Mobbing

Confessions of a Social-Justice Meme Maker

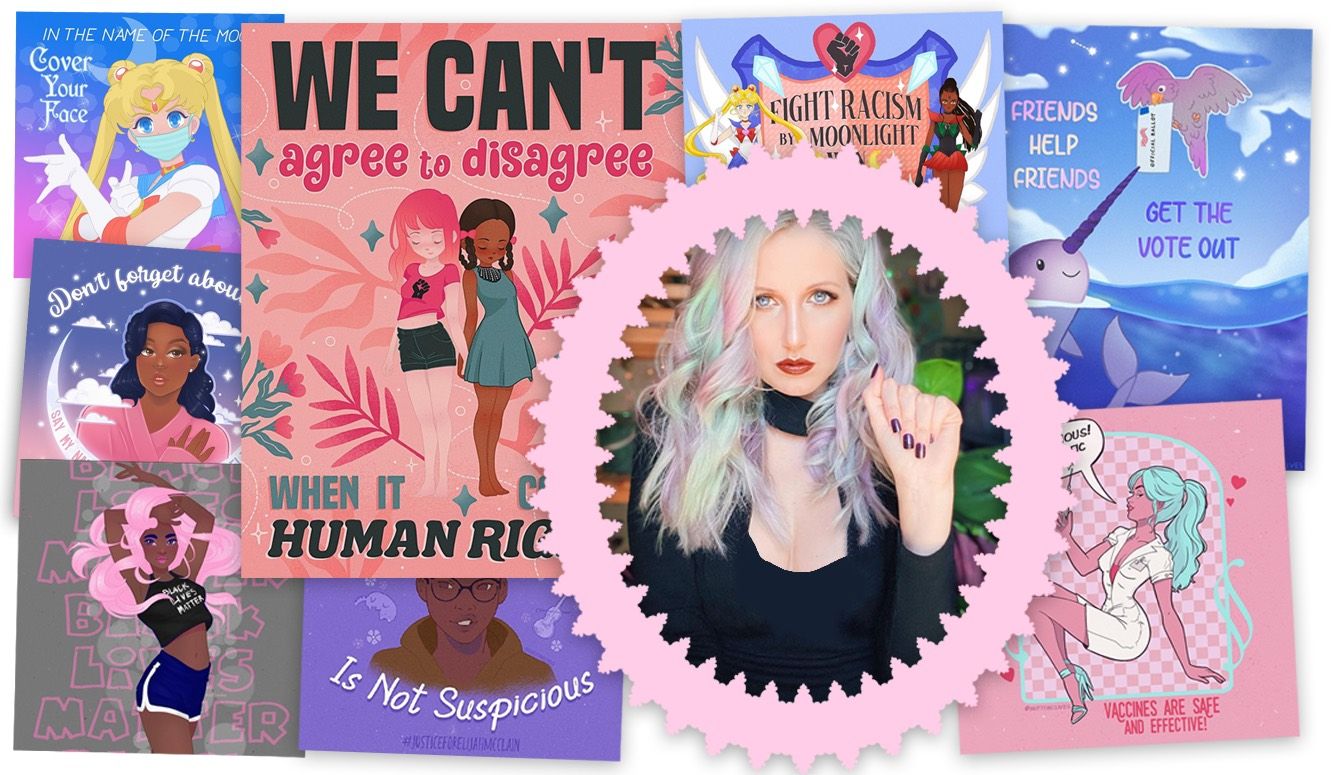

I made pretty pictures that helped keep people enraged and mobilized. Then I asked myself: ‘Why am I doing this?‘

When the pandemic struck in March 2020, I was working out of a Los Angeles apartment alongside my two cats, illustrating children’s books for a living. Much of my life played out online, where I carefully counted the number of “likes” my social-media posts would get, imagining this to be a reliable indicator of my ideas’ worth. As an artist, a growing social-media following also helped me find new professional opportunities, as well as customers for products I sold on Etsy.

During lockdowns, my reliance on social media became more pronounced, with Instagram as my platform of choice. I began to think of myself as an “influencer.” That word now has negative (or at least mixed) connotations. But for those who are introverted or neurodivergent, and who have difficulty navigating real-life social settings, the prospect of making an impact through arms-length electronic methods held considerable appeal. (I have Asperger’s syndrome, a subject I have written about publicly in the past.)

Eventually, I gravitated toward the social-justice art community. At a time when the world was experiencing a sense of collective fear over COVID-19, it was nice to imagine that my art was giving people joy and comfort. And of course, when these people were moved to share my art with others, well, that aligned nicely with my goal of attracting new followers. But I assured myself this was not the main purpose.

