Art and Culture

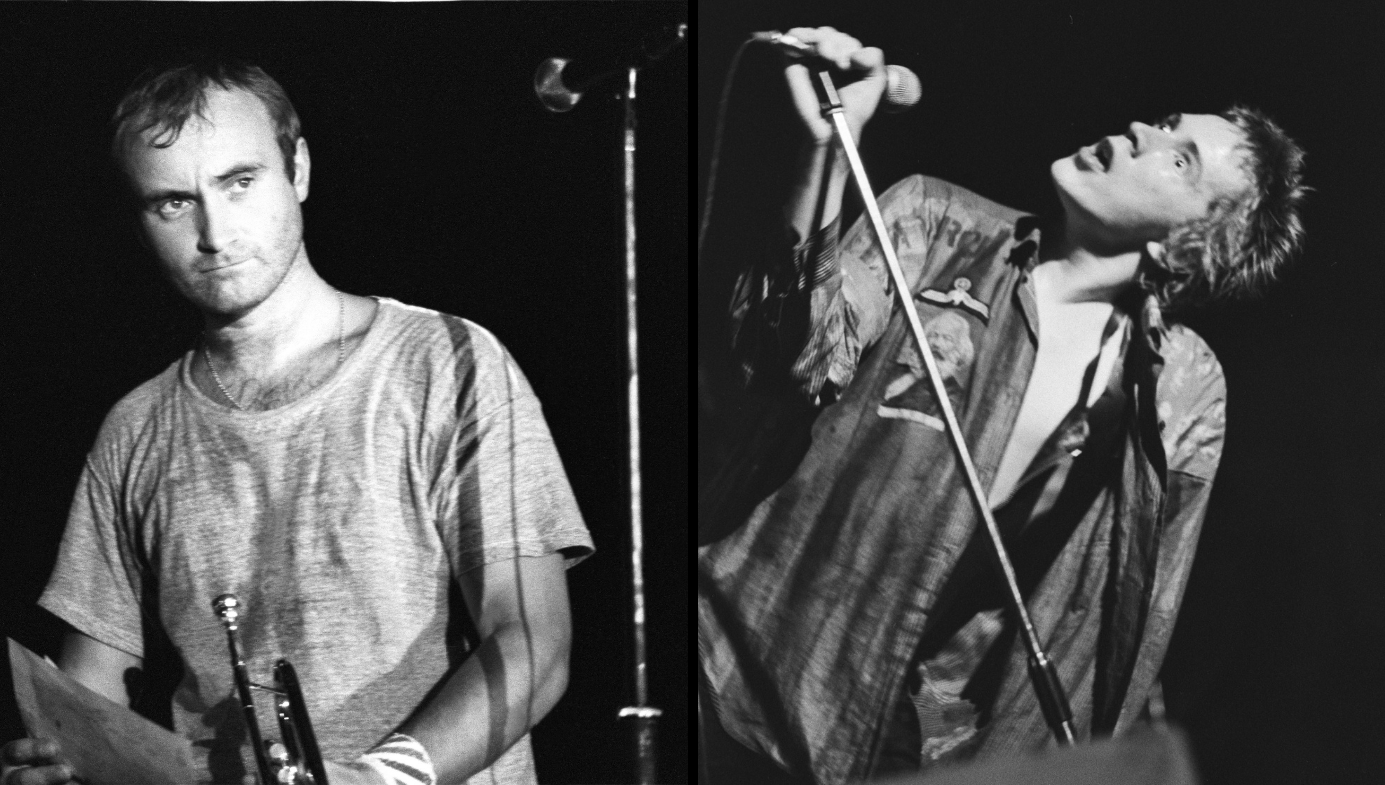

Rocker Crocked. Pistol Shot.

To say that Lydon has mellowed would be a huge over-simplification, not only of who he is now but of who he was then, both of which were media distortions if not inventions.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

~Thomas Gray, Elegy written in an English Country Churchyard.

I shouldn’t overstretch this frame—or shoe-horn the bunion-disfigured hoof of stubborn reality into an allegorical glass slipper—but old rockers do die, despite what it might say on the Father's Day Mug. And as they approach the Churchyard, their paths begin to converge.

Back in the Silver Jubilee year, 1977, The Sex Pistols were at war with progressive rock. A rather asymmetrical war, for sure, in which only one side probably knew themselves to be engaged, but still. The music press love a feud—what would Britpop have been without the North/South Divide?

The Sex Pistols were angry young men—sois-dissant situationists who hated the dreamy Jung men with their Hipgnosis gatefold album art, their endless concept albums and "song-cycles,” and their am-dram dressing-up box shenanigans. The progs were pretentious and effete and disdained, not only for being able to read music, but for littering their lyrics with symbols from the collective unconscious. It all came from doing too much prep—they were the decadent ancien regime to punk's snotty sans culottes.

