Art

A Treasure Trove of Priceless Pornography

One might be skeptical about Pornhub’s claim that their interactive guide is a way to raise museum attendance in the wake of the pandemic-induced hiatus.

The art world’s initial encounter with the Hungarian-Italian porn star and politician Ilona Staller, better known as Cicciolina, was in her capacity as the muse of Jeff Koons. Koons’s “Made in Heaven” series of sculptures and photographs, which depicted the couple enjoying sexual congress in a variety of settings, rocked the 1990 Venice Biennale. Now, the 69-year-old Cicciolina is involved in another art-related project, this time starring in a promotional video for “Classic Nudes”—“Pornhub’s interactive guide to some of the hottest scenes in history at the world’s most famous museums.” “Classic Nudes” was launched by the adult entertainment platform on July 13th, and features erotic paintings and sculptures from the collections of London’s National Gallery, New York’s Metropolitan Museum, Madrid’s Prado, and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

The Uffizi in Florence and the Louvre were also originally included, but demanded the withdrawal of the associated images, citing fair use violations. Two weeks after the launch, 56 paintings remain on the site, accompanied by text descriptions and, in some cases, video guides. In-person museum visitors are furnished with interactive maps directing them to the physical locations of the works in the represented galleries. The site also embedded sexually explicit “reenactments” of half-a-dozen paintings—one for each featured museum—performed by a Barcelona-based duo coyly named MySweetApple. Four of these meticulously art-directed videos (Goya’s “The Naked Maja”; Gustave Courbet’s “The Origin of the World”; Edgar Degas’s “Male Nude”; Jan Gossaert’s “Adam and Eve”) remain on the site, with the two representing the Uffizi and the Louvre removed.

I have been a bit surprised by the apathetic reaction to “Classic Nudes.” The few articles that have been written about it mostly concentrated on the legal challenge from the Uffizi (and the anticipated legal challenge from the Louvre). The current vogue is for popularizing museums via interactive exhibitions (the Van Gogh immersive experience is one prominent example), outsourcing curating to museum staff (as in the upcoming show at the Baltimore Museum of Art), and expanding visitor outreach to frame the art in a way that won’t intimidate those for whom museum trips are not a regular weekend activity. So, it is strange to see this brilliantly simple engagement strategy viewed with caution, if not suspicion. The reason for this is obvious—the association of the project with a porn site, and the associated stigma. But such squeamishness ignores the origins of contemporary pornography in the erotic art of yore. By snubbing its own progeny, however wayward, the art world risks foregoing truth in favor of confabulated facades of asceticism and primness. Art history tells us a different story.

The second half of the last century witnessed some noteworthy reckoning with the erotic dimension of art. It started with the 1953 A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, delivered by the British art historian Kenneth Clark, which were subsequently published in book form as The Nude by Princeton University Press (1960). There, Clark challenges the assertion made in a 1933 text by his compatriot, philosopher Samuel Alexander: “[I]f the nude is so treated that it raises in the spectator ideas or desires appropriate to the material subject, it is false art, and bad morals.” Clark responds that “no nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling … and if it does not do so, it is bad art and false morals.” Alexander’s “high-minded theory,” writes Clark, “is contrary to experience.” He recognizes that paintings are often a “mixture of memories and sensations,” and as such, they necessarily convey eroticism to the viewer.

Speaking of Boucher’s 1737 work, “Marie-Louise O’Murphy,” Clark admits the nature of his reaction to this overtly erotic canvas depicting one of Louis XV’s many mistresses: “[B]y art Boucher has enabled us to enjoy her with as little shame as she is enjoying herself.” (Incidentally, this painting, also known as “The Blond Odalisque,” was a pendent for Boucher’s 1745 “The Brunette Odalisque,” one of the paintings at the Louvre originally included into the “Classic Nudes” project but later removed from the site.)

Discussing another Louvre painting, “The Pastoral Concert (Le Concert Champêtre),” attributed to Titian, Clark recalls Walter Pater’s comment that “our participation is sensuous and direct” as he explains that the aim of the painting is “to create a mood through the medium of color, form and association.” In some cases, eroticism figures straight into his descriptions (Clark refers, for instance, to the Fontainebleau School’s “stylish eroticism” as its main characteristic).

