Podcast

Podcast #251: Tracing the Rise of Radicalised Anti-Zionism on American Campuses

Quillette podcast host Jonathan Kay speaks with author Paul Berman about the lingering influence of ‘Black Power’ advocate Stokely Carmichael, who once infamously claimed that ‘the only good Zionist is a dead Zionist.’

A video version of this podcast.

Jonathan Kay: Welcome to the Quillette podcast. I’m your host, Jonathan Kay, a senior editor at Quillette. Quillette is where free thought lives. We are an independent, grassroots platform for heterodox ideas and fearless commentary. If you’d like to support the podcast, you can do so by going to Quillette.com and becoming a paid subscriber. This subscription will also give you access to all our articles and early access to Quillette social events.

And today, we’re going to be talking about anti-Zionism with a very special guest, Paul Berman, author of the acclaimed New York Times bestseller Terror and Liberalism, as well as The Flight of the Intellectuals, A Tale of Two Utopias, and Power and the Idealists.

He is also the author of a widely read Liberties article, recently published by Quillette, entitled, A Stupid Cartoon and the University Ideology: Frantz Fanon, Stokely Carmichael, and the Roots of the Uproar over Zionism.

Okay, so I often cover a lot of ground in these podcasts, but this episode is particularly wide ranging, so I’m going to do my best to set the stage properly in this introduction.

