Science / Tech

‘The Dawn of Everything’ and the Politics of Human Prehistory

David Graeber and David Wengrow’s tendentious assault on the Enlightenment and its modern defenders is a bust.

In 1885, Thomas Henry Huxley delivered a speech in which he famously declared that science “commits suicide the moment it adopts a creed.” The occasion was the completion of a statue of Charles Darwin for the British Museum, yet the man known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” felt obliged to emphasize that the monument should in no way be taken as an official sanction of Darwin’s ideas, because “science does not recognize such sanctions.” In science, the status of any idea is contingent upon the strength of the evidence supporting it, and must therefore be treated as provisional as data accumulates and our understanding deepens. Huxley intended his aphorism as a reminder that no belief, whether personal, political, religious, or even scientific, should be immune to questioning and revision.

But while many scientists continue to uphold the strict separation between scientific research and political advocacy, a growing number now argue that the convention of barring creeds from science is quaint—even reactionary. This trend is especially pronounced in the social sciences. As Allison Mickel and Kyle Olson write in a 2021 op-ed for Sapiens titled “Archaeologists Should Be Activists Too”:

There are still some who argue that scientists maintain their authority only when they remain objective, separate from current political concerns. Many academics have decried this view for decades, demonstrating that fully objective science has always been more of a myth than a reality. Science has always been shaped by the contemporary concerns of the time and place in which research occurs.

The suggestion here is that since researchers can never thoroughly eliminate politics from their work, they may as well ensure they are incorporating the correct politics into their foundational assumptions. We might call this the argument from inevitability. The “correct” politics are taken by most activists to consist of whatever is most beneficial to marginalized peoples—which usually means uncritically accepting those peoples’ own views or, if those views are inaccessible, choosing whatever narrative paints them in the most favorable light.

While this reasoning strikes many as both convincing and morally commendable, it is severely flawed. For instance, the inevitability of political concerns coloring our research does not justify abandoning efforts at reducing their impact. Pathogenic microbes will inevitably survive any effort at sanitizing an operating theater. That hardly means that surgeons should perform procedures in gas station bathrooms. Those whose goal is to arrive at the clearest and most comprehensive understanding of reality must strive to minimize the influence of prejudices arising from nonscientific beliefs and agendas as much as possible—even if eradicating them completely is beyond anyone’s capability. And, while it may seem admirable, even heroic, to err on the side of protecting those who may not be able to protect themselves, defaulting to the presumed victim’s truth comes with obvious drawbacks—the most important of which is that the presumed victim’s truth may not be true.

