Art and Culture

Cancelling the Beat Generation

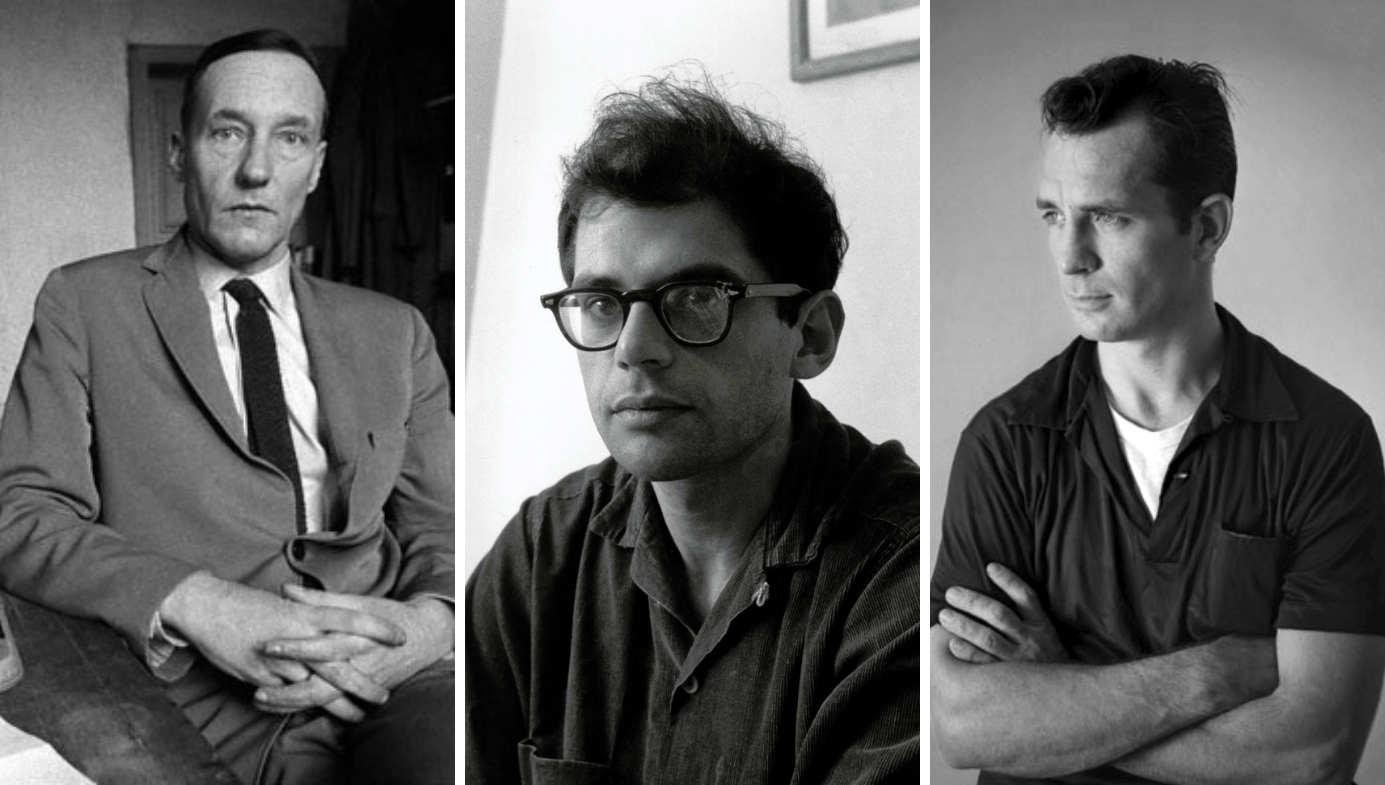

Almost from its inception, the Beat Generation seemed to be doomed to failure. In and around Columbia University, a ragtag group of bohemians coalesced based upon an odd array of mutual interests. Two of them were homosexuals, one bisexual, and all were interested in drugs and subversive literature. William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Lucian Carr were fascinated by the underground culture of criminals and hustlers, hobos and vagabonds. It was the mid-1940s and they had no interest in middle-class values. They were more interested in experience, in expanding their minds through drug use, and in forging a new philosophy called “The New Vision.”

It is perhaps fitting that the “libertine circle,” as it was known, was blown apart by a murder. Lucian Carr, likely pushed to breaking point by the sexual advances of Burroughs’s friend David Kammerer, stabbed the older man to death in a park and hid his body in the Hudson River. Kerouac was jailed for helping Carr dispose of the murder weapon, Burroughs was forced to start a new life in Texas, and Ginsberg was left alone in New York, where soon he would be locked up in a mental institution. For Carr, it was the end of his youthful experimentation, but the friends would continue to correspond, and Burroughs, Kerouac, and Ginsberg would go on to become some of the most important writers of their era, shaping not just American literature but the whole culture with their radical approaches to art.