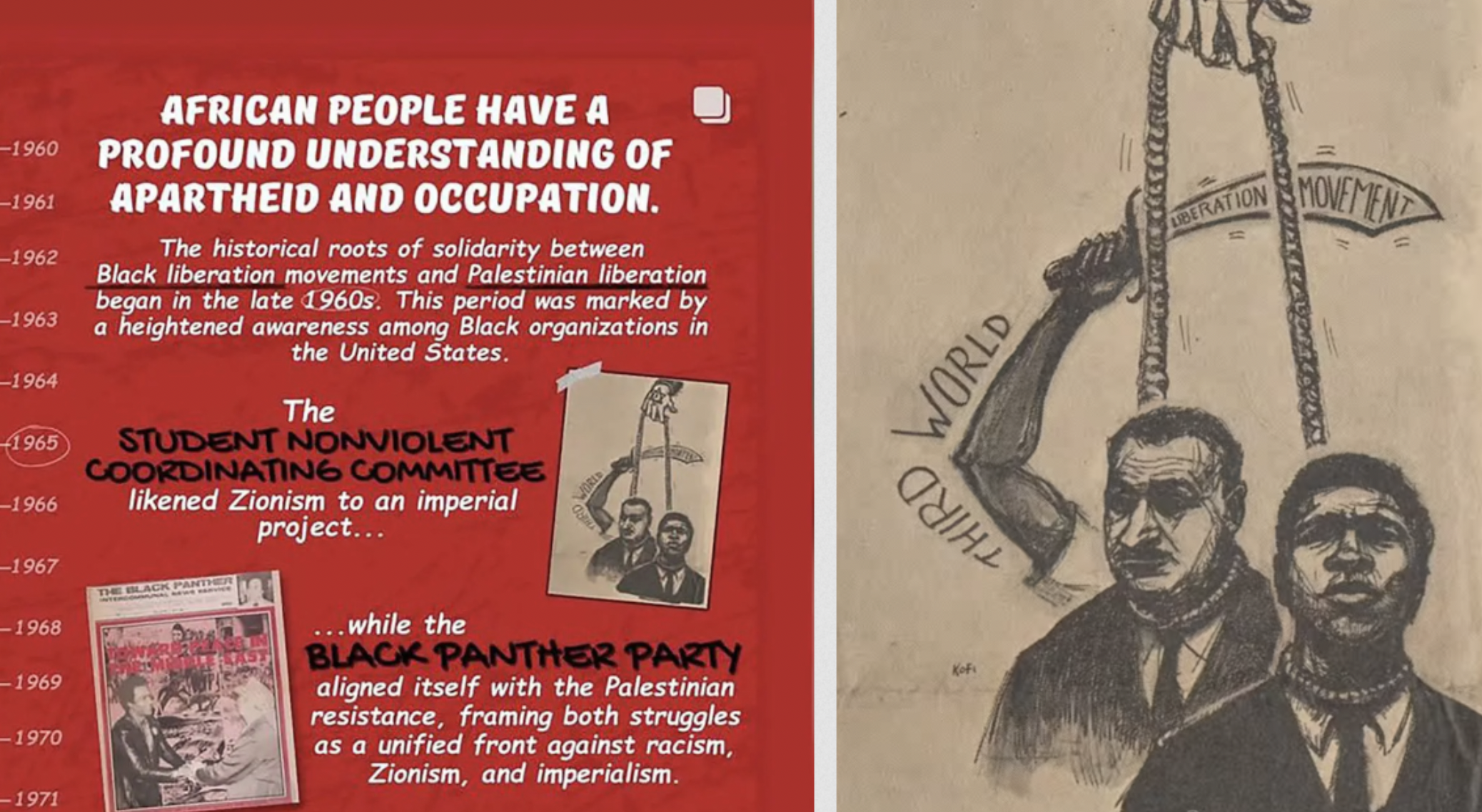

And the best place to start is with that aforementioned cartoon referenced in the title to Berman’s Quillette article. That cartoon was contained in an infographic published on Instagram back in February by two student organisations at Harvard University—the Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee and the African and African-American Resistance Organization with the support of a third organisation called Harvard Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine

The cartoon was supposed to show and acclaim the historical origins of African-American political solidarity with the Palestinian cause. But instead, it attracted accusations of antisemitism. And when I describe the cartoon, you will understand why. The image showed Blacks and Arabs being jointly oppressed by their common enemy, the Jew—specifically, a Black man and an Arab man with nooses draped around their necks. Holding the nooses and ready to give those ropes a yank was a hand bearing a Star of David tattoo encasing a dollar sign.

There were also other artistic details, such as an outstretched arm brandishing a machete, with the arm and machete labeled, “Third World Liberation Movement,” ready to slice the ropes. As Berman notes in his article, the cartoon was a “lurid melodrama of victimhood,” one that channelled some fairly obvious antisemitic imagery.

I will spare you the denouement of this Harvard scandal, which featured some half-hearted apologies from the groups that had posted this offensive image on Instagram. What’s of more interest to Berman is the source of this idea that Jews—or Zionists, if you prefer—are not only persecuting Palestinian Arabs, but also black people, in America and everywhere else.

Why, exactly, are the interests of these two groups interconnected, except by generalised rhetorical flourishes of the type associated with the so-called Third World Liberation Movement? As we will see, Berman answers that question by discussing three main figures, including Frantz Fanon, the French Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist whose famous books, including Black Skin, White Masks, followed a decade later by Wretched of the Earth, became central to the emergence of the anticolonial and pan-African movements.

Berman also discusses famed French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, whose work greatly influenced Fanon’s thinking, and who wrote an infamously inflammatory introduction to Wretched of the Earth. Most importantly, Berman discusses Stokely Carmichael, a key leader in the growth of the Black Power movement in the 1960s, as well as a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, sometimes called SNCC.

This is a subject Berman knows well, as he himself was once, by his own description, a student radical and protester with SNCC during his college years at Columbia University. As Berman relates, it was Carmichael who turned SNCC into an ardently anti-Zionist organisation, and who once infamously said, “the only good Zionist is a dead Zionist”—words that have an unsettling echo to some of the rhetoric we’ve heard on US college campuses over the last year.

Paul Berman spoke to me last week from his home in New York City. Here’s a recording of our interview.

Paul, thank you so much for joining the Quillette podcast. There’s a line in your article that really jumps out at me, where you talk about anti-Zionism as “the supreme moral prestige of the moment.” Could you explain what you mean by that phrase?

Paul Berman: The people who claim an anti-Zionist position claim it with an astonishing and dismaying degree of self-assurance, and the absurdity or meretricious quality of anybody who argues against it.

Jonathan Kay: You emphasise that this isn’t an ordinary anti-colonialist movement. It’s presented as the defining anti-colonialist movement. And there’s almost a certain apocalyptic quality to it… that somehow, if we win this struggle, then all anti-colonial struggles will be won. There’s something overarching, almost messianic about it.

Paul Berman: It is absolutely different in kind. It claims to be the supreme anti-colonialist argument, which is already a very strange argument to make. Zionism is not colonialism. So we’re dealing with an error, which is transformed into a supreme error, as you say, because the anti-Zionist position is regarded as the key to all of the sufferings around the world. So this is very bizarre.