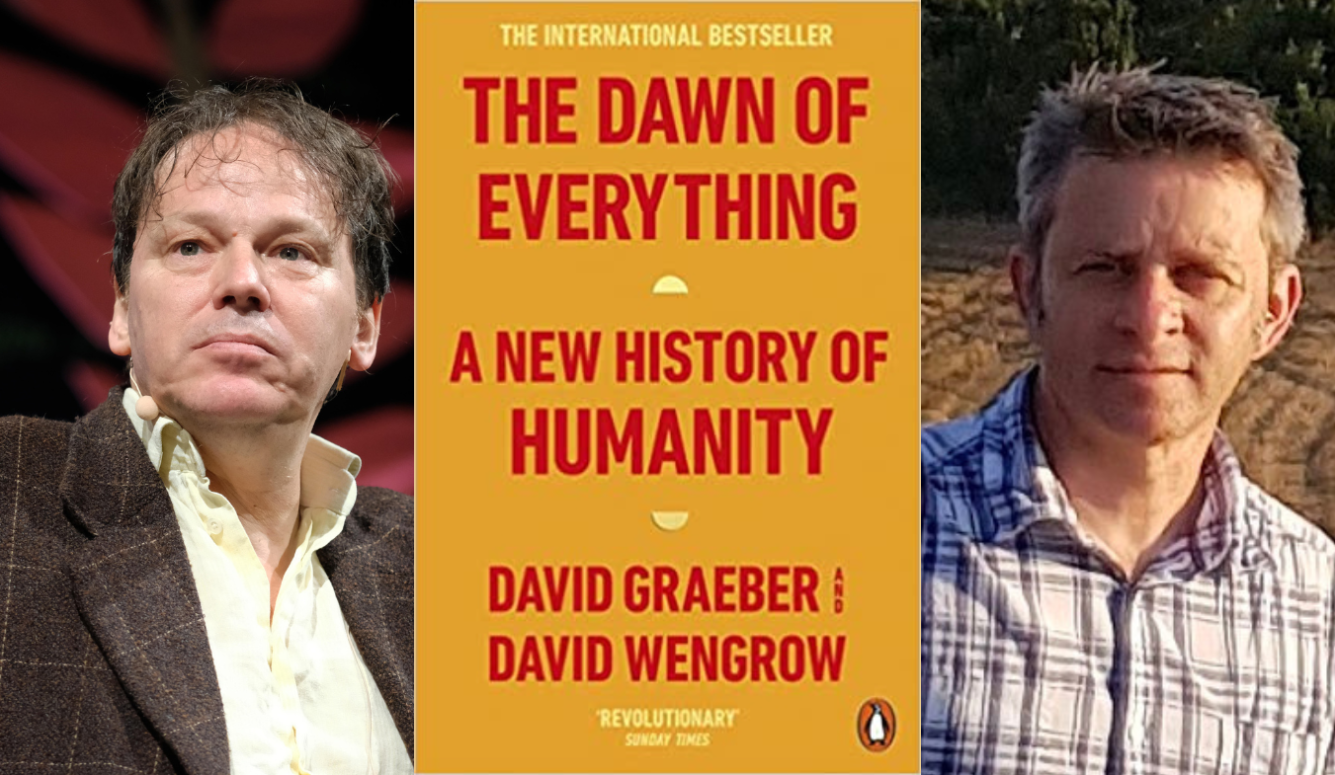

The late anthropologist and anarchist David Graeber presents a case study in what happens when one allows creeds and political interests to creep into science. For decades, Graeber participated in leftist and radical movements, and he was one of the original planners—an “anti-leader”—for the Occupy Wall Street protest. In January 2017, he tweeted: “does anyone know any handy rebuttals to the neoliberal/conservative numbers on social progress over the last 30 years?” In the thread that followed, Graeber elaborated:

again & again i see these guys trundling out #s that absolute poverty, illiteracy, child malnutrition, child labor, have sharply declined … that life expectancy & education levels have gone way up, worldwide, thus showing the age of structural adjustment etc was a good thing. It strikes me as highly unlikely these numbers are right … It’s clear this is all put together by right-wing think tanks. Yet where’s the other sides numbers? I’ve found no clear rebuttals.

Graeber responded to charges of motivated reasoning in the comments by insisting that he was merely demonstrating a scientist’s proper skepticism by looking for counter-evidence. What he failed to understand was that it was not the question itself that revealed his bias. It was that he characterized the data he was inquiring into as “neoliberal/conservative,” assuming without evidence they were “put together by right-wing think tanks.” Rather than treating the data as a possible window onto the nature of our civilization, he saw the numbers as points on a scoreboard for the opposing team, which he assumed could only have been counted because of partisan refereeing.

Graeber died in 2020, but his challenge to the narrative of social progress survives in his posthumously published book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, which he co-wrote with the archeologist David Wengrow. Their main thesis is that the traditional story of how human societies evolve from egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers to larger, more sedentary tribes to more hierarchical chiefdoms to highly stratified states governed by authoritarian rulers is wrong and should be overturned. This narrative, they argue, can be traced back to either Jean-Jacques Rousseau (if you believe that hunter-gatherers were peaceful and freedom-loving) or to Thomas Hobbes (if you believe they were miserable and warlike).

“Our objections can be classified into three broad categories,” they write in the first chapter, but only one of these objections is scientific: “these two alternatives,” the authors claim, “simply aren’t true.” The next two bullets complain that the conventional stories “have dire political implications,” and “make the past needlessly dull.” Graeber and Wengrow are troubled that ascendent social evolutionary theories treat hunter-gatherers as either savages or “innocent children of nature,” instead of crediting them with formulating lofty ideas about freedom and recognizing their ability to experiment with various social arrangements.

Unfortunately, the thinking Graeber and Wengrow outline at the beginning of each of their book’s sections usually comes with few if any citations, and when they do reference other work, they frequently misrepresent it. As the authors poke holes in their own tendentious generalizations about the scholarship in their fields, the reader may feel they’ve been buttonholed by a man at a bar boasting about how he bested impossibly dense adversaries in battles of wit. Indeed, the main problem with The Dawn of Everything is that it’s really just a long rant against a straw man—the view that societies progress inevitably and rigidly through a series of stereotyped stages. And it soon becomes clear that Graeber and Wengrow’s true beef is with the idea that large societies require some form of government domination, an issue that is, of course, close to the heart of any anarchist.

