Politics

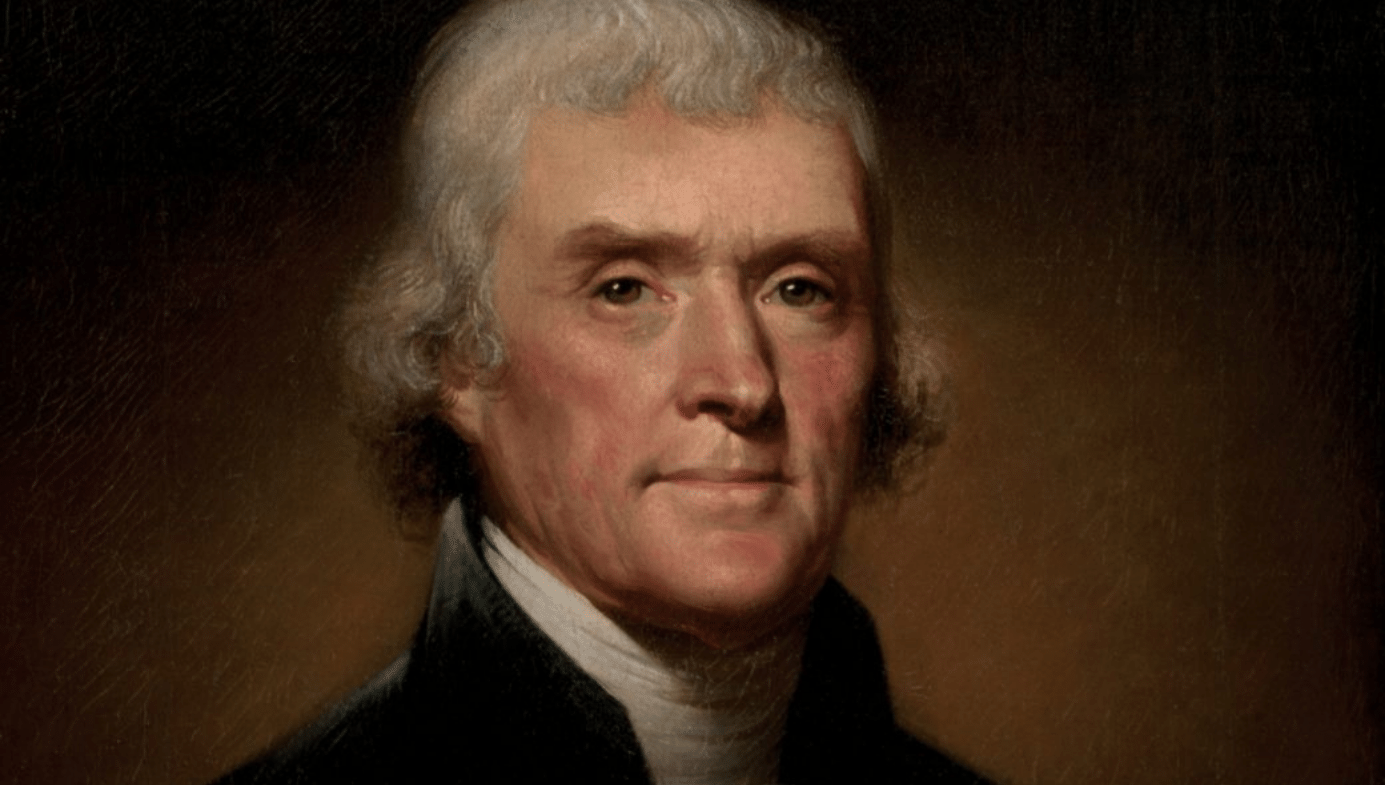

What a Free Republic Owes Thomas Jefferson

Late in his life, John Adams sent a letter to his great political rival Thomas Jefferson in which he wrote, “You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other.” Adams must have understood Jefferson by the end, because on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, he died with his old friend’s name on his lips: “Thomas Jefferson still lives.”

