The concept of iatrogenesis, native to medicine, describes misfortunes that would not occur but for one’s interaction with medicine itself. For example, the case of COVID you catch in the doctor’s waiting room or the elective surgery that impinges on a vein, which throws a clot, causing a stroke. Shockingly, medical iatrogenesis is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide.

Journalism’s iatrogenic damage may be less dramatic, but it is surely more pervasive because there is no escape from exposure. Avoid consuming news and you still will be passively subject to the media’s effect on your environment. Even for a long-time media whistleblower like Bernard Goldberg, such epiphanies can take a while to crystalize. Here’s the operative passage of a recent column:

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about my profession. I always knew that journalism was fundamentally a pursuit of the negative, that we mainly report about bad things that happen, but I never gave much thought to how all that negativity affects us—it affects how we see things, especially how we see the country we live in.

It’s not just that most news is bad news and that bad news is inherently more compelling. It’s that the news frequently misrepresents reality, setting in motion a cascade of tangible and intangible harms. For journalism is not the passive entity many think it is—it alters life by observing it. While neither Goldberg nor any other media denizen is likely to allege that journalism does more harm than good, it surely does too much harm, and that harm is increasing.

Of tide and tumult

The potency of advertising, especially saturation advertising, is now beyond reasonable dispute. Tide may or may not be your best option for keeping clothes clean and springtime fresh, but it’s the top-selling detergent in the US by a wide margin, doubling its nearest competitor in revenues—and Procter & Gamble has spent a fortune to engineer that outcome and keep Tide’s orange trade dress front-of-mind for American housewives.

Today’s 24/7 news cycle is, by its nature, a saturation ad campaign for the zeitgeist, the world in which we supposedly live. This is particularly noticeable in coverage of major themes like crime, race, and politics, which is brassy and unrelenting and helps to cement our perception of Truth. America’s flagship all-news radio station, New York’s WINS, says this explicitly (albeit erroneously) in its famous slogan: “You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world.”

