The Agony of the Putin Regime

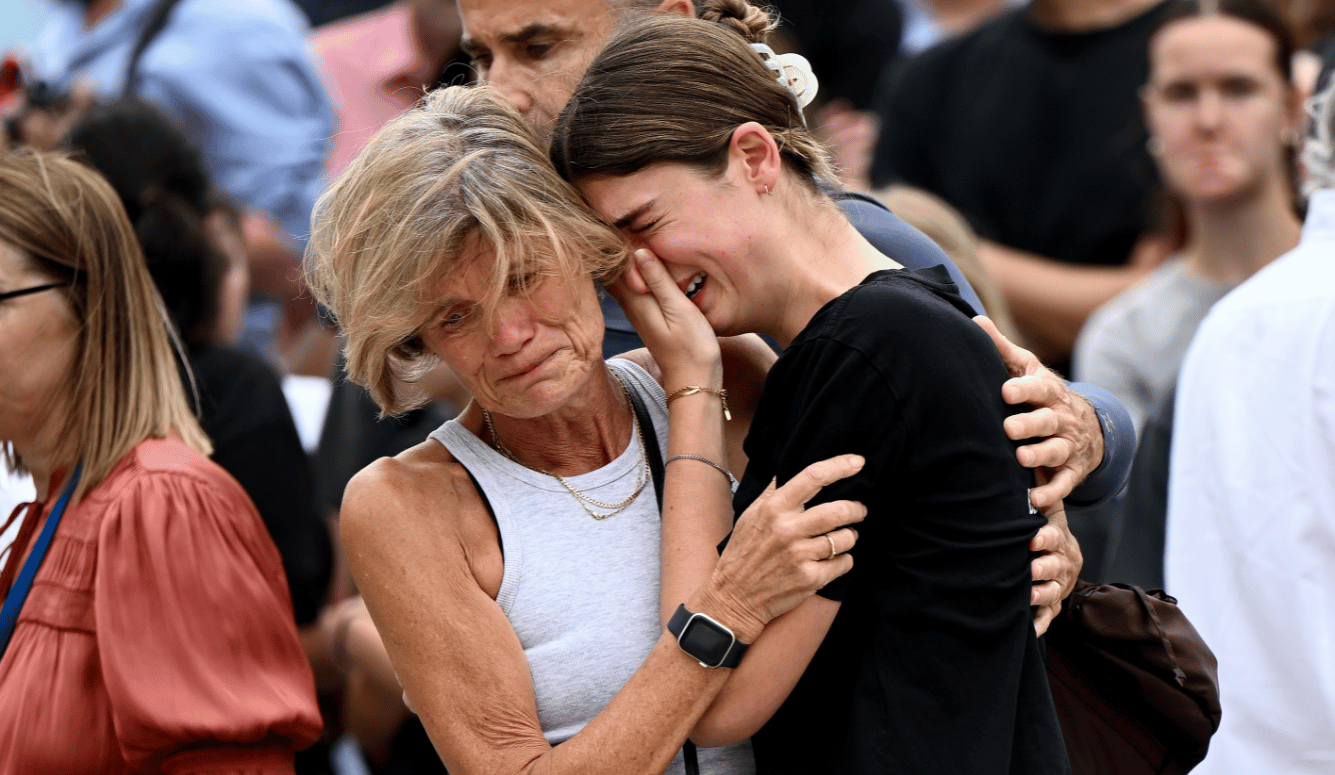

The explosion in Moscow in which Darya Dugina lost her life shows the limits of Putin’s totalitarian domination.

From the very outset, terror was a main feature of Bolshevism. Echoing Marx, Lenin criticized the otherwise sanctified Paris Communards for having failed to eradicate the accursed bourgeois enemies. At that moment, Fanya (Dora) Kaplan, the 28-year-old quasi-blind Socialist Revolutionary former political prisoner and survivor of the most ruthless jails in the czarist repressive system (katorgas), shot the dictator on August 30th, 1918.

