Best of Areo Magazine

Answers to 12 Bad Anti-Free Speech Arguments

How to effectively counter some perennial arguments against free speech.

Editor’s Note: The following essay first appeared in Areo Magazine in May 2021 and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

In a podcast interview with Greg Lukianoff earlier that year, I expressed my frustration at being repeatedly confronted with the same hackneyed arguments against free speech. In response, Lukianoff wrote an article outlining some of these arguments and systematically debunking them one by one.

He continued the list in a multi-part series of essays on his blog, The Eternally Radical Idea, with the assistance of former president of the ACLU and free speech expert Nadine Strossen.

In Lukianoff’s new book, The Cancelling of the American Mind (Oct 2023), co-authored with Rikki Schlott, he traces the development of threats to free speech in the US in the intervening period since the publication of this piece and demonstrates that the culture has become, if anything, more hostile to freedom of speech than before.

—Iona Italia

Those of us who defend free speech often find ourselves combating the same bad arguments in favour of censorship over and over again. In this article, I will suggest responses to some of the most common arguments against freedom of speech, and, where possible, will intersperse links to articles that develop these arguments further.

Assertion 1: Free speech was created under the false notion that words and violence are distinct, but we now know that certain speech is more akin to violence.

Answer: Speech equals violence isn’t a new idea. It’s a very old—and very bad—idea.

On campus, I often run into people—not only students, but professors—who seem to think they’re the first to notice that the speech/violence distinction is a social construct. They conclude that this means it’s an arbitrary distinction—and that, since it’s arbitrary, the line can be put where they please. (Conveniently, they draw the line based on their personal views: if it’s speech that they happen to hate, then it just might be violence.) But, ironically, the whole point of freedom of speech, from its beginning, has been to enable people to sort things out without resorting to violence. A quotation often attributed to Sigmund Freud (which he attributed to another writer) conveys this: “The first human being who hurled an insult instead of a stone was the founder of civilisation.”

Yes, a strong distinction between the expression of opinion and violence is a social construct, but it’s one of the best social constructs for peaceful coexistence, innovation, and progress that’s ever been invented. Redefining the expression of opinion as violence is a formula for a chain reaction of endless violence, repression and regression.

Assertion 2: Free speech rests on the faulty notion that words are harmless.

Answer: No, it doesn’t. If free speech was not powerful there would be no need either to protect or ban it. It’s not surprising that free speech can be harsh, since it’s meant as a replacement for actual violence.

Historically, freedom of speech has been justified as part of a system for resolving disputes without resort to actual violence. Acceptance of freedom of speech is a way to live with genuine conflict among points of view (which has always existed) without resorting to coercive force.

I’ve made this point at so many times in my career, in so many different ways, that someone made a graphic about the way I once put it on a TV show.

It’s not surprising that free speech in a democracy can be very heated, when that protection covers people’s most sincerely held religious beliefs and their opinions about matters of life and death.

As I argue in my 2014 book, Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate:

The idea that we should campaign against hurtful speech among adults arises from a failure to understand that free speech is our chosen method of resolving disagreements, using words rather than weapons. Open debate is our enlightened means of determining nothing less than how we order our society, what is true and what is false, what wars we should fight, what policies we should pass, whom we should put behind bars for the rest of their lives, and who gets to control our government. This is a deadly serious business.

Being a citizen in a democratic republic is supposed to be challenging; it’s supposed to ask something of its citizens. It requires a certain minimal toughness—and commitment to self-governing—to become informed about difficult issues and to argue, organize and vote accordingly. As the Supreme Court observed in 1949, in Terminiello v. Chicago, speech “may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.”

The only model that asks nothing of its citizens in terms of learning, autonomy and decision-making is the authoritarian one. By arguing that freedom from speech is often more important than freedom of speech, advocates unwittingly embrace the nineteenth-century (anti-)speech justification for czarist power: the idea that the Russian peasant has the best kind of freedom, the freedom from the burden of freedom itself (because it surely is a burden).

For more on the history of censorship through the ages, I highly recommend Eric Berkowitz’s 2021 book Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, from the Ancients to Fake News.

Assertion 3: Free speech is the tool of the powerful, not the powerless.

Answer: The powerful do well under virtually any system of government. They’re not the ones who need freedom of speech. Its purpose is precisely to protect minority opinions and those who are unpopular with powerful people.

For most of history, the rich and powerful were protected by their wealth and power. Then, when democracies first emerged, the majority set the laws, and, because of that, their majority positions were protected by law. You only need a separate concept of freedom of speech or a law like the First Amendment to protect people, ideas, and arguments that are not already otherwise protected by the right to vote or some other power.

The ones who enforce the rules, are, by definition, powerful. In a country with strong protections for freedom of speech, the powerful are barred from using the legal system to attack the powerless for their speech. If you empower the government to censor, you are giving the powerful more power. The idea that we can trust them to use that power to defend the powerless is not borne out by history. If you want to give whichever people are most powerful censorship tools to protect the marginalised, do you trust that they will use them well? Do you trust what a Biden administration would do with that power? If so, do you trust what a Trump administration would do with that power? A good intellectual exercise before passing a new law is to consider how your worst enemy would use that law—and thinking about that is even more important when imagining restrictions on free speech.

