Art and Culture

The Dualism of Duluoz

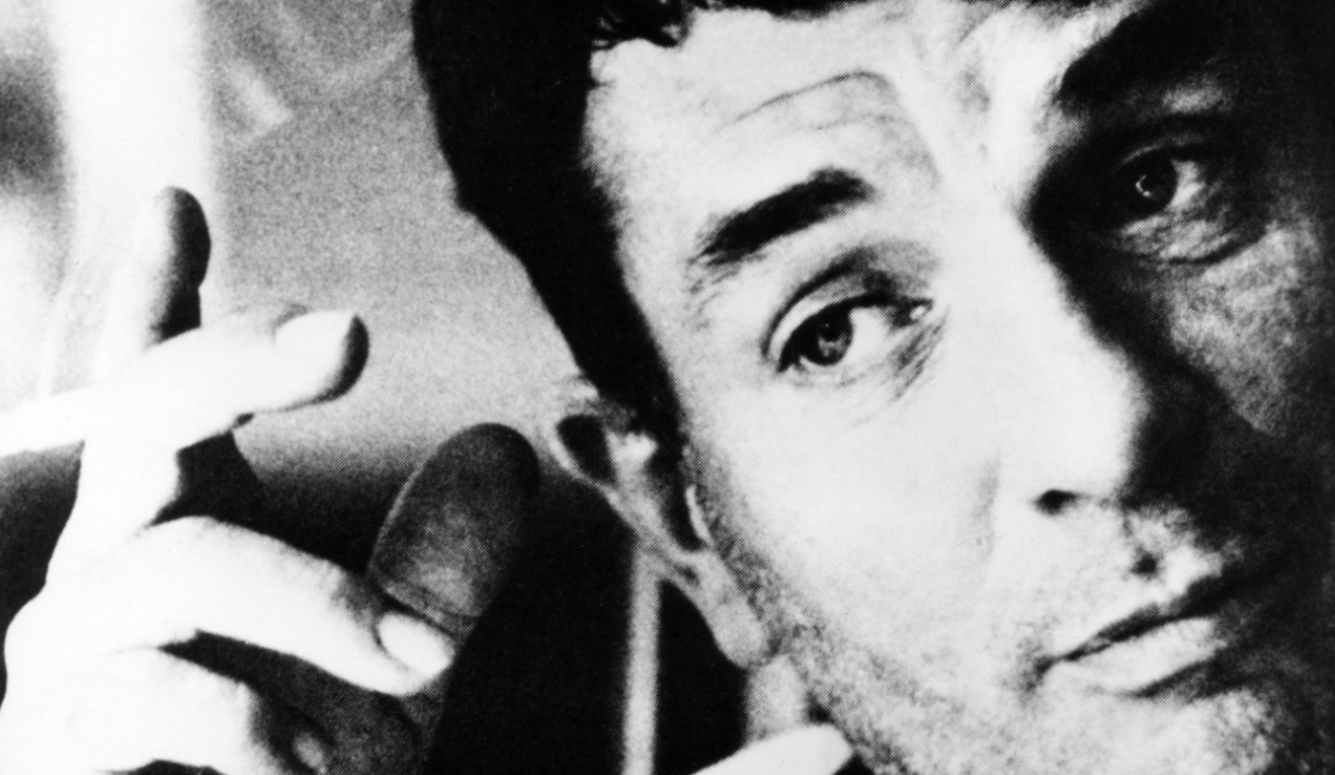

An eagerly awaited new edition of Gerald Nicosia’s splendid Kerouac biography provides the definitive portrait of a great artist and a profoundly troubled man.

A Review of Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac by Gerald Nicosia, 841 pages, Noodlebrain Press (June 2023)

Gerald Nicosia’s Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac was first published in 1983 to universal acclaim. Kerouac’s Beat Generation peers, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Michael McClure, and John Clellon Holmes, all praised it for accurately capturing its subject. Countless Beat scholars have also applauded it, including Barry Miles, who called it “the greatest work of Kerouac scholarship there is.” Even today, after the publication of numerous other Kerouac biographies, it is still widely regarded as the finest, and the announcement that it was to be reprinted was greeted with much excitement.

This, of course, raises the question of why anyone would bother to review a revised edition of a book first published 40 years ago. The answer is twofold: First, this is a significantly expanded edition, reaching nearly 900 pages; and second, Memory Babe has been out of print for 20 of those 40 years. Memory Babe’s publication troubles could fill a book by themselves, and they nearly have. Nicosia’s Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century (2019) covers much of the author’s struggles to keep Memory Babe in the public eye.