Unsurprisingly, the 1972 BBC television series, Ways of Seeing, based on an essay by John Berger and narrated by the author, opens its section on the nude in art with the distinction Clark draws between nudity and nakedness. But Berger’s contemplation of the nude is informed by the rise of second-wave feminism, and the acute awareness of objectified nudes. So, he presses the difference between naked as “being oneself,” and nude as being “seen naked by others, and not recognized by oneself.” For Berger, “a nude has to be seen as an object in order to be a nude.” He concludes that it is the spectator—or as he phrases it, “a male spectator-owner”—who defines Western oil painting where “most nudes … have been lined up by their painters for the pleasure of the male spectator-owner who will assess and judge them as sights.” It is the “spectator-owner” who is the recipient of the submissive gaze of the nude.

This apparent conflict between male spectator in the room and female nude on the canvas produced a peculiar cognitive dissonance in at least one feminist art-historian. Writing about Gustave Courbet’s pornographic 1866 painting, “Le Sommeil,” Linda Nochlin claims that her identity as both a woman and an art historian essentially forces her to “give up [her] status as a viewer.” Nochlin’s concern with the problem of the female nude availed to the male gaze, initially expressed in the 2006 seminar on Courbet, brings Berger’s argument full circle.

One of the most famous instances of bona fide fine art being censored as pornography is the 1988 controversy over displaying Robert Mapplethorpe’s erotic (or pornographic, depending on one’s point of view) X Portfolio in public venues. Janet Kardon’s “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment” exhibition, curated for the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Philadelphia, generated a prolonged and well-publicized debate on artistic freedom, standards of decency, and governmental support for the arts. Critic Dave Hickey saw the art community’s reduction of the photographer’s work into mere formalism as a missed opportunity to allow “a direct enfranchisement of the secular beholder” who is not ordinarily exposed to this type of challenging art. Hickey spoke about the failure of the “cloud of bureaucracies”—or, as he called them, “therapeutic institutions”—to embrace Mapplethorpe’s “vernacular of beauty” in favor of maintaining “the puritanical canon of visual appeal.” He lamented the suppression of the direct appeal to the beholder. In Hickey’s view, the prints of the X Portfolio were:

… exuding sophistication but wary of seduction, anxious about their pleasure and fearful of being manipulated to sexual rather than cultural ends by the flagrant ornamental display, suspicious that the “formal armature” of the imagery has been tainted somehow by its origins in situational erotics.

Form and content fused in Mapplethorpe’s photographs because both the erotic and the aesthetic share the same “rhetorical language and iconographic display.” The critic concluded that, as with Titian’s “Venus of Urbino,” “beyond the proclivity of the beholder, there is no way of sorting them [the erotic and the aesthetic] out.”

Eroticism is often an intentional part of painting and sculpture. Western painting is replete with clandestine portraits of royal mistresses in the guise of goddesses and shepherdesses, pseudo-didactic scenes of debauchery often involving visibly inebriated participants, and scandalous scenes in which members of a nuclear family engage in incestuous intercourse. Paintings of the Old and the New Testaments make up a formidable anthology of sexual misdeeds, immodesties, and improprieties. In the decade-and-a-half I have been teaching, I have shared this content with my students, because some works just are erotic in nature and purpose. This is especially true in the cases of Italian Mannerism, Rococo, and late 19th century academic painting in France. Three prominent examples come to mind.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s 1767 “The Swing” (aka “The Happy Accidents of the Swing”), now in the Wallace Collection in London, was commissioned by a nobleman who asked a respected academic painter Gabriel Doyen to depict him and his mistress. Doyen turned down the commission on the grounds that subject matter was too frivolous, and it was passed to Fragonard, whose specialty was wanton frivolity expressed through suggestive Rococo arabesques.

“The Swing” depicts the young man raptly gazing up the dress of his paramour, and the viewer is invited to share in his delight. The scene is made more piquant by the interesting sartorial fact that bifurcated underwear was not adopted for another four decades. Quel scandale! In another daringly obscene compositional detail, the view available to the male lover is evoked for the viewer by the coral pink formation of the young woman’s dress. The symbolism of mossy verdure that surrounds glistening pink vignette of the silk skirt is unmistakably erotic.

