Art and Culture

Sculpture and Story

Narrative art has been deeply unfashionable for about a century. But aren’t art and stories inextricable?

I.

It’s baloney, the romantic reputation of artists’ garrets. Hot as a blast furnace in summer, my studio leaked like a sinking ship in winter. It was the attic of an ancient building in dockland Dublin upon which gentrification’s cloud had yet to descend. It’s been a decade but never shall I forget that mustard-coloured ceiling. It looked like a H.R. Giger creation, covered with a web of foam insulation that swelled and bulged obscenely in high winds.

The décor didn’t bother me though. I was sculpting my Nebuchadnezzar (pictured above). You may ask why I did not simply call him Old Man with Beard? Aside from pretension, obviously. Sure, galleries like a daunting title to distract from the price tag but most contemporary critics say that any sculpture that needs a backstory is flawed, that a form is interesting in itself or a failure. A rose by any other name and so on.

There’s some truth to that, but for me, names are crucial. I knew who I was meant to sculpt before I hefted a dozen bags of clay up the rickety stairs. Nebuchadnezzar, in the Biblical account, was a Babylonian king whose persecution of the Jews incurred the wrath of God. The king was struck mad, reduced to eating grass like a beast. Readers will be more familiar with William Blakes’s haunting and oft-reproduced version but consider that continuity: two artists separated by two centuries, both depicting the same crazy old man.

Both are examples of Narrative Art, a mode which art-history buffs know has been deeply unfashionable for about a century. The norm in Blake’s time, today it’s seen as anachronistic, lowbrow and kitsch.

As a child in the 1980s I was blissfully ignorant of this dogma. I liked stories. Biblical stories like Nebuchadnezzar’s and Irish legends like that of the boy-warrior Cuchulain stopping Queen Maeve’s invasion of Ulster singlehandedly. I liked Greek and Norse heroes too. Theseus, Odin One-Eye, all that mad gang. I even invented stories. My brother and I hoarded an army of toys which we periodically divided to fight epic week-long campaigns. I was drawing by then too, although I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t. Naturally, I drew story characters. Playing with a pencil was no different from playing toy soldiers.

Growing up, we’re told to put aside childish things. In secondary school, I learned that what I’d been blissfully engaging in was a dreadful thing. Tellingly, if people today think of Narrative Art at all, they think of history paintings. Cesare Maccari’s 1888 canvas Cicero Denounces Catiline, for example, is technically impressive but if you don’t know the story, a famous episode from Roman history, it’s just a bunch of dudes in togas.

Art that makes these kinds of demands increasingly came under fire in the Victorian era. Nobody likes homework. The painter Whistler expressed how irrelevant he considered subject matter to be by giving his portraits titles like Symphony in White. The subversive idea of Art for Art’s Sake steadily took hold, especially in fin de siècle Paris. The Impressionists, I was taught, heroically faced down an Academy that had become moribund, stale, and oppressive. This account, I would discover, is decidedly one-sided but it is true that the Impressionists’ successors rejected the finicky realism of the Academy and its subject matter—especially stories from history and myth. A Cezanne still life from 1905 and a Henry Moore sculpture from the interwar period have little in common except a lack of story.

By the middle of the 20th century, storyless art was no longer the exception. It was the rule. My teachers called this progress. A discarding of useless tradition for something far more sophisticated. I believed them. I didn’t like it necessarily, but I shrugged and said, “I guess that’s how it is.” For me, art and stories were inextricable. I just had to find another way to make a living with a pencil.

II.

The logical end of art as play is, I think, the cartoon. And if a cartoonist aspires to collect a steady wage, a sensible career is animation. It’s also one of the only types of art education today which needs to reliably produce competent draftsmen. Admittedly, the intellectual air among students is less lofty than it is at other art colleges. Debates among animation students concerned practical matters like why Micky wore gloves and Daffy didn’t. Certainly, no one was agonising about Narrative Art. Small wonder. Students can make all the experiential films they like but if it’s over a minute and doesn’t have a character or plot, ain’t nobody watching.

