My only Mecca was, is, and shall always be Howard University.

~Ta-Nehisi Coates

Veritas et Utilitas (Truth and Service)

~Howard University motto

I. “A Cold-Blooded Murder”

Ta-Nehisi Coates has told the story of Prince Jones’s death on September 1st, 2000, at the hands of a Prince George’s County undercover officer, many times in various formats over the past two decades. The most notable account of this incident appears in his National Book Award-winning 2015 memoir, Between the World and Me. Sometimes “they” killed Jones, his spirited and charismatic Howard University classmate, even though the officer and Jones were the only two people present during the early-morning encounter and all 16 shots, five of which struck Jones in the back, were fired by that officer. Sometimes, Coates acknowledges that the officer, like Jones, was black. Other times, he remains silent on that point, allowing readers and listeners to assume what they will—that the officer is white, surely, and that the killing was an early harbinger of a familiar contemporary storyline evoked by the names Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner. Still other times, as in his memoir, Coates finesses the issue of the officer’s race until he’s midway through the story, then downplays the importance of that detail.

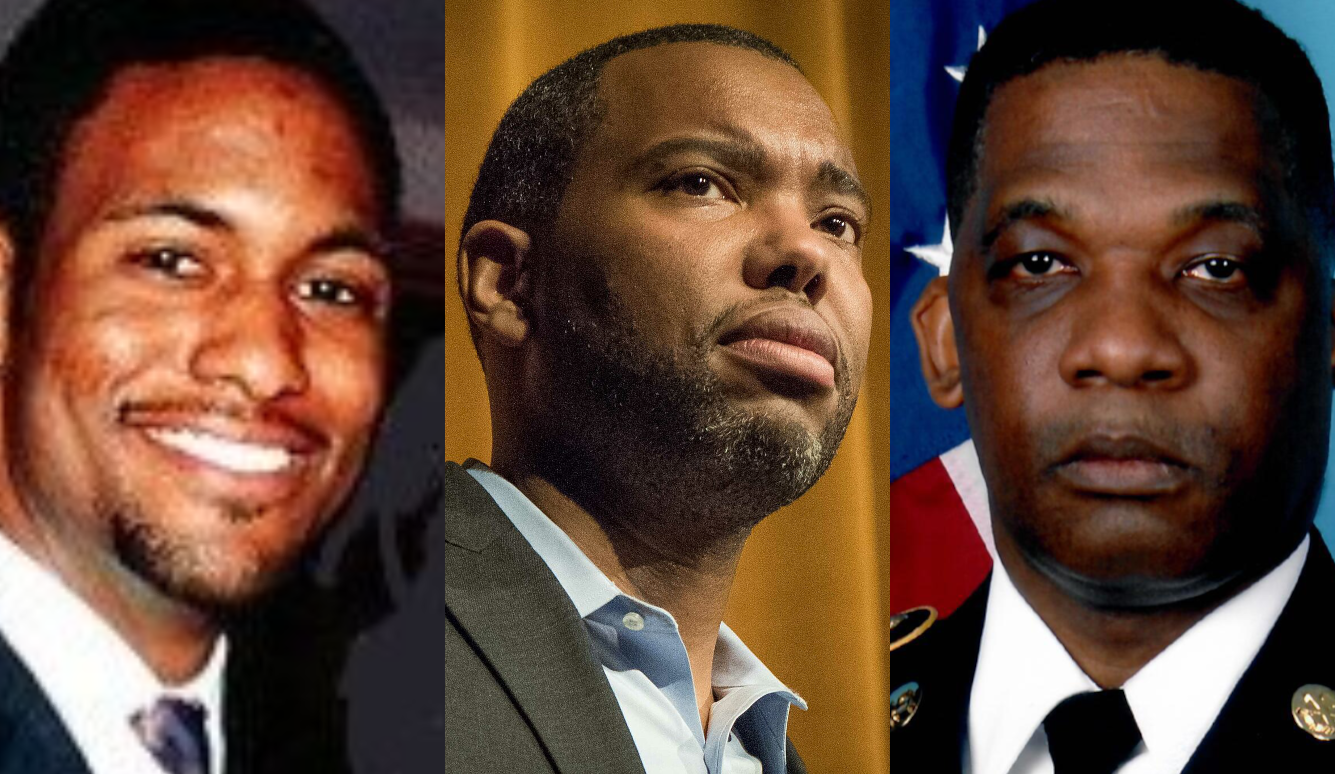

As stricken as Coates was by Jones’s death, as familiar as he is with the particulars of the case, as intent as he is on bearing witness to Jones’s loss in his writings, speeches, and interviews, there are two facts about the black officer who shot and killed his friend that Coates intentionally mutes. The first is the officer’s name: Carlton B. Jones. (The two Jones men are unrelated.) Coates has publicly named the officer only a handful of times: in a 2001 essay for Washington Monthly; in a brief 2008 note in the Atlantic; and in a 2012 essay for the same magazine titled, “Fear of a Black President,” later republished in We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy (2017).

Carlton Jones remains unnamed in Between the World and Me and in the major interviews—for “Fresh Air,” “All Things Considered,” and with Charlie Rose—that Coates gave while he was promoting his book. This elision makes sense. Refusing to name the officer who killed his friend is a principled way of refusing to acknowledge the officer’s humanity. Irrespective of his race, he’s just a cog in a malevolent system that has “black bodies” in its sights: distilled to its essence, that is the argument leveled by Between the World and Me. “A cold-blooded murder” is what Coates called Prince Jones’s death in his 2001 Washington Monthly essay, but by the time he published his memoir in 2015, he had shifted his emphasis. “[I]n some inchoate form,” he wrote then, “I knew that Prince was not killed by a single officer so much as he was murdered by his country and all the fears that have marked it from birth.”

The second and more salient fact about the officer that Coates leaves out of the story altogether—avoiding it with what appears to be scrupulous care—is that Carlton Jones, too, was a Howard man: a fellow habitué of “the Mecca,” as Coates termed the storied dreamscape of black empowerment that was his and Prince Jones’s alma mater. Carlton, who spent a year-and-a-half on campus (1988–90) after prepping at a military college, had already left Howard by the time Prince (1992–2000) and Ta-Nehisi (1993–99) arrived. None of the three young men ended up graduating. But Carlton Jones—the supposedly rogue investigator who murdered Coates’s friend and muse—was indeed Coates’s secret sharer, if not quite his classmate, at the nation’s preeminent HBCU.

Noted in passing by the Los Angeles Times (2000) and People magazine (2001), this fact has been a matter of public record since at least August 2002, when the Washington Post included it in Craig Whitlock’s deeply reported re-examination of the case. But it has been expunged from public memory, chiefly because, although Coates has praised the Post’s coverage, he has refused to grant it quarter in the version of events he has created—a narrative shaped to the purpose of indicting the antiblack violence he locates at the heart of American whiteness.

Coates’s evasion, his thoroughgoing suppression of this uncomfortable truth, deserves more critical attention than it has received to date, which is none. What happens to Coates’s indictment of America and its “dreamers”—his term for morally unconscious whites who benefit from the black-body-devouring charnel house of a nation they inhabit—if, rather than anonymizing and silencing Carlton Jones, banishing him from Howard’s Mecca, we grant him a voice? What sort of tragedy, then, does the death of Prince Jones become?

It becomes, first and foremost, the story of two troubled but ambitious Howard men, both intent on forging careers in the US military, who encountered each other on a suburban Virginia street late one night, each man in his own vehicle, under circumstances that made mutual recognition impossible. The precise details of what occurred that night remain in question. But we know far more now than we did in the days and weeks after Prince Jones’s death, thanks in part to evidence introduced during the 2006 civil trial; far more in the way of granular detail than Coates, determined to indict America and its dreamers, was interested in arbitrating.

Carlton Jones provided no fewer than seven separate accounts of that encounter in depositions, statements, and courtroom testimony between 2000 and 2006. From these, we also know that the officer’s story of a surveillance operation gone awry evolved in subtle but important ways before hardening into the set piece it later became—a set piece neither substantially rebutted nor wholly confirmed by physical and eyewitness evidence, but a story to which he and his attorneys stuck doggedly at trial, although his attorneys did their best to finesse certain problematic details in an effort to align it with eyewitness accounts.

We know, too, the grim details of the fatal shooting itself: 16 shots fired from a 9mm Beretta in what one expert witness estimated to be four seconds. Five of those shots struck Prince in the back. Was this a desperate act of justified self-defense, as Carlton maintained? Or was it an unjustified act—a “racist act,” Prince’s mother told Coates—of cold-blooded murder against a black man presumed to be guilty of something that would license such an excessive response from a Maryland cop with no police powers in this Virginia jurisdiction? Or does neither of those framings fully accord with the facts?

In Between the World and Me, Coates delivers his considered verdict on Prince’s death in a fashion that permits his friend neither agency nor culpability, even as it anonymizes Carlton Jones and enlarges him into a presumptively white They. “The killer,” Coates writes, “was the direct expression of all his country’s beliefs. ... [T]hey had destroyed [Prince’s] body, scorched his shoulders and arms, ripped open his back, mangled lung, kidney, and liver.”