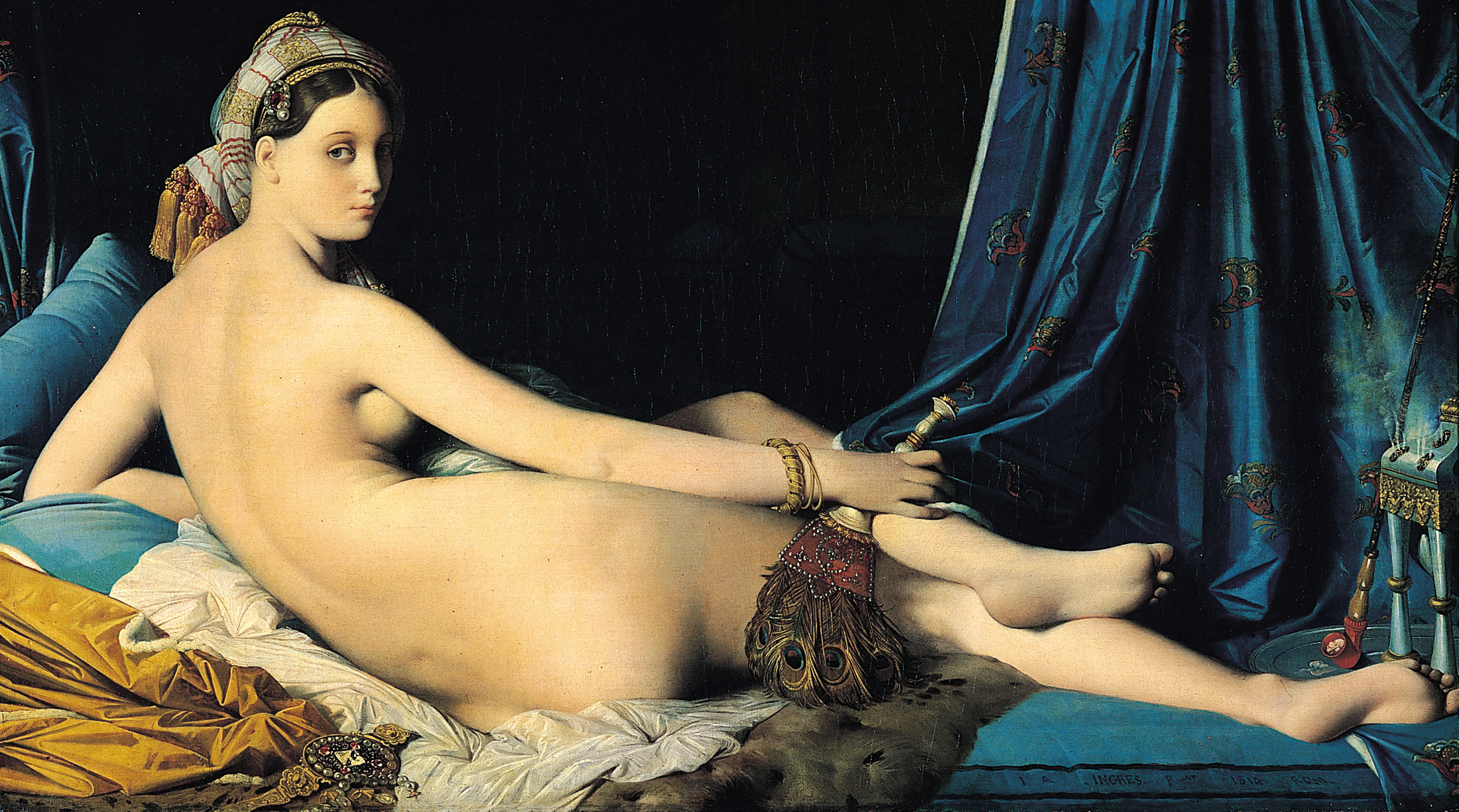

In another famous French painting from the Louvre collection, J.A.D. Ingres’s “Grande Odalisque” (1814), the young woman, whose occupational purpose it is to be a sexual plaything of the sultan, has an improbably elongated midsection. The reason for it is not bad drawing—Ingres was deservedly one of the most celebrated academic painters of his era—but his ingenious underscoring of what the odalisque’s mid-section signifies: her sex.

The following decades saw the rise of photography, and with it pornography. By the end of the 19th century, French academicians William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel perfected the erotica-in-the-guise-of-antiquity game. Their nymphs and goddesses looked as if they were copied (and some were!) from then-ubiquitous pornographic photographs. The pompous Salon judges, as well as the spectators and the patrons, voraciously consumed paintings of hairless nudes. Cabanel’s 1863 “The Birth of Venus,” now in Museé d’Orsay, proved so popular that after selling the original to Napoleon III, Cabanel was immediately made a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. That year’s Salon, where the painting was prominently displayed, featured so many goddesses of love, that it was dubbed “The Salon of Venuses,” and commemorated in Honoré Daumier’s eponymous cartoon.

