Activism

When Journalism Blurs Into Activism—A Canadian Case Study

This all began with an imaginary teachers’ manual. It ended with us challenging Canada’s self-described “national newspaper” about a range of stories in which ideologically-driven narratives seemed to trump fact.

We are two long-in-the-tooth Canadian journalists who began our careers in the 1980s. We’ve written investigative pieces about AIDS, alternative medicine, drug-money laundering, health fraud, and chiropractic (which we co-authored a book about in 2003). Paul also has been a journalism professor at the University of Western Ontario, while Wayne founded Southam InfoLab, a research unit for a large Canadian newspaper chain.

While neither of us is a scientist or mathematician by training, we learned that the correct reporting of facts and data is an important component of good journalism. We also learned how easy it is for even objective journalists to garble, ignore, or misunderstand the numbers they cite in their articles. Many writers, ourselves included, start their careers with only a tenuous grasp of many basic mathematical concepts. We generally either teach ourselves how to become informed and competent laypeople, or we recognize our limitations and avoid stories that require these analytical abilities.

As part of this process of learning, we have taught ourselves how to identify red flags when we read stories written by others. It continues to surprise us how many otherwise good articles in high-quality publications reflect a misunderstanding of statistics. As the case study below demonstrates, this trend is particularly worrying now that media outlets that have traditionally held themselves out as politically centrist are openly exhibiting a progressive bias. In the past, when a publication made an error, one might reasonably expect its editors to acknowledge it when it was pointed out. But a growing number of journalists now seem more interested in being ideologically compliant than factually sound.

* * *

On February 6th, the Toronto-based Globe and Mail newspaper ran an opinion piece titled “Complacent Culpability” (or “Canadian Complacency Is the Killer of Collective Change,” as it appears online). The author, Rachel Ricketts, describes herself as “a spiritual activist and mystic disruptor seeking liberation for Black and Indigenous women, femmes and non-binary folx.” In a passage about systemic racism in Canada, the author related an episode during her kindergarten schooling in British Columbia when “my white teacher attempted to hold me back from Grade 1, explaining to my mother that my Black brain wasn’t as large as those of my white classmates. The sentiment apparently derived from her teachers’ manual in 1989.”

If true, this would be quite shocking. While 1989 may seem like a long time ago to young readers, it wasn’t exactly the antebellum era. It strains credulity that such a manual, if it were ever employed by British Columbia educators, were still in use in the late 20th century. It was clear from the comments that appeared below the column that other readers, too, considered this a strange claim. One self-identified former teacher wrote, “I taught from 1979–2013 and never heard of any [such] manual. Furthermore, it is inconceivable that any [provincial] ministry document from that era would have contained such a gross generalization, physiological or otherwise, based on race.”

The Globe and Mail has sometimes been described as Canada’s newspaper of record. And this seemed like a serious journalistic error on a matter that the author herself rightly describes as being of national importance—specifically, systemic racism. So, we wrote to the Globe’s public editor, Sylvia Stead, indicating that it was “impossible to believe that in 1989, a teaching manual in Canada would spout disproven pseudoscience … Did the editors who vetted this piece ask Ms. Ricketts for some evidence that this claim—because it is not an opinion, but a statement of checkable fact—is true?” We pointed out that this kind of dubious claim unfairly maligns the education system and the teachers who work within it. By presenting the case for systemic racism on the basis of dubious facts, it also detracts from the credibility of other, more realistic, claims made by writers (Ms. Ricketts included) about the difficulties faced by non-white people in our society.

Ms. Stead, a Globe veteran who became the newspaper’s first public editor nine years ago, told us she agreed that the dubious claim had been stated “as fact”; and then, in a subsequent message, told us, “we have fixed the reference. I think the writer meant it as a recollection and not a fact, and frankly, that should have been caught by an editor. I spoke with the editor about it and he agrees. Appreciate hearing from you. It’s a good teaching moment.”

The new version reads as followed: “In kindergarten, my white teacher attempted to hold me back from Grade 1, explaining to my mother that my Black brain wasn’t as large as those of my white classmates. The teacher claimed it was from her teachers’ manual, and had my mother not threatened to sue the school board my educator’s racism would have scarred my academic record from its inception.” There’s also an editor’s note at the bottom that reads, “This article has been updated to clarify that there is no evidence a teacher’s claim was in a manual.”

