A daily diet of Ukrainian news has familiarised us all with Kyiv’s skyline. Many readers will therefore know about the colossal statue of a stern and rather butch maiden holding aloft a sword and shield. The Motherland monument is obviously big. But how big is big? And what is a colossus anyway?

In painting, bigger isn’t necessarily better. Only a fool would contend that scale makes Rembrandt’s Night Watch better than Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring. But in sculpture, size matters. Just as an orator must project his voice, a public monument must impose itself on space. In the intimate setting of the Palazzo Medici’s courtyard, the human scale of Donatello’s bronze David worked well. Michelangelo’s marble David, which was always intended for a public square, is over five metres tall. Michelangelo’s goal was not just to recreate the grace of ancient statuary but also to revive a dormant classical form: the colossus.

The Colossus of Rhodes, depicting the sun god Helios, was the most famous of these and supposedly the tallest. Though nothing survives of Helios, his reputed scale of 30 metres means he wasn’t made of stone. Beyond a certain size, only metal is strong enough to support itself. In 226 BC, that strength failed during an earthquake and the remains were plundered for scrap—the ultimate fate of most metal sculptures. But if Michelangelo restarted the race in 1504, David was soon dwarfed. Giambologna’s Apennine Colossus (c. 1580) is in Tuscany too. It is 11 metres tall, a crouched figure of a muscular, bearded deity, which despite its scale, blends into its pastoral surrounding.

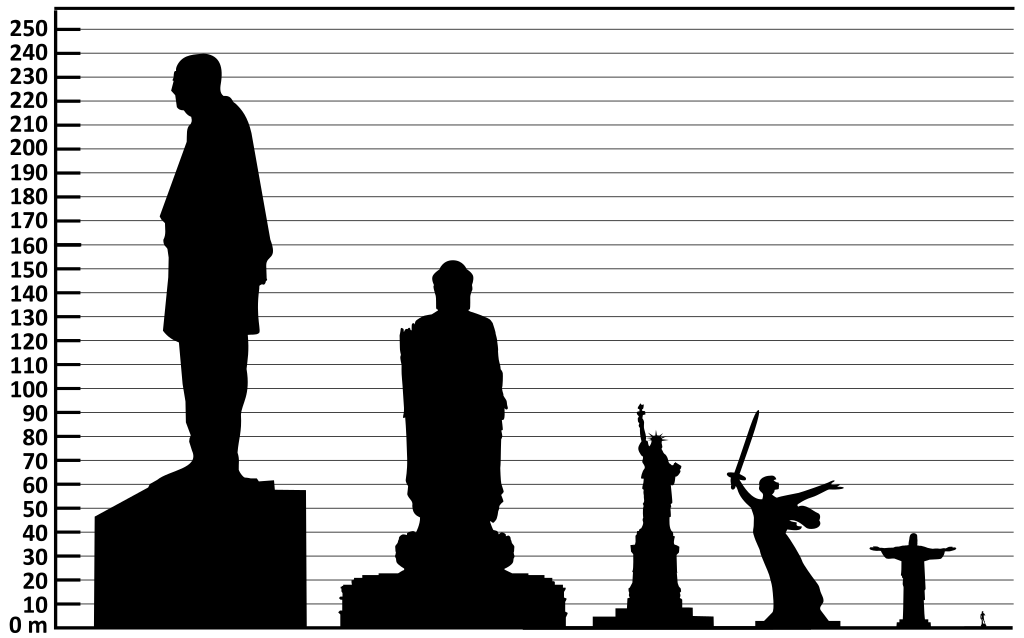

The colossus really found its oversized feet in the 19th century, the age of heroic engineers. When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, it was triumphantly decorated with Auguste Bartholdi’s 86-metre-high statue, Progress Carrying the Light to Asia. At least that was the plan. When the Khedive of Egypt saw the price, he balked. So, Bartholdi changed the statue’s costume and pitched her to New York. Bartholdi also halved the statue’s size and it’s a good thing that he did. While the French built the Statue of Liberty, as we now know her, the Americans were left to build the pedestal. Funds soon ran short, and the embarrassing hiatus only ended when the publisher Joseph Pulitzer raised $100,000 by public subscription.

Grasping the size of the titans we’re discussing is difficult. Lady Liberty’s lips, for example, are nearly a metre wide, and statues of this size require serious engineering. The bronze of Donatello’s David supports itself but a 46-metre-tall metal statue with a load-bearing surface would quickly pull itself apart. Lady Liberty’s internal armature was designed by Gustave Eiffel (yes, the tower guy). It’s effectively an iron truss tower with a secondary skeleton attached to the “skin.” This curtain wall construction allowed the skyscrapers sprouting in Manhattan to stay standing, and it let Lady Liberty, who was completed in 1886, expand a little on hot days and sway slightly in the wind.

Until 1967, capitalism’s capital stood tallest. Then Volgograd smashed New York’s record with The Motherland Calls, which is as tall as Lady Liberty and her pedestal put together. In a pose reminiscent of Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People, Yevgeny Vuchetich’s statue strides into the fray with sword aloft, beckoning patriots to follow. While much Soviet-era sculpture is stolid and bombastic, The Motherland Calls is passionate and inspiring. Built with prestressed reinforced concrete, her dynamic off-centre pose and the huge lateral load of her outstretched arm makes her engineering even more challenging than Lady Liberty’s. Got the message, comrade? Anything they can do, we can do better.

