America’s Forgotten Crisis

A terrific new account of America’s social and political turmoil during the 1910s and ’20s provides some much-needed perspective on the problems afflicting the country today.

A review of American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild, 432 pages, Mariner Books (October 2022)

What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.

~Ecclesiastes 1:9

One of the rewards of reading history is the discovery that the present isn’t uniquely perilous or even unique. Amid the chaos and catastrophism of 2022, some historical perspective can provide a valuable reminder that humanity’s earlier rough patches were a lot worse than this one. I don’t just mean the world’s most infamous man-made disasters like the Second World War and the Holocaust, but also other less notorious periods that have been all but forgotten in the decades since.

We have become so used to hearing that Americans are more politically polarized now than at any time since the Civil War in 1861–65 that such a statement is now accepted as a truism. It might even be correct, but it hardly means that we’re doomed to repeat the Civil War or that we are facing our most serious internal crisis since then. Consider the late 1910s and early 1920s, a time when the United States was roiled by violent social unrest, apocalyptic paranoia, government censorship, turbocharged xenophobia, Stasi-like mass surveillance and repression, and racist lynchings and pogroms. One can only imagine how stressful and exhausting the era would have been with a 24-hour news cycle and social media hyping the latest real and imagined outrages.

And yet this convulsive era is lost to time and memory, as though it never happened. We “remember” the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Great Depression, and the political and cultural upheavals of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The last of these still exists within living memory and the earlier emergencies were more monumental and consequential. But the forgotten period, the one that is seldom invoked or even named, was nonetheless more dangerous and unhinged than the one we’re living through now.

Historian Adam Hochschild brings this period to life in his terrific new book American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, “a story of how a war supposedly fought to make the world safe for democracy became the excuse for a war against democracy at home.” Like all the best history books, American Midnight reads like a novel with three-dimensional characters, from President Woodrow Wilson and Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs and Russian-born anarchist Emma Goldman.

Hochschild begins with President Wilson, a Democrat and a progressive. It’s important to note here that both parties back then had progressive and conservative wings and that both have since undergone ideological realignments, so the labels don’t mean the same things now that they did then. Nevertheless, Woodrow Wilson remains one of the most monstrous presidents in our country’s history. University students today insist that he was a racist—which he certainly was—but his faults hardly end there. During his tenure, the United States assumed more characteristics of authoritarianism than at any time before or since.

Wilson’s presidential campaign pledged to keep the country out of the meat-grinding war across the Atlantic, and he kept that promise for nearly three years until Congress declared war on Germany in April 1917. But American Midnight isn’t about the First World War. It’s about what happened at home during and after it. The declaration of war in the House of Representatives passed by 373 votes to 50, and while most Americans approved of the decision, there were noisy pockets of dissent, as there are whenever democracies fight wars. Wilson feared that even the mildest bleats of complaint would undermine the morale necessary to sustaining the war effort. The upshot was the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which had almost nothing to do with actual espionage. Instead, it declared any kind of anti-war activity to be criminal, and defined “opposition” in ways that few modern critics of pacifists and isolationists would even recognize.

Anyone who “shall willfully make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation of the military or naval forces of the United States” was subject to arrest. It would be a mistake to assume that the Wilson administration was only going after the purveyors of what we now call “fake news,” or to get hung up on the words “with intent to interfere.” Ordinary people were rounded up and prosecuted who had no intention of interfering with anyone or anything, and those convicted faced up to 20 years in prison—twice as long as the sentence Vladimir Putin metes out to his Russian subjects for similar offenses today.

A Texas man was jailed for saying, “I wish Wilson was in hell.” Andreas Latzko’s novel Men in War was banned for describing the war as a “wholesale cripple-and-corpse factory.” Police officers arrested playwright Eugene O’Neill at gunpoint on Cape Cod because somebody saw sunlight reflecting off his typewriter and thought he was sending signals to German ships. Filmmaker Robert Goldstein was arrested for co-writing and producing a silent film called The Spirit of ’76 about the American Revolution. Regardless of what happened in 1776, the presiding judge said, “we are engaged in a war in which Great Britain is an ally of the United States,” and this was not the time for “sowing dissension among our people” or “creating animosity … between us and our allies.” Goldstein was handed 10 years in prison.

