Politics

China in the Age of Surveillance

China’s security apparatus may not be able to see into the minds of the people, but it can make their lives a misery in the attempt.

He could feel the State’s bright eyes gazing into his face.

~Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

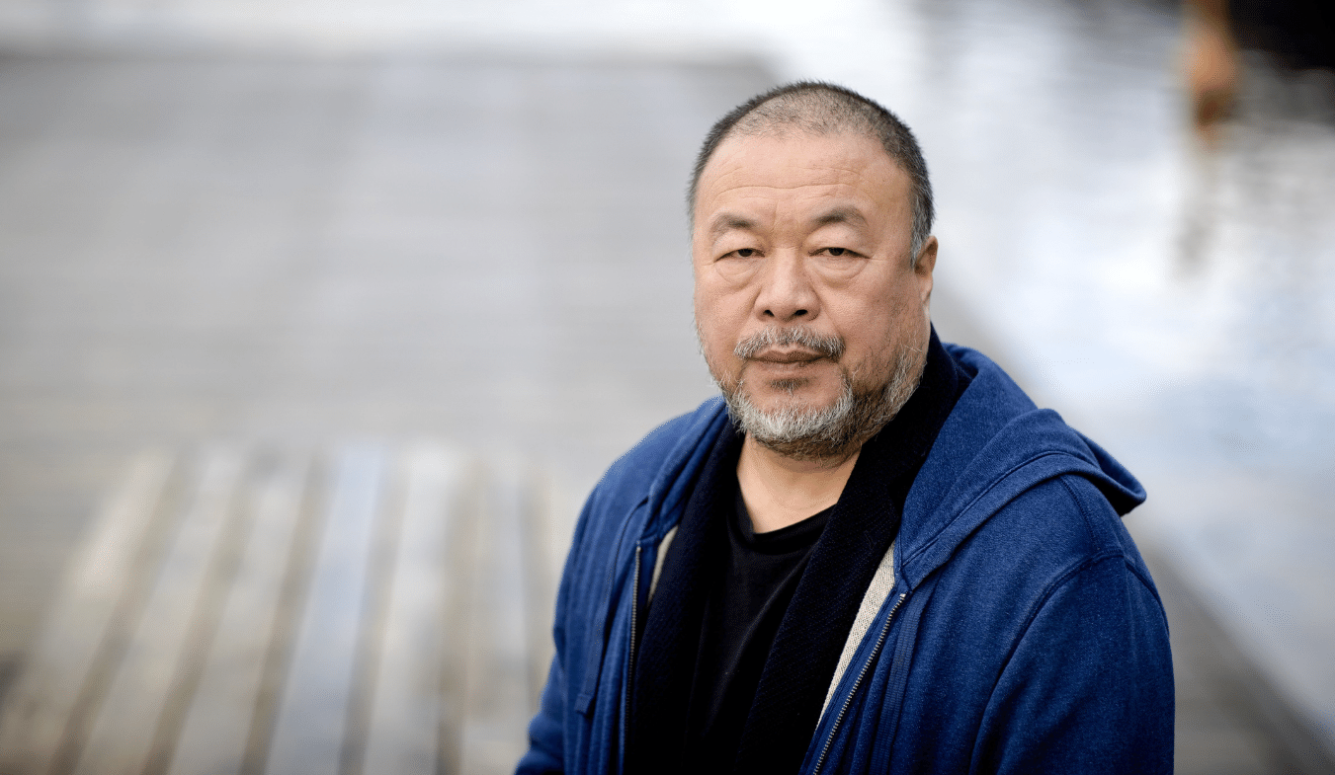

On April 3rd, 2011, the Chinese artist and outspoken dissident Ai Weiwei was apprehended by a large crowd of police at an airport in Beijing. Nothing at all was heard from him for the next three months. I still remember my own fear at the time: I knew details, unfortunately, of the various and barbaric tortures previously inflicted on dissenters like Gao Zhisheng. But when the artist re-emerged in June, he said that he had not been physically abused. Instead, he had been kept in a tiny room under 24-hour bright lights, always accompanied by two silent policemen. They would stand and watch Ai as he slept and showered and used the toilet. Every 12 hours, the shift would end and two new policemen would take up their positions. This peculiar form of psychological torture continued for 81 long days.