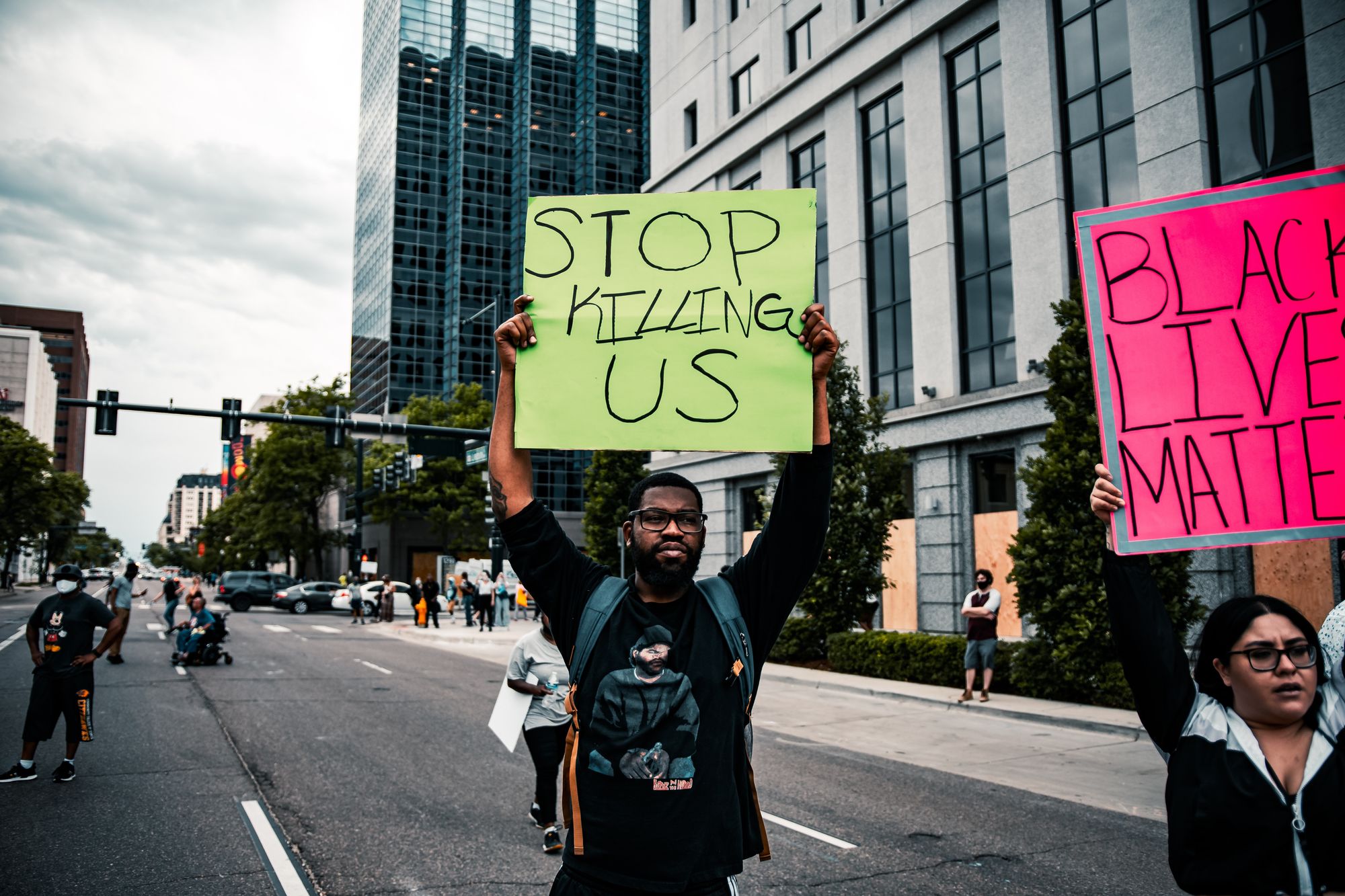

As print journalism gave way to broadcast, and the news business became more advertising-like, it acquired exponentially more psychological gravitas. There is a world of difference between (1) writing “the US is using the incendiary substance napalm to denude the forests where Viet Cong sharpshooters hide” and (2) showing a scalded little girl running along a road with her clothes burned off her naked body. The first is a description, the second is an indelible atrocity. Similarly, there is a world of difference between (1) saying “a black man died in police custody” and (2) showing the full, agonizing 9 minutes and 29 seconds of the George Floyd video over and over again for months. The latter is the journalistic equivalent of P&G’s $10 billion saturation ad spend.

None of which would matter much if journalism did indeed give us “our world.” But journalism covers life in terms of what it isn’t. The iconic WINS slogan has it backwards. In its most basic sense, newsworthiness is built on atypicality—Man Bites Dog is more newsworthy than the reverse. Or as the newsroom maxim has it, “Nobody writes stories about the planes that land.” So when a plane goes down, the media coverage is giving you a high-resolution snapshot of a vanishingly rare event. On any normal day, around 28,500 commercial flights take off, fly to their destination, and land without incident.

An event like 9/11 may be momentous, even epochal, but it is not everyday life. By definition. It is a negative image of life in both the photographic and tonal senses. Every day, the news media provide a smorgasbord of stories that, despite their disparate topics, blend into a common theme: They are those rare instances in which, metaphorically speaking, the plane did not land.

Nationwide, the chances that you will be shot to death in the US this year are 0.006 percent (although that figure will vary from state to state and neighborhood to neighborhood). That is, six-thousandths of one percent. As for “assault rifles” like the AR-15, a firearm with which reporting on this topic is particularly preoccupied, reliable data are hard to come by. Such weapons are lumped in with all rifles in the FBI’s accounting, but rifles as a class figured in just three percent of the 19,384 gun homicides in 2020—about 580 deaths. Inasmuch as assault weapons constitute just part of the category, you had a less than one in 570,000 chance of being killed with such a firearm that year.

“Between 2007 and 2017,” notes the Foundation for Economic Freedom, “nearly 1,700 people were murdered with a knife or sharp object per year. That’s almost four times the number of people murdered by an assailant with any sort of rifle” [emphasis in original]. If it does not feel that way, it’s because of the nightly sturm und drang on CNN et al, which unfolds as an unending cavalcade of gun homicides, often with an “AR-15-style” weapon.