But the killer, as Coates knew when he published these words in 2015, had a name, a history, and a claim of his own on the Mecca that Howard University had been for all three black men until that fateful night. It is important for Coates’s indictment of America that he depersonalize Carlton Jones in specific ways, suppressing acknowledgement of his blackness while refusing to name him or the fraternal connection they share:

Weeks wore on. Nauseating details slowly dribbled out. The officer was a known liar. A year earlier he had arrested a man on false evidence. Prosecutors had been forced to drop every case in which the officer was involved. The officer was demoted, restored, then put out on the street to continue his work. Now, through additional reports, a narrative began to take shape. The officer had been dressed like an undercover drug dealer. He’d been sent out to track a man whose build was five foot four and 250 pounds. We know from the coroner that Prince’s body was six foot three and 211 pounds. We know that the other man was apprehended later. The charges against him were dropped. None of this mattered. We know that his superiors sent this officer to follow Prince from Maryland, through Washington, D.C., and into Virginia, where the officer shot Prince several times. We know that the officer confronted Prince with his gun drawn and no badge. We know that the officer claims he shot because Prince tried to run him over with his jeep. We know that the authorities charged with investigating this shooting did very little to investigate the officer and did everything in their power to investigate Prince Jones. This investigation produced no information that would explain why Prince Jones would suddenly shift his ambitions from college to cop killing. This officer, given maximum power, bore minimum responsibility. He was charged with nothing. He was punished by no one. He was returned to his work.

Much of what Coates writes here is true, and some of it is damning. But not all of it is true. The truth, as will become clear, is more complicated than this grief-provoked and tendentious telling is willing to allow. The story of Carlton Jones and his deadly encounter with Prince Jones is a tragedy, but that fuller tragedy is not the story that Coates has chosen to give us.

Although the Prince George’s County police force was conspicuously brutal, earning a national reputation for murderous policing, much of it against black suspects, Corporal Jones was not a violent man. The night he killed Prince Jones was only the third time in six years on the force that he had fired his service weapon and the first time he’d actually hit anybody. My desire here, I should stress, is not to advocate on behalf of Carlton Jones. In the documentary evidence I amassed during 18 months of research, Jones emerges as a complex figure, and at key moments, an untrustworthy narrator; someone willing to mingle truth with lies and distortions, which is precisely what undercover cops do on the job to maintain their cover. I simply want to know what happened between those two Howard men, 32 and 25, when they encountered each other on Spring Terrace in Falls Church, Virginia, at 2:50am on September 1st, 2000.

II. The Student

“We believe that Prince Jones was stalked and murdered,” said Ted Williams, a former homicide investigator now acting as one of the attorneys representing Prince’s family, one week after his death. “[F]or those close to Prince Jones,” agreed Coates, “the police account is simply an attempt to cover up a cold-blooded murder.” Neither of these claims, stalking or cold-blooded murder, was true. But the claims, and the feelings that produced them, were understandable. An inexplicable death creates a breach in the social fabric. It precipitates questions, charges, and countercharges, explosions of rage and grief, a yearning for narrative closure.

Prince Jones, as Coates noted nine months after his death, was the 12th person shot by Prince George’s County police officers over the preceding 14 months. “Five of those 12 died. Two other men, who were not shot, died in police custody.” So yes, this killing could easily be folded into a narrative about out-of-control cops: “a higher rate of fatal shootings per officer than any other major city or county police force at the time,” according to the Washington Post’s 2001 multi-article investigation, and a department on which the DOJ would subsequently clamp down after a damning pattern-or-practice investigation. And yes, as journalists Jason Cherkis and Kevin Diaz noted, “In some respects, Prince Jones fits the typical P.G. County cop shooting-victim profile: a young minority male spotted in a bad neighborhood.”

But Prince was a Howard man, and a singular figure—not just in the eyes of Coates, who “had love for this boy,” but also among others who’d known him on campus and in the life he’d led before his arrival there. That distinction made a difference to much of what followed: the continuing coverage the story received in the Washington Post in the weeks following his death; the rapid arrival of the FBI and the initiation of a DOJ civil-rights investigation; the visit to Howard’s campus by presidential candidate Al Gore—“We must have action to stop racial profiling in the United States of America”—and Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder; the aggressive tenacity of Ted Williams and Gregory Lattimer, the attorneys hired by Prince’s mother, Dr. Mabel Jones, a Philadelphia radiologist.

Prince Jones was a child of relative privilege, albeit from a broken home, born in New Orleans and raised in rural Louisiana, where his father was the safety director for an oil-field service company. Jones and his mother—a Navy vet, a med school graduate, and the daughter of sharecroppers—relocated to Duncanville, Texas, just south of metro Dallas, when he was eight years old. There, he excelled academically and socially, earning admission into the Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science: the only black student in a class of 200, the prom king in his senior year.

One of his classmates called Prince “a perfect gentleman.” “If I were to pick a student who was most likely to be President of the United States,” a school administrator later offered, “I would choose Jones. He had that kind of charisma.” At Howard, which he entered in 1992 with two years’ worth of AP credit, he was a vegetarian who practiced tai chi, a tall and soft-spoken churchgoer majoring in human development and childhood education. He was so popular among his classmates that one of his roommates nicknamed him “Ferris Bueller.” He never used drugs, insisted his friends and family, and had no record of drug arrests in either the District or surrounding counties.

Prince’s intellectual gifts and popularity on campus were, however, shadowed by several countervailing dynamics—bad facts, a lawyer might call them, that complicate the portrait of a charismatic, ambitious, and self-disciplined young man on the move. First and most obvious was the fact that, as the fall 2000 term began, he still hadn’t graduated from Howard, eight years after arriving with AP credits in hand. He was an excellent student when focused, according to his academic advisor, but his attention wandered. He took Incompletes and semesters off; he worked part-time jobs. He’d had a rocky relationship with his most recent girlfriend, Candace Jackson, the mother of his 10-month-old daughter Nina. Over the preceding two years, according to the Washington Post, “police [had] investigated four domestic abuse complaints involving the couple. Although Jackson never pressed charges, she told police that they had repeatedly punched and kicked each other. During a fight when she was seven months pregnant, Jones struck her in the jaw and twice pushed her to the ground.”

“He tried to project the image of being at peace,” Coates told a journalist only three weeks after Prince’s death in a moment of candor at odds with the quasi-religious portrait of the Mecca’s martyr he would later evolve. “I always got the impression that he was really, really struggling with stuff. I never got the impression it was drugs. I thought it was personal life struggles.” Yet things were, or seemed to be, coming together for Prince as Howard’s fall term began. He planned to complete his degree in December and enter the US Navy’s Officer Candidate School on January 1st. He was working as a personal trainer at a Bally’s near DC, fit and happy by all appearances, and newly committed to his relationship with Jackson, who was now his fiancée. In recent months, his pastor had been counseling him on anger management.

On August 26th, 2000, only a few days before Prince Jones’s death, thousands assembled at the Lincoln Memorial as part of the March on Washington Against Police Brutality, nicknamed “Redeem the Dream” and intended to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the original March on Washington. Speakers at the event, which also highlighted the issue of racial profiling, included Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King III, the Rev. Al Sharpton, and Kwesi Mfumé, head of the sponsoring NAACP.

When Vice President Al Gore visited Howard three weeks later, calling for a moment of silence in Prince Jones’s honor and reaffirming his support for the National Hate Crimes Law, the campus mood was aggrieved. “[The students] are outraged,” said Nikkole Salter, vice president of the Howard Student Association. “It could have easily been any one of them.” Gore’s denunciation of police brutality, according to a student journalist from George Washington University, “received thunderous applause from the full auditorium.” The phrase “one of them” surfaced again, later in the story, when the student journalist spoke with Rob Cannaday, a veteran counselor in GWU’s Multicultural Student Services. According to Cannaday, many students were shocked when they learned that the officer who shot Prince Jones was black; they had assumed that he was white and that racial profiling was involved. “I think students tend to lean to Prince Jones’ (supporters’) version,” he said, “because he’s one of them.”

But the officer, too, was one of them: a Howard man. Nobody at Howard seemed to know this, because that fact never surfaced in news coverage—not until Craig Whitlock’s long Washington Post piece almost two years after Prince’s death. At that point it was ignored, falling out of public memory, because the people’s verdict on Carlton Jones had already been rendered. “[T]he officer has relinquished the right to be considered ‘a brother,’” Prince’s roommate declared, three weeks after Prince’s death.

This racial and institutional excommunication was followed, over the years and with Coates’s principled assistance, by the erasure of Carlton’s name and his enlargement into an inhuman monstrosity. “The killer,” Coates insists at various points in Between the World and Me, was “the direct expression of all his country’s beliefs,” “a force of nature, the helpless agent of our world’s physical laws,” and “the sword of the American citizenry.” “I could see no difference,” he adds, “between the officer who killed Prince Jones and the police who died [in the World Trade Center on 9/11], or the firefighters who died. They were not human to me.”

III. The Officer

So, who is Carlton B. Jones? A Howard man, yes, like Prince and Ta-Nehisi. Not an alum—none of the three was technically that—but a denizen of the Mecca nonetheless. But who is he? Or rather, who was he on the day his fate became forever entangled with that of the Howard man he killed and the Howard man who made it a point of honor to expunge him from the rolls of the righteous? Most of what we know about Jones emerged from the depositions and courtroom testimony he gave in response to various civil actions brought against him in his capacity as a police officer for Prince George’s County.

