Books

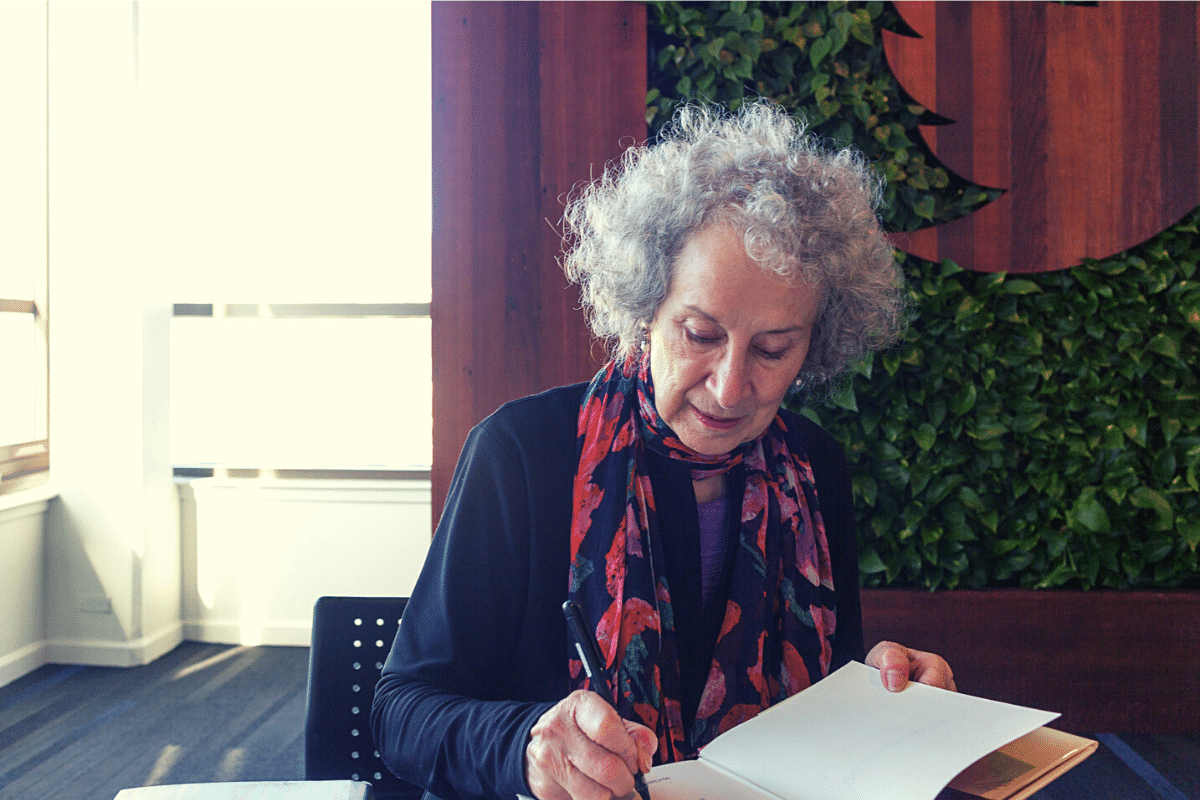

The Prophet of Dystopia at Rest: Margaret Atwood in Cuba

Canada has never supported the US embargo, and the countries’ good relations are for many Canadians a symbol of our independence.

Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it.

~Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

As a Cuba scholar, a student of literature and politics, and an enthusiastic reader of Margaret Atwood’s work, I have collected articles and media clips over the years related to the Grande Dame of CanLit’s many private and official visits to Cuba. Frankly, the file is thin. Generally, scholars engage with her important body of work (more than 60 books, fiction and non-fiction), without mentioning this topic. It is an interesting footnote, no more. Why interesting? Because it illustrates, in her case and as a pattern, how an inquiring mind sincerely committed to human rights and democratic values can turn off its critical antennae. Atwood allowed herself to become a compliant guest in a country that checks almost all the boxes of totalitarianism, minus extensive terror: a single-party state, no rule of law, arbitrary arrests (2,000 of them during the first eight months of last year), stultifying media (even Raúl Castro says so), and a regime of censorship that allows no freedom of speech, association, and only limited freedom of movement; a country with half-empty bookstores selling the same few official writers and hagiographies of the dear leaders.

I am not saying she ever became an enthusiastic apologist, as many Western writers and intellectuals did during the 1960s until the 1971 Padilla show trial. This is not like, say, a Sartre returning from Russia and announcing that cows produce more milk under socialism. Atwood has hardly said anything publicly about Cuba, as far as I know. Rather, Atwood in Cuba is more like a Sartre under the occupation, blissfully unconcerned about what is going on around her. I suspect that, were she asked if she considers Cuba a dictatorship, she would echo Justin Trudeau’s response to the same question back in 2016, and agree that it is. Maybe, like Trudeau, her answer would follow a pregnant pause, but she would be unlikely to deny that reality when forced to confront it. Nevertheless, with a little work, she has shown that she is able to ignore it.

