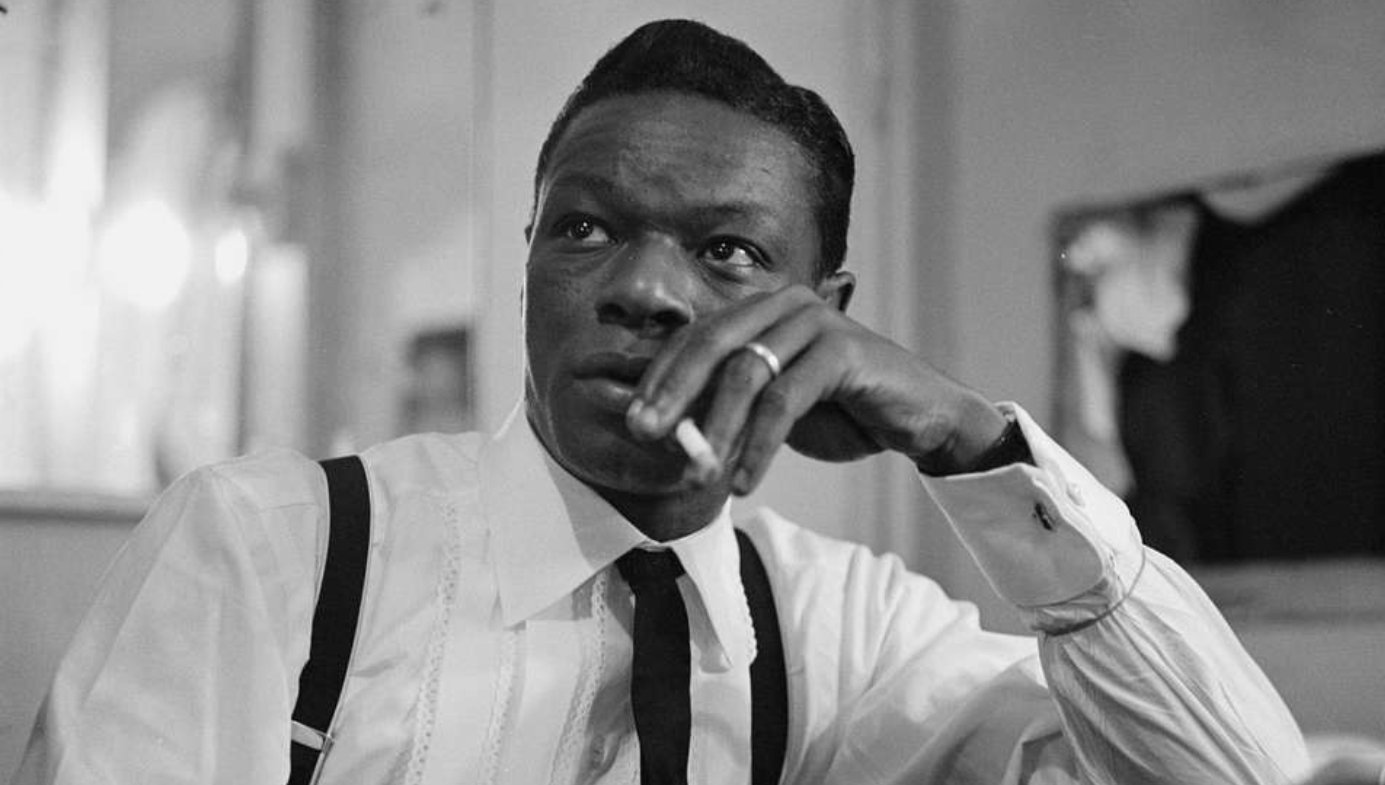

The date was April 10th, 1956. The place was the Municipal Auditorium in Birmingham, Alabama, and the performer, Nat King Cole—singer, composer, and pianist, a laid-back, smile-inducing entertainer beloved by audiences both black and white. Although, evidently, not all whites.