Assertion 4: The right to free speech means the government can’t arrest you for what you say; it still leaves other people free to kick you out.

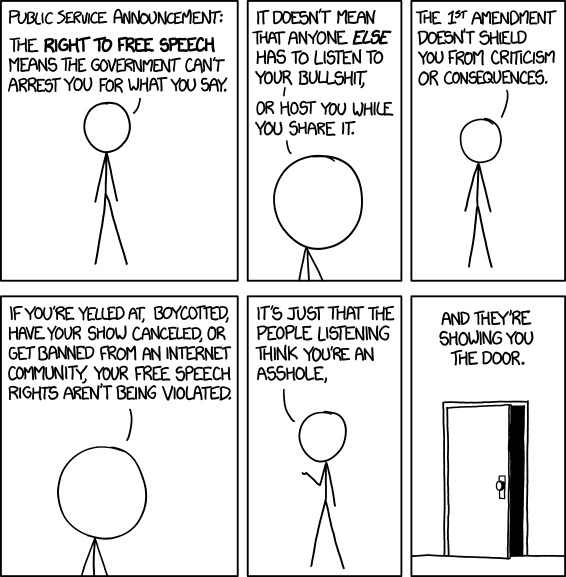

Answer: No, the popular xkcd cartoon below is wrong. The First Amendment limits what the government can do, but freedom of speech is something much bigger than that.

This cartoon is often used to dismiss free speech arguments, but it is wrong: it not only confuses First Amendment law with freedom of speech, it doesn’t even get the First Amendment right.

The concept of freedom of speech is a bigger, older and more expansive idea than its particular application in the First Amendment, even if we are talking about the US context alone. A belief in the importance of freedom of speech is what inspired the First Amendment; it’s what gave the First Amendment meaning, and what sustains it in the law. But a strong cultural commitment to freedom of speech is what maintains its practice in our institutions—from higher education, to reality TV, to pluralistic democracy itself. Freedom of speech includes small-l liberal values that were once expressed in common American idioms like “to each his own, everyone’s entitled to their opinion” and “it’s a free country.” These cultural values appear in legal opinions too; as Justice Robert H. Jackson noted in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, “Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.”

While the United States Constitution limits only governmental behaviour on its face, its application sometimes requires the government to protect you from being censored by other citizens. For example, the government has a duty to protect you from being attacked by a hostile mob that doesn’t like your ideas or having your public speech disrupted by a heckler’s veto.

The First Amendment also bars government officials from punishing your speech in many ways that don’t rise to the level of arresting you. To give just one example, since administrators at state colleges are government actors, they can’t tear your flyer from a public message board because they don’t like what it says.

A belief in free speech means you should be slow to label someone as utterly dismissible for their opinions. Of course you can kick an asshole out of your own house, but that’s very different from kicking a person out of an open society or a public forum. The xkcd cartoon is often used to let people off the hook from practicing the small-d democratic value of listening.

Assertion 5: But you can’t shout fire! in a crowded theatre.

Answer: Anyone who says “you can’t shout fire! in a crowded theatre” is showing that they don’t know much about the principles of free speech, or free speech law—or history.

This old canard, a favourite reference of censorship apologists, needs to be retired. It’s repeatedly and inappropriately used to justify speech limitations. People have been using this cliché as if it had some legal meaning, while First Amendment lawyers point out that it is, as Alan Dershowitz puts it, “a caricature of logical argumentation.” Ken White penned a brilliant and thorough takedown of this misconception. While his piece is no longer available online, you can find a thorough discussion of the arguments by Jerry Coyne here. Please read it before proclaiming that your least favourite language is analogous to “shouting fire in a crowded theatre.”

The phrase is a misquotation of an analogy made in a 1919 Supreme Court opinion that upheld the imprisonment of three people—a newspaper editor, a pamphlet publisher, and a public speaker—who argued that military conscription was wrong. The court said that anti-war speech in wartime is like “falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic,” and it justified the ban with a dubious analogy to the longstanding principle that the First Amendment doesn’t protect speech that incites people to physical violence. But the Supreme Court abandoned the logic of that case more than 50 years ago. That this trope originated as a justification for what has long since been deemed unconstitutional censorship reveals how useless it is as a measure of the limitations of rights. And yet, “the crowded theatre” cliché endures, as if it were some venerable legal principle.

The court’s objection, we should note, was only to “falsely shouting fire”: if there is, in fact, a fire in a crowded theatre, please let everyone know.

Assertion 6: The arguments for freedom of speech are outdated.

Answer: John Stuart Mill’s central arguments in On Liberty remain undefeated, including one of his strongest arguments in favour of freedom of speech—Mill’s trident—of which I have never heard a persuasive refutation.

Mill’s trident holds that, for any given belief, there are three options:

- You are wrong, in which case freedom of speech is essential to allow people to correct you.

- You are partially correct, in which case you need free speech and contrary viewpoints to help you get a more precise understanding of what the truth really is.

