one specific sub-point that is convenient to them, using it to the exclusion of all else, and coming up with reasons why that specific sub-point should dominate over other things that have, even according to Wikipedia’s rules, more coverage in mainstream sources, more coverage by supposedly neutral institutions, everything. Once people have these points, they will seize on them and they’ll say any excuse that they can. If it’s in a reliable source or a source that they would normally treat as reliable, they’ll look and say, “Well, is the specific individual publishing in this source, have they published anything else that we would call unreliable and therefore can we impeach them that way?” Or, “Is this source … can we find some other policy?” And yeah, it’s just a game of which policy can we find to defend what we wanted to do in the first place?

II: (13:26.968) So, your long piece, “Reliable Sources,” traces the internal workings of Wikipedia through one specific editor, the editor is Wikipedia admin David Gerard, and you talk about that piece as a “love story.” You subtitled it “A Love Story.” Having read the piece now twice, I’m still not certain what you mean when you call it “a love story.” Can you maybe begin there?

JDZ: (14:11.283) Yeah, absolutely. You know, I had been aware of David Gerard for a long time before I wrote that article. And in some of the communities I spent time in, most everyone or a lot of people who had been around for a while were aware of him one way or another as just this reliable bad faith critic, this reliable haunt of these spaces who would every once in a while pay attention and point and laugh at one thing or another. And I had always seen him in that light—as just someone who had always been this bitter, cantankerous … bad faith troll type of person, someone who just goes and attacks without looking for any sort of conversation, without looking for any sort of common ground, anything like that, who just wants to cause trouble for people and just wants to mock people and just wants to spend all his time online watching things he hates. That’s the vision I had of him. So, when I started to really dig into his history for the article, it surprised me to see that that was not in any sense what I saw throughout his entire history. What I saw instead was someone who had been on the internet from the very, very early days and who had really been in love with—and this is where the “Love Story” subtitle comes from—had really been in love with what he saw as the ideals of the internet and what he saw as the culture of the internet from very early days. I saw someone who found many of the same communities I found and had much the same reaction I had to many of those communities, at least at first, before one thing or another, and I tracked the specific things in the article that set him off and turned him sour against the things he had loved.

I saw as I traced his history, this path starting from idealism and dreaming about the potential of the internet and dreaming about the culture that it would all pull forward into just fading into more and more … tracing really the whole split that has characterised internet culture since about 2012, 2013, from what he had loved of this unified internet culture before that, that was this sort of libertarian-ish, socialist-ish hacker culture, tech bro ethos, you can list a lot of these things, to what has become a more starkly polarised, crudely speaking, woke versus anti-woke culture. And he had really loved that first culture. And then I think felt blindsided by people from within that culture suddenly disagreeing with him on certain cultural issues. And ultimately, turning that same love that he had initially had towards it all to bitterness towards the people who had taken it from him, as it were, towards looking to what can he say and do against all of these forces that had changed something he had loved. And this is me trying to step in his shoes with it and explain. But yeah, as I tracked his history with the internet, with Wikipedia and with the groups he catalogued specifically, my overwhelming sense was that he had been this starry-eyed idealist in many ways who had fallen in love with it and then fallen out of love with it and acted in the end like a spurned ex-lover.

II: (17:47.118) And in many ways his early story parallels your early story because you also fell in love with the internet, right? You also found there a unique space in which to explore ideas?

JDZ: (18:03.965) Sort of. I would say my early internet history and even now my internet history has always been much more conflicted emotionally than Gerard’s straightforward internet is his tribe. And the reason is that I grew up Mormon and being a Mormon teenager on the internet in many ways is not a fun experience.

I grew up in suburban Utah County, with socially conservative values and believing in this religion and believing that basically everyone believed in this religion. It took until I was ten or eleven before I started realising, hold on, a majority of the world is not Mormon. And so when I hopped online, on the one hand, early on, I’m realising all the potential for it. Suddenly I’m realising here are people who share my interests. Here are other kids I can talk about Pokemon with or can talk about math with or can talk about all my nerdy hobbies with. On the other hand, if I ever try to share my opinion on a social issue or something, if you go back and look at … and it’s funny because I can, having spent enough time on the internet, I can go back and look at my early history. You can find me going on anti-gay rants on a Pokemon forum when I was thirteen years old. Which, for some reason, people didn’t respond well to that. I can’t imagine why.

The upshot of it is that I experienced from a very early age this tension where I recognised this unified internet culture. I recognised the set of unified internet values that Gerard and people like him had built. This fascinating world and this scary world and this for me many times combative world that didn’t really understand and didn’t really trust my values and that I understood some of it and trusted some of it, but felt at odds with other parts of it. So for me, it was always a hopelessly conflicted experience. Whereas for him, he had much more a straightforward acclamation to and love of the whole thing, which I think is what made it much more jarring for him. Whereas for me, when internet culture split, my impression of the split in internet culture, which came as I was coming of age was basically, okay, now a lot of other people who were in this sort of edgy atheist cohort are starting to realise what it felt like to be on the outs of internet culture and they don’t like it. But it felt very familiar to me at that time. I was like, yeah, this is what my experience online has been.

II: (20:43.032) One of the things that you defend really strongly in your article and elsewhere is an open forum for discussion, where you are tolerant of conversation with people with a very wide range of views, even including people whose views you might find quite abhorrent. And some of that, I guess, came from your own experience of places where you did feel more welcome to state your views, even though there was disagreement between you and the people you were talking to. Do you want to talk a little bit about your history with Less Wrong and the Rationalists? And then maybe let’s go to David Gerard’s history with them.