After Kerouac died in 1969, his literary estate was inherited by his mother, Gabrielle, who then passed away in 1973. In his final years, Kerouac had wed a woman named Stella Sampas solely to take care of Gabrielle, but it was a loveless marriage, and shortly before he died, he planned to divorce her. After his death, Stella and her siblings forged Gabrielle’s signature on a will that bequeathed the entire estate to them, and since 1973 the Sampas family has profited mightily from its ownership of what Nicosia claims is “the most lucrative literary estate of the twentieth century.” (Despite the forgery being proved in 2009, a statute of limitations prevented the estate from being passed to any of Kerouac’s few surviving descendants.)

In his preface to the new edition of Memory Babe, Nicosia refers to the estate drama as “the Kerouac Wars,” and it is his role in the bitter squabble that caused his biography to become so controversial. Early in the debacle, Nicosia aligned himself with Jan Kerouac—Jack’s daughter with his second wife Joan Haverty. A writer herself, Jan attempted to wrest control of her family estate from the Sampases, but was thwarted, and like her father, she died at a tragically young age. The horrific details of her treatment by the Sampas family are provided in The Last Quarter Century. Having championed her cause, Nicosia was, in his words, “targeted for reprisal” by the estate. He says he was blacklisted from almost all Kerouac-related events and publications, and that John Sampas, self-appointed literary executor, even issued Viking Books with an ultimatum: drop Nicosia’s biography or we’ll take Kerouac’s books elsewhere.

And so Memory Babe was dropped. It found other homes over the years, but the Sampas clan kept up their legal challenges until it drifted into limbo. They ensured that Nicosia’s name was redacted from officially sanctioned publications, even when his research was used, and they banned him from conferences and film appearances. Industry-wide, he became a black sheep, and since 2001, his definitive biography has been out of print. It remained the text of preference for many Beat scholars and could still be found on numerous bookshelves, but those were old editions, and as the field of Beat studies exploded, there has been much more to add to a full appraisal of the Kerouac legacy.

The 2023 edition of Memory Babe, published by a small California press, duly includes newly uncovered information on Kerouac’s origins and childhood, an expanded assessment of his 1959 novel Visions of Cody, and much more about his final years. It also incorporates the famed “Joan Anderson letter.” In Beat circles, this letter was an almost mythical artifact until its discovery in 2014 sent a shockwave through the Beat community. The letter was written by Neal Cassady and sent to Jack Kerouac, who was so inspired by it that he re-wrote On the Road, incorporating much of Cassady’s style. Nicosia explains the various ways in which this letter shaped Kerouac’s prose, noting that “its relationship to Kerouac’s own writing is immense, uncanny, and at times even a little scary. Jack not only swallowed the letter whole, but came out of the process speaking to a great extent in Cassady’s own voice.”

Nicosia updates us on all these developments by prefacing the new edition with a variety of documents. These mostly detail the book’s publication woes and Nicosia’s various struggles with the Sampases. It’s a damning critical assessment and constitutes the author’s reprisals for the years he spent effectively shunned. Nicosia is a fiery character, and he does not hold back. In addition to summarising the crimes of the Sampas family, he excoriates celebrated Beat scholar Ann Charters for colluding with them to remove his name from Kerouac’s collected letters—an accusation, essentially, of plagiarism.

He then attacks presidential scholar Douglas Brinkley for using Kerouac to build his own reputation and for butchering the editing of Windblown World: The Journals of Jack Kerouac 1947–1954. Nicosia calls Brinkley’s work “disturbingly careless and at times stunningly bad” (a charge that could equally be levelled at Brinkley for his handling of Hunter S. Thompson’s estate). He then provides “an inglorious list of editors,” whom he believes were handpicked by the Sampases and failed in their efforts, before complaining about the posthumous publication of various sub-par books that have done little for Kerouac’s literary reputation.

This probably sounds like a bitter and extended piece of griping, and in a sense it is. But given the history, one can hardly blame Nicosia for taking the opportunity presented by this belated reissue to settle some scores and straighten out the record. Given his work and its significance, it is hardly surprising that he felt aggrieved at the substandard work produced by those who have worked with the Sampas family on profitable Kerouac projects, often using Nicosia’s research without credit. But still, this long, angry tract full of personal grudges bumps up awkwardly against the book that follows—a painstakingly researched, lovingly told, and meticulously detailed life of Jack Kerouac.

