The Pseudoscience of Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory is not a hard science. It’s not even a soft science.

In Is Everyone Really Equal?, Özlem Sensoy and Robin DiAngelo (of White Fragility fame) argue that Critical Race Theory (CRT) educators are like professors of hard science. In one passage, the authors ask their readers to imagine that they are in a class on planets, taught by an astronomy professor. The professor asserts that Pluto is not a planet (largely due to its shape). A student insists that it is. The professor corrects him, but the student remains obdurate. The same dynamic of stubborn ignorance is at play, the authors assert, when ordinary people disagree with Critical Race theorists. Contradicting a core tenet of CRT is as “nonsensical” as arguing with someone with a doctorate in astronomy about basic facts about the solar system.

DiAngelo and Sensoy describe their hypothetical student defiantly concluding that “Pluto was still a planet, even if it was shaped like a banana.” This, they argue, is equivalent to claiming, “I treat people the same regardless of whether they are ‘red, yellow, green, purple, polka-dotted, or zebra-striped.’” One key tenet of CRT is that we’re all unavoidably racist, and treat people differently based on their skin color. For DiAngelo and Sensoy, the idea that someone might not act this way is as absurd as the idea that a banana-shaped lump of rock might qualify as a planet.

In reality, however, Critical Race Theory is not a hard science. It’s not even a soft science. In fact, the field is plagued by pseudoscience. So, what makes an argument pseudoscientific? As the philosopher Karl Popper puts it, “statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible, or conceivable observations.” If an idea can be falsified, then it is (or could be) scientific. If it cannot, it’s merely pseudoscience.

Critical Race Theory is full of unfalsifiable arguments. In White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism—perhaps the most famous CRT book in the world—DiAngelo argues that every single white person is racist. According to her, “racism is unavoidable and … it is impossible to completely escape having developed problematic and racial assumptions and behaviors.” She considers various reasons why white people might deny the fact that they are racist—such as that they “married a person of color,” “have children of color,” or “marched in the sixties”—and summarily rejects them. For DiAngelo, it doesn’t matter what you do or who you choose to associate with. It doesn’t even matter how you treat people of color. If you’re white, you’re racist. Full stop.

In fact, according to DiAngelo, if you’re white and you reject this premise, that makes you even more racist. “White people who think they are not racist … cause the most daily damage to people of color,” she writes. In this worldview, disagreeing with DiAngelo’s accusation is simply taken as proof of the validity of said accusation. This is a logical fallacy known as a Kafka trap. It is pseudoscience in the strictest sense.

DiAngelo’s entire thesis is presented as a Kafka trap. She coined the term “white fragility” to describe the way white people respond when accused of racism. The characteristics of “white fragility” include “argumentation” (i.e., vocal disagreement), “silence,” “leaving the stress-inducing situation” (that is, the room in which the person is being informed of their racism), “guilt,” “tears,” and “anger.”

If you’re white, any failure to acknowledge your racism is simply additional proof of your guilt. If you are unable to admit your own racism, you will respond with “fragility” by denying it, getting upset, remaining silent, or walking away. Once you have been accused, there is no way to rebut the charge except by rejecting the entire framework of DiAngelo’s argument.

This kind of circular argument is not unique to White Fragility. At the 2014 National Race and Pedagogy Conference at Puget Sound, Heather Bruce, Robin DiAngelo, Gyda Swaney (Salish), and Amie Thurber developed several core tenets of anti-racism, one of which is: “The question is not Did racism take place? but rather How did racism manifest in that situation?” This tenet takes what should be a hypothesis (that racism manifested in situation x) and turns it into an axiom. It is unfalsifiable not because racism manifests in every situation but because the authors refuse to even countenance the idea that it might not.

Indeed, the entire system of Critical Race Theory rests on the unfalsifiable assertion that society is pervaded by “systemic racism.” As the Critical Race Studies in Education Association puts it, “the social construct of racism affects every part of our lives and mitigates truth, citizenship, humanity, and property.” This is a form of the Marxist idea of “false consciousness”: the notion that workers who do not see themselves as part of an oppressed class have internalized their oppression and replaced their true class consciousness with a false one. In Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic define it as a “Phenomenon in which oppressed people internalize and identify with attitudes and ideology of the controlling class.”