For Graeber and Wengrow, the study of human prehistory is dominated by researchers who assume that societies everywhere will inevitably progress through identical stages. Driven by the same key technological developments, they will arrive at some kind of modern state, characterized by heavy-handed, top-down control of the masses by the wealthy and powerful few. Late in the book, they admit that “almost nobody today subscribes to this framework in its entirety,” but add that:

if our fields have moved on, they have done so, it seems, without putting an alternative vision in place, the result being that almost anyone who is not an archaeologist or anthropologist tends to fall back on the older scheme when they set out to think or write about world history on a large canvas.

But to create the illusion that they are taking on the prevailing view, which they insist is disproportionately influenced by non-specialists, Graeber and Wengrow are forced to conflate modern scholarship with ideas from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. This is because modern scholars—both in and out of the field of anthropology—know better than to posit invariant rules about human behavior and society. Instead, they look for trends and correlations, as in the observation that hunter-gatherers tend to live in small-scale societies that tend to be egalitarian.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm, for instance, has penned some of the most widely cited books on hunter-gatherer egalitarianism. In the introduction to his book Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, Boehm writes, “I make the major assumption that humans were egalitarian for thousands of generations before hierarchical societies began to appear.” Graeber and Wengrow fault him for claiming “we were strictly ‘egalitarian for thousands of generations’,” though Boehm never used the word “strictly,” and his theory clearly allows for exceptions. “So,” Graeber and Wengrow continue, “according to Boehm, for about 200,000 years political animals all chose to live the same way.” They go on to complain of his “odd insistence that for many tens of thousands of years, nothing happened.” But Boehm insists on nothing of the sort. He writes:

When upstarts try to make inroads against an egalitarian social order, they will be quickly recognized and, in many cases, quickly curbed on a preemptive basis. One reason for this sensitivity is that the oral tradition of a band (which included knowledge from adjacent bands) will preserve stories about serious domination episodes.

If there were “domination episodes,” then something happened. If that is not clear enough, Boehm later writes that “a hunting and gathering way of life in itself does not guarantee a decisively egalitarian political orientation.” Graeber and Wengrow’s misrepresentation is especially frustrating because the implications of recent discoveries of hunter-gatherer earthworks and monumental building are important to theories like Boehm’s, but the authors are uncharitable to his ideas, preventing what could have been an edifying disagreement. “Blinded by the ‘just so’ story of how human societies evolved,” they write of their colleagues, “they can’t even see half of what’s now before their eyes.”

The two scholars whose works suffer the most scathing attacks in The Dawn of Everything are Jared Diamond and Steven Pinker. Diamond and Pinker also rely on the traditional sequence of cultural evolutionism in their works, but they both use Elman Service’s terms “band,” “tribe,” “chiefdom,” and “state” as descriptive categories, not as an explanatory theory of clockwork progression. Graeber and Wengrow nonetheless claim that Diamond’s theory is that farming destroyed hunter-gatherer egalitarianism. “For Diamond,” they write:

as for Rousseau some centuries earlier, what put an end to that equality—everywhere and forever—was the invention of agriculture, and the higher population levels it sustained. Agriculture brought about a transition from “bands” to “tribes.” Accumulation of food surplus fed population growth, leading some “tribes” to develop into ranked societies known as “chiefdoms.”

Did Diamond really argue that agriculture caused a series of transitions to more complex societies “everywhere and forever”? In the section of his book The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? that Graeber and Wengrow cite, Diamond writes:

The higher populations of tribes than of bands require more food to support more people in a small area, and so tribes usually are farmers or herders or both, but a few are hunter-gatherers living in especially productive environments (such as Japan’s Ainu people and North America’s Pacific Northwest Indians).

So, rather than asserting that agriculture sets off an inevitable march toward despotism, Diamond writes of trends and correlations, leaving unanswered the question of which direction the causal arrow points. He makes this focus on trends explicit very near some of the text that Graeber and Wengrow quote:

While every human society is unique, there are also cross-cultural patterns that permit some generalizations. In particular, there are correlated trends in at least four aspects of societies: population size, subsistence, political centralization, and social stratification.