It became a federal offense to send “seditious” newspapers and magazines through the mail, which was the only way anyone could subscribe to them in the days before the Internet. Masses magazine, for instance, was deemed “unmailable” after it published a political cartoon that showed the Liberty Bell crumbling. A pamphlet titled “Why Freedom Matters” was banned not for criticizing the war but for criticizing censorship. At least the author of the pamphlet knew why. “Sometimes,” Hochschild writes, “as if anticipating the protagonist of Kafka’s The Trial, a journalist could not even learn what he or she was accused of.” Newspapers and magazines in foreign languages were likewise banned whether they criticized the government or not. Who knew what kind of diabolical speech might appear in a paper that censors couldn’t read?

This censorship was accompanied by a repressive clampdown that’s hard to even imagine today. President Wilson’s special emissary, a former senator named Elihu Root, said, “There are men walking about the streets of this city tonight who ought to be taken out at sunrise tomorrow and shot for treason. There are some newspapers published in this city every day the editors of which deserve conviction and execution.” Vice President Thomas R. Marshall said he wanted Congress “to take away the citizenship of every disloyal American—every American who is not heartily in support of his Government in its crisis … I would annul the citizenship of every such individual and confiscate his property.”

The Department of Justice authorized former advertising executive Albert Briggs to deputize civilian vigilantes into the American Protective League (APL), which had 1,200 chapters and roughly 250,000 members. They tapped phones and placed bugs in the homes of those they surveilled. They raided houses and seized documents. They rode trains and listened for “disloyal” speech. The Seattle branch alone investigated more than 10,000 people and arrested more than a thousand, 499 of whom were charged with “seditious utterances.” One official described a Midwestern chapter of the APL as “the Ku Klux Klan of the prairies.” He meant it as a compliment. The Bureau of Investigation (which later became the Federal Bureau of Investigation) likewise sent spies into legal organizations.

In Chicago, 10,000 APL agents went on a full-bore repression spree. “At movie theaters, vaudeville shows, and a Cubs doubleheader,” Hochschild writes, “the raiders made everyone file out of designated exits, where each draft-age man had to show his card. Badge-wearing vigilantes checked every arriving train or steamboat, and combed parks, bars, restaurants, elevated train stations, and nightclubs. They stopped cars to question drivers and passengers and even appeared at the beaches in bathing suits, wading into Lake Michigan to interrogate suspects.”

Even after the war ended, state repression and censorship continued unabated. A few senators introduced a bill to put a stop to it but got nowhere. Its failure, remarked progressive Republican Robert La Follette, “ought to make the framers of the Constitution open their eyes in their coffins.”

History everywhere alternates between periods of calm punctuated by periods of turmoil. No country can remain at a furious boil forever, but the quiet interludes have expiration dates of their own. And the late 1910s and early 1920s were a tumultuous time. Inflation soared more than 40 percent between 1917 and 1920 alone. Waves of immigrants were arriving from Europe bringing unfamiliar languages and customs. The social order among native-born Americans was also in flux as women prepared to win the right to vote for the first time.

With war raging against Germany, anyone speaking German on American streets risked a beating. While this sort of thing is common everywhere in the world during wartime, fulmination against immigrants in general, German or otherwise, reached a fever pitch, and some American states banned the public use of all foreign languages.

Most immigrants at that time were arriving from Italy, Eastern Europe, and the Russian Empire. They were predominately Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox. Today, most of us would lump them together as “white,” but back then the recent arrivals were reviled the way refugees and asylum seekers from Latin America are despised in certain circles today. Representative Albert Johnson of Washington state decried what he called “wops,” “bohunks,” “coolies,” and “Oriental off-scourings” in the chambers of Congress. Wilson himself lamented that “the countries of the south of Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population.”

Meanwhile, social strife and political violence became nearly as ubiquitous as the so-called Spanish flu during the 1918 pandemic, which killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide without Wilson bothering even to mention it. Socialists, anarchists, and right-wing vigilantes beat each other in the streets with clubs. In Boston, war opponents and union members clashed with right-wingers in a melee involving 20,000 people. (The Trump-era Thunderdome showdowns in downtown Portland between left-wing and right-wing hooligans only numbered a couple of hundred.) Anarchists murdered dozens in bomb blasts at offices and private homes, often accompanied by leaflets saying, “You jailed us, you clubbed us, you deported us, you murdered us.”

