Politics

Uncomfortable History

Grappling with Western misdeeds does not require us turn indigenous tribes into pious exemplars of moral instruction.

A review of Indigenous Continent by Pekka Hämäläinen, 592 pages, Liveright (September 2022)

The Freudian concept known as “reaction formation” refers to a psychological defense mechanism against guilt. It occurs when an individual responds to a shame-inducing instinct with an overcorrection. Much of modern American history appears to be in the grip of reaction formation. Mortification at the developed West’s historical misdeeds has produced a utopian narrative of indigenous worlds typified by matriarchy, cooperation, pacifism, and gender fluidity. That no such world ever existed is beside the point; much of history is narrated to suit the proclivities of the audience, not to tell the truth about what actually happened.

This seems to be specifically true for our understanding of American Indian history. The violent migration of Europeans to the New World was very much like violent migrations throughout history and across cultures, most likely including successive waves of North American Indians (though the history there is murky). Yet instead of understanding these events in the context of larger historical patterns, the Indian Wars are cast as a morality tale in the manner of Howard Zinn, in which the actions of the European settlers are represented as uniquely reprehensible. This fantasy may be an inversion of past jingoistic and racist caricatures of American Indians as “savages,” but it is not more historically accurate.

I thought about this a lot as I read Pekka Hämäläinen’s fascinating and controversial new history of North American Indians, Indigenous Continent. Told largely from the perspective of the natives, Hämäläinen covers the centuries from the arrival of Europeans in North America through to the final subjugation of the last tribes in the late 19th century. It’s a gripping history, but watching the author attempt to come to terms with the history he is telling also makes for fascinating psychological analysis.

Hämäläinen is clearly sympathetic to the Indians. Indeed, the Europeans in his story tend to be portrayed as dirty, bumbling idiots who are repeatedly outwitted until, well, they’re not. Hämäläinen leans into this interpretation a bit much, and as a psychologist, I was as intrigued by how he grapples with history as much as the historical evidence. His sympathy for the Indians is evidently in tension with his unwillingness to distort the facts. For this, I admire him, since history is often distorted to suit the needs of political and academic elites of any given period. But the author’s attempts to square the historical facts with the moral lessons he hopes to impart leads him into contradiction and incoherence.

On one page, Hämäläinen assures the reader that Indians were egalitarian, only to follow that assurance with numerous examples of how that was not true. This inconsistency surfaces early in the book, when Hämäläinen informs us that the Taino Indians encountered by Columbus were “hierarchical” and “stratified.” Elsewhere, we are told that Native Americans were generally respectful of women (the word “matrilineal” is asked to do some heavy lifting here), but we are also provided with specific examples of tribes keeping women as sex slaves, some of whom were brutally abused by tribe members.

Indeed, although the word “captive” makes a lot of appearances in the book, it is selectively employed. When Europeans take people unwillingly to harsh work environments, or to be sold to others, these victims are called “slaves.” But when American Indians do the same thing, Hämäläinen euphemistically describes those victims as “captives.” In fact, a number of tribes were energetic participants in the trade of other indigenous people, selling slaves to other tribes and to Europeans. Although Hämäläinen shows an admirable willingness to discuss such practices, his discomfort is palpable.