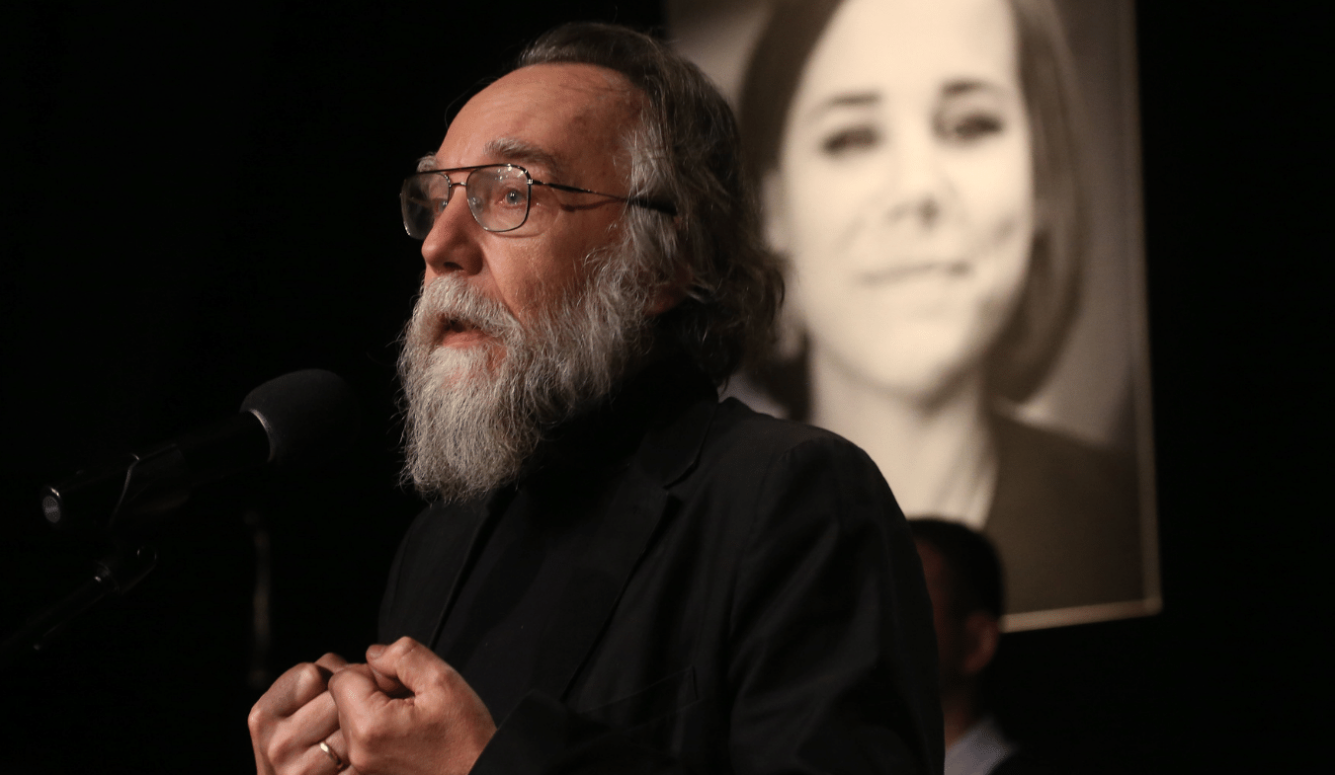

The Bolsheviks were thus given the propaganda ammunition to unleash mass terror. The Cheka was born as the “sword and shield of the Revolution,” while Kaplan was expeditiously executed. In his novel Europe Central, William Vollmann made her a very strange, enigmatic character. The late Harvard historian Richard Pipes expressed some doubt regarding the Cheka’s official story about the attempt on Lenin’s life. So, the FSB narrative about a young woman from Ukraine who entered the Russian Federation in July to organize a terrorist attack on Darya Dugina, or maybe on her father, the eccentric “philosopher” and fascistic ideologue Aleksandr Dugin, is not without precedent.

I’m not saying Kaplan was killed on false charges. All I’m trying to say is that the assassination attempt was assigned to her without any investigation. Also revealing to me is the fact that the Leningrad boys (the siloviki) grew up in a city once run by one of Stalin’s closest associates, Old Bolshevik Sergei Kirov, who was himself assassinated on December 1st, 1934. Putin’s circle of Leningraders includes his closest associate, Nikolai Patrushev, and the former façade president, Dmitry Medvedev.

On August 21st, 1968, the USSR crushed the audacious reformist experiment known as the Prague Spring. That year, a 16-year-old high school student from Leningrad named Vladimir Putin decided to pursue a KGB career. Now, Putin is Russia’s autocrat, and his opponents are besmirched, harassed, jailed, and murdered. Democratic activist Alexei Navalny fell into a coma, most likely as a result of poisoning, in a strictly supervised hospital in Omsk. His “crime”? Fighting for human rights, civic dignity, and the rule of law. I have great admiration for Navalny, Vladimir Kara-Murza, and the beleaguered democrats in Putin’s police state.