In 2007, the Virginia Tech mass shooting alone claimed the lives of 33 people (including the shooter). But if we set this anomaly aside, between 2001 and 2018, annual homicides on American college campuses, which collectively serve some 17.9 million students, ranged between 11 (2014) and 28 (2015). This puts the average risk of being murdered at about one in 1.2 million, far lower than many other risks we assume in daily life. Nevertheless, wall-to-wall coverage of events like the 2022 massacre of four students in Idaho yield polls in which over 82 percent of students say they fear for their safety on campus.

Several reasons beyond the sheer power of advertising explain why we don’t see the news as a walking tour through marginalia. When we consume journalism, the true prevalence of reported phenomena remains unknown to us. We’re inclined to take what we see at face value; if a story made the news it is newsworthy, ipso facto. This can produce availability bias, which leads us to rely upon easily recalled examples when making decisions and assume that those examples are representative when they may not be.

Further, ratings and other imperatives demand that sensational stories crowd out all others. So what ends up on the news is tantalizing and memorable (“If it bleeds, it leads”). Finally, newspeople work hard to dispel the notion that they trade in trivia, loath as they are to diminish their status as cultural shamans. Skilled at heightening immediacy and drama, anchors make everything seem epochal or part of some “bigger story.”

The extent of this distortive effect became clear in a 2019 Gallup poll that surveyed respondents on crime. Just 13 percent rated crime in their own neighborhoods as “very serious” or “extremely serious.” Yet 52 percent deemed crime in America to be a whole “very serious” or “extremely serious.” If crime were as rampant nationally as respondents believed it to be, how could some 87 percent of respondents feel safe in their “own neighborhoods”? Such a skew can only be understood in terms of the macro impressions consumers infer from the news.

Media coverage makes obscurity seem like ubiquity. The endemic nature of this circumstance means that, even at its best, journalism will give rise to fallacious assumptions about reality. Worse, today’s activist journalists don’t leave that to chance. But I won’t dispense another jeremiad about news bias, which has been amply litigated in this space and elsewhere. I want to focus here on the impact of these misleading visions of life.

Over-coverage of obscure risks, in particular, magnifies those risks in the public mind, sparking avoidance behaviors and other adaptations. Terrify American consumers over an illusory Mad Cow “outbreak” and even hamburger fanatics will stop buying hashed meat. Hype the dangers posed by a deer tick that turned up somewhere and families cancel much-anticipated vacations to national parks.

Stories about one-off occurrences can restitch the fabric of American life. A recent web search of the term “trans swimmer” returned 250 million hits, yet the first dozen pages were almost exclusively devoted to a single individual, Lia Thomas. By my estimation, every major media organization ran dozens of stories on Thomas. Just Thomas. That media furor sparked all manner of social discord and even legislation, widening the chasm between people already self-sorted into tribes. All this due to stories about one of 330 million Americans.

The simplistic, anecdotal coverage of the cultural divide, with its overwrought sagas of Karens versus women of color or Christian homophobes versus drag queens, undermines cohesion and makes people more likely to retreat into their echo chambers.

Death by media

Today’s saturation coverage of mental health and American hopelessness is unprecedented. Thinkpieces and news reports brim with hotline numbers. Celebs record PSAs urging self-care and therapy. And yet suicide is an intractable phenomenon, with rates worsening in almost every state in recent years. How can this be? Psychologists believe that no matter what the media say about suicide, the coverage itself is effectively advertising death as an option. The more you cover it, the more tempting it becomes.

The suicide-by-hanging of Robin Williams in early August 2014 occasioned a tsunami of media coverage and attendant handwringing. In the ensuing four months, America saw a nearly 10 percent increase in suicides—an additional 1,841 deaths over the expected base rate. As a researcher told CNN, “We found both a rapid increase in suicides in August 2014, specifically suffocation suicides, that paralleled the time and method of Williams’ death.” Extensive studies are increasingly resolving into settled science: The CDC now issues pointed bulletins urging caution in the breadth and nature of coverage of suicide.

Nor is this the only type of contagion. “Mass shootings are on the rise and so is media coverage of them,” writes Jennifer Johnston, PhD, of Western New Mexico University. Though that might seem like a chicken/egg scenario, Johnston and a coauthor studied a slew of such incidents, how those incidents were reported, existing literature on shootings, and FBI data. They concluded that “media contagion” is largely responsible for the sharp uptick in mass shootings.