According to CRT, if you are a member of a racial minority and do not see yourself as oppressed by systemic racism, you are laboring under a “false consciousness” caused by “internalized oppression.” If you are white and disagree with the tenets of CRT, you have been influenced by “oppressor ideology.” Either way, any disagreement with the idea that racism is endemic is simply further proof of the sheer pervasiveness of racism. Once more, the argument is unfalsifiable.

Another strikingly pseudoscientific feature of CRT is the Interest Convergence Hypothesis, developed by legal scholar Derrick Bell, one of the founders of CRT. As Delgado and Stefancic explain, this hypothesis posits that “because racism advances the interests of both white elites (materially) and working-class whites (psychically), large segments of society have little incentive to eradicate it.” Civil rights gains for people of color can therefore only come about when they also benefit white people and “coincide with the dictates of white self-interest.”

In support of this, Bell cites the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education—the landmark court case that led to the desegregation of US schools—which, he argues, was driven by the white desire to win the Cold War. The US was competing for the loyalties of uncommitted nations, many of which were non-white. If stories of segregated schools reached these nations, they might lose interest in allying with the supposed land of freedom and opportunity for everyone. Thus, according to Bell, white and black interests briefly converged.

This argument is unfalsifiable because white people are not a monolith. There were 134 million white Americans in 1950, according to the US Census Bureau. Those people had a range of different interests and goals. Some whites certainly viewed racial desegregation as merely a way to curry favor abroad. Others did not. For every advance in Civil Rights, a dedicated CRT scholar can always comb the historical record and find plenty of whites who stood to benefit from it. At the same time, whenever Civil Rights were rolled back, the same scholar could find plenty of whites who benefited from those rollbacks. The Interest Convergence Hypothesis is unfalsifiable for the same reason that Freudian psychotherapy is unfalsifiable: the framework can retroactively justify anything that happens.

So, why do so many CRT scholars make unfalsifiable arguments? One reason is that CRT is heavily influenced by postmodernism, which rejects the very ideas of truth and objective reality. As Education Week’s associate editor Stephen Sawchuk puts it in an article praising CRT, “Critical race theory emerged out of postmodernist thought.” Delgado and Stefancic concur: they write that CRT “draws from certain European philosophers and theorists, such as Antonio Gramsci, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida.” Foucault and Derrida are often considered the intellectual standard bearers of postmodernism.

As Christopher Butler notes in Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction, postmodernism rejects the idea of a universal reality that we can all access or observe. Butler describes the idea that “universal truth is impossible” as a “typical postmodernist conclusion.”

For postmodernists, truth is impossible to know, and scientific thinking is simply one “discourse” (i.e., way of talking about the world) among many. As Butler writes, “even the arguments of scientists and historians are to be seen as no more than quasi narratives which compete with all the others for acceptance. They have no unique or reliable fit to the world, no certain correspondence with reality. They are just another form of fiction.” When modern CRT scholars argue that there are many “alternative ways of knowing” and that science is no more automatically legitimate than, say, indigenous myths, they are echoing a postmodernist argument.

It is probably for this reason that many CRT scholars explicitly reject the scientific method. In Is Everyone Really Equal?, DiAngelo and Sensoy note that “Critical Theory developed in part as a response to this presumed infallibility of [the] scientific method.” For CRT scholars, the scientific method—the notion that hypotheses should be verified by testing their predictions against reality before they are accepted—is merely one of many ways of knowing. After all, if there is no objective truth, and scientists’ and historians’ ideas are no more valid than fiction, why would you subject your ideas to any such test?

We need more efficient ways to tackle racism, which poses one of the thorniest problems in social psychology. Racism is an outgrowth of tribalism, and tribalism is a deep-seated human impulse. In almost every society throughout human history, people have oppressed and excluded each other on the basis of immutable characteristics. In India, Hindus have spent millennia arguing that human beings are born into hereditary castes, opposing inter-caste marriage, and denying social privileges to non-caste Hindus like tribals and Dalits (who, until the 1970s, were known as “untouchables”). In Kenya, citizens war with each other based on which tribe they were born into. Western Europe has a history of antisemitism that stretches back centuries and continues to this day. According to the Anti-Defamation League, which measures and records antisemitism, as much as 24 percent of the population of Western Europe may harbor antisemitic attitudes. And the United States, of course, has a brutal history of racial oppression through slavery and Jim Crow laws.

However, racism varies from individual to individual, just like other psychological traits. Some people—and therefore some societies and institutions—are more racist than others. Identifying the extent to which a specific person, system, or society is racist requires careful, precise scholarship. Simply saying that all white people are racist (as DiAngelo does) or that the United States is “systemically racist” won’t do.