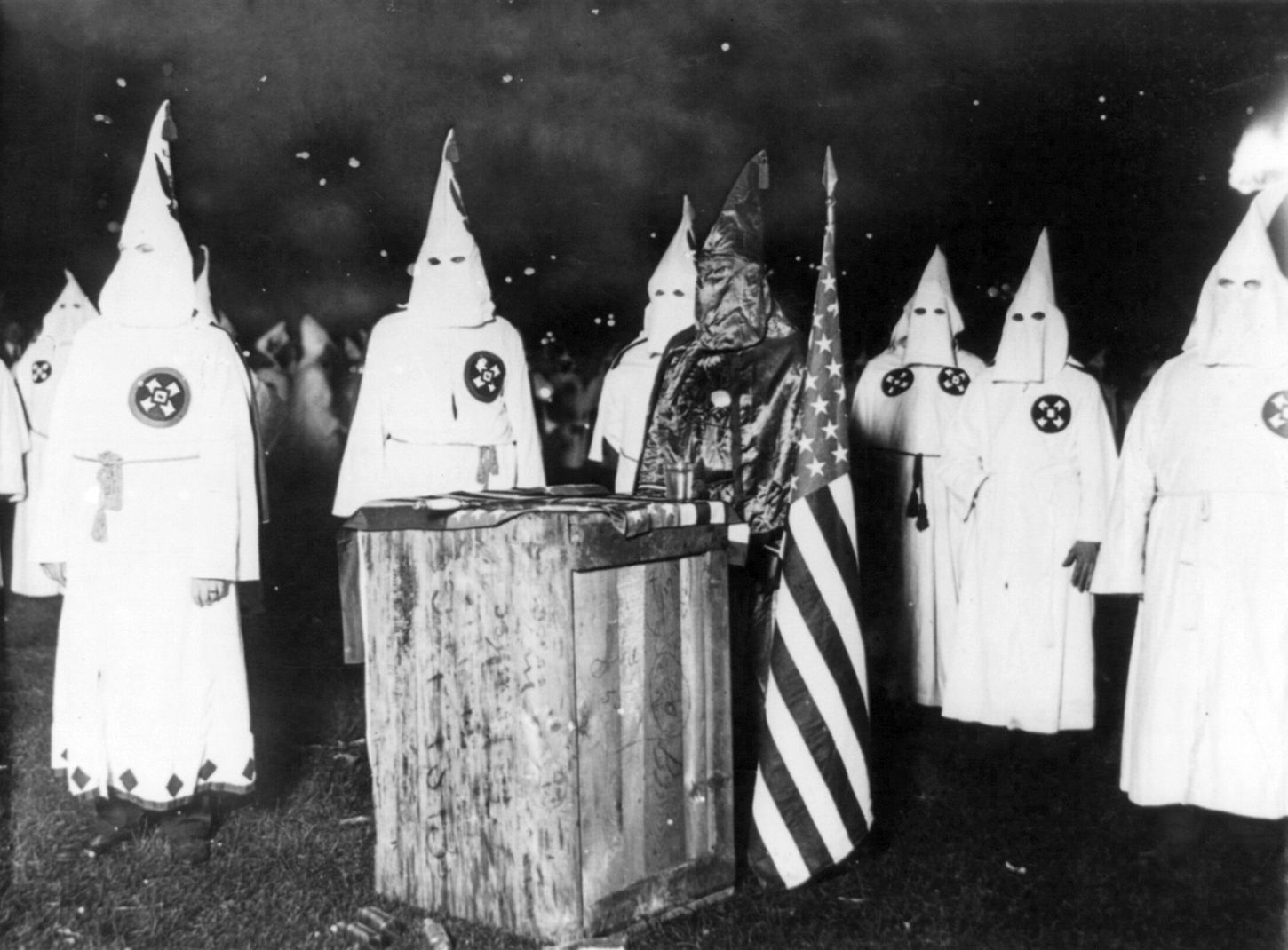

The worst violence was racial. The Ku Klux Klan revived itself from near-extinction in 1915, and burst from its former confines in the South into every state in the union. Their hooded horsemen were the heroes of D.W. Griffith’s groundbreaking but unambiguously racist 1915 propaganda epic, The Birth of a Nation. President Wilson screened the film in the White House and remarked, “It’s like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” In Chicago, white gangs drove through black neighborhoods, firing at random. They yanked people out of restaurants and shops and beat them in the streets.