Cole was at the microphone beginning his third song of the evening (‘Little Girl’; not one of his “unforgettables”) when five men raced across the stage yelling racial slurs. One of the assailants lunged at his knees, knocking over the mike stand and sending the singer falling backward onto a piano bench.

In the annals of violence done to the bodies of black folk in Alabama, the assault on Cole is a mere blip. His chin was scratched by the mike and his back was wrenched in the fall. Still, the assault reverberated nationwide, generating outraged headlines and angry editorials. Americans—even many in the Deep South—seemed shocked at a hatred that ran so deep it breached the invisible barrier between performer and audience. Then, as now, no one wanted a zone viewed as a safe haven from the turmoil of the outside world disrupted by a bunch of yahoos on a mission.

Skin color aside, Cole was an unlikely target for racial hatred. No one in show business possessed a more congenial personality or higher likability quotient. What critics called the “hi-fi silkiness” of his expressive voice sent out no angst or edge. “The King is preeminently a stylist—not only in his unique vocal delivery but in the polished projection of a keenly-honed personality which hardly anyone else in the entire theater firmament even remotely resembles,” gushed Variety.

Born on March 17th, 1919, in Montgomery, the old capital of the Confederacy, 90 miles south of Birmingham, Cole was a product of that great incubator of black musical talent, the church. He was the son of a preacher father and a choir director mother. By high school, he was the leader of his own 14-piece band, reason enough to assume the regal nickname. In 1937, he sold his first song (‘Straighten Up and Fly Right’) for $50 to Capital Records, which netted $20,000 on the deal. No hard feelings, apparently, for Cole stuck with the label forever after.

In 1942, Cole scored his first big hit (‘Sweet Lorraine’) and was off and running with a string of chart-toppers (‘Route 66’ [1946], ‘Mona Lisa’ [1950], ‘Too Young’ [1951]) that remain in heavy rotation on easy listening radio, especially at Christmastime (‘The Christmas Song’ [1947], ‘Frosty the Snowman’ [1951]). Cole’s sensuous phrasings—his vocal range was only two octaves—also proved pitch-perfect for the 12-inch vinyl record, the new medium for private listening sessions. Many a white suburban dad cued up Cole albums like Unforgettable (1954) or Nat Cole Sings for Two in Love (1955) and imagined himself in a smoky nightclub with a dolled-up dame. Many a white suburban mom imagined her own kind of scenario.

It was precisely that cross-racial attraction—and Cole’s languid sexuality—that so enraged the guardians of Jim Crow in postwar Dixie. By 1956, the laws and customs that had been inviolate since the Reconstruction era were suddenly threatened by Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Cole understood that when certain Southern white men “looked at me, they saw the Supreme Court and the NAACP.”

The thugs who attacked Cole were members of the North Alabama White Citizens’ Council, a kind of civilian auxiliary to the Ku Klux Klan—like the KKK but without the white sheets or burning crosses—what today would be called a domestic terrorist group. Its executive secretary was a charismatic race-baiter named Asa Carter. Though lunatic, Carter was not fringe. He would go on to become an advisor to and speechwriter for Alabama governor George Wallace, penning the immortal phrase Wallace bellowed at his inaugural address in 1963: “Segregation now … segregation tomorrow … segregation forever!”

In 1973, proving there are indeed second acts in American life, Carter left Alabama, assumed the alias of Forrest Carter, and remade himself as a successful novelist. He was the author of the source novel for Clint Eastwood’s revenge western The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and the fake Indian memoir The Education of Little Tree, published in 1976, a staple of Native American studies courses until the true identity of the author was revealed in 1991. Carter’s story is told in The Reconstruction of Asa Carter (2010), a fascinating documentary by Marco Ricci, Douglas Newman, and Laura Browder.

Carter was not part of the gang that assaulted Cole, but he was with them in spirit. He explained that he and his henchmen had attended the Cole concert as part of a study of the mongrel genres of “be-bop and rock and roll music.” The attack, Carter shrugged, was really no big deal. “I feel this has all been played out of proportion,” he told the Birmingham Post-Herald. “It’s nothing more than a fellow got mad and took a swing at a Negro.” The copyeditor doubtless cleaned up Carter’s actual word choice.

Yet the North Alabama White Citizens’ Council was not alone in opposing Cole’s presence on the stage in Birmingham. The NAACP and the black press also believed the Jim Crow South was no place for a black entertainer. To comply with local segregation laws by mounting separate shows for black and white audiences or placing black and white audiences in different sections of the venue, with blacks typically relegated to the balcony, only normalized the racist protocols. Performers with biracial appeal faced a tough choice: forgo lucrative Southern gigs or bow before Jim Crow.

Cole decided that, on balance, going South was better than staying away. Since black promoters had booked some of the dates and hired black staff to usher the events, Cole reasoned that if he stayed away he would be taking money out of the wrong pockets. Moreover, the shows provided top-tier talent for black audiences. “If Negro entertainers refused to play in the South, what would the Southern Negro do for entertainment?” he asked. The other option, playing only for white audiences, was out of the question, something that “would create an iron curtain against Negroes,” in effect “practicing segregation in reverse.”

Cole also believed that his dignified demeanor would advance the cause of integration. “I carry myself as a gentleman at all times hoping to win the respect of all races and to show those that would segregate that they are wrong,” he told the Pittsburgh Courier. “My conduct is to create a favorable impression of the Negro, thereby opening more opportunities to him and a better world for his children.” Of course, Cole knew he was making a devil’s bargain. When he went South, “even a performer of my standing is forced to live as a second-class citizen. I detest it!”

Cole felt that the most effective rebuke to Jim Crow was the show he headlined. Dubbed “The Record Star Parade,” it was a model of interracial cooperation and, thus, a calculated provocation. The co-stars were all white and all subordinate to the star attraction: singer June Christy; pop harmonizers the Four Freshman; comedian Gary Morton; dancer Patty Thomas; and backup musicians Ted Heath and his Famous British Orchestra, an English outfit on their first American tour. Cole hoped that the integration on stage, if not among the audiences, would be instructive. “The fact Southern audiences can see how well members of an interracial show work together will hasten the elimination of the evil [of segregation],” he said.

Birmingham certainly provided the acid test for Cole’s hopes. According to civil rights historian Ray Arseneault, author of Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Birmingham held the dubious distinction of being the most segregated major city in the Deep South. Along with Selma, Montgomery, and Anniston, its name would be imprinted as a notorious Alabama station-stop in the struggle for racial justice, the city where Martin Luther King issued his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in 1963 and where four black girls were murdered by a KKK bombing the same year. Birmingham also bequeathed to archival history the incarnation of the virulently racist Southern lawman in the figure of Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s Commissioner of Public Safety. Connor enjoyed unleashing German shepherds on and cracking the heads of peaceful civil rights protestors.

Cole and his troupe arrived in Birmingham after a successful and segregated swing through Texas. In line with Jim Crow law and custom, two shows were scheduled for the night in Birmingham: “one at 6:30 p.m. for white people, another at 9:30 p.m. for Negroes,” as the advertising specified. White tickets could be bought at E. E. Forbes Piano Company; “colored tickets” at the Temple Pharmacy. The pricing at least was equal: $2.00–$2.50 per ticket.

Around Birmingham, scores of men in the KKK and the White Citizens’ Council (dual memberships were common) lay in wait, muttering darkly about attacking the singer on stage, talking tough around gas stations and in barber shops. On the big night, however, only five assailants went inside to make good on the threats. A sixth man waited outside in a car with two .22 rifles, a blackjack, and a pair of brass knuckles.

When the men bolted across the stage, policemen, forewarned there might be trouble, rushed in from the wings and subdued them with nightsticks. The crowd of 4,000 gasped. Forgetting where they were, Ted Heath’s orchestra struck up ‘God Save the Queen’ to help quell the melee.

Responding to the pleas of the crowd, Cole returned to the stage after the attack. “I just came here to entertain you,” he said. “That is what I thought you wanted. I was born here. These folks hurt my back. I cannot continue because I have to go to a doctor.”

The crowd gave Cole a five-minute ovation. Some in the audience had tears in their eyes.

Though shaken and sore, Cole returned for the second show, the all-black show, but he backed out of the next two Southern dates on the tour. “Someone might try it again, even with 100 policemen on hand,” he said.

When the news hit the wires, a wave of indignation erupted nationwide. “The magnitude and brazenness of the incident shocks decent people throughout the land—in the North and the South,” said Billboard, which managed to find a silver lining: “By an ironic twist, the incident will ultimately accomplish some good—for it has focused national publicity on the fact that a gentleman of outstanding character and talent may not travel with freedom and safety in prejudice-ridden areas of the country.” The attack on Cole was “outrageous and inexcusable,” agreed the Birmingham Post-Herald, embarrassed that the actions of “dangerously irresponsible forces” had besmirched the city’s reputation for Southern hospitality. The paper was quick to point out that the assailants received 180 days in jail and fines, sentences that “should give the world notice that Birmingham does not tolerate that kind of despicable business.”

The black press was of two minds. Cole was praised for “maintaining a cool attitude in the wake of the Birmingham attack upon him,” but chided for being on stage there in the first place. “King Cole must remember that whenever white people have so little appreciation for other human beings that they cannot sit in an audience where there are Negroes, they are not spiritually attuned to appreciate his musical efforts,” lectured the Chicago Defender. “We hope Cole has learned a lesson.”

For his part, Cole hoped that the incident “will do a lot of good for the cause of integration. I was a guinea pig for some hoodlums who thought they could hurt me and frighten me and that would keep other Negro entertainers from the South.” He refused to hold the entire South responsible for the actions of six thugs. Singer June Christy was not as generous. “The South should be ashamed of itself,” she said. “To think that it could have happened to a genuine guy like Nat Cole. We didn’t know what to think. We were running around backstage crying.”

Cole was not a political type by temperament, but he became more outspoken and less easygoing in the wake of Birmingham. He bought a lifetime membership in the NAACP, he sued hotels that refused to accommodate him, and he blasted Madison Avenue when his pioneering NBC television variety show The Nat King Cole Show was canceled in 1957 due to the lack of a national sponsor. “They could have sold the show if they wanted to,” he said. “They sell much worse.”

But Cole continued to believe that performing under Jim Crow was the best way to fight Jim Crow. “The people, segregated or not, are still record fans,” Cole reflected in Jet magazine. “I can’t come in on a one-night stand and overpower the law. The whites come to applaud a Negro performer like the colored do. When you’ve got the respect of white and colored, you can ease a lot of things.”

Four days after Birmingham, true to his word, Cole was back on stage in Raleigh, North Carolina. He received rapturous applause from the audiences at both shows, white and black.

Cole died in 1965, by which time the Jim Crow double bills he accommodated had finally been abolished by federal law. He was only 46, his death attributable to another practice common in Cold War America: he was a three-pack-a-day smoker whom not even President John F. Kennedy, citing the Surgeon General’s upcoming report linking the addiction to lung cancer, could persuade to quit. Amid a truly national outpouring of grief at the untimely death of “the nicest guy in show business,” the black press forgot the grudges it held against Cole for not being sufficiently activist. The Chicago Defender eulogized him for advancing the civil rights cause simply by being who he was: a performer “universally respected for his superior talents as an entertainer and his superior class as a man.” In Los Angeles County, where Cole once had had to fight to move into the neighborhood, the flags were ordered to fly at half-staff.