Whether there was any truth to all this didn’t matter much. As mediated by their friends at the NME, the punks despised prog—a genre they regarded as anything but progressive. And Genesis were among the original sinners. True, it was a Pink Floyd t-shirt onto which Johnny Rotten had scrawled “I hate,” an alteration which amounted to all the wit he needed back then to get hired by Malcolm McLaren. But Genesis were the Druidic Lords of the iddly-diddly—the eye-wash and the whimsy that the bin-bag and safety-pin boys and girls found so contemptible.

The Pistols drew as much of their energy from the desire to make overfed rock dinosaurs like Genesis extinct, as they did from making music themselves. They wanted to see the carcasses of these privately educated fops littering the impact crater of punk rock, exposed for the cold blooded, lumbering, vegetative grotesques that they were. The nimble-witted likes of Rotten and Co. pogoed jubilantly on the wreckage of shattered Melotrons and twin-necked Gibsons and their long-overdue graves. Their hour—1977, year zero—had surely arrived.

That summer, the Pistols’ Jubilee-baiting single “God Save The Queen” was strongly suspected of topping the charts in the most contentious polling scandal until the 2020 US election, creating all kinds of embarrassment for a BBC that was still quite happy to have Jimmy Savile hosting Top of the Pops. We cackled along with Rotten's snarling intro to “Anarchy in the UK” in delight.

But Genesis remained a guilty pleasure. Six months later, The Sex Pistols had imploded, their last sour date played out in San Francisco. Only a decade earlier, the city had been home to the Summer of Love, but now it was hosting a small, private winter of fathomless discontent.

In March 1978, Genesis released ...And Then There Were Three..., the band’s first album since lead guitarist Steve Hackett announced that actually, he couldn’t anymore, and followed the band's former vocalist Peter Gabriel through the emergency exit. The new record was a commercial and critical success, especially in the States, and despite anticipating Twitter by a full 30 years, “Follow You Follow Me” gave them a top 10 single, and allowed the band to tour profitably in the States for the first time.

The new, shorter, punchier pop songs, shorn of the exuberant topiary and excess foliage of the earlier works, established a template for the next 20 years. As a three-piece, Genesis were regenerated, and ultimately grew to exceed their fans’ expectations—and their detractors’ worst fears—to become one of the biggest bands on the planet. An uncanny knack for hitting the sweet spot between album-oriented rock and chart pop elevated Phil Collins, in particular, to earn the epithet "ubiquitous.” Originally enlisted as the band’s drummer, Collins became, by several important metrics, the single most successful recording artist of the '80s—the decade of Madonna, Prince, and Michael Jackson. Johnny Rotten, meanwhile, discarded his punk moniker, and as John Lydon, had only the bitterest PiL to follow, attaining critical acclaim with discordant post-punk, but only fitful commercial success.

Forty-some years later and Genesis are once again on tour, and by a conservative calculation, taking box office of around three million quid a night. Lydon is on tour too, but he’s not singing (or indeed “singing” as my mother would still have it). Instead, he is giving an account of himself in spoken word, and settling a few scores for good measure. On Thursday last week, he followed me, a struggling stand-up comedian, onto the stage at the New Royal Theatre Lincoln, capacity circa. 450.

To be fair, Lydon sold it out, and I did not. But still, you know … Orders of Magnitude and all that. It's far from humiliating, but the hierarchy has survived. And if that were as much as one knew, it would seem to be a familiar tale of Might as Right—majesty and the ancient regime have been restored; money talks, even if it can’t dance. So, is this, then, the final vindication of Genesis? The triumph of patience, musicianship, and ambition over simplicity and attitude? Should Lydon lie down and accept defeat?

Let no man be called truly happy, while he yet lives. Lydon may be playing to a lower gallery, but he gives every impression of having fire in his belly and grit in his gizzard to spare. Genesis, meanwhile, judging not only from the publicity but also from the almost palpable physical discomfort of their lead singer, will almost certainly be making this their last lap of the Jurassic Park. Lydon might still get to pogo on their collective, corporate grave.

Phil Collins has made no secret of his “health challenges”—a lily-livered euphemism for a degree of disability and chronic pain which I suspect he’d prefer to describe as “crocked,” if not something stronger. The problem appears to be his spine, his once brass neck, which seems to have succumbed to the physiological punishment of a half-century spent hitting things with sticks. Operations—botched?—on three damaged vertebrae have left him unable to drum and barely able to walk. The Swiss air to which he exiled himself did not make a damn bit of difference.

It is said that all mammals have roughly the same number of heartbeats in a lifetime—whether small, fast, and short-lived, like a shrew’s or, huge, slow and venerable like an elephant’s. Perhaps the same goes for drummers. Collins’s career saw him drum for 40 years with one of the world’s biggest bands, and then on his own solo records and tours … and then take session work, too, just to keep his hand in. No wonder he's out of whacks.