Jones, a native of Washington, DC, was born on May 10th, 1968, roughly one month equidistant from the sequential assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. (April 4th) and Robert F. Kennedy (June 5th). Several news accounts reference the fact, purportedly shared with his lawyer and savoring of a deliberate PR drop, that he had been inspired by King’s “vision of racial harmony” to choose law enforcement as a career. More directly relevant to his eventual posting as an undercover officer was the vision of Washington, DC, as an open-air drug market that he formed as a child growing up in the District. When asked by the attorney for Prince Jones’s mother how he knew that drug dealing was “frequently abundant” in the area traversed by Prince in his Jeep Cherokee on the fateful night, Carlton replied:

Well, I’ve lived in the area for almost all of my life. And I know that that area is somewhere that drugs and just about anything else that you want or don’t want can be found. I’ve also worked in that area with [the] Fourth District [police unit] and I’ve bought drugs in that area [as an undercover officer] on several occasions .... as a child and as a teenager I was always told that if it’s none of my business or it’s trouble, stay out of it. You go about your business and do what you have to do and let whoever’s doing whatever do it away from you.

“So this stuff was going on while you were a child and a teenager?” asked the attorney. “Child, teenager, adult,” responded Carlton. “It hasn’t changed.” He elaborated:

As I became an adult and I moved away from home, I wasn’t using that area to go back and forth across the city and I had no reason to be there, so I wasn’t there. ... [But] on occasion I would drive through with my parents on the way to church, and when you see people picking up prostitutes on a Sunday morning or doing drug deals on a Sunday morning, which is unusual in many cases where they try and keep it—people try and keep it out of sight and mind, you know that there’s a problem.

If Prince Jones was an intellectually gifted young man who benefited from an elite education, then Carlton Jones, too, manifested considerable promise, at least to judge from the pair of high schools he attended, Georgetown Day School and The School Without Walls, arguably the best private school and best public magnet school in DC. After enrolling in the US Army Reserves in 1985 and graduating from Walls in 1986, he spent the next two years at Valley Forge Military College, then transferred to Howard as a junior, converting his biology major to zoology.

Carlton spent a year-and-a-half at Howard, by his own estimate. The available record is bereft of detail about this period. His sojourn at the Mecca was as brief and unremarked as Prince’s was drawn out and celebrated. Yet both young men felt the pressures of a precarity that impinged upon the smooth sailing one might have anticipated for them by dint of their talents and educational background. “I had money problems,” Carlton acknowledged in a 2001 deposition, “and I did not finish. I have—maybe it’s five credits remaining.”

He drifted for a year after leaving, working as a salesman at a Jeep Eagle dealership, then at a K-Mart. In 1991, he signed on with the US Capitol Police, working there for the next two-and-a-half years until he left to join the Prince George’s County Police Department in 1994. The following year, after a decade in the Army Reserves culminating as a first lieutenant in command of an infantry company, he took an honorable discharge, presumably to devote full attention to his law enforcement career.

Yet any attempt to locate Carlton Jones squarely on the side of the ledger marked “honorable,” at least in the half-decade preceding the Prince Jones shooting, founders. Carlton’s biography, like that of the Howard man he would eventually kill, is haunted by shadows: chiaroscuro shadings that refuse easy assimilation into what might otherwise seem like a portrait of earnest virtue, an enterprising young man determined to serve his community and country.

Chief among these shadows was the January 1999 finding by an Administrative Hearing Board, convened by Prince George’s County and headed by police brass, that Carlton was guilty of making a false statement to an Internal Affairs investigator—doubling down on specious claims he had made on an earlier charging document filed against a black defendant—and guilty of an ethics violation for having done so. The defendant in that case, John Robert Johnson, who had an extensive criminal history including assault with intent to murder and robbery with a deadly weapon, subsequently became the plaintiff in a federal civil suit alleging battery and false imprisonment against Carlton and a second wrongful arrest suit against Prince George’s County.

On April 21st, 1997, Carlton, then still a low-ranking patrol cop, responded to a shots-fired call and arrived on the scene to find a PG County sheriff, Sergeant Collins, hunkered down in his car in the middle of the street, surrounded by spent shell casings, with another volley of shots ringing out. Johnson and his brother ran across the street; Collins, according to Carlton, kept repeating, “[T]hat’s them, that’s them, I know it’s them.” The two were apprehended nearby, searched—neither had a gun—and let go. More officers arrived, the crime scene was processed, and at some point, a weapon was recovered from the roof of a nearby building. Eventually, a decision was made by Carlton’s superiors to arrest Johnson. A four-car pursuit led by Carlton quickly chased him down, and Carlton was tasked with handcuffing Johnson and assembling the notes he’d been given by the other officers. With their assistance (“a group of officers in a football-sized huddle”), he charged Johnson with eight separate crimes.

All charges against Johnson were dropped within a week. It seems clear from the available evidence that the case against Johnson was always sketchy. But an officer’s life had been endangered by his proximity to this third-party firefight—Collins hadn’t actually been fired upon—and somebody needed to be punished. Carlton, as what his attorney later called “low man on the totem pole,” was being asked to do the dirty work, and fully aware of this, had executed the mission, conducting no further investigation and making false representations in the charging document. According to the Washington Post:

In the document, Jones alleged that when he went to the 7200 block of Landover Road to investigate a report of shots being fired, a county sheriff's deputy [i.e., Sergeant Collins] told him he had seen Johnson engaged in a gun battle with another man.

The charging document goes on to allege that a witness who called a police dispatcher identified Johnson as the person who threw a handgun on top of a building; police recovered the handgun.

According to law enforcement sources familiar with the internal investigation, the sheriff's deputy testified at the police trial board that he did not tell Jones he had seen Johnson engaged in a gun battle. In addition, investigators could not locate any audiotape in which a witness tells a police dispatcher that the gun had been tossed atop a building, and the existence of the witness could not be verified, the sources said.

What got Carlton Jones into trouble wasn’t so much that he’d made false statements in the charging document, but that he’d repeated exactly the same false statements to the Internal Affairs investigator, even though “he reasonably knew or should have known,” by that point in the game, “that no probable cause existed to charge the Complainant”—i.e., Johnson, who had filed suit against Prince George’s County. He lied to Internal Affairs and took one for the team, in other words, even as Collins threw him under the bus. “[S]o you’re the one with the– carrying the weight, so to speak?” Johnson’s attorney prodded him in a 2001 deposition, flushing out some resentment:

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And are you covering for anybody?

A: No, sir, I’m not. I’m just giving you what was given to me and that’s what I put down on the statement of charges....

Q: So you just assume if some other officer gives you information it’s truthful.

A: I used to.

This is the stuff of film noir, the ethical wilderness in which imperfect men engage in the dirty work society expects of them. But it also calls into question Jones’s integrity—a false arrest is a false arrest—and lays the groundwork, it would seem, not just for his later career in Information Operations with the Army Reserve, but also for his ongoing ascent, after a temporary demotion, into the world of undercover drug enforcement, where deceit is part of one’s professional toolkit.

Carlton Jones’s dishonesty in the John Robert Johnson case would come back to haunt him. It was alluded to in the very first story filed by the Washington Post after Prince Jones’s death (“The [police administrative hearing] board later found [Carlton] Jones guilty, the lawsuit said, although details were unclear”). And it exploded into view three months later with a second Post story, “Officer Had Filed a False Report,” offering revelations that Paul Butler, a law professor at George Washington University and former federal prosecutor, called “just devastating.” In July 2001, Prince George’s County prosecutors dropped two first-degree assault charges against Derrell Gilchrist, a drug dealer Carlton believed he was tailing on the night he killed Prince, because Carlton had initiated those cases and was now considered untrustworthy. “The fact [that Carlton Jones] lied in an official capacity has to undermine anything he is related to,” said Jack B. Johnson, the PG State’s Attorney.

When Coates later characterized Prince Jones’s killer as “a known liar,” in other words, he wasn’t wrong. Carlton Jones had demonstrated that ability at one particular moment early in his policing career, seeking to accommodate his superiors and then, when pressed, hardening defensively into the lie. “It seemed apparent that [Carlton Jones],” concluded the Administrative Hearing Board, acknowledging his awkward position, “although clearly responsible for his actions, was not given proper directions as to how to proceed with the establishment of probable cause.” By the same token, there is no evidence to suggest that Jones routinely lied on the job—unless one is speaking about his skill set as an undercover narcotics officer, where the ability to deceive those one is hoping to arrest is critically important.