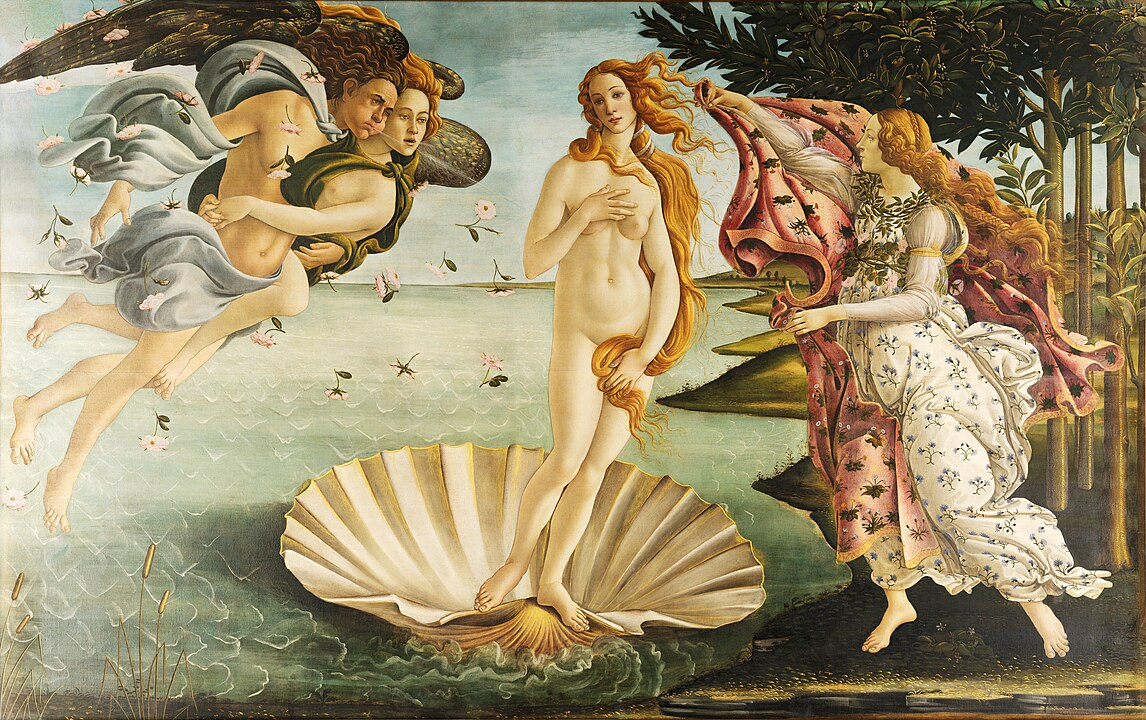

This is natural. The storytelling instinct is very old. It’s rude to mention a lady’s age but the Venus of Willendorf is thought to be 30,000 years old. Any visitor to Vienna’s Natural History museum who sees this prehistoric carving knows exactly what the artist meant by it. It’s a story about a goddess of love, fertility, and bounty. It’s retold by the Venus de Milo and Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, and the 1989 Broadgate Venus made by Botero, the Columbian sculptor who died this month.

Such stories connect us. To our ancestors. To each other. They have utility. A story gets us to work every Monday. A good story takes us to war. A great story, to the moon. What are these things, that have such power to motivate us collectively? They are not often, strictly speaking, true—Hamlet has no more reality than the Divine Right of Kings. Narnia isn’t a place any more than a Human Right is an object. Animals often deceive each other, playing possum or mimicking predators, but our fictions are more potent and protean. They work even when we know they are stories. A ten-pound note is piece of paper that we agree to pretend is valuable. That pretence is key. A puppy pretends to be angry. Another pretends to be scared. Then roles reverse. Playacting, they learn skills that may later save their lives, and have fun doing so.

At first, making cartoons was as much fun as watching them. Short films can be solo runs but animation for TV and feature films is a team sport. In 1999, some likeminded students and I set up a studio in my hometown Kilkenny. It was a gamble. Cartoon Saloon is now a big Oscar-nominated employer. Back then, it was a handful of brilliant artists who preferred to tell our own stories rather than work for studios like Disney. The siren song of Fine Art still called but I was too busy to listen. The early 2000s were heady years of experimentation, doing service work, commercials and illustration, establishing a name.