The explosion in Moscow in which Darya Dugina lost her life shows the limits of Putin’s totalitarian domination. Using Hegel’s image, the old mole is working for freedom, not for the heirs of Yagoda, Yezhov, Beria, Shelepin, and Andropov. For all intents and purposes, Putin and his gang have not succeeded in their war on Ukraine. No matter what their rabid propagandists say, Putin has miscalculated the war militarily, geopolitically, psychologically, morally, and culturally.

The only outcome for such a debacle cannot but be a dramatic and, yes, inevitable regime change. This dictatorship came into being by using the scarecrow of terrorism. When apartment buildings were exploding in Moscow in 1999, the ostensibly self-effacing Putin postured as a guarantor of stability. The “Family” (Yeltsin’s daughter Tatiana and her husband Valentin Yumashev) plus the two most influential oligarchs (Roman Abramovich and Boris Berezovsky) selected him as heir to the throne. The terminally sick Yeltsin acquiesced. The current spasms could be the end of a Time of Troubles or the beginning of a new one. One thing, however, is sure: Putin will never again enter a car without a strong, excruciating sense of fear—unless, of course, he was behind the explosion.

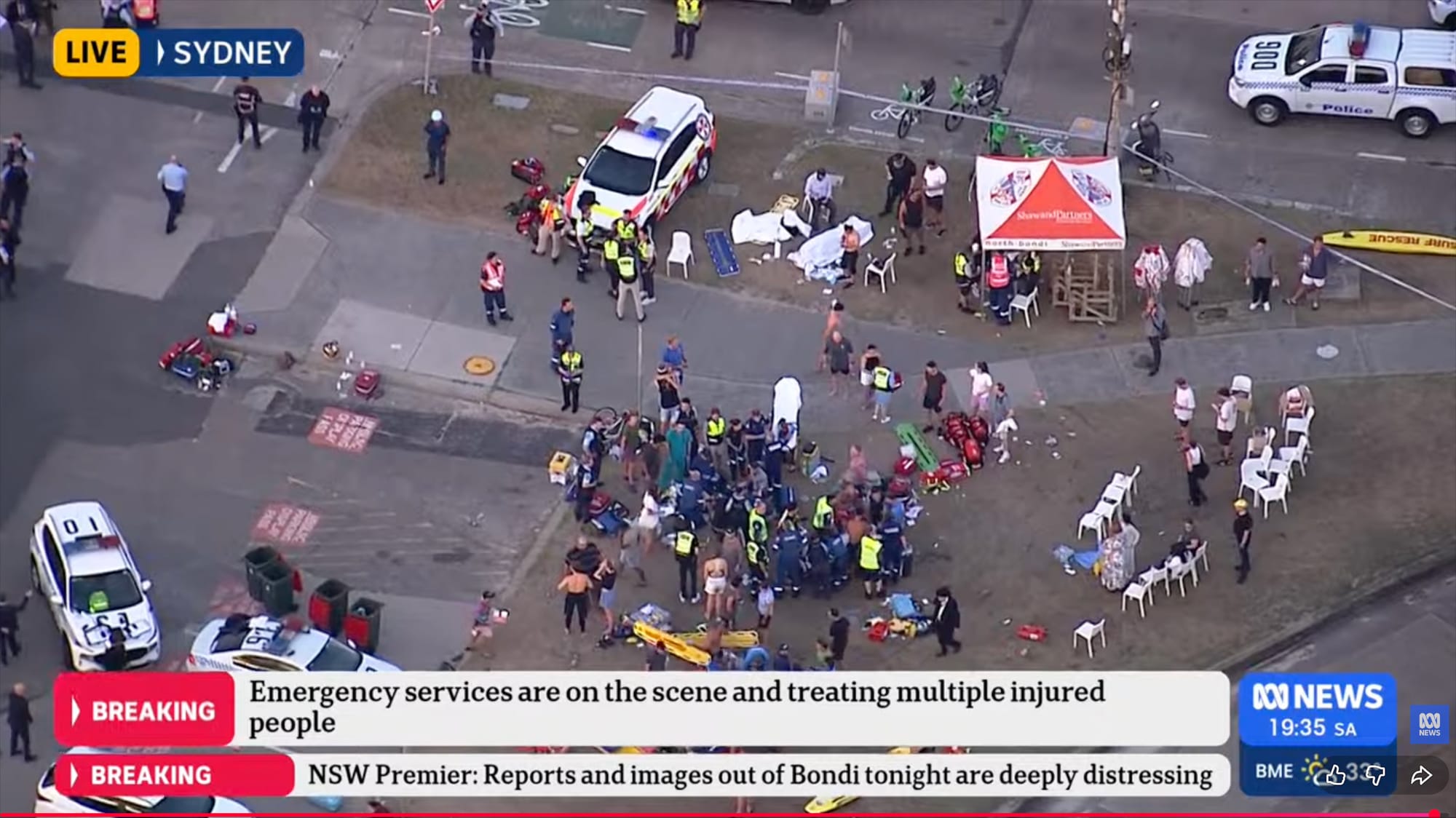

Car explosion kills Daria Dugina, daughter of Russian nationalist known as "Putin's brain" - CBS News https://t.co/PAX1VmIYKT pic.twitter.com/vsLPNfNDnk

— Noah Ross (@drnoahross) August 21, 2022

To the extent that Putin can digest philosophical ideas, one can say that he’s in love with the late émigré thinker Ivan Ilyin’s Weltanschauung. Putinism is obsessed with Russia’s Lebensraum. Like in Nazi Germany, Russian geopolitical circles provide the ideological pills that nourish the neo-imperialist imagination. All that remains of the myths of ur-Bolshevism is a spurious and specious Messianism. Russian Fascism, like the German, Italian, and Romanian versions, is rooted in those currents that have justified, promoted, and advocated rebellion against bourgeois modernity. It is the revolt of the allegedly pristine heroic-popular community (Volksgemeinschaft) against the polluted and polluting, corrupt and corrupting, perverse and perverting capitalist society (Gesellschaft).