In other words, the “fix” effectively consisted of inserting the word “claimed” in reference to the unsupported statement. Yet the corrected version still indicates that the teacher’s racism was informed by the sort of educational environment in which one might reasonably expect such a teaching manual to be used. While such terms as “claim” (or “suggest” or “allege”) can be used to protect a writer (and his or her editor) from the accusation that they are peddling falsehoods, they typically don’t protect readers from coming away misinformed.

As journalistic veterans, we understand that writers and editors often push back when their colleagues ask them to publish corrections or clarifications: It hurts their pride (though we would argue that not correcting an error is more damaging to their reputations in the long run). We also know that there is a certain stereotype surrounding older readers who harp on published inaccuracies and mistakes. And so we didn’t push Ms. Stead on this issue, lest we be dismissed as pedants or cranks. Perhaps Ms. Stead was right that this would prove “a good teaching moment.”

But then two weeks later, the Globe published a much longer piece—more than 4,000 words—titled, “How Canada’s sex traffickers evade capture and isolate victims to prevent their escape.” The piece, written by immigration reporter Janice Dickson, includes the emotionally searing stories of three women who’d been sex trafficked and escaped. It was an interesting feature full of well-reported human-interest details. But both of us were struck by a strange omission. As the title indicates, the piece is presented as an overview of a general trend that suggests a failure of Canadian policy. (The online sub-headline is: “Some women are moved across the country. Others are lured by traffickers at school. Many of them know the perpetrators who keep them isolated and dependent on them.”) Yet despite the article’s length and prominent placement, it didn’t contain any statistics regarding the number of Canadian women victimized by sex trafficking, which is the crux of the issue. (Full disclosure: Ms. Dickson was a student in one of Paul’s classes at the University of Western Ontario in 2013).

Oddly, in the same print edition, we did find a number. It was contained in a related op-ed penned by Julia Drydyk, the executive director of the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking, which had just released a report entitled Human Trafficking Corridors in Canada. The two articles were companion pieces. As of this writing, in fact, Ms. Drydyk’s reference to her group’s newly published report is hyperlinked to Ms. Dickson’s article, which, in turn, quotes Ms. Drydyk at length and focuses closely on her organization’s conclusions.

In Ms. Drydyk’s op-ed, she writes that “between 2009 and 2018, there were more than 1,700 incidents of human trafficking reported to law enforcement in Canada.” Since the article is about sex trafficking (these being the first two words of the headline), we naturally interpreted this to mean was that there were 1,700-plus cases of human trafficking involving sexual exploitation. (The full title of the opinion article is “Sex trafficking is a game where the ‘Romeo pimps’ always win, and that has to end.” The term “Romeo pimp” refers to a human trafficker who seeks to manipulate a woman by inducing her to fall in love with him.)

But as an examination of the cited Statistics Canada data shows, this number (the reported figure is 1,708) refers to human trafficking overall, of which sex trafficking is only a subset (albeit a “prevalent” one, as Statistics Canada reports). Human trafficking involves “the recruitment, transportation, harbouring and/or exercising control, direction or influence over the movements of a person in order to exploit that person, typically through sexual exploitation or forced labour.” The subset described as sex trafficking includes only those who “are sexually exploited when forced into prostitution or forced to perform sexual acts including exotic dancing or the production of pornography.” In practice, the United Nations notes, “two major categories of transnational activity can be identified: trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation, and labor exploitation, including the use of child labour.”

That same database of 1,708 cases comprises the basis for a chart contained in Ms. Dickson’s lengthy article, illustrating the per-capita police-reported incidence of human trafficking in Canada on a province-by-province basis. Like Ms. Drydyk’s op-ed, this article was presented to readers as being specifically about sex trafficking, not all types of human trafficking. Yet these statistics are included in a way that serves to effectively conflate the two categories in a reader’s mind.

We decided to analyze the numbers for ourselves. This is certainly not because we have any particular objection to journalists who raise awareness on issues related to human trafficking (of any kind), but because we were beginning to notice an unsettling trend.

What Statistics Canada reported is as follows:

Overall, between 2009 and 2018, police services in Canada reported 1,708 incidents of human trafficking, an average annual rate of 0.5 incidents per 100,000 population. Police-reported human trafficking accounted for 0.01% of all police-reported incidents over this period. When looking at annual data, the number and rate of human trafficking incidents steadily increased after 2010, peaking at 348 incidents and a rate of 1.0 per 100,000 population in 2017 [before decreasing in 2018]. As noted, the increase observed over this period may reflect not only an increase, but also better detection, investigation, and reporting of human trafficking by police. In 2018, there were 315 police-reported incidents of human trafficking, 33 fewer incidents than in 2017, and the rate also declined slightly (to 0.9 per 100,000).