It’s one thing to read about this. It’s quite another to see it relayed live onto a vast back-projection screen that dominates even the asiatic plains of the stage at the Manchester AO Arena. His enormous face—sunken-cheeked, belligerent, unshaven, etched with pain—seemed to be unaware of his command of the stage at times as it chewed and resettled its dentures. It was a vision of unvarnished truth, more suited to Beckett’s Endgame or Krapp’s Last Tape than the expected glamour and allure of the world-conquering rock star. The spectacle was deeply unsettling, as though we had been invited to observe an oblivious patient on a monitor, before discussing treatment options. And then he would flick his eyes up to meet ours—and we would realise that he knew, after all.

Collins may have issues with his actual spine, but watching his endurance onstage, I don’t think anyone could gainsay his metaphorical one, or his guts. There was sinew in this rejection of dignity, of polish, or even a bit of slap. He resembles an ageing, embattled king, determined to prove to a devoted court that, despite all his trappings of wealth and prestige, he remains unable to turn back the only tide that really matters. It was tough to watch. For those of us who loved the sheer romance of early Genesis, it felt almost like a rebuke.

There was a time when listening to a great Genesis song—compositions like “The Musical Box” and the band’s sprawling 23-minute 1972 masterwork, “Supper’s Ready”—was like exploring a sumptuous garden, replete with fountains and sundials and cucumber vines, caught in unexpected shafts of sunlight that you had forgotten since last you wandered in. Gorgeous melodies and labyrinthine musical arrangements were complemented by Peter Gabriel’s breathtaking lyrical originality, bursting with ideas, imaginative flights of fancy, and allusions to English literature, myth, and the King James Bible. Those songs left you with the sense that you had been gone for much longer than their allotted time on the disc would seem to allow. A great Genesis song was an opium dream, the musical equivalent of Where the Wild Things Are, and as the needle settled finally into the run out groove you would blink to find yourself back in the room, as the jungle growth withdrew into the wallpaper.

But this reverie could not last. The seeds of paradise’s destruction were already germinating in the vines of global ambition and compromise that reached into the sky like a monstrous beanstalk. This world was never meant for beauty as fragile as theirs, even if “fragile” was not the word that came to mind as you listened to the band pound through “Apocalypse in 9/8.” But did it need to come to this?

I remember Bruce Springsteen saying that his saxophonist Clarence Clemons—a huge bear of a black man who offset Springsteen’s scrawny white kid—allowed him to tell a bigger story than he was able to tell alone. There was something of this in what Collins brought to Genesis, too. The band formed at the ancient and venerable Charterhouse School in Surrey when its members were just 15 years old, and it was full of conservatoire-standard talent. Collins arrived later, replacing John Mayhew on drums in time to record the band’s 1971 LP, Nursery Cryme, and while he was by no means a guttersnipe, he was something more like an everyman who had not been born with a silver spoon stuck in his puckered gob. For many years, this helped broaden the band’s appeal and allowed them to stuff their bank balances like innocent geese.

Seeing Collins contorted in a wheeled chair, like Grandfather Smallweed in Bleak House, while his two bandmates swayed on either side of him, painlessly upright in elegant, soft grey fashions like Farrow and Ball in human form, bordered on the grotesque. It resembled a satire on the ineradicable nature of privilege and class, rather than evidence of the dynamic tension every band needs to achieve creative synthesis. It was everything the NME said punk disdained. But I can’t imagine John Lydon taking any pleasure in this at all.

To say that Lydon has mellowed would be a huge over-simplification, not only of who he is now but of who he was then, both of which were media distortions if not inventions. And, frankly, I'm not qualified to offer much insight into either. But I suspect that he is at least more willing to let us see his human side now. His wife of over 40 years, Nora Forster, has been suffering from Alzheimer’s for the last three and he has committed himself to her full-time care. In 2010, Forster’s daughter Ariane—better known as Ari Up, lead singer of female post-punk outfit The Slits—died of breast cancer aged just 48. Lydon knows something about human frailty, mortality, and loss.

I have the sense that after many years, not on the field of combat but behind the bare timber of the cheapest proscenium arch, the paint is wearing off both these Punch dolls. Both were iconic and pugnacious in their day, but human, all too human, too. Today, it is not prog, let alone Genesis, that attracts Lydon's ire, but what he perceives to be the betrayal of his ex-bandmates, who have sold out the Pistols’ musical legacy to a TV show—people that do indeed, as he sneered in PiL, see it as nothing more than product.

Lydon was years ahead of his time, on everything from the Savile row to the shark-infested waters in which he was swimming, but I doubt he will take much pleasure in seeing a fellow grafter—and émigré—working through pain to give his fans a chance to say one last farewell, to him and to each other. He might even feel a twinge of grudging kinship. They may not have reached the churchyard quite yet, but their paths are beginning to converge, as all must in the end. And, meanwhile, as the years wear on, who can be sure Her Majesty—God Save Her—won't bury the bloody lot of them?