Atwood travelled to Cuba for the first time in the early 1980s. She and her husband, the writer and avid birdwatcher Graeme Gibson (1934–2019), had been invited to participate in a cultural exchange by her former research assistant, who was then working as a cultural attaché at the Canadian embassy. Atwood tells this story in the introduction to a beautiful coffee-table book, entitled Cuba: Grace Under Pressure, written by Canadian writer Rosemary Sullivan with photographs by Malcom David Batty. Sullivan focuses on the private lives of Cubans, not the regime or its politics—“pressure” here refers to economic hardship, not the kind that results from living in a police state, and “grace” is a compliment to the Cuban nation for remaining fiercely independent. So it is a political book after all, just surreptitiously.

Atwood does not say much, but she does address the political question. “Nothing anywhere is as simple as we would like it to be,” she wisely writes, “but there are two verities that can be counted on: 1) no government is its people, and 2) birds don’t vote.” This is particularly true of countries in which neither birds nor citizens can vote. She also writes this:

Graeme promptly got arrested because he’d gone out early in the morning to watch birds, and hadn’t taken his passport—”We have a lot of trouble with people masquerading as spies,” a Cuban quipped later—and he’d wandered too close to something or other. He was stuck in a police station for hours while they tried to find an interpreter. Thus he was late for the hot-shot cultural lunch, and had to explain why. There were quite a few smiles and chuckles: a lot of the people at the table had themselves been arrested, under one regime or another, or at one phase of the Cuban Revolution or another. The story of Graeme’s arrest is still doing the rounds in Cuba, where they think it’s pretty funny.

Fortunately, Gibson, a prominent Canadian guest with a direct line to the embassy, never felt unsafe. It is a rare privilege to be able to trivialise arbitrary arrest in this way, as mere fodder for dinner party conversation.

In 2017, Canada was the guest country of honor at the Havana International Book Fair. A contingent of more than 30 Canadian authors plus several performing artists were invited. Atwood, for whom it was not a first as a Fair’s guest, was the star of the delegation. The speaker of the Canadian Senate presided over the ribbon-cutting ceremony at the opening of the Canadian pavilion. Nobody seemed to notice how highly parametered (from “parameter”: a term used in Cuba to designate the lines not to be crossed) this event always is. The stands overflow with children’s books, but critical literature is a rare commodity. Anyone who wants to see a truly international book fair in Latin America, replete with free discussion and vigorous debates about books and authors, should go to the one in Guadalajara, Mexico, and then compare.

The Havana Times journalist Barbara Maseda reported that during one of the official soirées, Atwood was asked about her favourite Cuban writers. Her response: “Carpentier, of course. Martí. Miguel Barnet. Nancy Morejón. Pablo Armando [Fernández]. Abel Prieto.” She knows there are more, but those were the names that came to mind. Maybe that was just an unrehearsed answer. Atwood never writes about Cuban literature, and her non-fiction work includes just one short comment on a Latin American writer—Gabriel García Márquez, the one every educated Anglo-Saxon knows. Her world is Anglo-American literature, and that is surely expansive enough for one person. But as Maseda perceptively remarks, her choices seemed to be “taken out of a manual of officially approved writers.” “The selection,” Maseda adds, “speaks, perhaps, of the nature of the links that she has kept with the country and its culture: ties built around diplomacy and official events, devoid of the restless curiosity one would expect from the talented literary critic.”

Martí is the nation’s “apostle,” widely considered to be among the best Latin American writers of his time. Carpentier was indeed a great writer. Barnet wrote one memorable book of ethnology and was the boss of the artists and writers “union” (in the Soviet sense); Morejón and Fernández are respected but minor authors, and Morejón also occupied political positions in Cuba’s cultural bureaucracy. Almost nobody read Abel Prieto’s books, but everybody knows Prieto the minister of culture and cultural apparatchik. Last fall he was particularly vocal denigrating the young artists and independent journalists demonstrating for more freedom of expression in Cuba.