Many of these human trafficking cases involve sexual predation. Of the 1,708 police-reported incidents during the decade-long period that spans the years 2009–2018, “56% involved human trafficking only, while the remaining 44% involved at least one other violation. When there was an associated violation, it was most commonly in relation to sexual services. Since 2009, close to two-thirds (63%) of all human trafficking incidents with secondary violations have also involved an offence in relation to sexual services.”

Applying the 44 percent figure, we can determine that about 752 of the 1,708 total human trafficking cases between 2009 and 2018 involved at least one other alleged violation. And 63 percent of those—about 473 cases—involved sexual services. That works out to an average of about 47 per year. Of course, that number is a lot less scary than 1,708—which is presumably why it doesn’t appear in the Globe and Mail’s reporting. (Just to make sure we understood the numbers correctly, we reached out to Statistics Canada by email to double-check. An analyst confirmed our analysis in this respect.)

We recognize that these numbers will serve to undercount the real problem of sex trafficking for all sorts of reasons. Many cases will go undetected by police, and so never make it into the official government data. Moreover, some of the other listed “associated violations” also involve sex, such as sexual assault (though the data isn’t presented in a way that allows us to know how many of these cases also involve sexual services). Moreover, it is hardly unusual for police to focus on the crime that is easiest to establish—and so many cases of sex trafficking may end up being categorized as simple human trafficking if the sexual component is more difficult to prove. In a 4,000-word article, all of this might have been explained.

Of course, even a single case of sex trafficking is one too many. But in an article that purports to demonstrate the known scope of the problem, it is strange that all the aforementioned information was left out. Perhaps the most important fact for most Canadians interested in this issue is the baseline number of known sex trafficking cases per year. For the period in question, the data tells us that this number is 47—a little less than one per week in a country of 37 million people.