Diamond’s emphasis on correlations, and on the importance of keeping exceptions in mind, is part of a page-and-a-half discussion of the advantages and drawbacks of using the traditional classification scheme.

Of course, disproving a categorical statement is far easier than refuting an argument about relative frequencies, so it is easy to understand the temptation. All Graeber and Wengrow need to torch their straw man version of Diamond’s ideas is to provide a counterexample or two, which is what they attempt to do in the following chapters. To get the real and inconveniently complicated story of what factors contribute to the increasing scale and complexity of a society, one would need to go beyond searching for examples or counterexamples for a given narrative.

The “dire political implications” of believing that agriculture leads to complexity and domination clearly affect the conclusions reached by Graeber and Wengrow, and the line separating their science from their politics only gets blurrier from here. Summarizing their case that the old evolutionary theories “simply aren’t true,” they write:

To give just a sense of how different the emerging picture is: it is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory. Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers, ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators.

Before examining the political motivations behind these assertions, we should first ask if anyone takes the position that agriculture and private property mark “an irreversible step toward inequality.” Diamond certainly doesn’t: “Remember again: the developments from bands to states were neither ubiquitous, nor irreversible, nor linear,” he writes early in The World Until Yesterday. Diamond even uses some of the same language as Graeber and Wengrow, writing, “Traditional societies in effect represent thousands of natural experiments in how to construct a human society.” But what is it about the transition from egalitarian bands to larger ranked societies that Graeber and Wengrow find so objectionable? After all, the first complex societies must have emerged from simpler ones, however wide the range of local factors may have been.

The story of agriculture leading to beliefs about private property leading to inequality harks back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, to whom the notion of the virtuous “noble savage” is popularly attributed (though this is an oversimplification of his views). The narrative that is routinely pitted against Rousseau’s is commonly attributed to Thomas Hobbes, who characterized life in a state of nature as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Diamond serves as a modern mouthpiece for Rousseau throughout The Dawn of Everything, though this requires a serious distortion of his work. Meanwhile, “We can take Pinker as our quintessential modern Hobbesian,” Graeber and Wengrow write. For them, though, the two sides of the debate about primordial societies are far less different than most scholars assume. Whether it is the advent of agriculture knocking over the first domino that ultimately ensures domination of the many by the few, or the surly temperament and straitened circumstances of the average hunter-gatherer necessitating the intervention of a government Leviathan to prevent melees, the outcome is the same. Hierarchy is rendered both necessary and inevitable. And that, it turns out, is the worst of the “dire political implications” of the traditional evolutionary sequence.

For Graeber and Wengrow, accepting the traditional formulation that larger scale tends to coincide with more concentrated power means “the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces.” This profound antipathy toward inequality and concentrated political power gels nicely with the strong anti-Western bias prevalent across academia, which is especially pronounced in the humanities and the social sciences.

Steven Pinker directly challenged this bias in 2011 when he published The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, a book that provoked the ire of many academics. Pinker argued that modern Westerners live in unprecedented peace and that violent death was once astonishingly common.

Graeber and Wengrow begin their criticism by pointing out that Pinker overlays his theories about declining violence on the outdated understanding of societal evolution they are working to supplant. Then they get personal:

Since, like Hobbes, Pinker is concerned with the origins of the state, his key point of transition is not the rise of farming but the emergence of cities. “Archeologists,” he writes, “tell us that humans lived in a state of anarchy until the emergence of civilization some five thousand years ago, when sedentary farmers first coalesced into cities and states and developed the first governments.” What follows is, to put it bluntly, a modern psychologist making it up as he goes along. You might hope that a passionate advocate of science would approach the topic scientifically, through a broad appraisal of the evidence—but this is precisely the approach to human prehistory that Pinker seems to find uninteresting. Instead he relies on anecdotes, images and individual sensational discoveries, like the headline-making find, in 1991, of “Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman.”

However, the referenced pages in Better Angels make it clear that Graeber and Wengrow are the ones making things up. The book is chock-full of statistics from scientific sources. Facing one of the two pages that mention Ötzi is a bar graph based on multiple scientific references comparing estimated rates of violence across different types of society. Furthermore, Pinker is not “concerned with the origins of the state” at all; he is interested in different rates of violence between states and other forms of society.