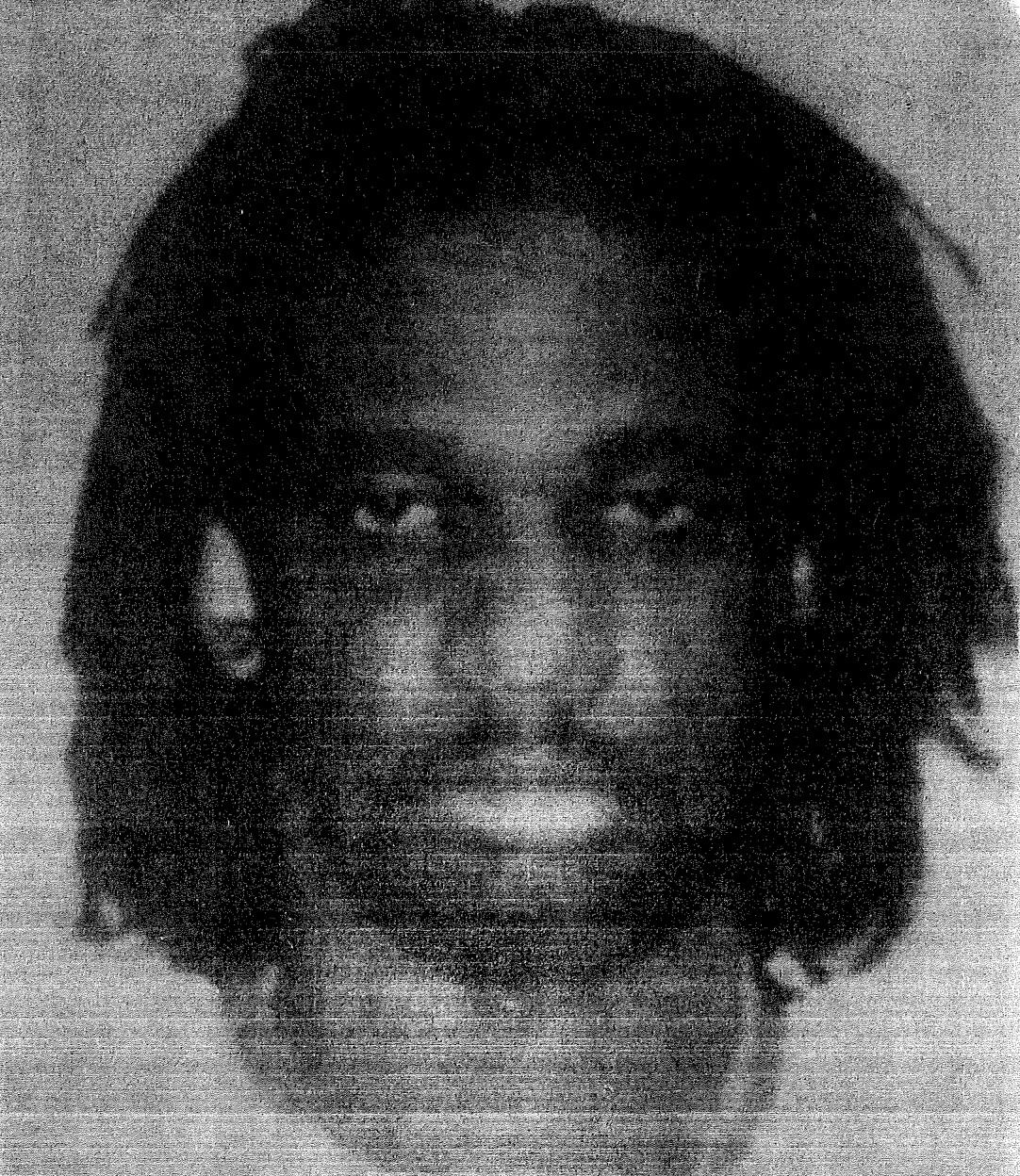

By the night of the deadly encounter with Prince Jones on September 1st, 2000, Carlton had been restored to his former rank and assignment as a corporal in the PG County Narcotics Enforcement Division and was, by his own estimate, working 10 to 16 hours a day. When he crossed paths with Prince, he was sporting dreadlocks and a beard, and wearing a white t-shirt and jeans. Asked in a deposition if he was “acting or playing the role of a Jamaican dealer,” he replied, “I have done that and I have played that role. I’ve played a buyer, I’ve played a seller.” The crack-using and -selling circles in which he moved were a particularly dangerous milieu, requiring split-second judgment in the face of unexpected and potentially fatal aggression. “[T]he whole [undercover] process is a kind of ‘role enterprise,’” argues sociologist Bruce A. Jacobs, featuring “deception-minded actors” who are “dramaturgically creating the perception that targeted subcultures should allow them entry, validation, and acceptance.”

Although Carlton’s professional career as a deception-minded actor appeared to be tracking in the right direction on the fateful night, his marital life was in disarray. The Post reported that, “Three days before the shooting, Jones’s wife filed for divorce, alleging that he had ‘committed adultery on numerous occasions’ ... [and] ‘engaged in a pattern of persistent conduct which is detrimental to [her] safety, health, and self-respect.’” She was seeking custody of their two sons. “Carlton was an all-right dude,” an upstairs neighbor at his apartment building told a reporter from People, but she added, “he appeared to be under stress.”

IV. The Writer

Seven years younger than Carlton Jones and the same age as Prince Jones, Ta-Nehisi Coates was born in 1975 and grew up in West Baltimore during the height of the crack epidemic—the same epidemic Carlton was still combatting more than a decade later, 40 miles south. The word “fear” occurs 56 times in Between the World and Me; the words “fears,” “fearful,” and “feared” together add another seven lashes to that accounting. Fear was the touchstone of Coates’s youth: the thing he could count on, for better or worse. And the police, a familiar presence in his distressed black urban neighborhood, were by no means the primary driver of that fear. He has been candid, not evasive, about that.

During an interview Coates gave to Terry Gross on “Fresh Air” in 2015, shortly after the publication of Coates’s book, Gross noted:

We’ve been talking about fear of the police and anger at the police. But part of your book is how you lived in fear when you were your son’s age—when you were a teenager—when you left the house ’cause there was a lot of violence in the neighborhood. And you say basically everyone in your neighborhood seemed to be reacting out of fear. You were afraid of other kids. You were afraid of your father’s beatings.

His parents, Coates told Charlie Rose, were “very, very educated people” who both worked.

Coates: Despite that, when I went out into the world, when I left, you know, for school every day, I confronted all the sort of things that all the other boys in my neighborhood and girls in my neighborhood confronted.

Rose: Which was the risk of violence?

Coates: All the time. All the time—constant, constant, constant. ... I look back and it’s insane.

To his mother’s chagrin, his father beat him badly—“kicked my butt”—when he was 14. “And she tried to stop him,” he told Gross, “and he said to her, you know, either I can do it or the police.” “My father was so very afraid,” he explains in Between the World and Me, speaking about an earlier whipping at age six:

I felt it in the sting of his black leather belt, which he applied with more anxiety than anger, my father who beat me as if someone might steal me away, because that is exactly what was happening all around us. Everyone had lost a child, somehow, to the streets, to jail, to drugs, to guns.

Streets, jail, drugs, guns. Aggressive policing is a part of this mix, but no more than a part. My concern, however, isn’t with Coates’s violent, fearful childhood, but with the way that this emotional inheritance and the safe harbor he found at Howard University shapes his portraits of Prince Jones and Carlton Jones. The deadly encounter between those two Howard men, which was fear-driven in a way that Coates refuses fully to acknowledge, is the crisis that animates Between the World and Me.

“I was admitted to Howard University but formed and shaped by the Mecca,” Coates writes. His invocation of that historically resonant term—not his invention, but one he is happy to claim—makes clear that he is crafting a religious myth preferable to the consolations of Christianity, the latter of which he rejects as “magic” and utterly inadequate to the enduring precarity of black life in America. “My understanding of the universe was physical,” he writes, repudiating the redemptive faith of Martin Luther King, Jr., “and its moral arc bent toward chaos then concluded in a box.” But the Mecca of Howard University? That’s a different story:

[S]till and all I knew that we were something, that we were a tribe—on the one hand, invented, and on the other, no less real. The reality was out there on the Yard, on the first warm day of spring when it seemed that every sector, borough, affiliation, county, and corner of the broad diaspora had sent a delegate to the great world party. ... [W]e have all we need out on the Yard. We are dazed here because we still remember the hot cities in which we were born, where the first days of spring were laced with fear. And now, here at The Mecca, we are without fear, we are the dark spectrum on parade.

We are without fear. The Mecca, for Coates, is the antithesis of West Baltimore’s mean streets. An unfallen black Eden, it heals the wounds those streets inflicted. Notes Black Arts Movement scholar Derik Smith in a 2016 essay for African American Review:

[T]he emotional high point of [Coates’s] narrative is reached when he describes the state of ecstatic safety experienced while held in the loving bosom of blackness that he finds at a Howard Homecoming tailgate party. Encircled by a reveling microcosm of “the entire diaspora,” he experiences a spiritual transcendence and a return to the womb, feeling himself disappear into the surrounding bodies of “hustlers, lawyers, Kappas, busters, doctors, barbers, Deltas, drunkards, geeks, and nerds” (147). In this climax of therapeutic nationalism the narrator himself dissolves, as do the apparently superficial differences that fracture black community in the neoliberal era.

Prince Jones is a part of Coates’s healing. Until, suddenly, impossibly, the murderous violence of the streets—a black cop dressed like a drug dealer, the lawman and neighborhood gangsta fused in one monstrous figure, 16 shots, a black body torn asunder, the whole swirling, fear-engendering miasma that young Coates struggled to survive back in West Baltimore—snakes out and claims him. At which point, within the religious schema Coates has set in motion, Prince becomes a blameless redeemer who has died for America’s sins.

The white dreamers and their blanketing regime of antiblack violence, stamped from the beginning on our national soul, have struck again. As they had done with Eric Garner, “choked to death on film under their laws,” and Trayvon Martin, a “slight teenager” whom they had transformed through “myth” into a “murderous juggernaut,” the dreamers “would rather see Prince Jones followed by a bad cop through three jurisdictions and shot down for acting like a human.” Coates is left bereft, spreading the gospel of Prince Jones and struggling to reassemble the fragments of a shattered Camelot.