Black citizens fled north from the violently segregationist South for perfectly obvious reasons, but the Democratic Party, deploying an earlier iteration of the “Great Replacement Theory,” accused the Republicans of importing black people to dilute the urban Democratic vote. Racist and paranoid talk led inexorably to violent, racist action. In East St. Louis, Illinois, an enraged white mob torched more than a dozen blocks of a black neighborhood where recent southern arrivals had chosen to settle, and they threatened to shoot anyone who tried to escape. They destroyed 245 buildings, killed up to 150 people, and even threw a child into the fire. Oscar Leonard at the Jewish Educational and Charitable Association of St. Louis rightly called it a pogrom. Wilson had no more to say about this than he did about the pandemic. Why would he? The man was a ferocious racist, not only by the standards of our era but by his own. As a young man, he wrote in his diary, “Universal suffrage is at the foundation of every evil in this country.”

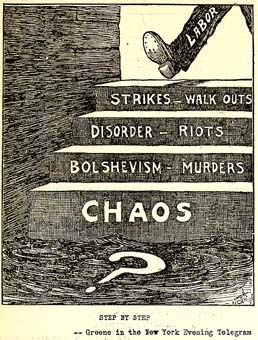

Most Americans may have been relatively indifferent to racial violence, but labor violence also loomed large. During general strikes, workers attacked strikebreakers with bricks and knives. Ominous talk of revolution and sabotage became even more frightening after the 1917 revolution in Russia and the civil war there that followed it. The Industrial Workers of the World (colloquially known as the Wobblies) were everybody’s favorite boogeyman—their newspapers occasionally advocated “industrial sabotage,” but they never explicitly stated what that meant and no one in the IWW was ever actually convicted of that crime. One of the first general strikes took place in Seattle, and the entire city fell silent as if bracing for war. Many fled to hotels in Portland, 175 miles to the south. The mayor accused labor of hoping “to duplicate the anarchy of Russia” and swore in an additional 3,000 police officers. Today, Seattle only has a total of 940 police officers even though the city is more than twice the size it was then.

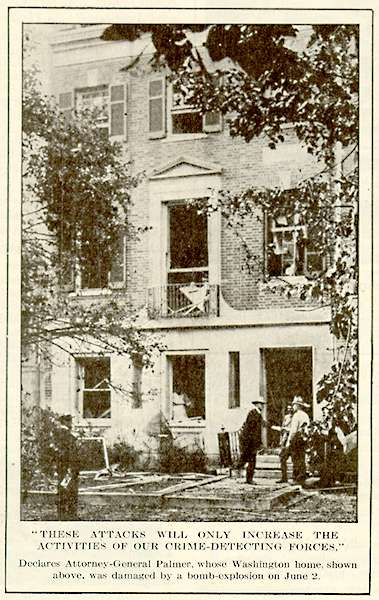

Anarchists may have been smaller in number than socialists, but they were more violent. One of them planted a bomb on Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s porch, but blew himself up when he tripped and destroyed the front of the house. (Palmer survived.) Most evidence pointed toward a small band of Italian anarchists called the Galleanisti. Their leader, Luigi Galleani, completely failed to understand how Americans feel about this sort of thing and believed that left-wing terrorism would spark a left-wing revolution. But no one was ever captured and prosecuted for the attack, and Palmer publicly blamed it on the Wobblies, who were vastly more numerous and easier to round up.

With the specter of Russia looming so large, socialism terrified Americans more than anarchism did. “Over the next few years,” Hochschild writes, “people would blame Bolshevism for everything from strikes to anti-lynching protests to loosening sexual mores to untrimmed beards.” When the Boston police went on strike, the Wall Street Journal hysterically announced that “Lenin and Trotsky are on their way.” A Los Angeles Times editorial asked, “Has Bolshevik Russia presented any more alarming spectacle than this?” The cops did not mount a communist putsch. They just wanted pay raises, shorter shifts, and the same right to unionize that local firefighters enjoyed. Instead, the strike ushered in a more prosaic kind of disaster: with so few police officers on duty, looters smashed their way into stores, and criminals from other cities took trains to Boston to grab some loot of their own. Wilson lamented that Boston was “at the mercy of an army of thugs” and described the episode as “a crime against civilization.”