The dice roll paid off as we got our projects off the ground. I created and directed the studio’s first TV show, Skunk Fu. It appeared on the BBC, the Cartoon Network and Canal+. The show had a budget of several millions, a year-and-a-half schedule, and crews in three timezones. One team in Kilkenny, one in Vancouver, and one in the Philippines. As director, any day might find you rewriting a script for one show, reviewing storyboards, checking animation rushes for another show, all while supervising a recording or edit of yet another.

At first, it’s exciting. Over time, it’s a drag. When there are problems with an episode, you must suppress the instinct to fix them and instead do triage. Is this too bad to pass or will it do? Stop too long to correct one weak show and you delay five episodes coming down the pipe. Animation is not a pure art where you can seek perfection as long as you goddamn please. On TV budgets, it’s more like politics, the art of the possible. Without daily compromises, you fail. But it takes a spiritual toll.

III.

Just before my show was greenlit, I made a pilgrimage. Part of maturing involves questioning stories you’ve been told, and I began to suspect that Fine Art had not in fact progressed in the early 20th century. It had, I increasingly believed, merely turned into a blind alley and blithely kept going. Only I wasn’t sure why.

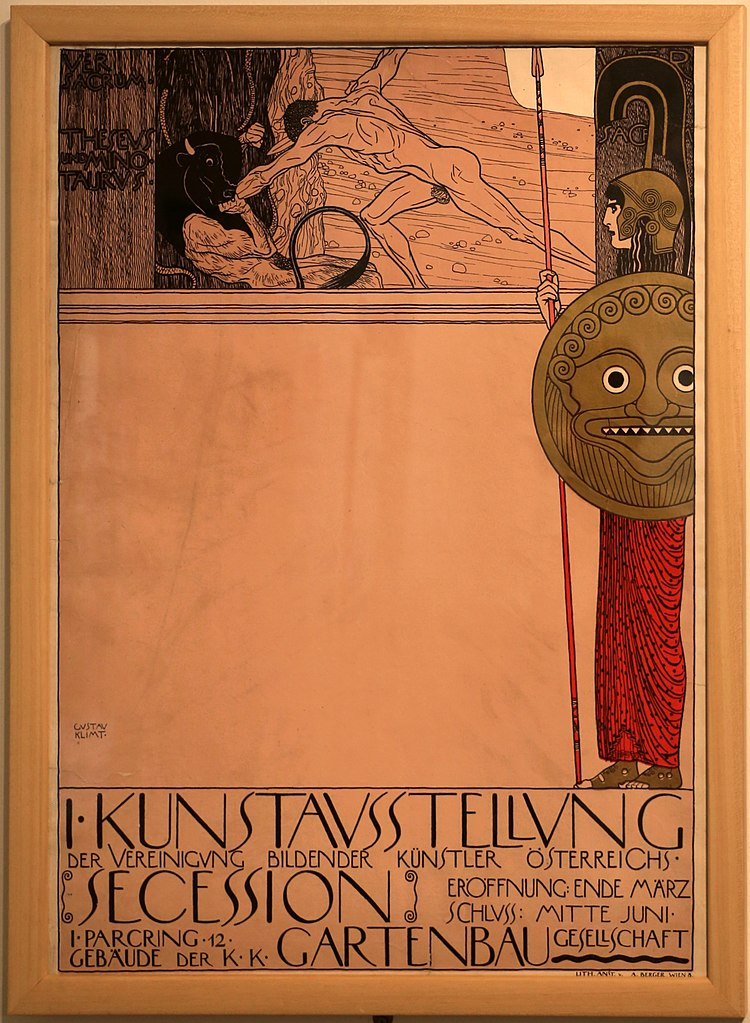

I sought an answer in Vienna. Even though Paris was the cultural Mecca when what we call Modernism was pioneered, it faced stiff competition from the Viennese Secession. The leading light of this rebellion was Gustav Klimt. An exceptional draughtsman who responded imaginatively to modernity, he had a graphic sensibility, and used pattern, texture, and—dare I say it—abstraction in his painting, and yet he still told stories.

Look at his poster for the Secession’s debut exhibition below. With characteristically sensuous lines, Klimt depicts the Greek hero Theseus killing the minotaur. The message isn’t subtle. The beast the vigorous young hero is dispatching was the Künstlerhaus, the grey-haired establishment unwilling to change in an epoch characterised by change. I read with approval the motto beneath the gilded foliage that caps the Secession Building, “To every age its art, to every art its freedom.”