Johnson is skeptical of the media’s motives, alleging that journalists bloviating about “the public’s right to know covers up a greedier agenda, to keep eyeballs glued to screens, since they know that frightening homicides are their No. 1 ratings and advertising boosters.” She notes that the shooters’ well-established quest for notoriety “skyrocketed since the mid-1990s in correspondence to the emergence of widespread 24-hour news coverage.” The result is a danse macabre between murderer and media. Which returns us to a very specific kind of killing—the George Floyd kind.

First, a few facts about racism. The General Social Survey (GSS) and other broad indices confirm that organic racism has been in steady decline since the 1970s. Police killings of young black men have dropped 70 percent during the past half-century. Eighteen unarmed black people were shot by police in 2020—not the “thousands” hypothesized by young black respondents in contemporaneous man-in-the-street interviews. (Yes, Floyd’s death was unusually grisly; but that goes to atypicality.)

Opposition to interracial marriage has all but fallen off the charts, from a high of 96 percent in 1958 to just six percent today. Redlining—the practice of steering black home-buyers to poorer neighborhoods—has decreased to the point where, today, the majority of people living in formerly redlined neighborhoods are not black. Even reports of more subjective measures of racism, such as slurs, were on a steady downswing through the early 2000s. In other words, since the media unapologetically abandoned even the pretense of objectivity in order to champion “justice” causes, it has become the primary driver of our feelings on race.

“[A]t a time when measures of racist attitudes and behavior have never been more positive, pessimism about racism and race relations has increased,” writes Eric Kaufmann in his ambitious study for the Manhattan Institute. That study was later distilled into a Newsweek op-ed titled, “The Media Is Creating a False Impression of Rising Racism.” Kaufmann and others argue that the insistent drumbeat of racialized media coverage has black Americans (and white allies) believing that abuse is far more common than it really is.

That drumbeat gets steadily louder. As Zach Goldberg pointed out in an essay for Tablet, the terms racist/racists/racism accounted for just 0.0027 percent and 0.0029 percent of all words in the New York Times and the Washington Post, respectively, in 2011. By 2019, those same terms would constitute 0.02 percent and just under 0.03 percent, respectively, of all words published in the Times and Post—an increase of between 700 percent and 1,000 percent.

Goldberg notes that leading publications have dramatically broadened the definition of racism while also painting a more polarized and hysterical portrait of American race relations. A lengthy feature in the New York Times Magazine explicitly alleged an American “caste system” and compared the US to Nazi Germany. A more recent Times story about a white female dog-walker who called the police on a black male bird-watcher reported that this obscure story was “rattling the nation.” (If you’re the “paper of record” and you publish a story under that rubric, the nation will dutifully rattle.)

By redefining everything as racism and/or sensationalizing anecdotal cases of racist behavior, latter-day journalism helps to realize its own false narratives, say Kaufmann and others, by needlessly inflaming racial tensions. Thus, a nation in which race relations were improving “lives down” to its own news coverage.

The cultural valence of such journalism is hard to miss. Eight in 10 black respondents to a 2020 Qualtrics survey believed that young black men are more likely to be shot to death by police than die in a traffic accident. The actual numbers aren’t even close: 7,494 black people died in traffic accidents in 2020, a 30-fold spread over the 243 black Americans (armed or unarmed) shot by police that year. And in a jaw-dropping poll analyzed by Skeptic, over 20 percent of those self-describing as “liberal” or “very liberal” believed that police killed 10,000 unarmed black people in 2019.

Such misapprehensions are frequently left unchallenged by large sections of the media. When the Floyd story broke and the media began running that grim cellphone video, in whole or in part, over and over again, very little time or attention was spent pointing out the statistical anomaly of such events or the lack of hard evidence supporting a vendetta against black people (see also here). On the contrary, the media insisted, “This is your America.” Viewers were treated to nonstop circular punditry: We know the Floyd case is rooted in racism because America is racist, ergo it should be added to the body of evidence affirming America’s racism. Even the normally temperate Van Jones made this argument.

Floyd was named in close to two million (1,880,507) news items in the two weeks following his murder. Over half of those reports linked his death to racism. Here again the “Tide effect” obtains: In recurring ads, we don’t just watch the same (fake) couple enjoying their freshly washed laundry over and over again—we infer a much larger message: People love Tide! In the Floyd coverage, we don’t just see cops assaulting the same black man over and over again, we infer the message that cops assault black America!