In the 1950s, as post-War America settled into an era of unrivalled prosperity, the Beat Generation—named by Kerouac in 1948—grew infamous for its rejection of conformity. To suburban housewives, fusty literary critics, and especially to police officers across the United States, the Beats were more than merely a curiosity—they were abhorrent, un-American, and dangerous. Even before they became a household name with “Howl” and On the Road in 1956 and ’57, respectively, they had already achieved a modicum of notoriety. Kerouac’s first novel had briefly touched upon their lives, while John Clellon Holmes’s Go and early Beat works like George Mandel’s Flee the Angry Strangers and Chandler Brossard’s Who Walk in Darkness explored the lives of these new bohemians in more detail. It was an era in which the placid surface of Americana was easily disturbed.

In the early '50s, they were viewed as fringe characters on the very furthest peripheries of society, but as the decade wound on, the Beats came uncomfortably close to influencing social norms. While Burroughs fled the US in search of more liberal enclaves, Kerouac and Ginsberg headed out west, and as they did, the Beat circle grew, overlapping with other literary and cultural movements. In San Francisco, a poetry scene emerged that found its feet at the Six Gallery on October 7th, 1955, with the first public reading of Ginsberg’s “Howl,” published in book form the following year. Then, in 1957, Kerouac’s On the Road was released and the Beat Generation was suddenly a household name. Newspapers and magazines sought to explain the inexplicable, translating hep talk and speculating on what would make otherwise normal young men want to wear dirty clothes and litter their speech with profanity.

The backlash was almost immediate. After the publication of Howl and Other Poems, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and his City Lights publishing operation were taken to court and charged with obscenity. It was a bitterly contested court case, but ultimately the publisher won as Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that the book was not obscene due to “redeeming social importance.” Remarking on Ginsberg’s use of graphic language, he wrote: “An author should be real in treating his subject and be allowed to express his thoughts and ideas in his own words.” The triumph of the defendants paved the way for previously banned books like Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer to be published in the US, but also helped publicise the nascent Beat movement.

Legal challenges turned into general criticism as the Beats became infamous. Though there had been some scattered criticism before On the Road, there really hadn’t been much to criticise. The Beats were just an obscure group of friends making insignificant art—and few would have acknowledged that “art” was even the right term for free-form poetry. Yet, as soon as they were worth attacking, they found themselves assaulted from all angles. A writer for the Chicago Tribune told readers that the Beats “create worthless literary dissonance” and that “they are cheapening literature.” Herb Caen famously coined the word “beatnik” to connect these countercultural oddities with the Soviet threat. It was a pejorative term that conflated the avant-garde artists of the Beat Generation with the fauxhemian hangers-on who inevitably followed, and six decades later the epithet remains effective, as few can distinguish between the two groups.

The insinuation that the Beats were communist was hardly surprising. On the Right, there was no shortage of fear that “the Reds” would try to subvert American social norms as part of a worldwide communist plot, and artistic and left-leaning people were most likely to attract suspicion. Though few on the mainstream Left felt any kinship with the Beat writers, to the right-wing they were about as far-Left as politics could get. This would have irked Burroughs and Kerouac, who were very definitely not liberals, though Ginsberg, who certainly was, had some communist sympathies until his illuminating travels behind the Iron Curtain in the mid-'60s.

While Kerouac and Ginsberg were publishing their most famous works, William S. Burroughs was in Tangiers, working on his own twisted masterpiece, Naked Lunch. In 1958, parts of the novel were published in the Chicago Review, to the horror of the university administration. The magazine had previously been student-run, but the backlash to Burroughs’s writing was so severe that the university announced the following edition would be subject to censorship. Every editor but one resigned in protest. Those who had quit, including poet Paul Carroll, founded a new publication, BIG TABLE, which ran further excerpts from Naked Lunch. The battle with censorship, however, was just beginning, and the renegade editors were charged with mailing obscene material when their magazine was published.

The novel was finally released in France in 1959, and by 1962 it was banned in Boston after yet another obscenity trial. The decision was only overruled in 1966, when testimony from Ginsberg and Norman Mailer helped convince the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court that Burroughs’s novel also had redeeming social value. This ended one of the last American obscenity trials and, over the years, the Beats came to be viewed more favourably, particularly in left-leaning segments of society. As so often happens, the establishment that once ostracised them began to accept them. First came biographers and scholars open to new subjects and ideas—people like Ann Charters and John Tytell paved the way, exploring Beat art and biography with the respect and consideration it deserved, and later a generation of educators who came of age in the '50s and '60s pushed to have the core Beat texts included in their curricula. Ginsberg himself worked with various institutions to legitimise Beat writing and brought many of his friends into the classroom to lecture on literature.

