Politics

Public Broadcaster, Private Celebrity

Lineker has embarrassed the BBC but the vexing problem of illegal immigration will still have to be addressed.

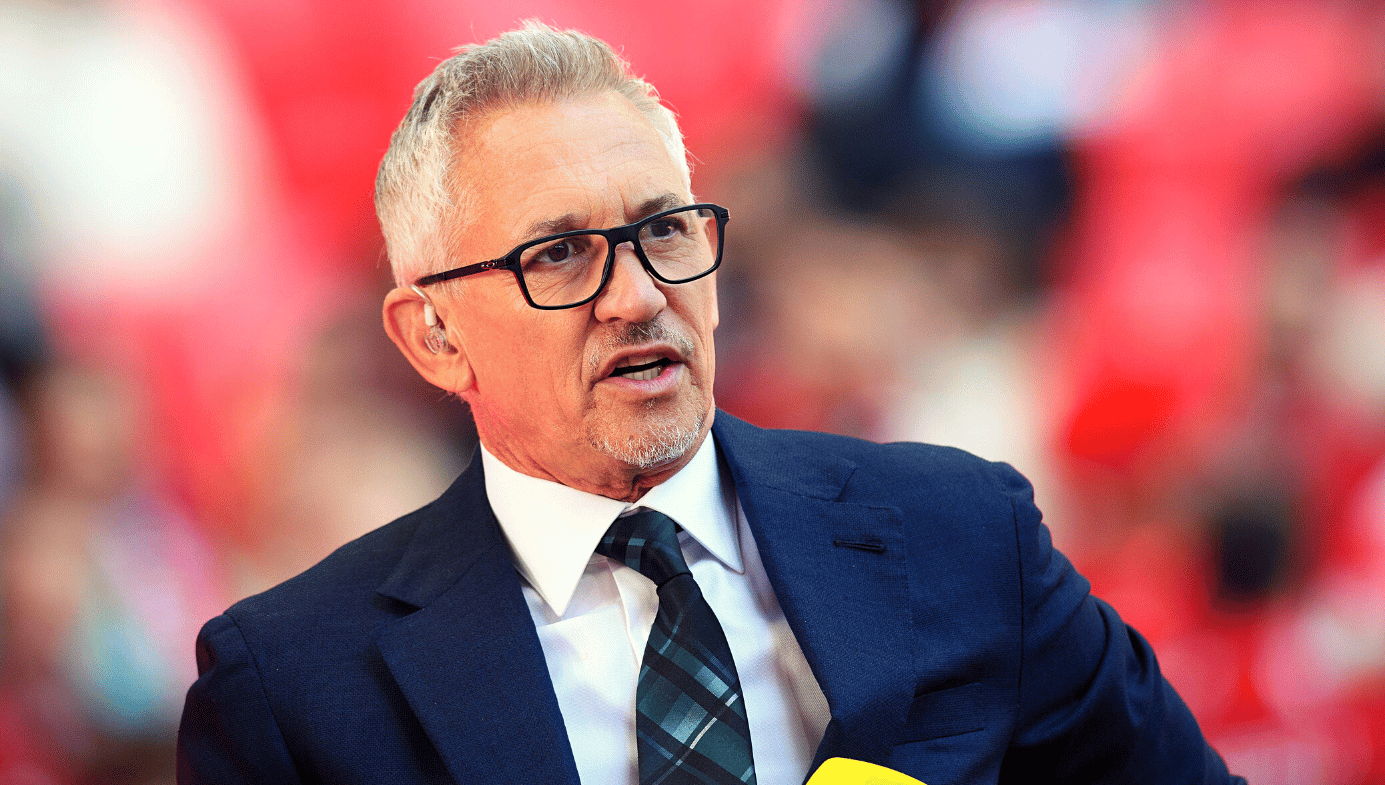

Two media systems clashed in the United Kingdom this past week. The universally recognised and much larger one, the British Broadcasting Corporation, was widely thought to have lost. Gary Lineker—who is paid between £1,350,000 and £1,355,000 to present Match of the Day on BBC1 (the BBC’s highest fee), appears in TV commercials, runs a media company called Goalhanger Films, and is highly popular with viewers—was widely thought to have won. If that turns out to be the case, it will be a bad result. But the outcome will only become clear in the long term, and winning goes far beyond the BBC and its chief sports presenter.

The BBC is a public broadcaster—indeed, the model for public broadcasters. Since the mid-1920s, it has provided news, current affairs, drama, entertainment, and education, funded by a state-backed licence fee. Gary Lineker oversees a private media empire and he is able to attract large audiences through mastery of the medium, charm, and—in his case—a stellar career for club and country as a professional footballer.

The clash arose from a tweet Lineker sent last week about the Conservative government’s new Illegal Immigration Bill, set out by Home Secretary Suella Braverman. The bill aims (not for the first time) to halt the flow of undocumented immigrants, many of whom reach the UK across the English Channel in small boats organised by people smugglers. In his tweet, Lineker described Braverman’s law as an “immeasurably cruel policy” and the language she used to defend it as “not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s.”

There is no huge influx. We take far fewer refugees than other major European countries. This is just an immeasurably cruel policy directed at the most vulnerable people in language that is not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s, and I’m out of order?

— Gary Lineker 💙💛 (@GaryLineker) March 7, 2023

Over 45,000 people came to the UK by boat in 2022, and on present trends, more than 80,000 can be expected this year. The numbers requiring deportation will therefore be huge. For immigrants seeking to enter the UK illegally, the proposed law will present a formidable barrier. Anyone found to have entered the country illegally will be either swiftly returned to their home country or sent to a third country with no opportunity to plead their case. This applies to everyone, including those who may find themselves in danger should they return, for example, to Afghanistan. The UK has an agreement to send illegal immigrants to Rwanda, but this has been challenged in the High Court, upheld, and is now in limbo pending further legal challenges. The law may, in any case, contravene the European Convention on Human Rights, which still covers the UK even after Brexit. Braverman herself, in remarks to Conservative MPs, admitted as much.