By the time the Black Lives Matter protests and riots began in mid-2020, I was fully immersed in this subculture. And the cute, non-threatening social-justice-themed images that I’d been producing gave way to a harder activist message. At the time, infographics educating people about anti-racism were flooding Instagram, stripping complex social issues down to ideologically slanted but easily digestible bullet points. Text-based slideshow graphics on pastel backdrops were a particular hit. They often read like instruction manuals, feeding believers the exact phrases needed to dismiss counterarguments and “educate” their “ignorant” family members.

Knowing a popular craze when it sees one, corporate America incorporated these facile social-justice memes into national marketing campaigns. Disavowing racism had become a brand imperative, with influencers and businesses alike at risk of reputational damage if they failed to jump on the bandwagon early and hard. Along with the infographics, there was an explosion in the market for illustrative typography featuring simple slogans such as Angela Davis’s “It’s not enough to not be racist. You must be anti-racist.” Silence was violence. And so on.

I accepted the underlying ideology of anti-racism without question. Publications such as the New York Times and Washington Post assured me that I was on the right side of history. The online community I belonged to was effectively an echo chamber, in which ideologically non-compliant facts and statistics could be explained away with the help of all those aesthetically pleasing images. If so many earnest people of all races insisted America was experiencing a racism “pandemic,” who was I, a 31-year-old white woman, to say otherwise?

In the standard California fashion, I’d been a registered Democrat from the time I turned 18, and voted accordingly in every presidential election. But that was the extent of my involvement (and interest) in mainstream politics. I’d considered myself moderate in my attitudes, having avoided the excesses of such previous left-wing bandwagons as #MeToo. Even the first three years of Donald Trump’s presidency didn’t stir the same sense of anger in me that I observed in other Democrats.

But when COVID struck, my news consumption spiked—primarily CNN and MSNBC, which placed much of the blame for the pandemic, not to mention America’s racial inequities, on Trump. I developed the sense that we were living through a crisis that required each of us to make an existential choice. On one side lay those who wanted to make the world a better place. On the other lay the bigots and anti-vaxxers. Conveniently, it was the same line that separated my country into Democrats and Republicans.

My social-media output attracted the attention of a popular progressive Instagram account then called @WeFuckingHateDonaldTrump, which began regularly “pinning” my witty comments to its own posts. The account had garnered more than 700,000 followers in just four years, with the bulk of the content consisting of memes bashing Trump and his supporters, along with other polarizing progressive clickbait.

I befriended the account’s owners, a couple from Australia, and eventually joined their team as a content creator and curator. In lieu of being paid, I was allowed to use the account to direct followers to my personal Instagram page. In the online world, this kind of access to a large audience is a valuable asset, and so the arrangement made sense to me. (My bosses, I later learned, were hoping to hit the million-follower mark so they could comfortably quit their day jobs. They also would go on to create a loosely associated lifestyle clothing brand that’s now promoted on their page.)

Because of the time differences at play, my Australian bosses needed help posting content when their target viewers—angry American progressives—were online. I shared the morning time slot with Frederick Joseph, a New York-based author and avowed anti-racist who would later become famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) for reasons described below. By the time we were working together, he’d developed a substantial following largely thanks to his tweets about “white women,” “whiteness,” “white tears,” and “white supremacy.”

White supremacy built America and if given the opportunity, white supremacy will destroy it.

— Frederick "Pre-order Patriarchy Blues" Joseph (@FredTJoseph) January 13, 2021

With my instructions being to increase our follower count, I dutifully studied Instagram’s “Insights” feature (accessible to “creator” accounts), to learn which posts reaped the highest engagement. I quickly learned that the key to reaching legions of viewers is to post content that evokes strong emotional responses. In a saturated market, extreme views drive out more nuanced takes.

The narrative we sold to the masses in late 2020 was that “white supremacy” was the greatest threat that America was facing, and that Republicans were the “party of white supremacy.” At the time, I believed this wholeheartedly. When a beloved cousin died from COVID, I became even more strident, making Trump a scapegoat for my anguish. And there I was, at the controls of an Instagram propaganda machine that reached hundreds of thousands of similarly pissed off people.

Once we’d tapped into an emotionally satisfying narrative about the problem that America was facing, it was easy to demonize the people standing in the way of progress. But this rhetoric came with an awkward catch: In outward appearance at least, I was arguably part of the problem we were constantly ranting about—since I am a straight white female who was “centering” myself in a social-justice struggle that (as we’ve all been told) must be led by marginalized people.