In fact, Adams outlived Jefferson by a few hours, but the latter’s abiding influence in America, even at this distance, has been so pronounced that it somehow justifies the claim anyway. Not everyone is happy about this. A statue of Thomas Jefferson has just been removed from City Hall in New York City, where it stood for 187 years. The decision—by unanimous vote—was the work of the city’s Public Design Commission, which deemed the Virginia statesman unfit for public veneration on account of his ownership of human property.

The commission’s decision has been defended by distressed members of the City Council. “Thomas Jefferson was a slaveholder who owned over 600 human beings,” declared Council member Adrienne Adams, co-chair of the Black, Latino, and Asian Caucus, in a presentation last month. “It makes me deeply uncomfortable knowing that we sit in the presence of a statue that pays homage to a slaveholder who fundamentally believed that people who look like me were inherently inferior, lacked intelligence, and were not worthy of freedom or right.”

In point of fact, Adams is hopelessly mistaken about our third president—further proof, if any were needed, that American civic education is in crisis. Jefferson was certainly a slaveholder animated by the common sentiments of his age regarding discrepant human races. It needs to be remembered, however, that Jefferson was scarcely an opponent of natural rights. To the contrary, as a disciple of Enlightenment philosopher John Locke, Jefferson was one of history’s leading expositors of natural rights theory.

And, of course, Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, the preamble to which, as Christopher Hitchens put it in his slender biography of the Virginian, “established the concept of human rights, for the first time in history, as the basis for a republic.” This charter of freedom, as Jefferson was careful to insist, captured the broadly shared “common sense of the subject” in the American colonies, the subject being “our rights.” But even if Jefferson meant the Declaration to be an “expression of the American mind,” it required uncommon words to give the first modern nation’s Enlightenment precepts world-historical resonance.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” With these imperishable words, Jefferson ensured that a revolutionary “instrument” would be far more than an object of merely national import. This universal emphasis was natural and proper from a man who had, according to Henry Adams, “aspired beyond the ambition of a nationality, and embraced in his view the whole future of man.” Despite his deplorable personal failure to escape the shadow and stain of chattel slavery, Jefferson always exhibited a strong preoccupation with the rights of man evident in his most famous work.

The affirmation of human equality in 1776 was addressed not simply to the British crown or the parliament or even to other Americans, but to “a candid world.” It presented an enlarged conception of natural rights applicable to all men at all times. It has proved the “sheet anchor of American republicanism,” as Abraham Lincoln called it. Put differently, it has provided what America's final founder, Martin Luther King Jr., called a “promissory note” to all Americans. And yet, it also contained the germ of universal liberty that Jefferson hoped might spread to every nation. “May it be to the world what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains … and to assume the blessings and security of self-government.” In any of this, where exactly does one find a belief that some people are “not worthy” of equal natural rights?

For New York City to remove Jefferson’s statue is a travesty that follows the dreadful path of the New York Times’ “1619 Project.” Placing themselves in the ranks of the historically obtuse who insist that America is a racist republic founded on a lie—incidentally, white supremacists have long held views that are not dissimilar—the city council has shown itself suspicious of and hostile to the precepts and symbols that have defined and distinguished the country since its birth. What’s more, the city council has heaped contempt on notions that have stirred American reformers for centuries in their commitment to remedy America’s grossest wrongs and crimes. From the Seneca Falls conference on the rights of women to the Civil Rights campaign, “the magnificent words” of the Declaration (to borrow Martin Luther King’s description) have fortified the march toward a more perfect union. Nor have they been the exclusive property of the American people, inspiring freedom fighters and dissidents from behind the Berlin Wall to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

The indiscriminate and frenzied impulse to haul down statues in contemporary America is suggestive. It bespeaks a demand for moral purity from our ancestors—or ourselves, even—before the erection of statues and memorials, but this would be to ask too much of human virtue. In their own time, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Martin Luther King recognized that the standards of self-government did not require humans to be angels. That would be to make the perfect the enemy of the good. Their arduous struggles would permit admiration of deeply flawed men and women, but not men and women without great virtues or incapable of noble deeds. Those citizens who aspired to virtue and fell short in their personal lives could make precious contributions to the national character if they aspired to greatness in their public lives.