According to the Western Canon of literary critic Harold Bloom, five of the 18 greatest modern Latin American writers were Cubans: Alejo Carpentier (1904–80), José Lezama Lima (1910–76), Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1929–2005), Severo Sarduy (1937–93), and Reinaldo Arenas (1943–90). Except for Arenas and Cabrera Infante, the others wrote most of their books before the revolution and often abroad (Carpentier and Sarduy). Lezama Lima was censored for decades on account of his homosexuality, as was Arenas and another important Cuban writer, Virgilio Piñera (1912–79). Cabrera Infante (a Cervantes Prize winner, the Spanish equivalent of the Booker Prize) and Arenas remain censored on the island to this day. As were Fernández and Morejón during the 1970s. Arenas and Cabrera Infante were fierce and vocal critics of the dictatorship and died in exile. Until very recently, they were officially and completely ninguneados in the island, meaning they were actively erased from official memory. To put it in the parlance employed by Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale, they were “unpersoned.”

The performing artists who were part of the Canadian delegation may not have known all this (although, when I visit a country, I am always curious to know if people like me are well treated there.) But Atwood is a patron of Index on Censorship, a vocal champion of Amnesty International, and a recipient of the English PEN Pinter prize for her work defending writers’ rights. And, as mentioned, she is a frequent visitor to the island. Imagine visiting Moscow for the nth time during the Cold War, attending some Canadian-Soviet cultural event or other, and announcing that the very best Russian writers were Maxim Gorky, Feodor Gladkov, and Alexander Fadeyev, rather than, say, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Anna Akhmatova, and Vasily Grossman.

One needs to work at ignoring reality because it requires a conscious effort to look the other way. Atwood’s particular brand of imagined dystopia—amplified right-wing fantasies—ruffles no feather in the milieu she navigates. Not much bravery is required—at least, nothing like that mustered by precursors like Yevgeny Zamyatin or George Orwell, who is one of her favourite authors.

From 1984 to The Handmaid’s Tale

Atwood’s gratitude for the official hospitality she received in communist Cuba has meant that some of her works have been translated into Spanish and made available on the island: A book of poetry, as well as an anthology of Canadian writers, entitled Desde el Invierno (“From the Winter”). But not The Handmaid’s Tale.

She wrote The Handmaid’s Tale in Germany, just before the fall of the Berlin Wall. When German director Volker Schlöndorff’s cinematic adaptation was released in 1990, there were two screenings, one in West Germany and the other in East Germany. “And the reaction of the audiences was very different,” Atwood later recalled. In West Germany, “they’re talking about aesthetics and directing and, you know, colour choices and biographies and things like that.” In East Germany, “they watched it very, very intently. And they said, ‘This was our life.’ They meant the feeling that you couldn’t trust anyone.” As she also remarked, “There were a lot of people reporting on a lot of people. Not because they were women and not because they were men, but because that’s what happens in totalitarianisms.” Guess which country coached the Castro regime on intelligence and the surveillance of its own population?

The literary inspiration for her bestseller was Orwell’s 1984, the most famous dystopian novel of our time. She read it often. 1984 was censured in Cuba until 2015. Now Cubans are permitted to own their own copy, assuming they can find one. The two novels belong to the same family of political fiction, but they differ on how they apply to a country like Cuba. 1984, like Animal Farm, is an allegory about communism. It is also a paradigmatic case of intramural criticism, since the USSR was at the apex of its popularity among the Western intelligentsia and Orwell identified as a socialist. Atwood knows about life under that kind of regime, as illustrated by her comment about East Germany.

But The Handmaid’s Tale was informed by her studies of 17th century America and its classist and Puritan values. The Divine Republic of Gilead was inspired, not by the atheist police states in Eastern Europe or Latin America, but by America’s history of religious witch-hunts in Salem and elsewhere—a mix of reactionary American Christianity and Khomeini’s theocracy in Iran, although she does allow that the danger comes from absolute power, not religion per se. For all her avowed debts to 1984, her novel has more in common with Boualem Sansal’s remarkable book, 2084, La Fin du Monde, which depicts religious extremism in some totalitarian caliphate. On the other hand, in one of her essays on Orwell and the possibility of totalitarianism, she talks about how new threats are emerging from “open markets” and “upgraded technology.” Since those led to the demise of European communism, I expect Cuban officials were quick to agree.

Cuba is one of the few real countries mentioned in The Handmaid’s Tale. At one point, a “Commander”—an authoritarian official from the ruling class—allows himself, mischievously, to tune in to an illegal radio station operated by the opposition: “Damn Cubans,” he says. “All that filth about universal daycare.” “Radio Free America,” as it is of course called, is not (or not just) the obverse of US-run Radio Free Europe, but conceivably, of Miami-based Radio Martí. A country does not need to be communist to have universal daycare, but the reference to Cuba invites us to conclude that the dystopian Gilead and the US have reactionary anti-communist dispositions in common.