According to a widely cited literature review conducted at the University of South Florida, “When African Americans view footage of other Black people being killed by police, they are likely to see themselves or a close loved one in that person’s place, in an idea that social scientists refer to as ‘linked fate.’” It is like a death in the family. This effect is most pronounced after “high-profile police killings,” which, as with suicide, raises a question: Is the event itself the problem—or is the “high profile” a function of the multiplier effect supplied by media virality?

Even when journalism isn’t persuading black Americans that they’re destined to die in a police stop, it attacks their sense of emotional wellbeing. Health scholars posited a toll of 55 million additional days of mental distress over the base rate for black Americans in the aftermath of the Floyd blitz. Even before Floyd, a major 2018 Lancet study portrayed the impact of such killings as a disaster for black mental health. A smaller study of pregnant black women found that they see police violence in their kids’ futures: “I’m always expecting that phone call.” The study suggested that such fears could even lead to unfortunate health outcomes for black infants.

And that may not be the worst of it. Keenan Anderson and Tyre Nichols are two black men who died after encounters in which they voiced fears of ending up like Floyd. Anderson plaintively declared, “They’re trying to George Floyd me.” What role could such an ambient mindset have played in predisposing their decision to flee or fight? Though a California University at San Bernardino literature review, titled “Why Do They Resist?”, dates back to 2003, its assessment of the dynamics of combative police stops is germane. The encounters most likely to result in resisting arrest were not those connected to the most serious crimes but rather involved black offenders who felt disrespected by police or suspicious of their motives during lesser matters like traffic stops.

Writer Mike Muse confirms this sentiment in a column for Level. “Resisting is reflex,” he writes. “We know it deeply, because we know the stories of those who came before us: adrenaline threat supersedes rational thinking. Our strength is our only protection from a world of endless fear.” But what if that fear is unsubstantiated? “A media-generated narrative about systemic racism,” writes Kaufmann, “distorts people’s perceptions of reality and may damage African-Americans’ sense of control over their lives.” He notes that merely reading a passage from author Ta-Nehisi Coates has been found to erode black respondents’ sense of agency.

Killing us loudly with its song

The news is making us all miserable. This truism emerges in study after study. A survey of 4,675 Americans in the weeks following the Boston Marathon bombings revealed that people who engaged with more than six hours of media coverage per day were nine times more likely to experience symptoms of acute stress. Another study found that people who watched negative material showed an increase in both anxious and sad moods after only 14 minutes of watching TV news. Even when the information is important, the deleterious effect remains. The more frequently people sought information about COVID-19 across various media, the more likely they were to report emotional distress.

“It can be damaging to constantly be reading the news because constant exposure to negative information can impact our brain,” offers licensed social worker Annie Miller. She explains that difficult media material activates our fight-or-flight response, flooding the body with hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Such bio-responses can be as addictive as they are unhealthy. The perverse and self-perpetuating psychological tic known as “doomscrolling” refers to the act of obsessively reading bad news despite the onset of anxiety and depression.

Perhaps most tragically, journalism appears to be poisoning the minds of America’s youth, who already struggle enough with the effects of social media and influencer culture. “They may have just read about an animal on the verge of extinction or the latest update on the melting polar ice caps,” says family-practice psychologist Don Grant. Or the effect may be second-hand, as a result of hearing their parents bemoan the latest horror stories.

Journalism is a factor in the ultimate act of cynicism—the decision not to procreate. In a recent poll, nine percent of respondents cited “the state of the world” as the key reason for their disinclination to have children. Young couples have been conditioned to expect their kids to do less well financially, and to have a lower overall quality of life. They fear for the very future of the planet. Headlines like this one probably don’t help: “It’s a Terrifying Time to Have Kids in America.”

We can debate whether the declining birth rate is itself a good thing or a bad thing, but it matters that opting out of family life is at least partly a function of fiction. It matters that at least some of us are contemplating species suicide in response to today’s bottomless media cornucopia of murder, disease, disaster, depravity, disunity, and every possible “ism” or “phobia.” Psychologically, journalism has us buckling ourselves into that one plane that goes down, day after day after damn day.