Kerouac is one of those figures whom everyone seems to think they know. One of the most famous American writers of the 20th century, he was controversial in his own lifetime and remains mysterious even now. In Kerouac circles, his life and work are fiercely debated while myths continue to abound among the uninformed. The Internet is awash with butchered quotes, unsubstantiated rumours, and quibbles over Kerouac’s religious and political leanings. To most people, he was a “beatnik” writer, but this is a misnomer—the Beat Generation pre-dated the beatniks, who were a fad that came about in the wake of the former’s literary innovations.

Understanding Kerouac has never been easy, even for those of us who have read all his novels and poems and letters, not to mention the numerous biographies and critical assessments. To paraphrase Nicosia in one of his various prefaces: the more you learn about Kerouac, the less you seem to know. This is not because he was necessarily enigmatic—Kerouac was famously confessional in his writing. Rather, it is because there always seemed to be at least two Jack Kerouacs. And this is where many biographers falter—they invariably emphasise one Kerouac at the expense of the other. Nicosia, however, is unafraid to show his subject as he was—dualistic, divided, and difficult.

The life of Jack Kerouac was tragic. In childhood and adulthood alike, he was profoundly shy and compensated with an off-putting boisterousness. He struggled to cope with the world around him, be it the frustrating invisibility of being a struggling artist or the crushing infamy that he ultimately earned with his numerous Beat novels. He was intelligent and creative, delicate and artistic, handsome and athletic. Although his early efforts at writing showed great promise, he seemed more likely to become a successful American football player and his sporting heroics were frequently reported in newspapers.

At home, however, he was coddled by an oppressively attentive mother who bathed him into his teens and instilled in him a Catholic guilt and Oedipal complex that would ensure he never found lasting love. On top of all this was a terrible sense of inadequacy, fed in no small part by his mother telling him, after the death of his brother, that the wrong son had perished. This troubling mother-son relationship persists throughout Memory Babe, and for good reason. It was almost certainly the root of his paralysing duality.

In the chapters devoted to his younger years, Nicosia depicts a man filled with boundless enthusiasm, who flits from place to place, frustrating those around him with his inability to commit to anything. “[T]here were never enough activities to work off his nervous energy,” Nicosia writes. “Jack had no desire to moon poetically over the tragedy of life. Rather, his instinct was to outrun it, to lose it in the oblivion of spent energy, while searching for new and possibly more hopeful experiences.” He jumped frenetically from girl to girl, friend to friend, and experience to experience. During World War II, he joined the Merchant Marines and shipped out on the SS Dorchester for what he imagined would be a romantic voyage fraught with danger. When his ship was attacked by a German submarine, it helped him to realise “that most men who die in war have no real desire to harm one another.” This was to inform his lifelong pacifism. Though he was often alienated, in his younger years, he felt a deep connection to his fellow man—a sense that somehow, in spite of all our differences, humanity is united.

Shortly after he jumped ship in New York, he learned that the Dorchester had been sunk. Seven hundred lives were lost, including at least one of his friends. This was not the first time he had encountered death, and loss is a constant theme in this book. From Kerouac’s friends to his family, death was something that seemed to surround him. His brother Gerard died when Jack was a small boy, and he lost his father when he was still a young man. Friends like Bill Cannastra and Joan Vollmer would die in tragic, reckless accidents. Elsewhere, there were suicides and overdoses that left him scarred and perhaps afflicted with survivor’s guilt. His world was filled with ghosts and visions and all of this would emerge in his writing.

Kerouac’s restlessness and inquisitiveness saw him venture progressively further beyond his New England roots, curious about everything. He was enamoured of black culture and developed a particular affinity for jazz that eventually inspired his freewheeling literary style. At Columbia University, which he attended on a football scholarship, it was not books that grabbed his interest but a circle of friends including Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. Always in pursuit of “kicks,” he drank heavily, experimented sexually with both men and women, and tried many kinds of drugs.

This desperate pursuit of experience fuelled his writing. On one of his Merchant Marine voyages, he decided to embark upon a Proustian work comprising his whole life—“The Duluoz Legend”—and he pursued the project with fervour. Almost all of his novels can be read as chapters in this epic series, with himself at the centre, often going by the name Jack Duluoz. Over the years, his attitude towards writing would change, but for much of his life he wrote prolifically, churning out books at an astonishing rate, attempting to capture experiences, conversations, and people that he encountered. He used Benzedrine to fuel some of these writing sessions, sitting at a desk for hours or days at a time, typing so fast that the bell on his typewriter sounded like an alarm clock. He was famous for being fast and accurate in his typing and also for his memory—“Memory Babe” was a childhood nickname. He could reproduce whole conversations, even drunken ones, and could recall the minutiae of his early years in astounding detail.