- You are 100% correct. In this unlikely event, you still need people to argue with you, to try to contradict you, and to try to prove you wrong. Why? Because if you never have to defend your points of view, there is a very good chance you don’t really understand them, and that you hold them the same way you would hold a prejudice or superstition. It’s only through arguing with contrary viewpoints that you come to understand why what you believe is true.

Assertion 7: Hate speech laws are important for reducing intolerance, even if there may be some examples of abuse.

Answer: Since the widespread passage of hate speech codes in Europe, religious and ethnic intolerance there has gone up. During the same period, ethnic and religious tolerance have improved in the United States.

At least a dozen Western European countries have hate speech laws, many of which run counter to their legal or historical commitments to free speech. But even though those laws have been on the books for years, by most measures Western Europe is less tolerant than the United States.

Western Europe as a whole scores 24% on the antisemitism index, meaning about 24% of the population harbours antisemitic attitudes, even though many of their hate speech laws explicitly prohibit Holocaust denial. In the United States, with no such laws, the antisemitism index is ranked at 10%.

If it were true that hate speech laws reduce intolerance, we would expect to see fewer hate crimes where such laws exist. Yet, in 2019, in the United States, there were 2.61 hate crimes per 100,000 people; in Denmark, there were 8.08 per 100,000 people; in Germany, 10.34; and in the United Kingdom, a whopping 157.67.

Nor has restricting hate speech prevented the spread of intolerance. In 1986, the UK passed a law against “words or behaviour … likely to stir up racial hatred”; yet, in the 1990s, racial tolerance decreased. Despite having hate speech laws since the 1980s, Germany is experiencing increased anti-Muslim bigotry and antisemitism. France passed its Gayssot Act outlawing Holocaust denial in 1990, yet as recently as 2019 it held a 17% antisemitism index score.

And I don’t just believe that cracking down on hate speech failed to decrease intolerance, I think there are solid grounds to believe that it helped increase it. After all, censorship doesn’t generally change people’s opinions, but it does make them more likely to talk only to those with whom they already agree. And what happens when people only talk to politically similar people? The well documented effect of group/political polarisation takes over, and the speaker, who may have moderated her belief when exposed to dissenting opinions, becomes more radicalised in the direction of her hatred, through the power of group polarisation.

Assertion 8: Free speech is nothing but a conservative talking point.

Answer: Free speech is neither a conservative nor liberal idea. It is an eternally radical idea.

In our hopelessly polarised societies, too many people begin by asking, “So, is free speech a conservative or progressive idea? Is it right-wing or left-wing?” If the answer is “left-wing,” throngs on the right assume it can be ignored. If the answer is “right-wing,” many on the left feel absolved from having to take it seriously. At various points—even in recent history—both major political parties in the United States have claimed to represent free speech at the same time as both have been extremely hostile to free speech.

True support for free expression—especially extreme political speech with which you disagree—is a rare and, indeed, historically radical idea. I think this point is so important that I even named my blog The Eternally Radical Idea.

Assertion 9: Restrictions on free speech are OK if they are made in the name of civility.

Answer: In certain settings, they can be reasonable, but, generally, what is “civil” is defined by the powerful or the majority. And they tend to see any speech with which they simply disagree as “uncivil,” while seeing any uncivil speech with which they agree as “righteous rage.”

Assertion 10: You need speech restrictions to preserve cultural diversity.

Answer: Few ideas are more culturally diverse than what counts as propriety, or what constitutes correct or acceptable speech. These ideas are different from country to country, from year to year, for men and women, and especially across class lines. Indeed, preserving diversity in an environment with many cultures requires, rather than forbids, a high tolerance for speech that adheres to different norms of propriety.

Assertion 11: Free speech is an outdated idea; it’s time for new thinking.

Answer: Censorship is a far older idea, as old as our species; free speech is comparatively the new kid on the block. As Nat Hentoff once wrote, quoting former Los Angeles Times editor Phil Kerby: “Censorship is the strongest drive in human nature; sex is a weak second.” For a more detailed version of this argument, see Hentoff’s 1992 book Free Speech For Me—But Not For Thee: How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other.

Assertion 12: I believe in free speech, but not for blasphemy.

Answer: You cannot claim to believe in free speech and at the same time carve out an exception for blasphemy. That’s the whole ball game. Ideas of freedom of speech came about precisely to address the tendency to label unorthodox views as heretical.

Conclusion

Free speech is valuable, first and foremost, because, without it, there is no way to know the world as it actually is. Understanding human perceptions, even incorrect ones, is always of scientific or scholarly value, and, in a democracy, it is essential to know what people really believe. This is my “pure informational theory of freedom of speech.” To think that, without openness, we can know what people really believe is not only hubris, but magical thinking. The process of coming to know the world as it is is much more arduous than we usually appreciate. It starts with this: recognise that you are probably wrong about any number of things, exercise genuine curiosity about everything (including each other), and always remember that it is better to know the world as it really is—and that the process of finding that out never ends.

Author’s note: I would like to thank Adam Goldstein, Sean Stevens, Ryne Weiss and Komi German from FIRE for helping put this together, and especially for gathering the comparative hate crime data from EU countries.