Things got more complicated in January 2021, when Joe Biden was sworn in as president. How do you sustain an account called @WeFuckingHateDonaldTrump when Trump is no longer in the White House? It had been my job to keep people enraged and mobilized so that we, Team Blue, could enact social change by getting rid of the bad guy. And that battle had been won.

However, the owners didn’t seem to have any new business plan that didn’t involve the output of more outrage porn. And it was at about this time that I wondered why I was trying so hard to keep ramping up the vitriol. I also began wondering how my output was affecting the lives of those who viewed it. I stopped reducing people to numbers on an “Insights” page, and started trying to think of them as individuals.

Without Trump to kick around, progressives were increasingly turning on one another. Left-wing activists dedicated more and more of their time to scouring the online social-justice community, looking for opportunities to take offense. The melodramas that ensued attracted a lot of attention, allowing (victorious) combatants to level up their bona fides and follower counts.

My turn came when an activist influencer named Keiajah “KJ” Brooks called me out in the comment section of a post, after I’d made a dig at controversial right-wing pundit Candace Owens, who happens to be black. According to KJ, my white skin disqualified me from such commentary. Fred Joseph, my aforementioned coworker, joined in the pile-on.

The next day, Joseph doubled down, posting a video explaining why it was racist for white people to criticize black people for any reason. When I brought this up to our bosses, they said that they’d let a black person decide what is racist. It seemed strange to me that one would surrender his or her critical faculties for the sake of doctrinal purity. But then it dawned on me that I was being a hypocrite, as this was exactly what I’d been doing.

I’d never really listened to a word Owens or any of the Republicans I smeared ever said—at least, not in good faith. I was just looking for an opening to mock them. I postured passionately in support of arguments and issues that I knew little about. I didn’t give anyone the benefit of the doubt if they disagreed with me. I realized I needed to take a step back and re-evaluate what I was doing with my life, and so quit working for @WeFuckingHateDonaldTrump (which now calls itself The Progressivists) in February 2021.

Since that time, my former employer has pivoted to pushing an anti-capitalist agenda, notwithstanding the fact that the owners seem to share the same professional motivation as most of the people whom the site criticizes—i.e., making money. Joseph, meanwhile, is now best known as the guy who got a woman fired from her job at a community-events software platform after she’d made agitated comments to him at a local dog park—after which, Joseph himself was called out for his own call-out by none other than 1619 Project creator Nikole Hannah-Jones, an alpha player within the social-justice milieu.

In the aftermath, I was left with 32,000 personal Instagram followers. It wasn’t a bad tally, but almost all of these people were militant leftists whose beliefs I no longer shared. And there was simply no way I could keep these followers happy while staying true to my beliefs. (Having Asperger’s makes it difficult to be inauthentic.) So I watched the audience I’d worked to build drop by the hundreds every time I’d post such controversial statements as “We shouldn’t cancel each other,” “Republicans are not all racists,” and “there are only two sexes.” As a result, I now get messages calling me a white supremacist and a Nazi, along with violent threats. All of this only serves to confirm my suspicions about the hypocrisy that lies at the heart of online social-justice culture.

I now look at the world around me, America in particular, in a new way. The United States of 2022 is a far less racist and intolerant place than it once was. Yet the denunciations of it that one hears from progressives have become steadily more apocalyptic. Activists need a struggle to overcome, a dragon to slay, even if it must be invented. And when there are no dragons to fight, they fight each other. This isn’t a recipe for societal improvement, much less for personal happiness.

I started fresh, with a new Instagram account called the Politically Homeless Shelter (@PHShelter), for those who don’t feel at home in either political camp; and have a new Etsy store that caters to people with “problematic” views (which, naturally, has already been disabled twice for promoting “hate speech”). On Instagram, I’ve experienced shadowbanning, had posts removed for arbitrary reasons, and had my account temporarily disabled. It’s been discouraging, but I continue to amplify information that I regard as important, in my small way. And yes, I still make a point of promoting my brand—as I’m unabashedly doing here. But hey, a woman’s got to eat.

Seeing how the Democrats rushed to embed dogmatic formulations of social justice into their platform, I can no longer in good conscience align myself with their party. But neither do I align myself with Republicans, who, in many states, are now rolling back abortion rights (though even on this issue, I am not nearly so dogmatic as I once was). I’m now registered as an Independent, and consider my vote up for grabs.

My advice to others is this: Be wary of simple explanations, black-and-white thinking, and any ideology that presents the world as locked in a battle between good and evil. Take it from someone who once channeled this kind of simplistic thinking into popular memes for a living: Everything worth knowing is much more complex than any slogan can possibly convey.