How does Carlton Jones fit into this story? The short answer is: he doesn’t. He has no place in the Mecca. He has no place in Coates’s counter-mythology, one opposed to all the dreamers represent. To allow that Prince Jones’s killer, too, is a Howard Man—like Prince and Ta-Nehisi, and Ta-Nehisi’s father, who worked in the Moorland-Spingarn library, and Ta-Nehisi’s brothers, Damani and Menelik, who took degrees there—isn’t just psychologically intolerable for Coates, but sacrilegious. And the religious vision must be preserved, even if it leads us away from an honest accounting of what actually happened between the two men. This is why Coates infantilizes Prince even as he idealizes him, referring to him as a boy, twice, when first introducing him as the central figure in Between the World and Me:

The girl with the long dreads who changed me, whom I so wanted to love, she loved a boy about whom I think every day and about whom I expect to think every day for the rest of my life. I think sometimes that he was an invention, and in some ways he is, because when the young were killed, they are haloed by all that was possible, all that was plundered. But I know that I had love for this boy, Prince Jones, which is to say that I would smile whenever I saw him, for I felt the warmth when I was around him and was slightly sad when the time came to trade dap and for one of us to go.

But Prince Jones was not a boy. And Carlton Jones was not a bad cop. They, like Coates, were Howard men: gifted, aspiring, but flawed. Only human. Fated, it would seem, to explode into each other’s lives.

V. The Surveillance Operation

The legal framework through which the deadly encounter between Carlton Jones and Prince Jones was litigated can be quickly summarized. It doesn’t take us to the heart of that encounter, which is where we must go, but it offers several useful signposts.

In the immediate aftermath of Prince’s death, the decision about whether to indict Carlton fell to Fairfax Commonwealth Attorney Robert Horan. After an eight-week investigation, Horan decided not to prosecute, an outcome that produced widespread outrage, not least because Prince was unarmed and because both the official autopsy and an autopsy commissioned by the family found that five of the shots that hit him struck him in the back. “The physical evidence substantiates his [Carlton’s] version,” Horan insisted. “We didn’t have to rely on his credibility alone for anything because he was corroborated by witnesses. It happened the way he said it happened.” None of these claims—about physical evidence, corroborating witnesses, what actually happened vs. what Carlton claimed had happened—was, strictly speaking, true. But they were mostly true; true enough that no prosecution could have met the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard.

Horan also rejected the suggestion that Carlton and his supervisor, Andre Bailey, knew they were pursuing Prince Jones, intentionally targeting, following, and murdering him. Dismissing this conjecture required the prosecutor to acknowledge that something like gross negligence had occurred, leading the officers to pursue an innocent man. “It is clear from the evidence that Corporal Jones and Prince Jones did not know one another,” Horan said. “Prince Jones was not a man for whom they were looking. Prince Jones was not a suspect in the vehicular assault on Prince George’s police officers. As it turns out, the officers were incorrect in the assumptions they made about the black Cherokee [that Jones was driving].”

The FBI opened a criminal investigation, turning over its findings to the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department. In July 2001, 10 months after Prince’s death, Acting Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, William R. Yeomans, concluded that there was insufficient evidence to justify charges against Carlton Jones:

To bring federal criminal civil rights charges the evidence must support the conclusion that the police officer willfully deprived Mr. Jones of his constitutional right to be free from the use of unreasonable force. The federal statute requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt that a law enforcement officer acted with specific intent to use force that he knew at the time was unreasonable. Mistake, fear, or bad judgment is not sufficient to establish a willful violation.

Mistakes, bad judgment, and professional negligence are precisely the grounds, however, on which a civil suit may be founded. Although Carlton escaped criminal prosecution, he and the Prince George County police department were sued in civil court by attorneys representing Prince Jones’s surviving family: his fianceé Candice Jackson, his daughter Nina, his mother Mabel, and his father Prince Jones, Sr. These attorneys made a number of claims about Carlton’s intent and actions that could not be sustained by the available evidence and were later abandoned. But the attorneys were persistent, convinced that a fuller accounting was needed, and although early legal actions were unsuccessful, the proverbial day in court finally arrived.

In January 2006, after a two-week trial, the jury delivered a mixed verdict spearheaded by $3.7 million in damages, most of which was awarded to Prince’s daughter. “The jury found that Carlton Jones was negligent, used excessive force and could not have reasonably believed his actions were lawful. But it rejected a claim that the officer was liable for battery of Prince Jones, and it found that Prince Jones contributed to his death by his actions during the fateful encounter.” “[A] Prince George’s jury concluded the officer was liable for wrongfully killing an innocent man,” said family attorney Terrell N. Roberts III, celebrating the victory and finessing the split decision. “I think some justice has been served here.”

The jury’s insistence on attributing partial blame for what happened to the man who lost his life frustrates our yearning for a moral accounting that clearly distinguishes innocence from guilt, heroes from villains. Prince Jones was indeed innocent—the wrong man, a case of mistaken identity—until suddenly, in the heat of the moment, he was not. Perhaps this is why Coates makes no reference to the civil verdict in Between the World and Me or any of his other writings.

The deadly encounter between two bright, ambitious, and troubled young Howard men on September 1st, 2000, begins as the tale of two black Jeep Cherokees. The first of these was a 1996 model with Maryland plates, registered to Derrell Lamont Gilchrist, aka “Pig,” a short, stocky (5’6, 250 lbs.) drug dealer, 24, with an extensive criminal history. Gilchrist was well-known to DC and Prince George County police, and the leading suspect in the theft of a PG officer’s handgun from an unmarked police vehicle back in June.

In the weeks that followed, according to Horan, “Prince George’s police would twice encounter [Gilchrist] driving a black Jeep Cherokee with Maryland plates. Both times, [he] rammed police vehicles and escaped.” This wasn’t actually true. Gilchrist did evade capture twice, but he never rammed a police vehicle with his Jeep. In the first incident, he struck an officer with his Jeep; in the other incident, he used a different vehicle to swerve towards, but not hit, two officers. Carlton Jones was present during the latter incident and, thanks to several other interactions with Gilchrist, had a good sense of who he was.

The second black Jeep Cherokee was a 1998 model with Pennsylvania plates, registered to Dr. Mabel Jones of Philadelphia. When her son Prince (6’3, 211 lbs) turned 23, according to Coates, Dr. Jones bought it for him, presenting it to him with a “huge purple bow.” It was his daily driver, the car he used to shuttle between classes at Howard, work at the Bally’s health club, church, and visits with his fiancée and their baby daughter.

The two black Jeep Cherokees were not identical, although there was a basic resemblance, including dark tinted windows. On the fateful night, Carlton and his supervisor received a tip from an informant that Gilchrist’s Jeep, which was sometimes driven by his close associate, Chenier Hartwell (5’9, 135 lbs), had been spotted in an area of Northwest DC known for drug dealing. Although they had no police powers outside PG County, Carlton and Bailey drove to that area in separate unmarked cars and began slowly cruising the neighborhood. Then a black Jeep Cherokee swam into Jones’s field of vision—with Pennsylvania plates, not Maryland plates. But drug dealers were known to swap out their own plates in favor of stolen plates, so Jones took note. The car in question circled the block then returned.

An hour later, at the Cypress Creek Apartments in Chillum, a second location sometimes frequented by Hartwell that Carlton had decided to check out on his way back to the station, the black Jeep Cherokee suddenly showed up again, pulling into a parking space 100 yards away. This time, his suspicions aroused, Carlton called in the plates. They were registered to Dr. Mabel Jones of Philadelphia: a 1998 model Jeep, not the 1996 owned by Gilchrist. Neither the plates nor the Jeep had been reported stolen, but still: maybe Dr. Jones didn’t yet know about the stolen plates, or hadn’t yet reported them.

As Carlton watched, a black man got out of the car and went into a nearby building, but the streets were dark at 2am and the undercover officer couldn’t get a good look at him at that distance. Eventually, after nobody returned to the Jeep, Carlton decided to head home. He radioed Bailey, who agreed to call it a night. A few minutes later, at 2:30am, Bailey called him back: he’d seen the car again. It was heading out of town. Let’s go. And Carlton, exhausted from the long day and a lack of sleep piggybacked on his wife’s recent filing for divorce, went, albeit reluctantly. “I didn’t want to be there at the time,” he later acknowledged. “But I still go and do what I’m ordered to do.” He complied because his supervisor had instructed him to do so, and because chain of command meant something to the Howard man with a decade in the Army reserve and another decade in law enforcement.

All these details of a surveillance operation gone tragically wrong—with floating suspicions and unexpected coincidences coagulating into the early-morning pursuit of the wrong Jeep containing the wrong man—were deconstructed at trial with merciless precision by the Jones family’s attorneys, although the PG County attorneys had their own expert witness who insisted that professional standards of care had been maintained. Critical as these details were to the portion of the plaintiffs’ case focused on negligence, they are irrelevant to what comes next, except for the bottom line: one Howard man, an undercover cop with dreadlocks, dressed like a Jamaican drug dealer, was tailing his fellow Howard man across state lines—believing him to be a notably aggressive local drug dealer, possibly in possession of a stolen police weapon, and utterly in the dark about his real identity.