Politics encourages more giant-building than aesthetics. It’s not enough to celebrate our greatness, we want rivals to see. And what’s the harm in that? Sigmund Freud gave displacement activity a bad name but it’s better for everyone when military rivals build statues, race to the Moon, and cheat at the Olympics instead of fighting. Freud’s habit of comparing everything to you-know-what casts a long shadow, and the conversation about architecture hasn’t advanced much since. Norman Foster’s St Mary Axe building, generally known as “the Gherkin” by Londoners, has also been called the “Towering Innuendo.”

Some mockery is due. The colossus has appealed to tyrants from Pharaoh Amenhotep III to Kim Jong Un. The corruption associated with President Abdoulaye Wade of Senegal is exemplified in the African Renaissance Monument, Africa’s biggest statue as of 2010. Ten metres taller than the Statue of Liberty, it was built by a North Korean construction firm for $27 million. With characteristic chutzpa, Wade claimed that he deserved 35 percent of tourist profits since he came up with the idea.

In the former Soviet Bloc, the problem of what do with history’s leftovers is not abstract. Memento Park in Hungary and Grūtas Park (aka Stalin World) in Lithuania have vast collections of the toppled and unwanted statues of communist heroes. Shelly’s famous poem about a “traveller from an antique land” mocks despotic vanity. In an empty desert, the nameless traveller finds the fragments of a colossus below a pedestal inscribed, “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair.”

The Motherland monument of Ukraine is another Soviet leftover. That she has become a symbol of Kyiv’s defiance for Westerners is ironic. Sixty-two metres tall and made of steel, she was built in 1981. Look closer and you’ll see her shield is still decorated with a hammer and sickle. In the decade of escalating tension before the invasion, Ukraine’s parliament ordered the “decommunization” of all street names and statues. They didn’t get around to replacing The Motherland’s Soviet symbolism with a patriotic Ukrainian trident before the war started. So, she remains as she was, an ambiguous emblem of how Russia and Ukraine’s history is tragically entwined.

Across the border, in Moscow, towers one of the world’s strangest monuments. A 98-metre-high baroque wedding cake of a sculpture, it depicts Peter the Great standing, Gulliver-like, on a 17th-century frigate. Foreign Policy magazine—not previously known for their aesthetic judgement—called it one of the world’s ugliest statues. As the creator of what’s been called Ireland’s ugliest statue, I have a dog in this fight. The Peter the Great statue was erected in 1997—the chaotic year that a floundering Boris Yeltsin promoted an ambitious young fellow named Vladimir who got things done. The statue’s historical nostalgia and compositional incoherence suggest a country desperate to redefine itself, yearning for a strong man to steer them through the storm.

In our own lifetimes, the cliché linking tyrants to titans has become less accurate. Of the world’s top 10 tallest statues, a league now dominated by Asia, most are religious: Hindu deities, the odd Madonna, and Buddahs galore. Numbers two, three, and four—all built in the last 30 years—are Buddahs from China, Myanmar, and Japan. From an artistic point of view, this is regrettable. Aside from the Renaissance and Baroque eras, religious statues are dull. Their forms are conventional, their designs stereotyped. But creativity is not the point. Their very ubiquity suggests a general rejection of the homogenising influence of secular modernity. It’s a trend we also see, albeit on a more modest scale, in Europe: in 2010, Polish Catholics erected a 33-metre-tall statue of Christ the King.

If this trend makes Richard Dawkins despair, he may rejoice that the largest statue in the world depicts a mere mortal. If you’re as ill-informed as I am, you’ll have a vague idea that The Statue of Unity was built five years ago somewhere in India. I hadn’t a clue, until recently, who it depicted or who sculpted it. My ignorance possibly reflects a wider Western ignorance about the subcontinent. The statue will possibly remedy it. Either way, it’s another sign that India is a 21st-century superpower. Those who fear that we live in the era of the universal managerial state may worry that a man called the “patron saint of India’s civil servants” merits such an extravagant monument. It’s a statue of Sardar Patel (Sardar, means “chief”) who fought for independence with Gandhi and then became India’s Deputy Prime Minister.

Though mega-statues tend to have simplified forms, the 182-metre-tall (almost an eighth of a mile) statue of Patel is surprisingly naturalistic. The sculptor Ram V. Sutar, who is still alive and almost a hundred, grew up in a fragmented India, composed of hundreds of principalities. Patel was a sort of Indian Bismarck who persuaded their princes to join greater India. That he didn’t give them much choice is suggested by his other (and frankly cooler) nickname—the Iron Man of India.

Will someone next build a statue with its head in the clouds? It seems inevitable, but I hope not. The ambition to build bigger became, at some point, an end in itself, and subject to diminishing returns. Perhaps it’s a hangover of a religious upbringing—but there is surely something wrong when idols seek to annex “the high untrespassed sanctity of space.” The cautionary tale of the Tower of Babel still resonates during an age in which we everywhere run up against our limits.

The colossus must return to earth. British sculptor Laurence Edwards shows us how. His Suffolk Colossus is eight metres tall, not small but still approachable:

Absolutely love Yoxman, such an impressive presence in the landscape emerging from the Suffolk soil, by Suffolk artist https://t.co/DA6eYtOorB #Suffolk pic.twitter.com/RmMWjS98gN

— Heather Lomas (@Heather_Lomas) November 21, 2021

This primal totem of wyrd old England is the newest inhabitant of the little village of Yoxford. When the Yoxman appeared in 2021, his nudity caused a tabloid stir. “East Danglier” ran the Sun’s immortal headline. Rust coloured, standing solemnly in a green Anglo-Saxon landscape, vibrating with chthonic (a pretentious adjective that seems to be justified for once) power, the Yoxman isn’t intimidating. He simply is. He seems to be waiting for something. Perhaps the world to come to its senses. Whatever it is, the Yoxman is an eloquent reminder that the artistic possibilities of this ancient form are also colossal.