Kerouac was so prolific that the chapters of Memory Babe covering his most productive years are filled with a dizzying array of titles. Not all of these planned books were completed and some were only published after his death (to fill the Sampas coffers, Nicosia tells us). Nevertheless, he produced a remarkable body of work, much of which was completed before he became famous. Such was the extent of his productivity in the late 1940s and early ’50s that almost all of his best books were already written by the time his breakthrough novel, On the Road, was published in 1957. Some years, he would produce three full novels, famously completing whole drafts in a matter of days, sometimes on a single roll of paper.

When Kerouac published The Town and the City in 1950, it was not the great success he had hoped for. Nor did it quite capture his artistic vision. After its publication, he laboured for years to ensure that his next book would be in his own voice, but most of his work was so innovative that it was hard to sell. When the Beat writers finally gained some recognition, he felt as though he was still languishing in obscurity. Though he feared fame, he yearned for it and for the adoration—not to mention the financial stability—he believed it would bring him. Alas, like many great artists, he was ahead of his time and would not be properly understood or appreciated until after his death.

Some people still struggle with Kerouac’s work today. A persistent criticism is that he was an undisciplined writer, speed-typing careless screeds about his deviant friends. From Truman Capote’s bitchy quip about his writing being nothing more than “typing” to quibbles over punctuation and morality, Kerouac is often derided as a sloppy and careless venerator of sociopaths, criminals, and other ne’er-do-wells. Nicosia shows just how untrue and unfair that characterisation is. Kerouac’s writing style was painstakingly developed. He studied literature and strove to incorporate jazz and American vernacular into what was a deliberate hybrid of poetry and prose.

We should also remember that English was not his native tongue. Raised in a French-speaking household, Kerouac learned the sounds of English words before he understood their meanings, resulting in an awareness of the musicality of language that few writers possess. There are points in his work where he seems to be producing gibberish, but like James Joyce, these passages were always carefully composed. He was criticised for his spontaneous prose and for writing On the Road in a single burst, but he always re-wrote extensively. The aim of that first frenzied draft was to capture something of his subconscious. Those who think On the Road was just an enthusiastic outpouring of words would do well to read the chapters of Memory Babe devoted to its composition, which stretched over the better part of a decade, and underwent constant revisions of style, theme, and plot.

Memory Babe is subtitled a “critical biography” because Nicosia devotes various chapters to analysing Kerouac’s books and poems. Here, he deftly picks apart Kerouac’s writing to explain his craftsmanship, pointing out repeated words (each book has a different set, which function almost as mantras) and colour symbolism. He explains how Kerouac used seasons and imagery with impressive subtlety and how his work was infused with religious allegory. He shows Kerouac’s gift for parody—even self-parody—and his use of techniques that fold time and space to communicate his belief in the universality of human experience. And he manages to do all this without descending into impenetrable academic jargon. While Nicosia is critical of some of Kerouac’s lesser works, his analyses help us to understand why Kerouac was such an inventive and important writer.

The longest of these critical chapters is devoted to Visions of Cody, which Nicosia appears to think is Kerouac’s finest book. If On the Road was a commercially viable study of Kerouac’s muse, Neal Cassady, Visions of Cody was the more challenging (Nicosia argues “postmodernist”) version in Kerouac’s more authentic voice. Kerouac called it “a vertical, metaphysical study of Cody’s [Neal’s] character and its relationship to the general ‘America.’” The complex friendship between these two men is central to Memory Babe. They did not initially get along with one another. “Each of them felt inferior in the other’s presence,” Nicosia explains, “and, sadly, neither realized how much the other really liked him.” Cassady was jealous that Kerouac could write and Kerouac was jealous of Cassady for being so outgoing and easy with others. Cassady was an infamous ladies’ man while the painfully shy Kerouac struggled with women, even when they were attracted to him.

In spite of their friendship and the inspiration that Cassady’s antics provided for some of the greatest literature of the era, the story of their relationship is nonetheless depressing. Cassady was clearly an abuser—physically and emotionally scarring people, and destroying lives with casual impunity. He disappointed Kerouac frequently, but not as much as he disappointed his various wives and girlfriends. In particularly disturbing sections of Visions of Cody, we find him attempting to sleep with a nine-year-old Mexican girl, only to fail and pay a 12-year-old for sex instead. Somehow, Kerouac admires this kind of thing, not because he considers it decent behaviour but because Neal is true to himself and truth is, for Kerouac, of utmost importance. Still, despite an almost fraternal bond, the two men frequently fell out and eventually drifted apart. Cassady, like Ginsberg and Burroughs, went on to collaborate with artists of subsequent generations and countercultural movements, while Kerouac stayed at home with his mother, drinking himself to death.