This concentrated wisdom of generations evidently escapes the New York City Council. Bored with the Enlightenment and imagining history to be little more than a morality tale, the spoiled enemies of Jefferson are ranged against the American creed itself. They fail to understand that Jefferson’s ideas can remain valuable, independent of the character defects of their author—Jefferson can be honored for his incomparable service to human liberty despite his execrable involvement in the slave trade.

A sober and mature reading of history is required to preserve the best of the past, and ensure that it survives in the future. This used to be tolerably well understood by citizens of all stripes and stations, not least among the governing class. In establishing the Jefferson Memorial at the height of World War Two, President Franklin Roosevelt declared that Jefferson was an “apostle of freedom.” This was not a theoretical position conceived to burnish his reputation without the risk of sacrifice. Jefferson and the other patriots of 1776, Roosevelt said, “lived in a world in which freedom of conscience and freedom of mind were battles still to be fought through—not principles already accepted of all men.”

The Declaration of Independence, lest we forget, was also a declaration of war. The boldness of this decision, by pen and sword, is difficult for us to comprehend in retrospect. The last line of the Declaration of Independence ought to be better known: “we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” This was not simply a rhetorical flourish. The defeat of the 13 colonies would have seen the 56 signers of the Declaration and the other leaders of the American Revolutionary War swing from the gallows. As Benjamin Rush said, his fellow signers knew they were signing their own “death warrants.” It involves no exaggeration to say that if Jefferson and the rest hadn’t found such reserves of courage, their convictions would have been for naught.

Roosevelt also recognized something else that the New York City Council does not: those convictions changed the course of history. Before Jefferson, the idea that a democratic republic was a just form of government remained heavily contested, and not only in monarchical Europe. (John Adams assailed “democratical” government when he sought to inveigh against mob rule.) After Jefferson, it became assumed by many in America and beyond that government arose from the consent of the people, and was neither a gift to them nor an imposition. And so, “Thomas Jefferson believed, as we believe, in man,” said Roosevelt. “He believed, as we believe, in certain unalienable rights. He, as we, saw those principles and freedoms challenged. He fought for them, as we fight for them.”

In an even darker hour in the life of the republic, on the eve of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln noted a disheartening irony that should give all Democrats today pause. The name of Jefferson had lost much of its prestige since the days of the revolution, especially in the political party he had founded (with the help of James Madison). “It is both curious and interesting,” Lincoln observed, “that those supposed to descend politically [from Jefferson] have nearly ceased to breathe his name. It is now no child’s play to save the principles of Jefferson from total overthrow in this nation.” And if the principles of free government wouldn’t be saved by “those claiming political descent from him,” the task would fall to those “from the party opposed to Jefferson.”

Lincoln understood that the mission of the newly founded Republican Party would be to uphold the Enlightenment principles that Jefferson had committed to parchment. Lincoln knew that Jefferson betrayed these principles in his capitulation to a slave power that he at once feared and loathed. Lincoln also knew that Jefferson was heavily invested in the practice of involuntary servitude, and had taken his slave Sally Hemings as a mistress. Lincoln’s confidante William Herndon explained Lincoln’s paradoxical thoughts about Jefferson: “Mr. Lincoln hated Thomas Jefferson as a man—rather as a politician, and yet the highest compliment I ever heard or read of his was paid to the memory of Jefferson.”

At the end of his life, Jefferson cited the Declaration as his greatest contribution to the world—it was the first of three achievements listed on his tombstone that he most wished to be remembered for. It was precisely on this ground—the principles of human emancipation and equality—that struck Lincoln as worthy of Americans’ familiarity and reverence. “All honor to Jefferson,” he proclaimed in 1859. For it was he “who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.”

In common with a great many other patriots and lovers of liberty, Lincoln appreciated the unique moral force of the Declaration—the self-evident truths of which were “the definitions and axioms of a free society”—and couldn’t resist paying homage to its author, a man of truly revolutionary and democratic temperament. For those who wish to save the principles of Jefferson from total overthrow, a small but significant task is to keep Jefferson on his pedestal.