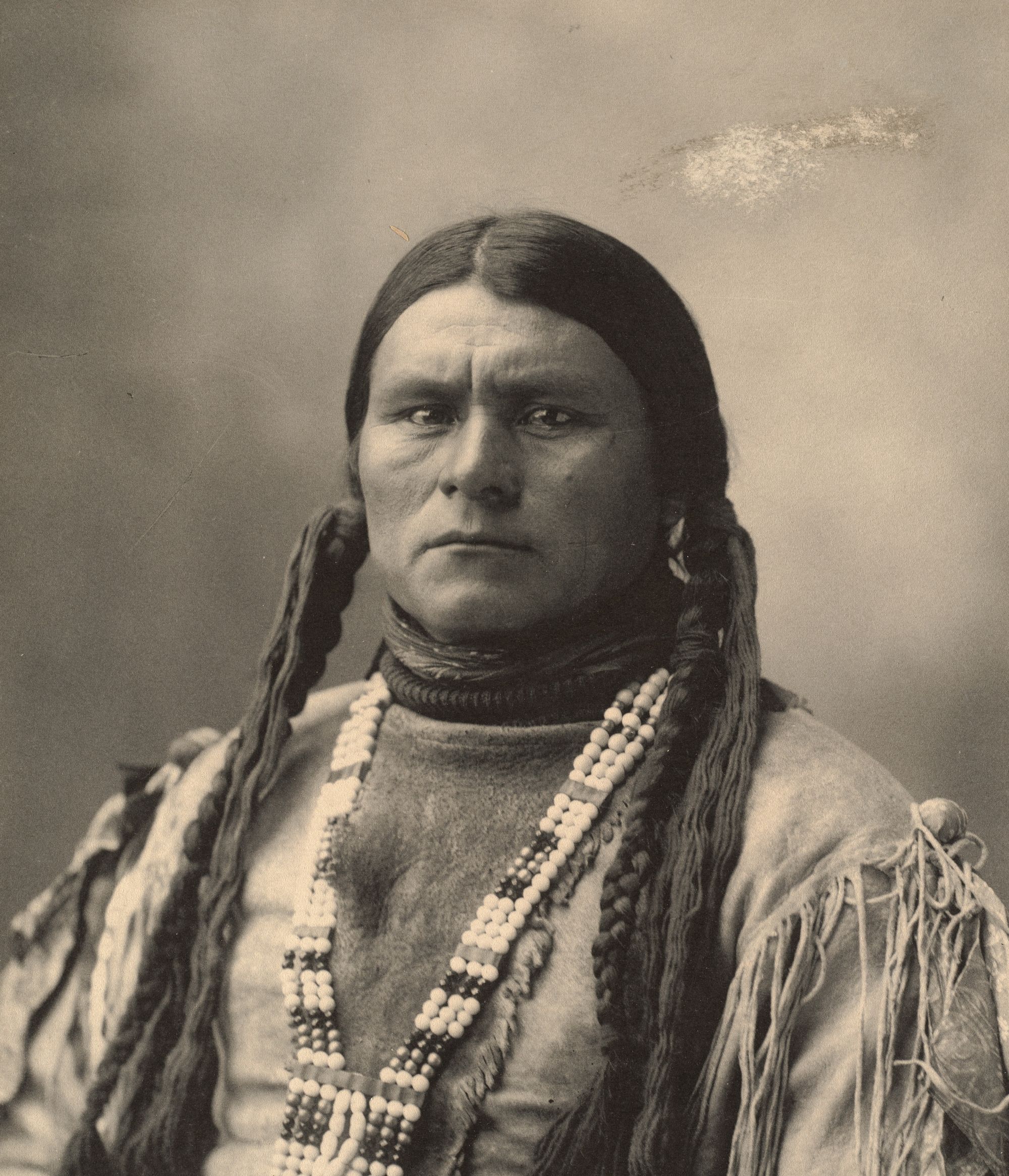

Rather than revealing the cultural chasm between indigenous people and Europeans, the historical record teaches us just how similar they were. Each vied for status and power, kept slaves, engaged in genocide against neighboring groups, mistreated women, indulged ethnocentrism, and so on. Tribes or confederations such as the Iroquois, Sioux, or Comanche were violent warrior cultures that recall the Spartans. This observation isn’t intended to denigrate Native Americans, it is simply evidence of our shared (if profoundly flawed) humanity.

What Europeans did to American Indians was often terrible, but Indians gave as good as they got, both to Europeans and each other. These stories are similar to those the world over—we are all equally capable of great horrors and cruelty and history provides few examples of morally unambiguous heroes. Embracing this universalist truth can help us to move past the morality tales so often told in the guise of history and discard a misbegotten and ultimately selfish indulgence in self-flagellation.

This has always been the problem with the Howard Zinn school of history. Zinn’s history of the US resembles a biography written by a bitter former spouse. In lieu of a nuanced and accurate historical account it offers a deliberate slander of our own culture. The result is at once self-indulgent and self-pitying. A balanced account must not flinch from examining our historical mistakes and misdeeds and those of others, but the modern approach to history has too often become a neurotic wallowing in half-truths of our own failures. The corresponding utopian fantasies of other cultures more closely resemble the morality play of a Tolkien novel than the more complex experiences of people who actually lived on Earth.

As UK-based IEA economist Kristian Niemietz recently observed in a short Twitter thread about “anti-Britishness,” signalling disgust at our own culture and history has little to do with truth or helping marginalized communities. Rather, it is a way to advertise the superficial cleverness of radical self-criticism. By castigating the United States on social media or with our K12 or university students, we can flatter our moral egos without needing to donate money or time to communities in need. It fosters division and the main beneficiaries are not Native Americans or other marginalized groups, but whoever is collecting likes and followers online.

We can do better than this. US history should be clear and accurate about the US’s misdeeds, but we should also acknowledge that the US overcame its faults to become a beacon for progress. In the same way, we should highlight the wonderful culture, arts, religion, and so on of American Indians without turning them into pious exemplars of pastoral innocence and moral instruction. Our “ethnic studies” curricula too often lapse into propaganda designed to indict and shame the West and all its works. People and cultures are complex. If students were permitted to understand that human failings are universal but can be overcome, it might help to alleviate the depression and anxiety of those unjustly burdened by the sins of their ancestors.

Indigenous Continent strives to provide an honest and fascinating account of historical complexity at a time when progressive activism is tightening its grip on the search for disinterested truth. But it also helps us to see, firsthand, how uncomfortable historians working in this environment are with the inconvenient truth of the stories they have to tell.