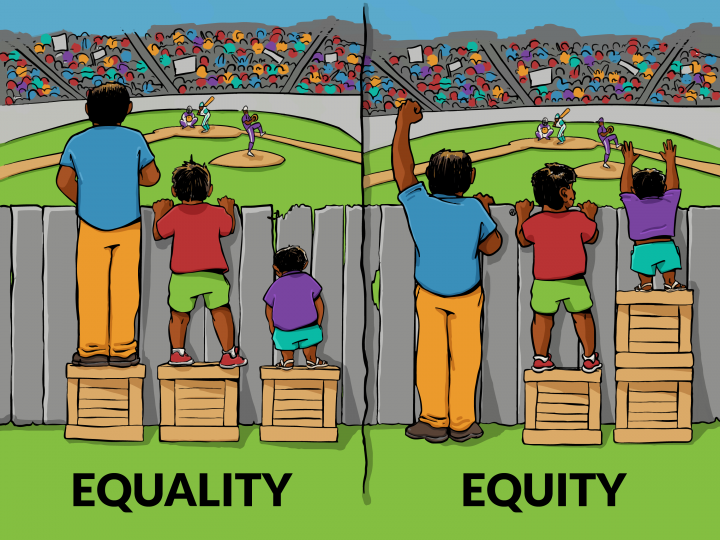

There is a popular equity cartoon (see below) in which boxes are stacked to allow three different people to each see over a fence and spectate a baseball game.

The image is designed to highlight the problem of failing to compensate for the unequal distribution of social advantages. In order to give each baseball fan the correct number of boxes to stand on, you first have to know how tall they are (how much privilege they possess) and therefore how much they need to be boosted to see the game. Without this knowledge, you risk failing to address the problem (as in image 1) and may even make it worse.

The problem is that obtaining this knowledge is not a trivial endeavor.

Suppose you start from the hypothesis that traffic stops are carried out in a way that discriminates against people of color. In order to test this idea, you first have to identify a pattern (e.g., black motorists are more likely to be pulled over than white motorists). You then have to design a study that controls for other variables, such as the neighborhoods in which the traffic stops take place. If all the white motorists were stopped while driving through swanky, low-crime communities, while all the black motorists were driving through an impoverished ghetto, for example, that would be a confounding factor. If you find evidence that people perceived as black and those seen as white receive different treatment ceteris paribus, then you have to identify the scope of the discrepancy. If you’re trying to make an argument about traffic stops across the entire United States, you would have to carefully examine data from many different locations in order to see whether racism is more prevalent in some areas than others. This kind of social science work contributes immensely to our understanding of modern-day race relations. However, every step of this process requires utilizing the scientific method and accepting the notion that “universal truth” (in this case, the extent to which black motorists are discriminated against in traffic stops) both exists and is observable. Unfortunately, many CRT scholars reject one or both of these premises.

We probably can design effective interventions that will help reduce racism—but surely only if we use the right epistemological tools. We must formulate and test hypotheses, trial our interventions and be ready to modify or abandon them based on whether they work on the ground. In other words, we must address this problem using the scientific method. If interventions to reduce racism aren’t well thought-out and carefully tested, they can actually make the problem worse.

Many of the current antiracist measures have not been subjected to any empirical testing. Diversity training programs, for example, are a common feature of both corporations and nonprofits, but according to sociologist Musa al-Gharbi they don’t actually work. As Al-Gharbi puts it, “for … behavioral metrics, the metrics that actually matter, not only is the training ineffective, it is often counterproductive.”

Al-Gharbi suggests that such trainings teach people to say the right things in post-training surveys, but don’t improve how they actually interact with minorities. In fact, he argues, these trainings can be counterproductive: “By articulating various stereotypes associated with particular groups, emphasizing the salience of those stereotypes, and then calling for their suppression, they often end up reinforcing them in participants’ minds.”

Practitioners of rigorous social science believe in a discernible universal reality and employ precise epistemological tools to identify features of that reality. This method doesn’t always yield accurate conclusions, but it is our best hope of moving closer to the shared understanding of the truth that will enable us to address pervasive human problems.

CRT scholars reject the empirical method, which means that they lack the capacity to develop an accurate understanding of our world. Relying on CRT to diagnose and address racism is like relying on crystal healing to cure cancer—no matter how smart or well-intentioned the practitioners are, they are unlikely to succeed.