But here the story takes a turn—the good ones always do.

While exploring the art of the previous age in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, I found another Theseus. This Theseus was bludgeoning a centaur. Busy guy. The huge marble sculpture, the work of the Italian virtuoso Antonio Canova, adorns the museum’s central staircase. It was carved a century before Klimt’s revolt. Canova was a Neoclassical champion of order. Klimt was an impish sex-mad disrupter. Yet both artists drew inspiration from the same Greek myth. One can be a rebel, it seems, without forgetting one’s roots.

Different artists, different ages; a hundred years before I flew to Vienna seeking enlightenment, another sculptor around the same age took a different path. In 1904, 27-year-old Constantin Brâncuși walked from Romania to Paris. After a short spell in Rodin’s studio, Brâncuși announced that, “Nothing can grow in the shadow of a great tree” and he left. By 1907, he had strayed far indeed from Rodin’s influence. His cuboid statue The Kiss renders the most human of acts into something harshly geometric.

In 1913, he took part in the now-famous Armory Show. It was New York Society’s rude introduction to the stars of the Parisian avant-garde—Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp et al—and Theodore Roosevelt was unimpressed. “The lunatic fringe,” the ex-president wrote, “was fully in evidence, especially in the rooms devoted to the Cubists and the Futurists…” Most histories frame this as a canonical moment—America’s first chance to see the latest European art. But why it was Europe via Paris and not Vienna usually goes unasked.

Sure, Paris had a happening scene but Vienna was no cultural slouch. In 1913, you could waltz off the Ringstrasse into a café, order your morning strudel, and sipping a cappuccino one table over could be… anyone. Sigmund Freud maybe, or Theodor Herzl, Stefan Zweig, Walter Gropius, Puccini, Schoenberg, Trotsky, Hitler, Tito, or Stalin. That said, you probably wouldn’t find the Archduke Franz Ferdinand dining streetside for fear of anarchists like the one who in 1898 assassinated his aunt Elizabeth.

I couldn’t find why things fell apart in Vienna but by the time my TV show wrapped I knew my future wasn’t in Kilkenny. Animation is a fast-moving business. Leaving meant leaving. Financially speaking, it was rash. Director is the best-paid job in animation. But it didn’t matter. The story I’d told myself, that telling my stories on screen would satisfy, just wasn’t so—not really. I had to find another.

IV.

The Florence Academy of Art is an American-run atelier devoted to teaching traditional skills. You learn as Klimt or Rodin or Brâncuși learned. You copy old master drawings, plaster busts, and finally the model. Copy means copy. The aim is to reproduce what you see accurately. You’re there to train your eye, not to express yourself. Sculpture students draw and sculpt the model lots but the first exercise is copying the features of Michelangelo’s David. Swallowed in sections, it seems digestible. One soon learns the subtlety with which the maestro varies his surface, hard edges turning to rounded planes, conveying now bone, now muscle.

It’s a deep immersion. Charcoal life drawings that you spend weeks and even months on, and écorché classes where you study anatomy, sculpting the body from the skeleton up (a flayed figure made by the young Brâncuși in 1901 can still be seen in Bucharest), and weekend visits to museums, sketchpad in arm. I had a season pass for the Uffizi and beside my apartment in the Centro Storico was the Bargello, the world’s best collection of Renaissance sculpture. A good omen.

The model who sat for my first portrait was called David. Another good omen. Already a decent draughtsman, I rapidly absorbed the lessons taught. A good thing too—American college fees are as high as you’ve heard. As well as learning the secrets of dead masters, your fellow students are a living example. And if they’re good, the teachers are great.

The twin towers of the sculpture facility were both American but I thought of them as Mozart and Beethoven. Robert Bodem, an irrepressibly cheerful chap, founded the sculpture course. He was like Canova in his controlled balance and harmony. Cody Swanson, a young prodigy, was a more melancholy soul. His work was more textured and tortured.