Tellingly, Graeber and Wengrow give the clearest expression of their contempt for Pinker in an endnote to a line criticizing his endorsement of Hobbes’s theories about the causes of violence. Is Pinker’s verdict on Hobbes’ ideas true? “As we’ll see,” Graeber and Wengrow write, “it’s not even close.” Here, they direct us to the following note:

If a trace of impatience can be detected in our presentation, the reason is this: so many contemporary authors seem to enjoy imagining themselves as modern-day counterparts to the great social philosophers of the Enlightenment, men like Hobbes and Rousseau, playing out the same grand dialogue but with a more accurate cast of characters. That dialogue in turn is drawn from the empirical findings of social scientists, including archaeologists and anthropologists like ourselves. Yet in fact the quality of their empirical generalizations is hardly better; in some ways it’s probably worse. At some point, you have to take the toys back from the children.

In other words, they are outraged that Pinker, a psychologist specializing in language and cognition, has had the audacity to discuss prehistoric societies and their implications for the modern world. Though they promise a decisive debunking to come—“As we’ll see”—what follows has little if any bearing on Pinker’s thesis.

Before considering which of Hobbes’s ideas Pinker endorsed, we should note that it is not Pinker who attempts to don Hobbes’s mantle. It is Graeber and Wengrow who try to smother him with it, just as they do Diamond by lumping him together with Rousseau. They insist that if we did a reappraisal of Pinker’s argument, minus the cherry-picking, “we would have to reach the exact opposite conclusion to Hobbes (and Pinker),” by which they mean, “our species is a nurturing and care-giving species, and there was simply no need for life to be nasty, brutish or short.” While it is true that Pinker credits Hobbes’s insights about the causes of violence, he also goes on to write:

But from his armchair in 17th-century England, Hobbes could not help but get a lot of it wrong. People in nonstate societies cooperate extensively with their kin and allies, so life for them is far from “solitary,” and only intermittently is it nasty and brutish. Even if they are drawn into raids and battles every few years, that leaves a lot of time for foraging, feasting, singing, storytelling, childrearing, tending to the sick, and other necessities and pleasures of life.

Oddly, Graeber and Wengrow cite evidence of early peoples caring for the sick and injured to counter Pinker’s findings about prehistoric violence. In other words, they aggressively prosecute Pinker for crimes he did not commit.

Things get worse when Graeber and Wengrow discuss Pinker’s use of the Yąnomamö of southern Venezuela and northern Brazil to illustrate a scenario called the “Hobbesian trap,” or more technically, the “security dilemma.” Imagine a homeowner with a gun encountering a burglar in his house who is also visibly packing. Even though the homeowner may not want to kill anyone over what may be an act of desperation, there is no guarantee the burglar won’t shoot first. Likewise, the burglar may not be apt to kill people who are simply defending their homes, but there is no guarantee the homeowner won’t shoot first. Shooting first becomes the most rational option for both. As Pinker explains:

People in nonstate societies also invade for safety. The security dilemma or Hobbesian trap is very much on their minds, and they may form an alliance with nearby villages if they fear they are too small, or launch a preemptive strike if they fear an enemy alliance is getting too big. One Yąnomamö man in Amazonia told an anthropologist, “We are tired of fighting. We don’t want to kill anymore. But the others are treacherous and cannot be trusted.”

It should be noted here that this is the only mention of the Hobbesian trap in relation to the Yąnomamö in the whole of Better Angels; Graeber and Wengrow, however, insist Pinker cherry-picks this society to support his wider application of a Hobbesian framework.

Graeber and Wengrow botch both their definition of the security dilemma and the explanations of Yąnomamö violence offered by Pinker and Napoleon Chagnon, the anthropologist whose writings inform his theory. Graeber and Wengrow write that:

the Yanomami are supposed to exemplify what Pinker calls the “Hobbesian trap,” whereby individuals in tribal societies find themselves caught in repetitive cycles of raiding and warfare, living fraught and precarious lives, always just a few steps away from violent death on the tip of a sharp weapon or at the end of a vengeful club.

Pinker in fact treats revenge as a separate cause of violence, though he does describe cycles of raids and counterraids as a common outcome. Graeber and Wengrow apply the term “Hobbesian trap” as a catch-all description of a violent society to reinforce their characterization of Pinker as a carrier of Hobbes’s torch. Though, as we have seen, Pinker specifically writes that nonstate peoples were not always “a few steps away from a violent death.”