In response to Lineker’s tweet, the BBC’s director general, Tim Davie, decided to take the presenter off-air last Saturday. Lineker, Davie maintained, had breached BBC guidelines governing what employees can and cannot say in public, including on a personal Twitter account. After a weekend during which he received a deluge of criticism from Lineker’s co-presenters and supporters on social media and in the press, Davie appeared to change his story. He now explained that he had acted to buy some time to discuss past and possible future social-media outbursts, and that this had been a “proportionate action” and “the right thing” to do.

While these discussions continue, Match of the Day will be back in its accustomed slot, with Lineker in his accustomed chair. The row will not be tidied away, however. Conservative MPs have already started calling for Davie to resign, but he has so far refused to do so. The chairman of the BBC’s board, Richard Sharp, is also being asked to resign, partly because he did and said nothing during the row to defend the corporation’s political neutrality. Others believe him to be politically compromised because he helped then prime minister, Boris Johnson, secure an £800,000 loan before he was named as chairman. An inquiry has been opened into the affair (inquiries into government actions or inactions are now so frequent that they bump into each other in Westminster).

Was the BBC’s impartiality—and its political impartiality, in particular—seriously breached by Lineker? Or was Davie’s decision to suspend him another kind of breach—of the presenter’s right to speak and publish freely? In the present BBC guidelines (now under review), one clause seems to offer the director general support:

Where individuals identify themselves as being linked with the BBC, or are programme makers, editorial staff, reporters or presenters primarily associated with the BBC, their public expressions of opinion have the potential to compromise the BBC’s impartiality and to damage its reputation. This includes the use of social media and writing letters to the press. Opinions expressed on social media are put into the public domain, can be shared and are searchable.

But a further clause adds:

The risk [of damaging BBC impartiality] is greater where the public expressions of opinion overlap with the area of the individual’s work. The risk is lower where an individual is expressing views publicly on an unrelated area, for example, a sports or science presenter expressing views on politics or the arts.

In other words, a BBC presenter really should not use social media to make a political statement, especially an incendiary one invoking Nazi Germany, even if it is not directly related to his own output. As for the free speech, many hundreds of thousands of British citizens are forbidden from expressing their political beliefs in public. Civil servants are sworn to develop the political programme of the government of the day, whatever they think of it. The prohibition on commentary becomes implicitly stronger the more senior an official is—a permanent secretary of a ministry who sent a tweet censuring government legislation in the terms Lineker used would be unemployable for the rest of his life.

So, yes, Lineker breached the BBC’s guidelines on political impartiality, no matter how one reads them. And he did so by comparing Braverman’s language to that employed by Nazis (her husband is Jewish, but he may not have known that). The comparison, whatever one thinks of the new bill, was absurd, and like all such comparisons, it was an insult to Nazism’s victims. As one of Scotland’s best commentators, Iain Macwhirter, pointed out, Lineker was defended by other well-known and wealthy figures because they, like him, hold liberal/left views. Had he decided to defend a conservative position or policy, Macwhirter wrote, “I suspect that most of the commentators defending him now would have said he shouldn’t be using the BBC as a platform to promote socially regressive ideas and that the BBC should not be allowing this. Why should he used [sic] tax-payer’s money to promote a right wing cause? What gives him the right?”

A different but related point was made by the political scientist Matt Goodwin:

the government’s new policy, as I wrote last week, is far more popular than most people, especially the liberal progressives who congregate on Twitter and are far more likely to share their personal views on the platform, like to believe. If, like Gary Lineker, you strongly oppose the government’s promise to remove illegal migrants and asylum-seekers and prevent them from returning to Britain in the future then you do not represent a majority but just 16 per cent of the country.

Illegal immigration is unpopular more or less everywhere, but legal immigration is not. Many thousands of people may enter a country legally with a desire to stay and work and take part in public and civic life. This kind of controlled migration is not unpopular—especially not in the UK, where legal immigration remains high. But those who come to the UK illegally do so, in many cases, because they are fleeing war, hunger, and oppression—evils that are unlikely to disappear soon. And pressure on the rich countries will continue to increase, so long as they offer millions an opportunity to live better lives. This ought to be obvious.

We have a moral imperative to find an answer to this conundrum that also addresses our own security, threatened by ever more determined attempts to leave failing and turbulent states. We will have to consider humanitarian interventions once more, which seek to obtain agreement from the elites of failing states to undertake meaningful reforms. These will have to transform such states into nations that are able to inspire pride, provide stable and secure family living, and instil reasonable honesty in government and in the economy. This may sound like cloudy idealism, but as states fail—Haiti; Somalia; Pakistan—and neither oppression nor rampant corruption decline, what other response can we imagine besides international development? And how can we gather sufficient global commitment to support it?

This is a reply to a stupid tweet by a cocky celebrity. But so long as we content ourselves with merely approving (or, for that matter, disapproving) of Lineker’s trite dismissal of the government’s attempt to stem an unpopular tide, we miss a larger point. Feel-good, audience-pleasing, Nazi-likening commentaries drag us away from serious thought on this matter—something which, for all its faults, the BBC still sees as part of its public duty. So, short-term appearances notwithstanding, the BBC may win this match in the end. Victory in the matter of immigration—the reasons for it and the mountain to climb to really address it—will be a much harder battle to fight.