Perhaps a more important difference is that Bodem, like most modern artists, rarely aspires to tell a story. His goal rather is to capture a pose, like a great dancer can, so clearly and elegantly that you see the body’s beauty anew. The first Bodem I saw, the piece that drew me to Florence in fact, was called Petrushka. A seated figure stretches, his arms reaching up. Awakening perhaps, his body unfolds like a flower before dawn. Petrushka is a stock character in Russian puppet theatre and the pose resembles that of a marionette. It’s a clever name, but you could call it Male Nude No.1 and it would be the same piece. It is what it is.

While I was studying, Swanson toiled away day and night behind his studio’s locked door, emerging occasionally with the dusty face of a soul in perdition to gruffly give instruction. My classmates wondered if he was making a monster in there. In a way he was. On what must have been a good day, he showed us. He unveiled a figure, a man with a stooped and twisted body making a strange gesture. This was Judas, the disciple who betrayed his friend the Son of God. Casting away the worthless silver, the traitor goes to hang himself. His contorted pose, I saw, mirrored the pose of Rodin’s Adam. Swanson revered Rodin but this was more than homage. A visual parallel was drawn between expulsion from Eden and damnation to Hell.

Two sculptures: one plotless, the other loaded down with it. It is idle to debate which of these is better—both are exceptional—but it is the former, art that makes no attempt to tell a story, that is now dominant. Though unusual, one can find precedents of this austere mode before the 20th century. The purpose of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave is to decorate a pope’s tomb, nothing more. Rodin’s homage to Michelangelo, The Age of Bronze from 1877, likewise has no story. Not really. These are beautiful bodies, beautifully posed, beautifully sculpted. Nothing more.

Bodem once confessed that his favourite sculptor was Brâncuși. This surprised me at the time. It now makes sense. Admirers once called Brâncuși, “The Patriarch of Modern Sculpture” (patriarchy had a better reputation then). It was Bird in Space that cemented his status. Earlier versions of the bird were inspired by a Romanian fairytale. By the 1930s, Brâncuși had abandoned story and almost everything else. Bird in Space is pure form.

This sculpture caused a famous legal dispute. Brâncuși was by then selling well in America but when he tried importing his latest work, the customs official didn’t recognise it as sculpture (“If that’s art, hereafter I’m a bricklayer.”) and slapped on the usual 40 percent tax for imported industrial goods. Edward Steichen, an admirer and owner of Brâncuși’s work, took the matter to court. Even if he lost, the publicity would make it worthwhile. Thanks partly to pro bono representation from lawyers of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Brâncuși won. Yes, the judge decided, although Bird in Space may be unrecognisable as such, that’s irrelevant: pure abstraction can be art.

If that controversy now seems hilariously quaint, that only shows the power of dogma. Since the debates have been “settled” for nearly a century, we’ve forgotten how eccentric this view is historically. Consider a counter example.

Like Brâncuși’s Bird, you can admire Michelangelo’s David as a beautiful form but if you ignore its story you’re missing out. This is the shepherd boy who became the king of Israel. But Florence isn’t Jerusalem. Why is David so far from home, in a town in Tuscany? A town with a strong wool and banking sector but no obvious connection to David. Sure, Florentines were zealously religious at times but why David? Why not Abraham, Jacob, or some other Biblical patriarch? Come to that, why are there so many Davids in Florence? Donatello’s bronze is 60 years older than Michelangelo’s marble while Verrocchio’s lesser-known version is 40 years older. What’s the story?

Florentines saw themselves as the underdog. Armed only with a sling, David defeated the Philistine giant because David was God’s beloved. Florence too was special. It overtook Sienna, its old commercial and military rival, in the early quattrocento. When Michelangelo was carving his colossus, new Goliaths loomed on the horizon, Rome to the south, Milan and France to the north. No matter. Florence would best them all.

Not knowing that story, can you admire the statue? Of course. Many do. But they are missing why Michelangelo made it and what it meant to his countrymen. More importantly, they are missing David’s essential drama. Equally, to enjoy the Sistine Chapel, we are not obliged to believe in Christ’s Resurrection or the Last Judgement—there isn’t a test before you enter the Vatican—but for more than a superficial appreciation of these treasures, we must know their story. This isn’t a quirk of Renaissance Christianity either. An admirer can parse the Hellenic Laocoön or Rodin’s Burghers of Callais just as profitably. Those masterpieces too are stories.