Whilst less reprehensible in terms of attitude and behaviour than Cassady, Kerouac was by no means a saint and Memory Babe reveals a catalogue of pretty abhorrent conduct. Above all else, there is his sexism. This was no mere product-of-the-times sexism but an outright loathing of women. Perhaps stemming from his relationship with his mother, Kerouac’s life was a long process of falling in love with women whom he nevertheless hated and verbally abused. He had no respect for women as anything other than domestic servants and would tell them flatly that their opinions were not of any importance.

And despite Kerouac’s youthful openness and his love of black people and culture, in his later years, he regressed into tawdry racism and antisemitism. In one notable passage late in the book, Kerouac takes his young nephew to burn a cross in a black neighbourhood. Elsewhere, he screams racial slurs in black bars. There are efforts from Nicosia and various of Kerouac’s friends to justify some of his hateful behaviour. His antisemitism was, Allen Ginsberg suggested, just a means of testing people to see if he could trust them, but this apologism is not supported by most of the evidence. Meanwhile, his racism, we are told, stemmed from insecurity about the size of his penis. Still, while Nicosia often attempts to explain Kerouac’s attitudes, he does not hide or defend anything—another reason his book so offended the Sampas estate, which had excised much of the sexism and racism from Kerouac’s letters.

In the end, Kerouac’s racism is probably best understood as another of his uncountable paradoxes—evidence of the startling dualism in the mind of this challenging figure. He retreated into an ignorant and hatefully reactionary kind of conservatism in his later years, babbling drunkenly like a paranoid crank in private, in public, and even during disastrous TV appearances. The image he projected in his later years could hardly have been further from the loving, open, and explorative young man he had once been. It was obvious he was approaching the end of a long and tragic decline.

Perhaps if he had been given the respect he was due and treated like the major American author he was, things would have turned out differently. But that never happened. Nicosia tells us that just three days after On the Road was published, “the Sunday Times carried David Dempsey’s review of the novel, ‘In Pursuit of Kicks.’ It marked a turning of public opinion against Kerouac that was never reversed in his lifetime.” From that moment on, Kerouac was cursed by the cult of celebrity but never taken seriously. His novels were repeatedly mischaracterised by ignorant reviewers. “No one had the courage,” Nicosia explains, “to say they simply didn’t understand.” Instead, they focused on the salacious details—the sex and the drugs—and overlooked the poetic brilliance. They savaged him for breaking the rules of punctuation, calling him careless and undisciplined, yet Kerouac had written a well-crafted traditional novel many years before On the Road. Like Picasso, he had learned his art in the conventional sense, but his genius compelled him to break the rules and do something so profoundly new that few could grasp it.

These criticisms resurfaced with each new book he published, driving him further and further into drunken bitterness. It was as though reviewers awaited each novel, revelling in the opportunity to sling insults at an easy target. In time, Kerouac’s productivity faded, and as alcohol and a number of head injuries from drunken accidents diminished his ability to defend himself, he became a laughing stock. Retreating to his childhood home of Lowell, Massachusetts, he became the village idiot, constantly being booted out of bars and picked up by the police, the whole town watching and laughing as he drank himself to death.

In 1969, a year after Neal Cassady died of exposure on a railway line in Mexico, Jack Kerouac began coughing up blood at his home in Florida. Despite numerous transfusions, he bled out and died on October 21st. Few were surprised. His deterioration had been almost two decades in the making, his decline always driven by the dualism that tormented him. It was his oesophagus that haemorrhaged, but he may as well have been ripped in half.

Kerouac was afforded little respect in his lifetime and only a few scholars bothered to poke around in search of meaning while he was still around. However, in the years that followed his death, people like Nicosia began to reassess his legacy, showing that he was no beatnik, no hippie, no angry young hoodlum writer. He was a true artist and one of the great voices in American letters. For all the legal wrangling and public bickering, it is clear that countless parties remain interested in keeping Kerouac in the public eye and poring over his work in search of meaning, of which there is plenty to be studied. His complexity was not only a matter of character, it was also a matter of artistic composition.

Of all the efforts to reinvestigate this complicated figure, few publications come close to the significance of Memory Babe. It is truly a privilege to see it in print again after it languished, like its subject, in obscurity for so long.

Note: Memory Babe was scheduled for publication in early 2022 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Jack Kerouac’s birth. Due to various health issues, the author was unable to promote his book, so the release was postponed until June 1st, 2023.