Furthermore, although she resists the characterization of her bestseller as a “feminist novel,” the plot revolves primarily around the victimization of women. Men (white men, in particular) have occupied the few real positions of political power in Cuba since the revolution, but officially the government is supportive of gender equality, and women’s reproductive rights are not at risk. And Atwood’s dystopia unfolds in a futuristic (but, she insists, plausible) US. Not a bad conversation-starter with Cuban officials.

On her way to Cuba in 2017, Atwood said she was curious to know what Cubans thought about Donald Trump. After his improbable electoral college victory, The Handmaid’s Tale soared up Amazon’s bestsellers lists, as did Orwell’s 1984. As she put it, there are elements in the novel that are “increasingly resembling the ideas of some US lawmakers.” She and her hosts no doubt found much common ground on how Trump might turn the US into a dictatorship. But Trump is no longer in the White House. He flouted democratic norms, but the rule of law, most of the media, and the country’s system of checks and balances reined him in. Trump is out because of something that has not happened in Cuba since 1948: a free and fair election. Fidel and Raúl retired at a time of their own choosing, after decades of total power. Besides, a good deal of evidence suggests that the Cuban leadership preferred dealing with a churlish Trump to a more conciliatory but harder-to-handle Obama, whose visit to the island in 2016 created a panic in ruling circles. Dictatorships need enemies: doesn’t Atwood say that somewhere?

The Handmaid’s Tale probably won’t be translated in Cuba anytime soon. It remains a powerful warning against oppression, state surveillance, state-run media, official indoctrination, and repression. In the novel, the secret police is called the “Eyes.” In Cuba, the watchdog neighbourhood committees—officially called Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR)—are also known as the “eyes and the ears of the revolution.” As Mark Twain once observed, “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.”

The question of artistic responsibility

These thoughts inevitably lead to a time-honoured discussion about the responsibility of the artist. I have never been able to adopt a settled position on this topic. So here are two opposing views: I prefer the first with respect to Atwood, but the second deserves consideration.

1984 ends with an appendix, from which we learn that in an even more distant future, Big Brother has still failed to fully impose the totalitarian jargon known as Newspeak. The Handmaid’s Tale includes a similar optimistic addendum, and it is not a coincidence. Atwood once wrote that “Dystopian novels should always end on an optimistic note” (or be complemented by an optimistic sequel, like Atwood’s 2019 follow-up, The Testaments). But Orwell was not glibly optimistic; he wanted his readers to understand that the ultimate bulwark against totalitarianism is language itself. His novel reminds me of something Mexican poet Octavio Paz once said: “When a society is corrupted, the first thing to gangrene is language. The critique of society, therefore, begins with grammar and with the re-establishment of meanings.”

For Orwell, this rule applies especially but not exclusively to totalitarianism—read for instance his 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language.” Orwell argued that, given the importance of language and its centrality to critical thought and individual autonomy, the writer has a special mission and responsibility to “live in truth,” as Václav Havel would later put it—even when it is uncomfortable to do so, as it certainly was for a left-wing writer like Orwell after the war. Orwell’s appendix is not about hope, it is a warning. Defending freedom of speech is not a part-time responsibility for a writer, especially one who hopes to expose and denounce political oppression. Therefore, writers like Atwood have a particular responsibility not to drop their gaze when this most precious right is violated.

The second view holds that writers have a right to live apolitical lives. Atwood once wrote: “Artists are always being lectured on their moral duty, a fate that other professionals—dentists, for example—generally avoid.” Isn’t she right? Why can’t writers go on vacation, physically and intellectually, like everybody else? Politics is not their precinct. Their work is about observing and imagining various possibilities of existence, as Milan Kundera put it. One can think of more than a few great writers and artists whose morality left much to be desired. What they really need, in fact, is the permission to be free from responsibility from time to time.

In this particular case, after all, Atwood’s irresponsibilities have generally been venial. She was just mostly polite, in a country that is not Sweden but isn’t Nazi Germany either. She never publicly said anything like “Viva Fidel Castro,” as a former Canadian Prime Minister did in 1976, during the most repressive period of the Castro regime. Nothing she has done or said significantly departs from what a liberal senator might say in similar circumstances. The main sticking point with this view is that Atwood is a prophet of dystopia, the canary in liberty’s coal mine, which makes it harder to give her a pass.

In a sense, Atwood’s apparent lack of interest in the depredations of Cuba’s autocratic regime are very Canadian. Canada has never supported the US embargo, and the countries’ good relations are for many Canadians a symbol of our independence. Canadian policy toward Cuba, Trudeau declared in 2016, is “one of the ways we reassure ourselves that we are our own country.” Linger on that sentence for a moment, and read it again. It is quite an amazing and pathetic lament for a nation from a sitting prime minister, but it offers another possible interpretation of Atwood’s decree that “no government is its people”: one can have warm feelings about the first, without thinking or caring much about the second.