In Florence, I learned modelling well but little about what comes next. Quite right too; bronze is costly and little that students sculpt is worth casting. Still, after learning the fundamentals, I began to feel that Shadow of a Great Tree feeling that told Brâncuși it was time to go. These modern ateliers do vital work but they are by necessity hermetic environments. Gaining a deeper appreciation of the Old Masters can be empowering or it can be overwhelming. Students get addicted to pursuing perfection. Some never leave. Cheap Italian table wine is another temptation. But some things can only be learned outside academic walls. I was impatient to make new mistakes.

V.

Dublin has two foundries either side of the Liffey. Walking from my latest studio to see my latest casting over the last decade, I came to know the city’s monuments well. I studied them so that if and when I got a chance to make one, I’d be ready.

In the heart of Dublin is the GPO, a stately post office building. Inside, stands a bronze statue by Oliver Shepherd. It depicts my old playmate Cuchulain. The dying hero has strapped himself to a pillar to keep his enemies back as long as possible. The Goddess of Death, impatient for killing to continue, lands in the form of a crow on his shoulder to show the invaders the truth. It’s a fine Edwardian sculpture but what is it doing here? Cuchulain was from Ulster—has Dublin no native heroes of her own?

Like David, The Dying Cuchulain is a story Dublin told itself. It’s a story brought to the world’s attention by Lady Augusta Gregory. While young Brâncuși was learning sculpture in Bucharest, she was learning Irish and collecting folktales from tenants on her Galway estate. Her 1902 translation of the ancient epic poem, the Táin Bó Cúailnge, was an international sensation. Theodore Roosevelt, who would hate the Cubists in 1913, adored Cuchulain. As did Mark Twain. As did Irish nationalists seeking native heroes. In plays and poetry, Lady Gregory and her friend W.B. Yeats weaved a story that captured a whole generation.

One of those who took Cuchulain’s story seriously was a sculptor’s son and a teacher named Padraig Pearse. Under a stained-glass window of the hero, his students learned to speak the Irish their parents had abandoned. Around the time Brâncuși and co. were causing a stir in New York, Pearse had moved from resisting British culture to plotting revolution. On Easter 1916, with the British army mired in the mud of the Western Front, Pearse and his fellow conspirators struck. After holding out for week in the burning GPO, he surrendered. He was executed on May 3rd. His brother Willie, a fellow rebel and a sculptor like their father, was shot the next day.

Along with Lady Gregory, W.B. Yeats had laid the groundwork for the cataclysm. He was torn between guilt and amazement at its “terrible beauty.” In a poem called The Statues, he asks “When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his side/What stalked through the post office?” This is no more a poet’s fancy than Blake’s Jerusalem. Yeats quite literally means the heroic spirit was present. His mysticism is often mocked but, considering the aftermath, it’s undeniable that a new spirit was abroad in those years. Though Pearse’s revolt was short-lived, its effects were profound, leading within a few years to the independence of most of the island. This, when the British Empire was still hegemonic.

Shepherd’s statue was erected in 1935 in a very different Ireland. By then, Ireland’s leader was an old rebel who’d fought alongside Pearse but escaped execution. The Easter martyrs were heroes who toppled a British Goliath.

Ireland in 2023 has largely abandoned that compelling if simplistic story. This is the last year of what was bombastically branded as our Decade of Centenaries, a sequence of anniversaries between the outbreak of WWI to the end of Irish Civil War. Start to finish, the commemorations were an embarrassment, a battery of damp squibs. Modern Ireland has no notion which story to tell about that transformational epoch and certainly not about the Easter Rising. The State can’t bring itself to celebrate an undemocratic minority’s illegal and violent insurrection. They can’t condemn it either. So they mumble platitudes and hope no one is offended.

Oliver Shepherd drew inspiration from Celtic myth but as the 20th century progressed few Irish sculptors followed his example. Artists are as susceptible to trends as any other group, perhaps more so. Oisín Kelly is an honourable exception. His lively and dramatic monuments are beloved by Dubliners—sculptures like The Children of Lir in the Garden of Remembrance—but his was a lonely path. More representative and more widely patronised was Kelly’s student, Micheal Warren. Warren’s 10-meter-tall abstraction, perversely titled Woodquay, stands in front of the buildings that Dublin Corporation built on top of one of Europe’s most important archaeological sites in the 1980s. Warren is skilful but I think of this colossus as a vandal’s middle finger pointed at Dublin.