VI. The Pursuit

Prince Jones was having a fine night. At 10:30pm, after locking up at the Bally Total Fitness Club in Hyattsville, where he was a trainer/manager, Jones picked up his friend Vernon Robertson, 28, and the two men drove west into the District to the Macombo Lounge, a men’s club “featuring fully nude ladies, upclose and personal.” They spent a couple of hours there, drank relatively little, according to Robertson, and chatted at length. At 1:30am they decamped for the Cypress Creek Apartments in Chillum where Robertson’s girlfriend, Helana Johnson, was babysitting Prince’s infant daughter, Nina. They had no idea that their evening itinerary had intersected in both locations with Carlton Jones’s and Andre Bailey’s surveillance operation.

Prince’s fine night was supposed to have ended, baby in hand, in Falls Church, Virginia, at the home of his fiancée, Candace Jackson, but the trip to the Macombo Lounge had delayed that final leg. At 2am, Jackson called—unhappy, unsurprisingly, and wondering where Prince and the baby were. They talked for a while as Nina slept. When Prince got off the phone, Johnson made up the couch—Prince was getting ready to turn in, he and Nina were going to spend the night. Then Jackson called back.

The precise length and timing of these two conversations is unclear, but the result of the second conversation was a rapid change of plans:

About 20 minutes into the conversation, Jackson interrupted to say there was a knock at her door.

The visitor was a tall, skinny bartender with dreadlocks. Jackson had previously confessed to [Prince] Jones that she and the man had shared a one-night stand. But there he was again.

Jackson told Jones who the visitor was. Don’t worry, I’m going to tell him to leave, she said.

Jones was not pleased. I’m coming right over, he said.

“I told him that it was late, and he should get some sleep,” Johnson testified in court. But Prince would have none of it. Leaving Nina behind with Johnson and Robertson, he jumped in his Jeep around 2:30am and took off.

The 15-mile drive from Chillum, Maryland, to Falls Church, Virginia, takes 20 minutes at that lonely hour. Down through the District past the US Capitol, over the 14th Street Bridge past the Jefferson Memorial, looping around the Pentagon and Arlington National Cemetery on I-395, then a straight shot west on US 50. Prince was pushing hard, for obvious reasons. Carlton, trained to avoid detection in this sort of surveillance pursuit, lagged several hundred yards behind on the open highway, keeping the Jeep’s taillights in view.

At some point, according to Carlton, the driver of the Jeep appeared to become aware that he was being tailed. Carlton speaks in several of his depositions about how the driver began “cleaning himself”—a law-enforcement term for deliberately erratic driving (speeding up and slowing down, changing lanes) designed to foil and/or flush out an undercover pursuer. Carlton has been consistent on this point. Is he telling the truth? Plaintiffs’ attorney Terrell Roberts will warn the jury in his opening statement to be skeptical, since this detail could be invented, a bit of embroidery designed to buttress Carlton’s claim that he believed he was tailing a savvy criminal, not an innocent man. Prince, after all, isn’t around to contradict him. “We don’t know what he [Prince] knew,” Roberts reminded them. But then, in a rare moment of agreement between plaintiffs and defendants, he conceded—indeed, asserted—the point. “But we think that we have proven here that he became aware at some point that he was being followed.”

Less than a mile from his fiancée’s apartment, aware by now that he was being tailed, Prince exited US 50 onto the westbound service road, continued for 30 seconds, and then made two quick sharp lefts that U-turned him onto the eastbound service road. Then, after another 30 seconds, he made a sharp right onto Beechwood Lane. As he neared the bottom of Beechwood, just before the intersection with Spring Terrace, he slowed, gliding left into the curving quarter-circle driveway that fronts the house on that corner lot, rolling to a stop at the far end with his car facing Spring Terrace. He cut off his lights and waited.

Carlton had no idea where he was, although he and the Jeep had ended up somewhere in the Seven Corners portion of Falls Church. The neighborhood was unfamiliar to him. Keeping an eye on the Jeep’s taillights in his rearview mirror as it doubled back along the eastbound service road, he watched it turn right, up a side street. He quickly made the same U-turn the Jeep just made and headed east in pursuit, juggling his phone to call Bailey, who was a couple of minutes behind. When he reached that side street, the taillights had vanished.

He swung his Montero right and cruised up Beechwood Lane past a handful of large suburban houses, a leafy late summer enclave. Stopping at the intersection with Spring Terrace, he scanned right. No red taillights. Then, a hundred feet down on the left side, he spotted the dark silhouette of what appeared to be the Jeep, lights off, facing the street at the end of a semicircular driveway. “I’m kind of thinking, maybe I got lucky,” he will tell the Internal Affairs investigator later, “and you know this is the same jeep, maybe he’s home. ... [S]o, I made the left and I started down the street.”

VII. The Shooting

What happens next will change the course of two men’s lives. One man will kill; the other man will die. The dead man will be unable to bear witness; the killer will be required to do so on multiple occasions over the next six years: in an interview with the Fairfax County Homicide Squad at 7:55am on September 1st, 2000, only five hours after the incident; in a written statement and a separate sit-down interview, 12 days later, for the Prince George’s County Police Department, the latter being a “duress statement” conducted by Internal Affairs; in a summary interview with the FBI, dated January 25th, 2001; in a pair of depositions for separate civil trials, conducted in August 2001 and September 2005; and, lastly, in courtroom testimony given during the second civil trial, dated January 10th, 2006.

The story that Carlton Jones tells twice on September 12th, 2000, and that hardens into a set piece he retells with great fidelity and conviction over the next five-and-a-half years, varies subtly but crucially from the story he tells on September 1st, shortly after the shooting. He has no idea at that early moment that the man he shot and killed is named Prince Jones—not until he sees that name in paperwork on the desk of the Fairfax County officer who interviews him that morning in his bleary-eyed, sleep-deprived state. He certainly has no idea that Prince Jones is a fellow Howard man until the news explodes across the Washington Post in the days that follow. The attorney provided to him by the police union advises him not to watch the news or read the newspaper, but we may assume that a fellow officer or two lets him know who he has killed. It’s a big fucking deal. So he gets his story straight.

The story Carlton Jones evolves is mostly true. It is much more true than some of the wilder conjectures proffered by the grieving family and their outraged lawyers. But it is not entirely true. It is phase-shifted in the direction of providing him with a stronger self-defense rationale for having emptied all 16 shots in his Beretta through the back window of the Jeep that just happened to contain his much-beloved Howard brother, Prince Carmen Jones. It will take the 2006 civil trial with all of its discovery, including depositions from two eyewitnesses and testimony from a vehicular accident reconstruction expert, to give us—and the jury—a purchase on the actual truth: the story behind Carlton’s story, based on a preponderance of the available evidence.

Here is how the encounter begins:

After making a left onto Spring Terrace, Carlton cruises slowly down the block, keeping the stationary black Jeep Cherokee with dark tinted windows in view off to the left through his open driver’s-side window. (Carlton’s open window is a key detail; a plaintiffs’ attorney will grill him on it.) He is not looking to apprehend or arrest the Jeep’s occupant, he will insist—he has no police powers in Virginia—but merely to note the plate and residential address for later follow-up.

Prince is sitting in his idling Jeep, watching the grey sport-utility vehicle approach slowly from the right. Just before it reaches the driveway, Prince flicks on his lights, hits the gas, and shoots out into the street with a rapid rightward swerve that angles him on to Spring Terrace, heading back in the direction his pursuer has come from, towards Beechwood. For a split second as the two vehicles nearly collide before slipping past each other, Prince is able to see the other driver—black, with dreadlocks—in his headlights through the Montero’s open window. His fiancée’s lover? The man he drove out here to ward off, pursuing him? We can’t know for sure what thoughts rush through Prince’s head, but Prince George County police officials will later float this explanation, and it makes sense.

Startled by the sudden explosion of lights and motion on his left, Carlton has the presence of mind to veer right, out of the path of the careening Jeep. “I’ve been burnt,” he thinks. The subject of surveillance—Gilchrist, he assumes—has figured it out and fled. Carlton resolves to call off the chase and return to the station. Rather than continuing down the block into a darkened neighborhood he does not know, he yanks the wheel hard left into the beginning of a three-point turn, stopping the Montero in the middle of the street, perpendicular to the roadway.

Carlton hasn’t had time to finish his three-point turn, when he sees the Jeep reversing quickly but smoothly in his direction—red taillights, white backup lights swelling in his face until the brake lights flash bright red and the Jeep’s rear bumper comes to a T-bone stop only an inch or two from his door, pinning him inside the Montero. He can’t open his door even if he wants to. Trapped, sighting down the Jeep’s left flank, he sees the front door swing open in the darkness and a man jump out. He’s black, tall, slim, and he’s not Gilchrist, Carlton realizes.

As the man trots silently towards the open window of the Montero, Carlton reaches his right hand down into his waistband, pulls out his Beretta, and points it. “Police, get back in the vehicle!” he shouts. “Police, get back in the vehicle!” Panicking, he’s had no time to reach under his shirt for his badge before the tall man stops, turns around and, without a word, runs back along the Jeep’s flank, then jumps in, slams the door, and takes off.

In the space of ten seconds, the paradigm within which each man has been working is shattered. Neither man is the person the other man believed him to be. Which is why Prince, who may well have intended to scare his wife’s dreadlocked lover, ends up saying nothing during this encounter—or so the evidence suggests—and why Carlton forgets to show his badge. After the shooting, Carlton will tell the 911 dispatcher that he believes he has shot Gilchrist’s associate Chenier Hartwell, although Hartwell is six inches shorter and 75 pounds lighter than the man he has just confronted. But he knows, even now, that something is very wrong. This guy is not Gilchrist, that’s for sure. But who is he?