The closest Graeber and Wengrow get to addressing the statistics underlying Pinker’s argument is to point out that “compared to other Amerindian groups, Yanomami homicide rates turn out average-to-low.” This is an odd point, since Graeber and Wengrow earlier in the section claim that Pinker cherry-picked the Yąnomamö because they are particularly violent. And both Pinker and Chagnon themselves point to the relatively higher rates of violence among other groups to counter such charges of cherry-picking and exaggeration from other critics. Graeber and Wengrow go on to claim:

Chagnon’s central argument was that adult Yanomami men achieve both cultural and reproductive advantages by killing other adult men, and that this feedback between violence and biological fitness—if generally representative of the early human condition—may have had evolutionary consequences for our species as a whole.

Although this is consistent with the view attributed to Chagnon by his critics, it is not quite correct. What Chagnon was really contending in the article Graeber and Wengrow cite was not that the Yąnomamö show us how humans may have evolved to be violent, but that Yąnomamö violence was motivated by individual and family interests—what biologists call “inclusive fitness”—and not by a desire for some other village’s valuable resources. In other words, ironically, Chagnon was challenging some of the same notions about the role of farming and private property that Graeber and Wengrow take Diamond and Pinker to task for accepting, even though those two really don’t endorse these notions either.

Better Angels irked many social scientists and leftist commentators because it reintroduced and vigorously defended the idea of progress in Western history—one of the central ideas Graeber and Wengrow hope to undermine in The Dawn of Everything. Specifically, Pinker attributes the most dramatic dips in the trendlines representing violence to some of the ideas and values that came to prominence during the Enlightenment. Unfazed by the backlash to Better Angels, Pinker doubled down in 2018 by publishing Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, which is full of numerous other trendlines all suggestive of people living longer, safer, healthier, even happier lives than their ancestors—all contrary to the dismal view of life in modern states put forth by Graeber and Wengrow.

Pinker ascribes these improvements to the implementation of ideas that blossomed in 17th and 18th century Europe. Graeber and Wengrow’s counter-assault begins by calling into question Pinker’s presumed politics. If Pinker wants to portray himself as a rational centrist, they ask:

why then insist that all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as “the white race” (and now, generally, call themselves by its more accepted synonym, “Western Civilization”)?

The shift from Pinker’s real argument to Graeber and Wengrow’s straw man entails turning the focus from the ideas of the Enlightenment to the race of the people who first embraced them. But Pinker does not attribute the progress he reports to Western civilization, but to a single current that began to run through it at a certain point in that history.

Graeber and Wengrow’s accusation of racism is a predictable but lamentable outcome of the activists’ imperative to default to the presumed victims’ perspective—which likely also motivated them to make the case that the Enlightenment was largely indigenous peoples’ idea. This same imperative infuses with venom the taboo against suggesting that anything coming from the West might somehow be better than what is on offer in non-Western societies or that anything coming from non-Western societies might somehow be worse. Graeber and Wengrow explain the problem thus:

Insisting, to the contrary, that all good things come only from Europe ensures one’s work can be read as a retroactive apology for genocide, since (apparently, for Pinker) the enslavement, rape, mass murder and destruction of whole civilizations—visited on the rest of the world by the European powers—is just another example of humans comporting themselves as they always have; it was in no sense unusual. What was really significant, so this argument goes, is that it made possible the dissemination of what he takes to be “purely” European notions of freedom, equality before the law, and human rights to the survivors.

Not only is Pinker a racist; he is also an apologist for genocide, slavery, rape, and mass slaughter. This would be outrageous if true, but as should be obvious, it is not.

Graeber and Wengrow conflate Pinker’s celebration of the specific Enlightenment values he lists in his subtitle with the whole of Western civilization. To say that some people, who happened to live in Europe, promoted ideas, which would eventually lead to improved lives for their descendants and others who embraced those ideas, does not excuse the atrocities committed by other people, who also happened to live in Europe at the time. As Pinker writes in Enlightenment Now:

For one thing, all ideas have to come from somewhere, and their birthplace has no bearing on their merit. Though many Enlightenment ideas were articulated in their clearest and most influential form in 18th-century Europe and America, they are rooted in reason and human nature, so any reasoning human can engage with them. That’s why Enlightenment ideals have been articulated in non-Western civilizations at many times in history.