Certainly, the ubiquity of this cold international style made it seem that some law of nature was operating. The banal truth is that abstraction spread as fast as mid-century cities sprawled because its impersonality leant itself to easy duplication – its facelessness appealed to the faceless institutions who are art’s modern patrons, state bodies and the corporations that increasingly resemble them. Strong emotion of any kind fills bureaucrats with horror. If a taxpayer or customer could dislike the story a statue might tell, it is only prudent to commission work that says nothing. And as the managerial state reached its peak, it’s no mystery that artists bent to cater to it. If post-war sculptors have stories, they’ve either lost the nerve or the skills to tell them. No one says they are following the money; they say something like, “Narrative is a suffocating limitation.” Most of them even believe it.

How is that possible? We’ve seen how long storytelling art has been around. Such a sea change is more than fashion. What shock would it take to break a tradition older than agriculture? How about a war that kills 11 million soldiers, and as many civilians? The year after the Armory Show, Archduke Ferdinand visited Sarajevo and did not return. Yeats, who saw the Great War as civilizational suicide, captures the slaughter’s impact using an ancient image, “A shape with lion body and the head of a man.” His sphinx “slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.”

Yeats feared that the vacuum left would loose an atavistic anarchy upon the world. Sure enough, the 1920s were fertile with bad ideas: prohibition and eugenics in America, fascism in Italy and Germany, communist dictatorship in Russia. Everything old was suspect, everything new, modern and “scientific” was worth a try. That’s why Paris and its self-conscious novelty-seeking art scene defined the zeitgeist. Among the Great War’s casualties was the Austrian Empire. Klimt wasn’t around to see the full collapse. He died in Vienna in 1918, the same year his most gifted student Egon Schiele perished from Spanish ’flu.

We live among the ruins, like Dark Age peasants. They too believed everything transpired providentially. The reality—that things fell apart and were never rebuilt—is too horrifying to contemplate. But Dark Ages don’t last forever. “Weeping may endure for a night,” sang King David, “but joy cometh in the morning.”

VI.

When I finally won a public commission—for Ennistymon, a little town in County Clare—I was determined to retell a folktale I’d first heard as a boy. The Púca is a shapeshifting fairy who often appears as a talking horse. A trickster, he waylays drunken travellers at crossroads. Depending on his humour and their manners, he may grant them a fortune or drop them down a bog hole. Sure enough, my long preparation helped me make The Púca but nothing could have prepared me for the controversy that erupted when Ennistymon’s parish priest denounced my lovely horse from the altar.

When I saw the “Pagan idol” headlines, it occurred to me that if Pearse summoned Cuchulain to the GPO, perhaps I had inadvertently summoned the Púca. The tale turned out to have more twists than a goat’s horn, too convoluted to relate here. Suffice it to say that the fairytale ended happily with my wild statue ensconced in the heart of that wildest of Irish landscapes, the Burren. He’s fast becoming a west coast must-see, his big toe already polished to a shine by tourists making wishes.

The striking Puca sculpture created by Aidan Harte has found its home at the Michael Cusack Centre. Its one of Irish folklore's greatest Characters carrying mortals to fairyland. @HarteAidan @ClareTourism #thepuca #gaa #fairyland #folklore pic.twitter.com/CrqVsCC78V

— Visit the Burren (@visitBurren) November 4, 2022

Though terrific fun, the bizarre episode may be a pyrrhic victory if I never win another Irish commission. Last month I was finally shortlisted for one. It’s up in Roscommon, the realm of Cuchulain’s mortal enemy, Queen Maeve. My design shows the man-eating matriarch standing proudly, and quite nude, with her captured prize, the Bull of Cooley. Provocative? Certainly. It’s also true to her brazenly sensual character in the legend.

Does that matter? Probably not. If Púca was too grotesque, Maeve surely is too sexy. But let’s see. The best stories always surprise…

This essay expands upon remarks delivered by the author at the Clifden Arts Festival this year.