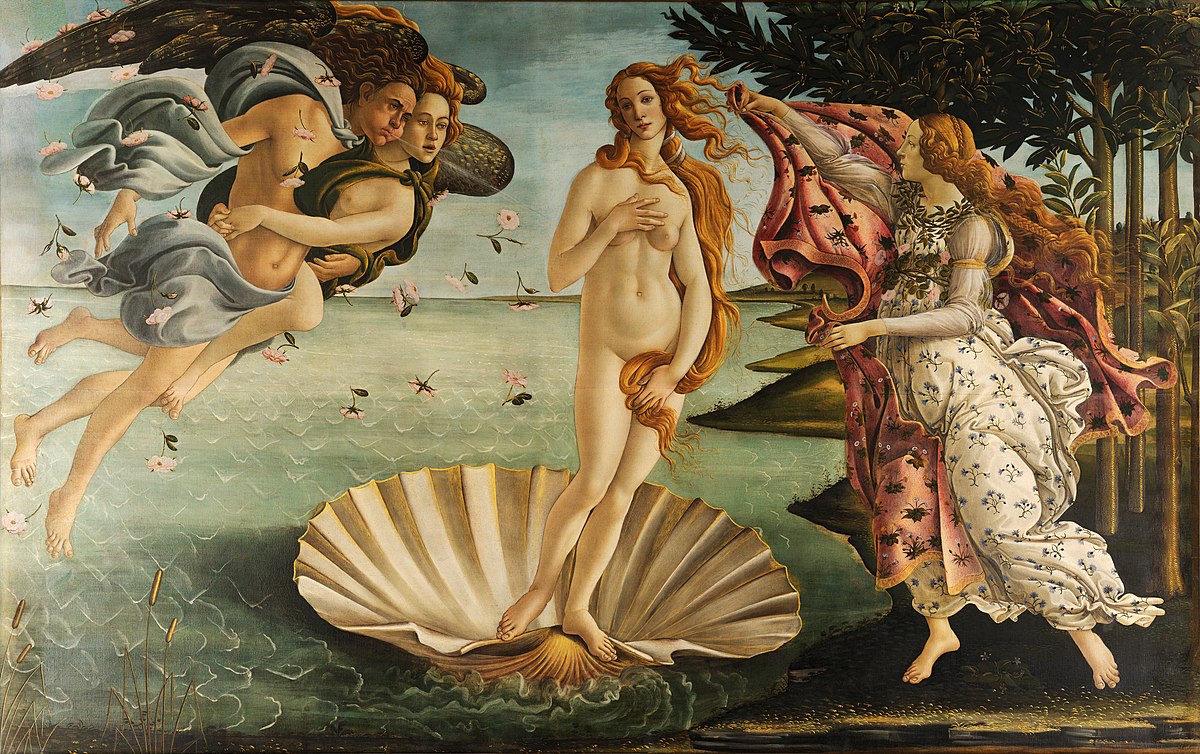

Speaking of Venuses, back in my own undergraduate days at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Professor Gail Geiger opened her discussion of Botticelli’s 1484–86 masterpiece, “The Birth of Venus,” with a fun fact: the Neo-Platonic goddess’s first abode was the bedroom of a teenage boy. Scholars no longer think this was the case, but the narrative held for most of the 20th century, and became an effective ploy for raising interest in fine art. After all, Neo-Platonism postulates that while a nude Venus is a physical incarnation of divine love, she is also the Celestial Venus.

The path to intellectual love lies through the arousal of physical love, and the painting takes this into account by placing its emphasis on eroticism. As Kenneth Clark put it:

Botticelli’s Venus does not deny the empire of the senses. On the contrary, the flow of her body is like some hieroglyphic of sensuous delight, and behind the severe economy of Botticelli’s drawing, we can feel how his hand quickens or hesitates as he follows with his eye those inflections of the body which mysteriously awaken desire.

Appropriately enough, the “Classic Nudes” promotional video culminates in a live reenactment of Botticelli’s Neo-Platonic love hymn. It opens with Cicciolina in the make-up chair, informing the viewer that “there is a treasure trove of priceless porn out there just waiting to be discovered.” The actress then leads the viewer along the halls of the Baroque palace in which the video is filmed: “Today, I am going to let you in on a little secret,” she says. What follows is hardly controversial: “Some of the best porn of all time isn’t on Pornhub. It can only be found in a museum.”

One might be skeptical about Pornhub’s claim that their interactive guide is a way to raise museum attendance in the wake of the pandemic-induced hiatus. Yet presenting work whose original subject matter is erotic, and sometimes intentionally pornographic, is not an instance of exploiting high art for base purposes, but rather an acknowledgment of its currency and abiding relevance. The gods and goddesses that populate the museums of Europe and America are still sexy. Because “some art can definitely be considered porn,” for all its NSFW content, “Classic Nudes” should not be seen as a predatory assault on Old Master painting, but as a democratizing project, one that could expand the museum-going audience by engaging their interest … in pornography.