Graeber and Wengrow claim that Pinker argued “‘purely’ European notions” are responsible for making the world a better place, when in fact Pinker explicitly argued the opposite. (Are those supposed to be scare quotes surrounding the word “purely”?) And Pinker certainly never maintained that every European embraced the Enlightenment with equal fervor. He writes:

But my main reaction to the claim that the Enlightenment is the guiding ideal of the West is: If only! The Enlightenment was swiftly followed by a counter-Enlightenment, and the West has been divided ever since.

Graeber and Wengrow argue that the only way to compare two societies is to give people a chance to experience both and then let them choose in which one they would prefer to live. They go on to assure readers that “empirical data is available here, and it suggests something is very wrong with Pinker’s conclusions.” Here’s what they mean:

The colonial history of North and South America is full of accounts of settlers, captured or adopted by indigenous societies, being given the choice of where they wished to stay and almost invariably choosing to stay with the latter. This even applied to children. Confronted again with their biological parents, most would run back to their adoptive kin for protection. By contrast, Amerindians incorporated into European society by adoption or marriage, including those who … enjoyed considerable wealth and schooling, almost invariably did just the opposite: either escaping at the earliest opportunity or—having tried their best to adjust, and ultimately failed—returning to indigenous society to live out their last days.

If empirical evidence supported the claim that European settlers and indigenous people alike “almost invariably” prefer to live in indigenous societies, then that would be suggestive. Of course, people may choose to live in a society with a shorter life-expectancy and other drawbacks for many reasons. For instance, they may have fallen in love. Or they may be wanted for a crime back home. Or they may be more familiar with their environment and afraid of change. Nevertheless, when comparing societies, the tendencies of people to stay or leave, to praise or criticize, are certainly relevant data.

But Graeber and Wengrow’s source was a 1977 thesis by Joseph Norman Heard which offers a qualitative, not a quantitative analysis. And there are as many descriptions of captives returning to their society of origin as there are of people becoming assimilated into the society of their captors. Although Heard does quote a few scholars who make claims that are superficially similar to Graeber and Wengrow’s suggestion that settler and native alike prefer indigenous cultures, his own assessment of the evidence is almost the opposite of Graeber and Wengrow’s interpretation. Heard summarizes a section examining the factors that go into determining whether a captive became assimilated like this:

It was concluded that the original cultural milieu of the captive was of no importance as a determinant. Persons of all races and cultural backgrounds reacted to captivity in much the same way. The cultural characteristics of the captors, also, had little influence on assimilation.

According to Heard, “It was concluded that the most important factor in determining assimilation was age at the time of captivity.” Heard reports that children captured before puberty almost always became assimilated—recall Graeber and Wengrow’s line, “This even applies to children”—while those captured after puberty usually wanted to return to their society of origin. This was the case for settler and indigenous children alike.

Thus, Graeber and Wengrow’s argument against Pinker’s case for progress severely distorts his actual position and misrepresents a doctoral thesis from over 40 years ago to undermine a claim of Western superiority Pinker never made. When historian Daniel Immerwahr pointed out in a review for the Nation that the characterization of Heard’s findings in The Dawn of Everything is “ballistically false,” Wengrow took to Twitter to try to salvage the point by highlighting individual lines. Pointing only to the numbers cited in Heard’s thesis, Wengrow argued that Heard had failed to consider a large enough sample. But using these numbers reveals that at least 28 percent of captives failed to become fully assimilated; the true number is probably closer to 91 percent. Wengrow concluded his thread by reminding his followers what is at stake: “for context, our point here was to refute Pinker’s suggestion that any sensible person would prefer Western civ to life in (what he calls) ‘tribal’ societies.” No citation is provided to point readers to where Pinker makes this suggestion.

What makes all this ax-grinding and all these extra-scientific concerns so frustrating is that Graeber and Wengrow had a wonderful opportunity to write about a fascinating and quickly growing science. Their discussion of “culture areas” and “schismogenesis”—whereby one society consciously defines itself and its values in opposition to another neighboring society—is both riveting and persuasive. Yet their efforts are marred by unnecessary ad hominem attacks and straw-man arguments, all of which lend weight to the impression that the authors are more concerned with their political agenda than with the science.

While it is of course true that every scholar who writes a book has political concerns, including Diamond and Pinker, the important question is whether those concerns take precedence over truth-seeking. Those whose priority is finding and sharing the truth will report evidence that contradicts their preferred political narrative candidly and accurately. Those whose priority is to push a political narrative, on the other hand, will neglect or distort sources that challenge it. And this robs the scholarly and the lay community of that most precious of intellectual resources: Honest debate.