In November 1919 and January 1920, with the Red Scare nearing its apogee, Palmer’s men rounded up thousands of suspected socialists, anarchists, and communists and threw them into makeshift prisons, where they awaited deportation. He singled out the Wobblies, of course, but also the Union of Russian Workers, often on the flimsiest evidence. In Detroit, for instance, agents interrogated every theatergoer watching a Russian-language play. No court ever convicted a single member of violence.

Palmer’s men arrested and interrogated around 10,000 people that winter, many of whom were not communists and were shocked to discover that anyone thought they were. Palmer promised to deport tens of thousands more. He warned that a mass communist uprising would unleash hell in the United States on the upcoming May Day, and much of the country was consumed with anxiety. “Headlines about Red-hunters and bombings sold papers when the press could no longer offer readers suspenseful daily reports from Europe’s battlefields,” Hochschild writes.

The Army put together what it called War Plan White to put down the supposedly imminent insurrection, and it singled out Jews, Eastern Europeans, and Russians as “undoubtedly the most dangerous element of our population.” The US Army deployed tanks in Cleveland, set up machine-gun nests in Omaha, and drafted plans to place the entire country under martial law. Washington, DC looked like a city preparing for a siege. New York Chief of Military Intelligence John B. Trevor drew up “Plans for the Protection of New York in Case of Local Disturbances.” The Army would need 10,000 soldiers to protect Manhattan and another 4,000 to defend Brooklyn. He requested a battalion of machine gunners in “the congested district chiefly inhabited by Russian Jews,” the Lower East Side.

But May Day came and went, and nothing happened. There was no insurrection. Even the heaving street violence of prior years failed to materialize. It was as if Palmer were the leader of a doomsday cult predicting the end of the world on a specific date only to realize that the date in question was (surprisingly!) no different from any other date on the calendar. It’s obvious a hundred years later that the United States was not on the verge of a communist revolution, but plenty of Americans believed it at the time after they heard that the Bolsheviks had overthrown the Russian Tsar and were now busy establishing a totalitarian state. “That this ruthless, relatively small party had seized power in such a vast country reignited an ancient American fear of secret conspiracies,” Hochschild writes, “something always stronger in unsettled times, when people fear that their own positions in life are threatened or eroding and need someone to blame.”

“In these times of hysteria,” Judge George W. Anderson said from the bench, “I wonder no witches have been hung,” and he set the prisoners Palmer had rounded up free. “In the end,” Hochschild writes, Palmer “proved as blind as many would-be revolutionaries to the fact that most Americans have seldom dreamed of an armed left-wing revolution.”

There’s no telling when the politically ludicrous era we’re living through now will finally exhaust itself, but it’s likely to end in the same way and for the same reasons that similar eras before it did: a critical mass of people simply decide that they have had enough and demand that it stop.

The Democratic and Republican primary elections that year marked a turning point, as did the general election that followed. Palmer ran for the Democratic nomination on a Red Scare platform (though that’s obviously not what he called it), singling out not only would-be insurrectionists but also, as he put it, “hysterical neurasthenic women who abound in communism.” It’s worth pointing out here that women had finally won the right to vote the previous year, thanks in part to Wilson, one of the things he got right during a break from his general monstrousness. Palmer’s ideological counterpart in the Republican Party was Edward R. Wood from Pennsylvania, a man so utterly forgotten that he doesn’t even show up on the first several pages of Internet search results. Both Palmer and Wood campaigned on the promise of mass deportations.

After thoroughly alienating the labor wing of the Democratic Party with his demagogy, Palmer lost the primary to the dull yet refreshingly reasonable Ohio Governor James M. Cox. Wood fared no better in the Republican primary. “Republican leaders,” Hochschild writes, “began to realize that the public no longer wanted a man on horseback to come to the country’s rescue,” and Wood lost to the more genial (but as it later turned out, corrupt) conservative Senator Warren Harding. Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Walter Lippmann dismissed Palmer and Wood as people consumed with “hatreds and violence … turned against all kinds of imaginary enemies—the enemy within, the enemy to the south, the enemy at Moscow, the Negro, the immigrant, the labor union.”

In 1920, Harding won in a landslide with more than 60 percent of the vote on a simple campaign promise: Back to normalcy.