The purpose, we must assume, was to instil in the artist’s mind a sense of being permanently watched. For the rest of his life, whenever he began planning an art piece or dissident activity, he will be unable to shake the feeling that the eyes of the authorities are boring into his skull. The experiment’s success was questionable: after his release, Ai rigged up four surveillance cameras outside his Beijing home in apparent mockery. He also created the installation “S.A.C.R.E.D.” (“Supper, Accusers, Cleansing, Ritual, Entropy, Doubt”) consisting of realist models of Ai and his captors positioned in a variety of scenes inside six shoulder-height replicas of his detention cell. Ai Weiwei left the country for good in 2015, but seven years on, his surveillance-themed works are more appropriate than ever. Ai’s experience in detention was really a harbinger for the Chinese people; a microcosm of the nation’s future. Today, Xi Jinping is creating the most heavily-surveilled state in history.

There are now an estimated 540 million CCTV cameras in China. Cameras watch citizens as they shop and dine. Cameras stare at residents as they leave home in the morning and return at night. In the office, cameras spy on workers inside toilet cubicles. And if you, the Chinese citizen, are particularly unfortunate, you may arrive home one day and find that a camera has been installed within your property. Supposedly a quarantine measure, it crouches there on the cabinet wall like a hostile creature that has somehow found its way in—watching as you eat, watching as you watch TV; a silent, unwanted houseguest. Cameras also lurk in the homes of the mentally ill. The state considers them too volatile to live unmonitored, but no apparent thought has been given to the special torment produced by an ever-present eye during periods of psychological distress.

A Chinese company in Xiamen installed surveillance cameras inside toilet cubicles to monitor its staff. A viral image on Weibo showed photos it took as evidence and staff caught smoking were fired as punishment. pic.twitter.com/RD9xtSuGYj

— Rachel Cheung (@rachel_cheung1) September 14, 2022

China is home to eight of the world’s 10 most surveilled cities (the luckless occupants of Chongqing live at number one). And the surveillance camera of 2022 is a very different animal to the one we remember from our childhoods. It has evolved a whole new set of features: facial recognition, gait recognition, body scanning, geo tracking. Police in Zhongshan city are now using cameras that can record audio within a 300-foot radius. Their plan is to analyse the audio using voice recognition software and then combine the results with that same camera’s facial recognition data, quickly identifying targets.

The nation’s schoolchildren are monitored throughout the day. Party media reports that cameras record students’ facial expressions and log “whether they look happy, upset, angry, fearful, or disgusted.” Some will learn, of course, to mask their feelings permanently. But others won’t be able to preserve that private space. They will internalise the watching eye of the authorities, like a grotesque Freudian superego, and their thoughts will never really be their own. Schools down in the southern regions of Guizhou and Guangxi have taken an extra step toward dystopia. Should any of their students manage to slip away from the cameras’ gaze, an alarm will be triggered—uniforms now come with microchips in the shoulders.

The eyes of the Party hang above and all around as you walk through the city, but they also peer out from your jacket, your jeans, your purse. Smartphones have become all but indispensable in China. Most people use Alipay and WeChat for everything from flight tickets to family shopping, from their morning coffee to their monthly bills, and the CCP is making full use of this opportunity to harvest data and monitor online behaviour. COVID-19 has proved a blessing for Beijing: health-code apps help the authorities to stalk a person’s movements. In Xinjiang, where the surveillance state has ruled longest, Uyghurs long ago resorted to burying their phones in the back garden and freezing the data cards inside dumplings.

That smartphone in your pocket is like a bright flashing beacon to the Party’s ubiquitous phone tracking devices, which lurk within cameras, or nearby, resembling WiFi routers. The trackers hunt for specific red flags such as Uyghur-to-Mandarin dictionary apps, which would identify the phone owner as a member of the oppressed Uyghur ethnic group. But they also scour your mobile for personal details like social media usernames, regardless of your ethnicity. Some of the trackers are called “WiFi sniffers,” hiding on public WiFi networks to spy on phone activity. Others are called “IMSI-catchers.” They masquerade as mobile towers, luring your phone into making a connection. Once connected, your personal material can be raided, your conversations tapped, etc.