A compassionate God would stop time at this precise instant, cleave it in two and set things right. Nothing irreversible has occurred yet. No gun has been fired; no bullet has struck flesh or bone. Prince can still drive away unharmed to Candace’s doorstep a few blocks away. But he doesn’t do that, and now the tragedy ensues—a tragedy partly of Prince’s own making. Coates understands how unfair the situation is, and how inevitable:

I tried to imagine myself in Prince’s shoes. The officer who was tracking him was not in a normal police cruiser. The officer was not in uniform. The officer, in fact, testified that he pulled out his gun, said police but did not– never showed Prince his badge. The officer was dressed in an undercover disguise like he was supposed to be a drug dealer. And you know, this is how insidious it gets. I have to imagine myself followed from the suburbs of Maryland, through DC, out into Virginia—realizing at some point that I’m being followed, not having any idea that this is a cop and then having somebody pull a gun out on me and knowing that I’m near my fiancee’s house. So it always seemed to me perfectly logical, you know, that Prince perceived that he was under threat.

Does Prince think Carlton is an undercover cop, or a drug dealer pretending to be a cop? The latter seems more likely, but we will never know. We know only that two young, gifted, and ambitious Howard men with a shared hunger for military service, placed in a situation that makes them incapable of seeing each other as the brothers they are, get each other terribly wrong.

The story Carlton tells about this tragedy—the set-piece he creates shortly after Prince’s death, reiterates with minor variations for the next six years, and hews to at the civil trial—has three acts. It is like a well-constructed play, except the entire production lasts no more than a minute. The opening sequence, culminating with Carlton’s doubled exhortation, “Police, get back in the vehicle!” and Prince’s retreat, is merely the prologue.

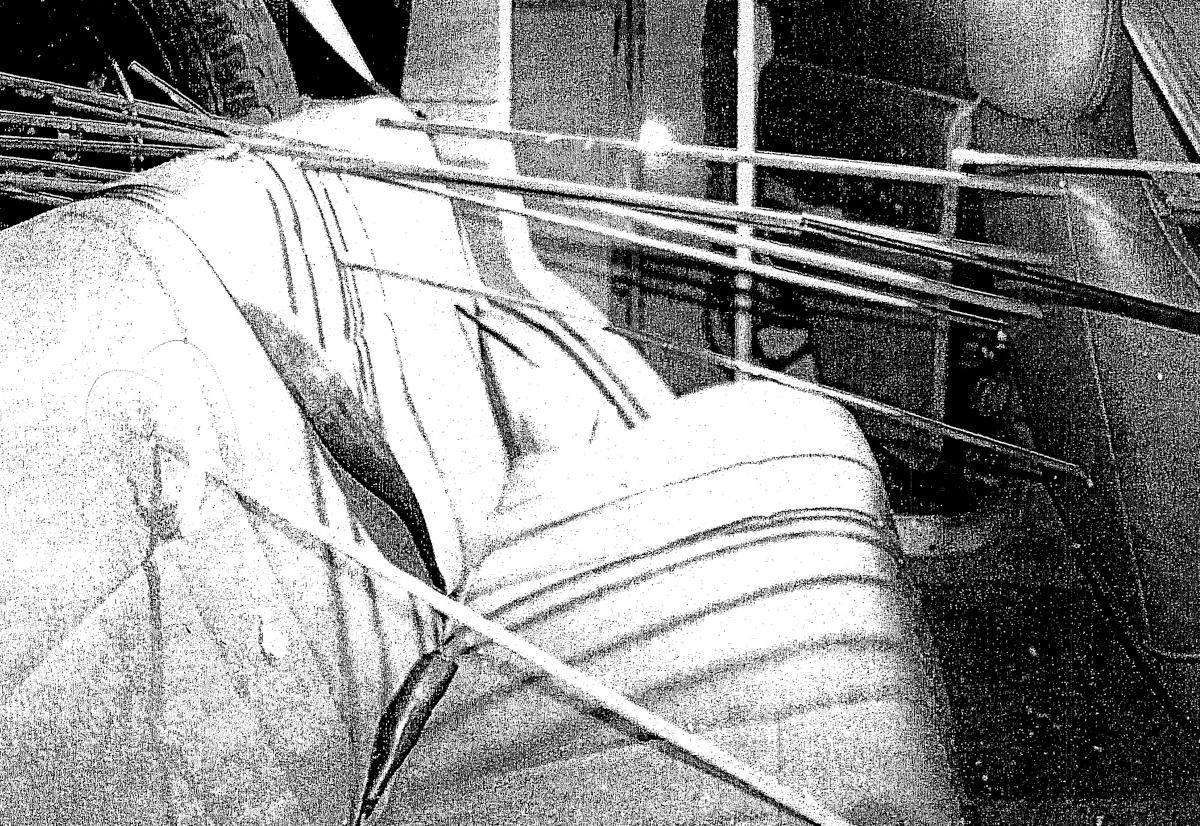

§ Act One: Carlton is sitting in his idling Montero on the wet, dark street, still perpendicular to the roadway, his three-point turn uncompleted. “I kind of relaxed a little bit,” he acknowledges in one deposition, thinking he’s scared the Jeep driver away. But the Jeep, it turns out, has stopped only two or three car-lengths ahead. Focused on re-holstering his Beretta, Carlton looks up in astonishment to see the Jeep reversing rapidly in his direction and striking the side of the Montero with its back bumper, “ramming my car with considerable force.” It’s a solid hit, square on the door.

§ Act Two: Startled, temporarily disoriented, Carlton struggles to put his car in gear. It has an automatic transmission with a center-console shift, and he is unable to get it into Drive. The Jeep pulls forward after ramming him, a little further than last time, and then he hears the engine racing and sees the tires smoking, the white backup lights shining as the Jeep squeals into view and rams his door a second time, much harder than before. This time he is thrown to the side, halfway across the console, as the Montero rocks violently. He tries frantically to unsnap his seatbelt and put the Montero in gear, but he’s unable to accomplish either task. He will mention the Jeep’s revving engine and smoking tires in every iteration of this story, along with his inability to get his own car in gear.

§ Act Three: The Jeep pulls forward a third time, a little further than the first and second times, then reverses once again. This time, Carlton will tell the Internal Affairs investigator, the engine sounds as though the driver has really stomped the gas:

I mean I could hear the wheels spinning, it’s like he punched it and the tires weren’t grabbing or something and it it’s just and as I was trying to ah, I kind of gave up trying to get the car in gear. I was just trying to get out the seat belt and get over to the other side of the car and I just, I don’t remember consciously, like drawing and firing.

Carlton’s next recollection is of looking down at his pistol, seeing the slide locked to the rear, hearing the crack of safety glass dropping from the blown-out rear window of the Jeep, so close he can almost reach out and touch the space where it was. There are shards of broken glass in his dreadlocks, in his lap, on the front seat. “[I]t seemed like he intended to kill me, hurt me, fuck me up, whatever you want,” Carlton will reply when asked why he’d shot at the vehicle. “I had no idea, I was scared. I couldn’t make the car work to get out of the way.”

He felt he had no choice but to shoot in the face of impending murderous assault, although he can’t actually remember firing any of the shots. Emptying his Beretta in the seconds before impact, miraculously, seems to have stopped the Jeep in its tracks, warding off the third strike. After a couple of seconds, the Jeep’s driver—hit by multiple shots and now mortally wounded, although he will hold on for another six hours—squeals off into the night, crashing into a hedge two blocks away, just across the street from his fiancée’s house.

VIII. Complicating Testimony

The story Carlton Jones tells is his story, not Prince Jones’s story, although Prince plays a critically important role in it. And it is mostly true. It gives every indication of honoring the emotional core of his experience. His ability to remain faithful to those emotions and most of the facts while adjusting narrative elements on an as-needed basis so as to place himself in a more advantageous position vis-à-vis the relevant criminal and civil codes is an acquired skill. But it is not the gold standard demanded by American jurisprudence, which asks for the whole truth and nothing but the truth. It diverges in important ways from what actually happened.

There were two eyewitnesses, as it happens, to much (but not all) of what happened between the Jones men on Spring Terrace that night: Letitia “Lettie” Ballve and her husband Juan. Their video depositions have disappeared in the intervening years but they were played at the civil trial and later referenced by both plaintiffs and the defense in a way that gives us some purchase on their contents. The Ballves’ son Nathan, in addition, was an earwitness and then eyewitness; his statement, which broadly confirms the testimony of his parents, was not referenced at the trial. And there was an accident reconstruction expert, a civil engineer named Al Cipriani, who testified for the plaintiffs. When Carlton Jones’s story is subjected to the reality principle represented, albeit unevenly, by the Ballve family and Cipriani, it begins to fray at the edges.

On the night of the shooting, the Ballves resided at 6441 Spring Terrace, on the southeast corner of the Beechwood Lane intersection. Their ground-floor bedroom, set somewhat back from the street, had a window that looked directly out onto the scene of engagement. Lettie was awake at 2:50am, nursing a sick dog. When she saw lights coming through her bedroom window, she got out of bed and looked out.