As Beat writing found its way into college courses and volumes of important literature, translated and published all around the world, it did not shy away from controversy. Though new groups, like the hippies and the punks, came to take flak, Beat literature still faced challenges. Allen Ginsberg, the most outspoken of the Beat figures, sometimes seemed determined to recapture that old infamy, continually pushing boundaries, getting arrested, and challenging expectations. He had bested his regressive counterparts and survived the turbulent '50s and '60s to become a venerated figure by the '70s. Even under the Reagan administration and America’s embrace of conservatism during that era, he was nearly untouchable. His views were unpalatable to many, but he represented that most American of rights—free speech.

In the late '80s, however, Ginsberg joined the National Man/Boy Love Association, a group for paedophiles and pederasts. He spoke openly in their defence and was filmed at one of their events. To Ginsberg, it was just one more free speech issue, but not many others saw it that way. His assistant, Bob Rosenthal, remonstrated with him, but Ginsberg replied, “You know I think I finally found a cause that is completely indefensible!” There is no evidence to suggest that Ginsberg was a paedophile himself, but unfortunately the NAMBLA incident was hard for anyone to defend. In his memoir, Straight Around Allen, Rosenthal explains that Ginsberg’s odd stance on this issue put an end to his ever-increasing status as the great American poet, denying him the opportunity to become a professor at Columbia or be named poet laureate, and suddenly put him on the outs with major media outlets like the New York Times.

After his death in 1997, Ginsberg remained a controversial figure, as did the other Beat writers. Even in the 21st century, their confessional prose and poetry, which frequently dealt with drug use and homosexuality, can be too much for some. In 2015, an experienced, award-winning teacher was forced to resign after failing to allow his students, who were in an advanced college prep class, to “opt out” of listening to Ginsberg’s “Please Master,” a particularly explicit poem about Neal Cassady. The school claimed that hearing the poem had “put the emotional health of some students at risk.”

While it is not wholly surprising that pornographic poetry remains controversial, especially in the classroom, what is extraordinary is the way in which the assaults on the Beat legacy have now switched from the Right to the Left. Although their well-documented and valiant efforts in fighting obscenity, challenging corruption, calling for environmental awareness, and—perhaps most notably—pushing for gay acceptance have made them heroes to many, they are now problematic, to use that most familiar of expressions.

For more than a decade, it has been de rigueur to criticise the Beat writers, not because of their progressivism, but for a perceived lack of it. It is easy to pitch an article or essay complaining about Kerouac’s sexism. Even in explorations or celebrations of their work, their white privilege and misogyny is routinely denounced. But attacking artists from history for their lack of 21st century values is tiresome. It is exhausting reading these dull tracts. From Jezebel to the Guardian and Salon, left-leaning publications are turning against the very writers who helped make possible the freedoms and attitudes they now take for granted. In academia, we must now expand the Beat canon to include tangentially related artists—even those who denounced the word “Beat” or were of another generation entirely. It is easier to defend Amiri Baraka—a man who called for the extermination of Jews and abandoned his children because of the colour of their skin—because, as a black poet, Baraka is considered an acceptable inclusion in modern curricula.

This is not to suggest that there is nothing within the lives and work of the Beat writers to criticise—there most certainly is. And indeed the work of related artists from that era, including women and people of colour, does deserve more attention. However, amid the interminable culture wars, it seems the inclusion of core Beat writers on college syllabi is increasingly tenuous, in spite of their towering cultural contributions. In the recently published The Beats: A Teaching Companion, there are several depressing anecdotes about the difficulties of teaching Beat literature over the past few years. Professors who have taught On the Road for decades are struggling to justify its inclusion on literature courses because it was written by a white male cisgender author. It is no longer just university administrators who are pushing back against the Beats; it is the students, too. This book, so important in the lives of young people over the six decades since its publication, has finally met a generation immune to its charms.

These students are the benefactors of decades of forward progress made possible by the efforts of the Beat writers. Their views on race, gender, and sexuality exist today in part thanks to the art and activism of the Beats. Whilst Kerouac was definitely not a hippie, his literature was a tremendous influence on the '60s counterculture and it was this movement that set the ball rolling for decades of social change. Burroughs similarly influenced the New York punks, who pushed transgressive attitudes, opening yet new avenues of tolerance. Ginsberg was America’s most outspoken activist from the '60s through to his death in 1997, helping to shape a culture of protest that made possible immense social changes. The Beats were products of their time, yet their progressive attitudes towards race helped their fellow white Americans become more inclusive, and their push towards sexual liberation and gay rights was monumental in shifting attitudes to the point that the prevailing values of their era now seem startlingly archaic.

The Beat authors were no saints and healthy criticism is vital, but the left-wing reactionaries attempting to remove them from the curricula are as ignorant as their right-wing counterparts who attempted to keep them out more than a half-century ago. Perhaps today’s progressives could learn something from the conservatives they emulate, who were forced to acknowledge that literature they could not understand was at least allowed to exist due to its possession of “redeeming social value.” They may be uncomfortable with the gender and skin tone of those great writers, but they should not deny that their literature has a place in the pantheon of modern American writing.