The CCP has always suffered from a lack of legitimacy (the Party seized power, rather than winning an election), and as a consequence, it relies on implicit social contracts. For the past three or four decades, the contract has involved large numbers of people getting rich at a pace for which history provided no precedent. But those days are over. China’s economy is now facing insurmountable difficulties, and so the contract has been rewritten. Instead of riches, the Party promises safety—the tightest and toughest security in the world.

Officials trumpet the successes of AI-powered surveillance, most of which we might charitably describe as modest. A decline in unlicensed street vending; less garbage on the streets; more responsible parking of electric bikes. Very occasionally there will be a genuine success—cameras will locate a missing child. Such cases are heavily publicised, along with reports of a rise in detention numbers, dubiously equated with a rise in general safety. All these successes distract from the main issue: invasive surveillance is fast becoming a feature of life for Chinese citizens. In Wuhan, parents take their children to data collection points for iris scans. In Xinjiang, travellers applying for passports are required to provide voice samples. In Zhengzhou, residents queue outside apartment blocks, waiting to have their faces scanned in order to enter their own homes. Everywhere, the masses surrender their biometric markers. And up above, drones disguised as doves hover in the smog, watching.

The Party is pumping tens of billions of dollars into the creation of what it calls “safe cities.” They will be safe because authorities will enjoy “100 percent coverage,” pooling the information from swarms of smart cameras and phone trackers with 63 different types of police data and a further 115 varieties of data from other government departments—medical history, family relations, religious affiliations, flight records, hotel records, and so on. The systems will hoard data from QR code readers; point-of-sale machines; air-quality monitors.

China’s police have also been taking every opportunity to collect male Y-chromosome DNA. Their reasoning is as follows: the Y-chromosome picks up relatively few mutations from one generation to the next, so the profile of one man is effectively the profile of multiple males along the same paternal line. Extensive Y-chromosome DNA records should help the authorities to capture a broad snapshot of any male suspect’s family history and geographic ancestry. And so the chilling instructions to police in Gansu province: “Do not miss a single family in each village. Do not miss a single man in each family.” In the view of the Party, as expressed by a former Minister of Public Security, all this big data will make it possible to literally “pinpoint a person’s identity.”

Soon, AI-powered platforms will manage cities, controlling everything from urban planning to electricity consumption to firefighting. Of course, these “safe cities” will just ensure that few people are safe from the authorities and the unsleeping bright eyes of the State. Hangzhou provides a snapshot of the future. China’s tech giants practically run the city, but they are required to share their data with the government so it can be combed for “threats to national security.” In the eyes of a fanatical, paranoid, illegitimate regime, almost any behaviour could fall into this vast elastic category.

And other dangers await today’s Chinese citizen. Oddly juxtaposed with all that efficiency, we find the cack-handed sloppiness and corruption that has always followed the CCP. Those vast vaults of data are typically stored on unprotected servers. For a price, details will sometimes be handed over to fraudsters or suspicious spouses. Earlier this year, hackers were able to snatch the personal details of almost a billion Chinese citizens from a Shanghai police database—perhaps history’s biggest personal data heist. The dashboard for accessing the information had been set up on a public web address and left open without a password.

A surveillance state run by incompetents is still immensely dangerous. And Xi’s techno-totalitarian reach stretches far beyond China’s “safe cities” and the country’s borders. The so-called Digital Silk Road unspools across the map in all directions. AI-enhanced cameras are sold to Malaysia in the south and Mongolia in the north. They are shipped out across the Indian Ocean to Sri Lanka. Further west, they are reaching African shores: Egypt, Kenya, Mauritius, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe. On the far side of the world, with the help of Chinese loans, they are now arriving in Ecuador and Bolivia. Safe cities are even coming to Europe, where Serbia’s combination of AI-cameras with joint patrols by Serbian and Chinese police has been specifically designed to make Chinese tourists feel secure; to feel they are still in China, to feel the eyes have never stopped watching them. In fact, the same surveillance tech aids police forces on every continent except Australia and Antarctica. This is not just good business; the Communist Party controls the networks and their data.

At exhibitions in Shenzhen and Beijing, companies like Huawei, Hikvision, SenseTime, and YITU display the latest surveillance technology, hoping to woo buyers both domestic and international. CEOs rhapsodise to their audiences about the dystopian state they are helping to build (and the West has also helped with this project, lest we forget: China’s safe city industry has plenty of commercial and supply-chain links to US companies). “Over the next twenty to thirty years human society will enter a smart era with omnipresent sensing, all-connectivity, and pan-intelligence,” Huawei executive director Wang Tao enthused at the China Public Security Expo in 2019.

The next frontier will be micro-expression and emotion-recognition tech. Financial services conglomerate Ping An has begun assessing loan applications with futuristic lie detectors. Ping An boasts that 54 tiny, involuntary facial movements can now be identified in the fractions of a second before the brain assumes full control, allowing for a detailed analysis of whether or not the applicant is being truthful. Meanwhile cameras probe faces at customs, searching for hints of stress or nervousness. The direction is clear: Beijing is attempting to transform into reality that old dystopian trope of thoughtcrime. By sifting through the mountains of data collected on each citizen, policing software can begin to determine patterns of behaviour and intervene in crimes that the perpetrator has yet to plan.

But the truth is that none of the flashy tech does what the Party thinks it does. There is no such thing as a reliable mind-reading machine. The convoluted motivations and inner world of a human being could never be reduced to eye movements and facial twitches and stress signals, all recorded and categorised by blind, unknowing artificial intelligence. (The only thing that can read a human mind is another human mind: instinctively, in the moment, with little or no understanding of the process.) We are witnessing an attempt to define people in purely rational terms—a variation on the same myopic mistake that Communist Parties have consistently made, all over the world, for a hundred years. They have always failed, and now this Party will fail once again, because human beings are not machines.

With such failure comes collateral damage. If mannerisms are signs of guilt, then the detentions will never end. The CCP’s paranoid police force already arrests citizens for such depravity as “frequent entry into a residential compound with different companions.” And most arrests already lead to a prison sentence, for the simple reason that torture is typically used to wrench confessions from detainees. Now the new technology is arriving—a technology for which success is measured in the numbers of suspects identified and detained. China’s prisons have always heaved with innocent people; they will need to build many more.

In the name of order, the Party is delivering chaos. But for all the blundering, Xi’s surveillance state still threatens a closer approximation of true totalitarianism—which means a fuller denial of human liberty—than any previous regime has managed. Neither Stalin nor Mao could look directly into the daily movements, words, and transactions of their subjects like Xi can. Those leaders had agitprop, re-education camps, the Red Guards, the Gulag; Xi has artificial intelligence and big data. There is no competition. China’s Intruder-in-Chief may not be able to literally see into the minds of the people, but he can make their lives a misery in the attempt.

The surveillance state watches everyone. There is, however, a blacklist consisting of those who require particular attention, and it’s a long one. It extends from fugitives and suspected terrorists all the way through to migrant workers, the mentally ill, and foreigners. (There is also a redlist: government officials, secret police, intelligence agents—the people whose behaviour must never be flagged, no matter how unorthodox.) But the state is most interested in the country’s dissenting voices.

China has rarely been without its dissidents: those men and women who rise above the herd and stubbornly refuse to be quiet and accept their fate. The Ai Weiweis; the Chen Guangchengs; the Zhang Zhans. They imbibe the same childhood propaganda as everyone else, but to the eternal bafflement of the authorities, they don’t turn out the same as everyone else. Zhang Yuqiao has lived for as long as the Party has ruled, and he is one such exception. For decades, Zhang has been petitioning the government—first seeking redress for the torture of his parents during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and later protesting police harassment of his family.

Up until very recently, when making his trips from Shandong to Beijing to raise his complaints, he needed only to stay off the main roads in order to avoid police interception. Now his task has become more complicated. Before heading to Beijing, Zhang turns off his phone, buys multiple train tickets to the wrong destinations, and hires private drivers to get him round the numerous police checkpoints that spring up today like malign growths all over China’s highways. He would have no chance of making it through one of those checkpoints, not with the new technology in place.

But this is another crack in the façade of the surveillance state: simple, stubborn human ingenuity, as displayed by Zhang Yuqiao. There will always be some who manage to work around the restrictions. And even in dystopian Xinjiang, pockets of privacy can be found. Personal cars, thickly crowded marketplaces, remote stretches of desert—there are places beyond the eyes and ears of the Party; places where information can be shared and plans made. Xi Jinping wants omniscience, but he won’t find it.