Someone like Aleksandr Dugin resuscitates the Fascist phobias, taboos, and totems from the interwar ideologues such as Julius Evola, young Emil Cioran, and Mircea Eliade, as well as their mentors Nae Ionescu, Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, and the whole anti-Enlightenment tradition. Add to these names that of oracular esotericist René Guénon and we enter the territory of a dark theoretical continent. During the interwar period, Romania had the third-largest Fascist party movement in Europe. Founded and led by the charismatic Capitan Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, it championed the need for a spiritual opposition to the decadent democratic order. Like the Black Hundreds in czarist Russia, it invoked the Archangel Michael as its patron saint.

Dugin’s fascination with the doctrinaires of the Iron Guard originates in his deep interest in Evola and his friendship with the strange far-right mystical novelist and self-styled prophet Jean Parvulesco, author of an arcane, rambling Putin biography with a foreword by Dugin.

In an essay published in Partisan Review and included in the anthology A Partisan Century, I proposed the concept of mystical revolutionaries to highlight the alliance between religious fundamentalism, antisemitism, and anti-capitalism in the name of an authoritarian collectivist national resurrection. Terms such as redemption, expiation, blood and soil, and martyrdom figure prominently in the apocalyptic tenets of Putinism. One of the best analyses of the collapse of the USSR remains Stephen Kotkin’s Armageddon Averted.

Yet, at this point, in light of the war against Ukraine, one may be justified in doubting that catastrophe will be avoided. Vladimir Putin was born on October 7th, 1952, in Leningrad. Joseph Stalin passed away on March 5th, 1953, in Kuntsevo, near Moscow. Ivan Ilyin died in 1954. A fantasy of salvation if ever there was one, Putinism is a syncretic construct in which megalomania, paranoia, and excruciating inferiority complexes generate explosively destructive passions. It is both romantic resentment and resentful romanticism.

Esotericism is a radical right intellectual enterprise. What Dugin has been doing is mixing it with Eurasianism and Slavophile tradition. It is a revolutionary project, or, using historian Roger Griffin’s concept, a palingenetic endeavor. The world is degenerate; it needs to be regenerated. It is decrepit; it requires rejuvenation. It aims to reconstruct a lost paradise, to reconcile the sacred and the profane.

Several years ago, Ukrainian hackers published Dugin’s list of agents in Romania. The Kremlin has always had interests in the Balkans, especially in Romania, Bulgaria, and Serbia. Christian Orthodox mysticism is a significant ingredient. In my opinion, Duginism is a political fundamentalism. It is one of the currents that make Putinism an ideology with transnational appeals.