Lettie’s testimony, as filtered through attorneys for both plaintiffs and defense, contains some anomalies, some “facts” that don’t fit, and in one case, are directly rebutted by the physical evidence. (She claimed to have seen the Montero shoved ten feet sideways by the Jeep, not the eight inches measured by Cipriani.) But both attorneys, with minor variations, highlighted her key claim: two successive rearward hits by the Jeep. “[S]he saw,” said the Jones family attorney Terrell Roberts, “the Jeep back up and hit the Montero. She says it pulled up again about eight feet and then backed up again and hit the Montero.” “[S]he does clearly recollect the ramming on two occasions,” agreed the PG County attorney, Jay Creech. “She does clearly recollect that this vehicle pulls forward 10 to 15 feet and then accelerates rapidly backward at an even greater speed than the first time.”

So far, so good for Carlton Jones. Neither Lettie nor her husband, as it happens, saw the pre-collision encounter—the Jeep’s initial blocking maneuver, the tall black driver jumping out and approaching the Montero, Carlton’s repeated command, “Police! Get back in the vehicle!” All this could have happened before Lettie first peered through the bedroom window. A preponderance-of-the-evidence standard, in any case, argues strongly for Carlton’s truthfulness here, for two reasons.

First, if the scene hadn’t taken place, Carlton would have continued to assume what he’d been assuming all night, which is that Derrell Gilchrist was almost certainly driving the Jeep and was, therefore, the person he’d shot. It was only this brief, startling encounter with a much taller, slimmer man which forced him to recognize that he’d been mistaken about the Jeep’s occupant. This led him to tell the 911 operator, shortly after the shooting, that he believed he’d shot a man named Chenier Hartwell.

Second, if Carlton had invented this encounter, he would have had no reason to confess, on the record, that he’d neglected to show his police badge when he ID’d himself as a cop, since his failure to follow this established protocol made him look unprofessional. The fact that he did share this embarrassing detail when he could easily have lied about it suggests that he was telling the truth, at least about this element of the story.

His account runs into trouble, however, when confronted with the testimony of Juan Ballve. Lettie, standing at their bedroom window and alarmed by what she’s seeing, calls out to her husband. Come to the window, she says. There are cars in our yard. I’m going to call the police. Waking, Juan rouses himself and heads for the window. Just before he gets there, he hears a single impact: the second impact, from his wife’s perspective. Looking out, he sees two vehicles in a T-position. Neither car is moving. Within a few seconds, gunshots erupt.

Juan Ballve’s testimony blows a hole through the third act of Carlton Jones’s carefully curated drama. For more than five years, Carlton has been insisting that the Jeep, after a second harder hit, rolled forward some distance and then reversed a third time, its tires spinning as it hurtled in his direction with palpably murderous intent. Unable to free himself from his seatbelt or shove the transmission into Drive and escape, he was left with no choice but to shoot. Hard, harder, hardest: the three-part logic undergirding his story is compelling. He killed in self-defense, because “hardest” might have killed him. He killed to prevent that third hit.

As an officer of the law in the state of Maryland, Carlton was intimately familiar with self-defense statutes. Anybody in his position would have brushed up on Virginia’s self-defense statutes at the first available opportunity after the shooting. Virginia law only allows a person to use deadly force against another individual if he reasonably believes that there is a clear and present danger of death or great bodily injury from an “overt act” committed by that individual.

But Carlton had survived the first two hits. And there was no overt act, as per the self-defense statute; no threatened third collision manifesting a clear and present danger. Neither of the Ballves, watching and listening, saw or heard anything like that. Their son Nathan, up late in a street-facing computer room when the shooting occurred, told investigators “that he heard screeching tires, an impact, more screeching tires, another impact, then gunshots. He then heard tires squealing again and”—he’d clearly parted the curtains by this point—“saw a car driving down Beechwood Lane.”

Carlton didn’t fire in the final seconds before a third and presumably deadly impact, to prevent that impact. Nor, as the Prince Jones family attorneys suggested in an earlier civil suit, did he shoot Prince in the back as he was driving away. Carlton fired shortly after the second, harder impact, while he and Prince sat in their conjoined and battered cars. Momentarily stunned by that impact, Carlton panicked. This is what a preponderance of all the available evidence suggests. And then, when he realized later just how much was at stake, he came up with a story that shaded what had actually happened to his legal advantage while retaining a solid enough purchase on the underlying material and emotional realities that it would be difficult to disprove.

Here it is useful to touch on the testimony of Al Cipriani, a witness for the plaintiffs who was brought on, as a “fully accredited Traffic Accident Reconstructionist,” to talk about the physical evidence. Cipriani, a mechanical engineer by training, is the co-author of papers with titles like “Low Speed Collinear Impact Severity: A Comparison Between Full Scale Testing and Analytical Prediction Tools with Restitution Analysis.” What he brought to the civil trial was a cool, moment-by-moment appraisal of the physical forces that actually spiraled through the Jeep and Montero as they engaged in their deadly dance—the antidote, in some sense, to the charges and countercharges, the furiously heightened emotions, the narrative embroidery and narrative enlargement, that had, from the beginning, characterized the panoply of responses to Prince Jones’s death. Cipriani’s findings, although not—as he was quick to acknowledge—completely determinative, would place immoveable bookends on certain kinds of stories and speculations.

Cipriani was given access to the battered Montero, allowing him to measure crush damage to the front and rear doors, along with police photos of both vehicles and a comprehensive array of photos and measurements of the accident scene on Spring Terrace. His conclusions? At the point of impact, moving in reverse, the Jeep was traveling at approximately eleven-and-a-half miles an hour, within an estimated range of between nine and 14 miles an hour. That impact resulted in a lateral (sideways) speed change for the Montero of between four and eight miles an hour: six miles an hour, nominally.

“Approximately six miles an hour?” asked the plaintiffs’ attorney. “That’s the speed with which it rocks to the side?” Cipriani: “That is correct.” This impact, as noted on the police report, caused the Montero to skid sideways eight inches on damp pavement. The maximum inward damage to the Montero’s door, according to Cipriani’s measurements, was less than one inch. “I’m just trying to get an idea,” the plaintiffs’ attorney persisted, “of what that means when a car is rocked sideways from—going from zero to four to eight miles an hour.” Cipriani: “In vehicle accident reconstruction, we would normally classify that as low speed impact.”

Turning next to the fraught question of how many times the Jeep had approached and/or collided with the Montero, Cipriani offered as evidence both the photos of skid marks contained in the police report and his own close visual inspection and measurement of the scrapes and striations found on the Montero’s door. His top-line assessment was unambiguous: the police documented a total of one shorter rearward acceleration mark, estimated by Cipriani at just under 15 feet, and two longer acceleration marks heading west, away from the scene of impact.

The striations on the Montero’s door were inconclusive, showing evidence of either two impacts or, more likely—although not “within a degree of engineering certainty”—only one impact. “Yes, that could have been two impacts,” Cipriani said, “but it’s also just as likely that ... it could have been something where the metal bent on the way in and you have one set of scrapes on the way in, and as the vehicle left and the metal popped back out, you got another set of scrapes.”

For anybody looking to take Carlton Jones’s three-act tale at face value, Cipriani’s sober assessment, distinguishing what was possible from what did not and could not have happened, was the starkest sort of reality check. Prince’s Jeep had indeed charged the officer in reverse, at least once and possibly twice—a relatively light impact followed by a harder second impact. The rearward acceleration mark on Spring Terrace confirmed Carlton’s claim about the tires smoking and squealing on the second approach. But that impact, although hard enough to skid the Montero eight inches sideways, was not the sort of metal-mangling collision designed to cause serious bodily injury that one might have assumed from Carlton’s statements. Unsurprisingly, Carlton had survived that second hit essentially uninjured. As for the threatened third and devastating blow made with murderous intent, “wheels spinning” as the Jeep’s driver “punched it”: there was no evidence for that, on any front. Carlton almost certainly invented it.

Or, more precisely, he had transformed the second impact—the sounds and sights that accompanied it, his fear-soaked and traumatic experience as an officer under vehicular attack—into an imagined third impact, an impending mortal blow that needed to be stopped by any means necessary. He hadn’t lied so much as expanded and elaborated, anchoring his invention in the truth of his own feelings.

IX. The Rule of Three

All of this narrative flim-flam becomes obvious the moment one goes back and reexamines the very first account Carlton Jones gave of the deadly encounter to Det. David W. Allen of the Fairfax County Police Department, only five hours after it took place.

Carlton had no idea who he has shot at this point, although he will soon see Prince’s name in paperwork on Allen’s desk. Prince was in critical condition but hadn’t yet died, so it wasn’t technically a homicide investigation. Carlton knew himself to be the opposite of a gun-happy hothead. Before that night, he had shot at a suspect just once and missed; that suspect was later arrested and Carlton’s use of force was found to be justified. The only other time he had discharged his weapon was to ward off a wounded dog.

Yet here, defending himself from an inexplicable and apparently unjustified vehicular attack, he had emptied his Beretta and left his unknown antagonist on the verge of death. Even as he narrated his experience for Allen, he was probably struggling to make sense of the panic, the loss of professional cool, that lay at the bottom of his actions. Ten years in the US Army Reserves, almost a decade in law enforcement. He’d been schooled, drilled, in the proportional use of force. And now this. What the hell had just happened?

He began with the pinning-maneuver prologue, then sketched for Allen the outlines of the three-act drama that he would finalize within the next 12 days: