History

The Classically Greek Roots of Civilizational Self-Doubt

The Greeks were the first of all peoples to look at themselves in the mirror.

It is because self-awareness is one of the prerequisites of oikophobia—the fear or hatred of one’s own society or civilization—that the Greeks offer us the first clear example of this phenomenon. Once they have left their mythical past behind, and scored successes against neighboring peoples, they become aware of their own power, knowledge, and uniqueness. And self-analysis requires a distancing of the self from itself, in order to view the object of study in its entirety.

One of the earliest hints of this in literature is Aeschylus’ play The Persians (472 BC), the only extant Greek tragedy based not on myth but on a historical event—and a recent one at that—namely the naval battle of Salamis eight years earlier, in which the playwright himself presumably took part. In the play, we see events from the point of view of the Other, namely the vanquished Persians, who react with shock and humanity at their lost cause. They are portrayed not as some faceless, evil horde, but as human beings with a sense of hope and tragedy. This is a remarkable achievement for a work of literature of such antiquity, especially considering the fact that it was to be presented at a dramatic competition before a judgmental audience of Athenian men, many of whom had personally fought against the Persians and had friends who had fallen in battle.

The Athenians, though their cause had been just, since they had fought for their very homes against an imperialist aggressor, understand from their benches in the theater that war victimizes also those who fight unjustly, and that the suffering of losing loved ones does not distinguish between cultures. If we are pleasantly surprised that the Athenians were this open-minded, we must be astonished at the fact that they voted to award the first prize to Aeschylus.

They have internalized, already at this early stage, the subsequent Jewish lesson that one should not rejoice at the demise of one’s enemies. In the Jewish tradition, God rebukes the angels for wanting to sing his praise as the Egyptian charioteers pursuing the Israelites are drowning in the Red Sea. To paraphrase the Talmud somewhat: The enemy soldiers, too, are human beings, and my work—why should you sing in joy, when my children are drowning in the sea?

Euripides, the third great Attic tragedian after Aeschylus and Sophocles, almost routinely questions conventional ways of thinking in his plays. For example, his in some ways sympathetic portrayal of the title character in his Medea (431 BC) raises the question of what a woman is supposed to do when suffering injustice in a patriarchal world where there is no higher authority to which she may turn for succor.

He also shatters traditional myth. In Heracles (416 BC), for instance, Euripides destroys the Greek gods, with the exception of Athena, by having them prove so evil, incapable, and spiteful, so unworthy of being worshipped, that it is only through human love and friendship, here between the kindly Theseus and the broken hero Heracles, that salvation can be found. He eventually reconstitutes the gods in a new image, through Artemis’ intervention in Iphigenia in Aulis (staged posthumously in 405 BC). In several versions of the myth, the goddess Artemis commands that Agamemnon must sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia in order to get wind in the sails of his fleet. But Euripides does not accept that a god should require an innocent human sacrifice; he instead portrays her as a benevolent force that substitutes a deer for Iphigenia on the altar in the last moment, even though the girl had heroically taken it upon herself to die for the sake of the Greek navy sailing on to Troy. So instead of making his play about the struggle between religious or political duty and personal desire, Euripides steps out of the myth and asks his audience why on earth they should believe such a thing in the first place.

Mention should also be made of the fragment from the otherwise lost play Sisyphus, by Euripides or perhaps Critias. In this surviving textual snippet, someone seemingly atheist is arguing that the gods were merely invented in order to frighten people into behaving morally. This is probably the first expression in history of this nowadays popular viewpoint. So in the development of Attic tragedy is found an increasing tendency to question traditional Greek attitudes, even to some extent Greek religion itself.

Drama aside, it is above all in the more or less historical and scientific treatises that we see what is properly a Greek self-study: Herodotus’s historical, anthropological, and sociological comparisons between the Greeks and other peoples he visited (Histories, ca. 440 BC); Thucydides’s perceptive observations not only of the Greek and Athenian character but also of human nature in general (History of the Peloponnesian War, last decade of the fifth century BC); Plato’s conservative mocking of Athenian society and democracy in the Republic (ca. 380 BC); and Aristotle’s establishment of countless scientific disciplines, perhaps most importantly, in the present context, of literary theory in his Poetics (ca. 335 BC), where he examines the literature of his own culture. The degree of self-examination in these works, and many others, has no parallel in any other civilization before the Greeks; it is the Greeks who invent theory.

Once external foes have been overcome and a measure of wealth and leisure established, intelligent men begin to focus on internal matters and to write about them. This is indeed similar to how Aristotle explains the rise of the pre-Socratics, in Metaphysics 982b: “This kind of science began to be pursued, for the purpose of leisure and pastime, when almost all necessities of life had been taken care of.”

Nonetheless, this heightened self-awareness, though often facilitating self-critique, is only a prerequisite for, and not identical with, oikophobia. Aeschylus wishes to be remembered more for his participation in the military defense of Greece than for his dramas: he is neither xenophobic nor oikophobic, and he does not set the Persians on any sort of pedestal or ascribe to their culture more than its due. Euripides’s work is full of Athenian patriotism—it is not for naught that, in the play Heracles already referred to, it is Theseus, primordial king of Athens, who rescues the son of Zeus from suicide, and only Athena herself who puts an end to the carnage—even though, in the end, Euripides abandons his native city and heads north upon the invitation of the Macedonian king Archelaus I. Although Euripides is often coupled in intellectual matters with Socrates, he thus remains pro-Athenian, even if his patriotism knows certain bounds.

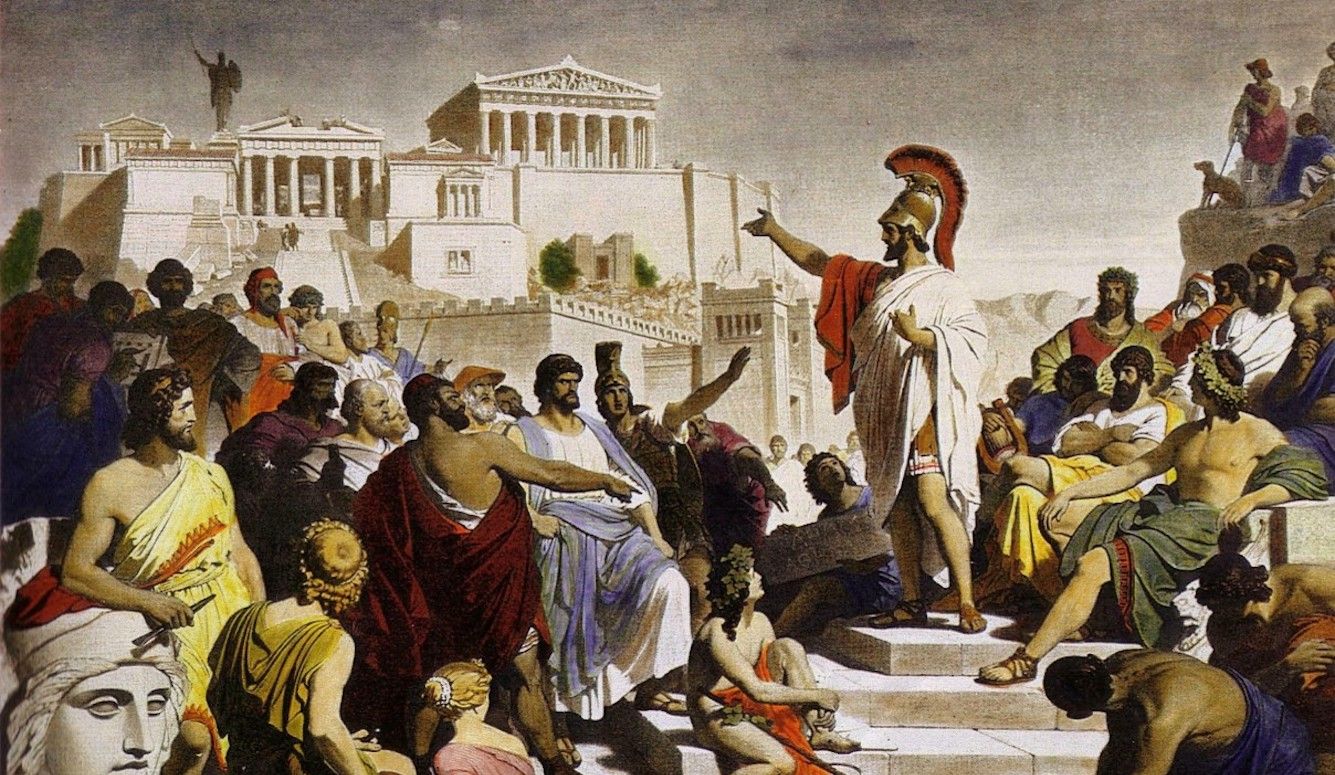

Herodotus, for his part, is happy to travel but thinks the Greek world best, especially Athens, which he seems to prefer (Histories 5.78) to his native Halicarnassus in Asia Minor, which is under tyrannical Persian sway. Thucydides has Pericles utter some of the most patriotically beautiful words imaginable on the greatness of Athens and the indomitable Athenian spirit (History of the Peloponnesian War 2.35–46). Aristotle considers it quite clear, in many different passages of his works, that his Greek compatriots are culturally superior to other peoples. So these men, and others, are able to analyze and even question their own traditions without thereby slipping into oikophobia. This self-awareness, however, which eventually becomes the natural outcropping of a cultured people, will over time have both positive and negative effects.

Hand in hand with this cultural, literary-scientific development goes the legal and political development. These two will of course in some way reflect each other in every civilization. A gradual rejection of one’s own traditions is accompanied by a fragmentation of the populace into smaller interest groups that will view the closer threat—other interest groups of the same people—as more urgent than the more distant Other. A conservative stubbornness holds a very protective and exclusive view of citizenship and political participation in the early Greek city-state (and this will be repeated among the Romans), but things gradually begin to change. The crushing naval victory at Salamis, won by poor and simple oarsmen rather than by comparatively wealthy, landed hoplites, leads the poor to demand more rights. This is why the conservative Plato views that battle in a negative light (Laws 707a–c), even though it was a Greek victory. He feels that it caused a more assertive citizenry of individuals who believe more in themselves than in the community, and he is echoed by Aristotle at Politics 1274a and 1304a. (Similarly, young Americans during the Vietnam War will successfully argue that if they can be asked to die for their country, they should be allowed to vote as well; this is a common phenomenon in history, another example being the enlistment of Russian serfs to fight in the Crimean War, contributing to the end of serfdom.)

Increasingly, the rich and the poor, the democrats and the oligarchists, come to hate each other more than either group hates the Persians. Since the common civilizational enemy has been successfully repulsed, it can no longer serve as an effective target for (and outlet of) the people’s wrath. Human psychology generally requires an adversary for the purpose of self-identification, and so a new adversary is crafted: other Greeks, and other Athenians.

An empowerment of the lower classes through this postwar democratization in Athens also leads to an increasing culture of dependence on the government. As the voices of regular people start to count more and more, the democratic leader Pericles and his aristocratic opponent Cimon begin to compete with each other by essentially bribing Athenian citizens voting in the Ecclesia, the Athenian Assembly. After the ostracism of his rival, Pericles’s dominance in Athens (ca. 461–429) involves ever more largesse for the purpose of maintaining support from the politically strengthened populace. As governmental largesse often does, Pericles’s generosity makes men ask what more they can get from the government, and makes them less willing to sacrifice themselves for the state.

Late in the fifth century BC, payment to the participants in the Ecclesia is introduced, so that even the poorest citizens can afford to take off from work and partake in government there. One can look upon such a policy as equitable and fair—just as one may entirely agree with the brave trireme oarsmen at Salamis—while at the same time recognizing that it furthers the mentality of avarice, as well as the attitude that the state is simply there for one’s own direct personal benefit and gain. For it should be considered an axiom of human nature that dependence leads not to gratitude but to resentment—already Thucydides knows this—and when the state provides goods at no charge, or even cash handouts, the people come to consider themselves entitled to it and develop the mentality that asks not what service one can provide to others, but how much one can get from others, primarily the state.

In short, dependence makes people resentful and miserly, and the more they receive from the state, the less they will respect it. This is why there is often a dynamic of mutual strengthening between oikophobia and government largesse, and oikophobia and the entitlement mentality go hand in hand.

Elements of this can be seen in Thucydides (1.77), where some Athenian diplomats explain to their Spartan hosts that subjects of the Athenian empire are more resentful precisely because of Athenian generosity than they would have been if the Athenians had treated them with brutal force from the start. Another example (3.37–39) is where Cleon of Athens, in the famous debate on the fate of the rebellious Mytilenians, argues that showing kindness and mercy will not make the Athenians more liked, and that it is a general rule of human nature that people all too often despise those who treat them well and admire those who are firm. This will be echoed by the Roman commander Vocula in Tacitus’s Histories (4.57).

Once this sense of entitlement becomes the predominant outlook, the citizens of a state begin to compete more with each other, while the external enemy recedes into the background. Over time, it is forgotten why the enemy, soundly defeated, was ever an enemy, and he seems harmless, even benevolent, in comparison to the ruffians at home who are competing for money and prestige. Oikophobia has begun.

The oikophobic element of these late Classical times comes creeping in well after the xenophobic phase that commences upon contact with the Other, and overlaps more with the middle, self-aware but not yet self-denigrating phase. And this pattern will generally obtain for other civilizations, too. The first very clear trace of oikophobia appears in the later Classical era, namely in the time of Socrates and his entourage. Socrates is not, as Nietzsche would have it in The Birth of Tragedy, so much the conspiring destroyer of Greece as part of a natural process of self-destruction that cultures in general go through, a process in which Socrates has more than enough accomplices. To understand the Greeks—and with them, everyone else—we must follow them all the way to the end, something that Nietzsche is unwilling to do.

Nietzsche considers the Archaic Greeks (c. 800- 479 BCE) the greatest expression of Greekdom—that is, the Greeks who were more secluded from the Other and thought themselves the best simply because they entertained no other possibility, who were naïvely closed to any other way of thinking, and who believed in their own myths—in short, Greeks as Homer portrays them. To be sure, there is much we might learn from those Greeks and from their naïveté. But Greekdom does not stop with the Archaic Greeks; it continues into Classical times, to Socrates, and beyond.

The Greeks were the first of all peoples to look at themselves in the mirror, the first people who wrote about what they did and who knew that they knew. Whereas someone like the sixth-century-BC poet Theognis would have considered the Greeks to be the best simply because no other possibility was even conceivable, the fourth-century-BC Aristotle considered the Greeks to be the best because he had compared the customs and mores of various peoples and concluded that the Greeks were indeed superior. It was this latter posture that enabled them to be the first self-critical people, and that is a remarkable achievement, one that is almost entirely absent from Nietzsche’s appreciation of them, and that he rejects as un-Greek.

Nietzsche’s understanding of the Greeks is of a piece with his insistence that the “master” individual has such a distance from others that he, practically unaware of them and hence of other possibilities, legislates his morals without the self-consciousness that awareness of others entails. He believes that a people, to be great, must be naïve, must believe its own myths. To him, once a people becomes aware of its own history, it will become sick and enfeebled.

There is much truth in this, but we must also understand that, first, this process is inevitable, and, second, until such a sickened state is reached, much good will have been accomplished along the way. Nietzsche does not understand, or refuses to acknowledge, that also the declining period of a people can produce some of its great cultural achievements. The rise itself contributes to the fall, and what was strength, namely diversity and openness in adopting new ideas, becomes weakness and fragmentation.

Excerpted, with permission, from Western Self-Contempt: Oikophobia in the Decline of Civilizations, by Benedict Beckeld, published by Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2022 by Cornell University.