Take the case of Romania. Among Dugin’s Romanian partners, three strike me as worth mentioning. First, the politician Adrian Năstase, once chairman of the Social Democratic Party (member of the Socialist International), prime minister, and presidential candidate, arrested and condemned for corruption, and currently the manager and organizer of high-profile programs at the Association of International Law and Relations in Bucharest. Second, the sociologist and geopolitician Ilie Bădescu, former director of the Institute of Sociology, a corresponding member of the Romanian Academy, and the main proponent of Dugin’s “scholarship” in Romania. In the 1980s, he was one of the most vocal proponents of “protochronism,” a quasi-official ideology claiming Romanian precedence in arts and science and legitimizing Nicolae Ceaușescu’s pre-Christian and medieval fantasies. Third is graphic artist Eugen Mihăescu, a regular art contributor to the New York Times and the New Yorker in the 1980s. After 1989, he returned to Romania, became a vocal sycophant of President Ion Iliescu, ambassador to UNESCO, then a senator in the rabidly xenophobic Greater Romania Party, and is now a Dugin fan in Romania. The links to the nationalist, anti-Western, Third World-ist ideology of the Ceaușescu regime are unmistakable.

How, when, and why did Putin espouse this delusional mishmash? How can one explain the rapprochement between the Bolshevism of the far Right, to use historian Robert C. Tucker’s concept, and the kleptocratic oligarchy whose protector is Putin himself. I recommend here the seminal book Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? by the late Karen Dawisha. Her analysis of Putin’s years in East Germany as deputy KGB station chief in Dresden highlights his fear of a civic upheaval and his desire to avoid a liberal revolution in the Soviet Union. This is the real meaning of his oft-quoted statement that the collapse of the USSR was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century. As a teenager, Vova Putin admired a political thriller TV series—“Seventeen Moments of Spring”—about an imaginary Soviet agent who had managed to penetrate Hitler’s inner circle. Played by the iconic actor Vyacheslav Tikhonov, the heroic character Max Otto von Stierlitz excited young Putin’s imagination more than any other cultural archetype. Many teenagers dream of great achievements and project themselves in some figure to be admired for courage, intelligence, sagacity, and wisdom. For Putin, the idol was the hyper-rational, cunning, invincible spy. In Putin’s own words: “What amazed me most of all was how one man’s effort could achieve what whole armies could not.”

In the much-acclaimed series, Stierlitz was an SS promoted to an SS Standartenführer, the equivalent of colonel. In the KGB hierarchy, Putin reached the rank of podpolkovnik, the equivalent of lieutenant colonel. He imagines himself as the predestined, infallible, omnipotent, visionary genius, a combination of Ivan the Terrible (hence his reliance on the secret police), Peter the Great (hence his imperial expansionism), Joseph Stalin (hence his embrace of Stalin’s chief ideologue Andrei Zhdanov’s exaltation of Soviet-Russian superiority to the decaying West), and, of all Stalin’s successors, Yuri Andropov, the Leninist ideologue and KGB chairman during the invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Is Putin a Russian chauvinist? Is he a convinced Fascist? I remember Yugoslav philosopher Svetozar Stojanović’s response to my question regarding whether Serbian dictator Slobodan Milošević was a radical nationalist: “No, he is a radical opportunist.” This diagnosis strikes me as a key to unraveling the carefully manufactured Putin conundrum. Yet, as we know from the Yugoslav debacle, and as we’ve seen in Chechnya, Georgia, and, now, most ferociously in the war against Ukraine, such individuals can beget unspeakable havoc. Surrounded by scared bootlickers and a hostage to his own vindictive hallucinations, Putin is a scared despot. On October 7th, he will turn 70. October 7th, 1949, was the day when the German Democratic Republic was established. It claimed to be “the first German state of the workers and peasants.” This was, of course, a big lie. As big as Putin’s claim that Ukraine is Russia.

Fear of humiliation by others leads to the need to humiliate, persecute, and even destroy the challengers. Of all the things that Lev Trotsky said about him, nothing annoyed Stalin more than having been called “the most blatant mediocrity on the Central Committee.” The Soviet propaganda state was dedicated to fostering the Stalin myth. Boris Souvarine, a former French communist of Russian origin and a luminary of the anti-totalitarian Left, published his Stalin biography in 1935. It is still one of the most illuminating ever written. He liked to quote this passage from Chateaubriand. It is about the vainglorious dreams of any tyrant, Putin included:

When in the silence of abjection, the only sounds that can be heard are the chains of slaves and the voice of the collaborator, when everything trembles before the tyrant, when it is as dangerous to curry his favor as to merit his disgrace, the historian appears, charged with the vengeance of the peoples. Nero prospered in vain, for Tacitus was already born during the Empire; he grew unknown beside the mortal remains of Germanicus, and already Providence, true to her character, had given to an unknown child the glory of the master of the world.