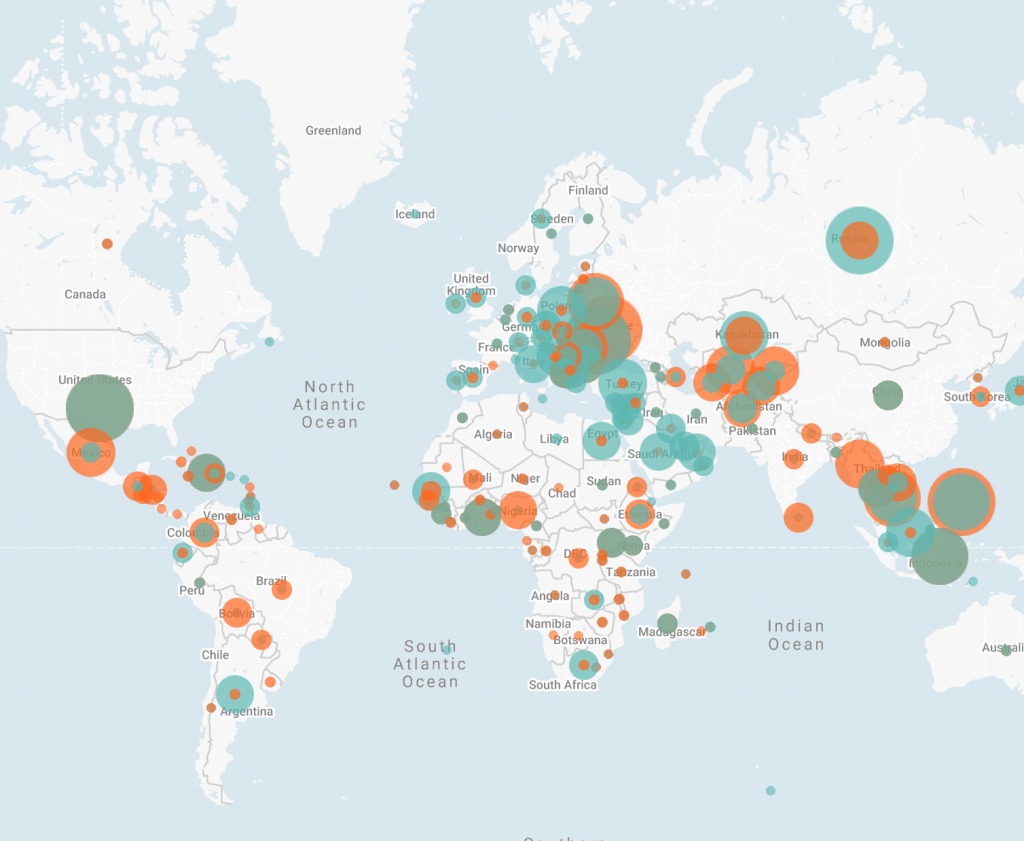

A good-faith effort to educate Canadians about the scope of this problem would also situate Canada within a comparative international context. Though differences in national reporting protocols make international comparisons difficult, data collected by The Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC) indicates that Canada’s trafficking volumes are positively minuscule compared to those of most other Western nations. (Here we are referring to all forms of trafficking.) This is indicated by the image below, which maps the CTDC’s database of approximately 91,000 trafficking victims by nation of citizenship (orange) and exploitation (green).

All of this information is in the public domain, and would have been available to both Ms. Dickson and her editors. Yet none of it was included by the Globe, leaving readers with the impression that Canada is suffering a sex-traffic crime epidemic.

We contacted Ms. Dickson with our concerns about her omissions. “Sexual trafficking is a vile crime,” we noted in our correspondence. “All the more reason to be cautious about reporting it.” She replied that “I’ve been covering this story for two years, and I stand by the facts. Please email our public editor if you feel there are errors.”

This brought us back to Ms. Stead. In our correspondence, we described similar concerns we had with another piece that Ms. Dickson had written (entitled “Only Ontario and Nova Scotia use Crowns who focus solely on sex trafficking”). Ms. Stead responded promptly, indicating that the Globe wouldn’t be issuing a correction.

But in fact, we hadn’t asked for a formal published correction—because, to be fair, nothing Ms. Dickson had written was explicitly false. We hadn’t claimed that it was. Our complaint, rather, was that the reporter had juxtaposed her material in a way that clearly would cause readers to misunderstand the scale of this serious problem.

Our final exchange with the Globe came following the publication of a column by Elizabeth Renzetti on the equally serious (and somewhat related) topic of femicide, a subset of homicide defined by one prominent academic as “the misogynous killing of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure, or a sense of ownership.” In a March 24th column titled, “The most dangerous place for women is behind closed doors,” Renzetti properly decried femicide, but then performed a journalistic maneuver analogous to Ms. Dickson’s—by implicitly conflating the number of all women killed in Canada (a measure usually called “female homicides”) with the much narrower category of femicide.

At one point, she notes that 160 women were killed in Canada in 2020, and then proceeds to describe an underlying climate of misogyny—“an ideology that denigrates and dehumanizes women … whether the femicide takes place on a street, or in a workplace, or in a home.” But of course, not all female homicide victims are killed by men (though most are). For 2020, the number of female homicides perpetrated by men is 128, according to the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability. And of those 128, we don’t have any definitive statistical understanding of how many of the killers had misogynistic motivations, which was the declared theme of Ms. Renzetti’s article.

Historically, the definition of “femicide” has been contested, including among feminists, with some using the word to describe all or nearly all female homicide victims; while others use it in a more narrow sense consistent with the definition Ms. Renzetti provided in her column. We have no particular view on which is the appropriate definition. What we object to is a journalist citing the narrow definition alongside data that corresponds to the broader category.

Of course, this all may seem like nitpicking to some: The bottom line, surely, is that systemic racism, sex trafficking, and femicide are serious issues that require a serious policy response, and that everything else is mere detail.

But professional journalists have long operated on the basis that details really do matter, especially when it comes to life-and-death matters. There are hundreds of important problems that our governments must address. Reporting honestly on these problems helps inform the creation of coherent, responsible, and balanced policies. Even if the data contained in an article has been rigorously fact-checked, reporting that data in a way that’s calculated to give readers an exaggerated sense of fear or urgency is an intellectually dishonest exercise that can distort public priorities.

These are just a few examples of what we fear is a trend among journalists who have become de facto activists, and fall in lockstep with popular causes at the expense of clear, factual reporting. The fact that we happen to agree with many of these causes isn’t material to our argument.

Readers will no doubt see parallels to other media outlets, and other subjects. When it comes to matters related to identity, in particular, it now seems that certain facts have been deemed taboo, while dubious claims are given the air of truth if they accord with a favoured ideological position. This is dangerous ground for the journalistic profession. If you let your convictions taint your reporting, then you betray a fragile trust with readers.

In all cases, the journalists involved will surely claim that their heart is in the right place, and that they aren’t deliberately spreading misinformation. But if that’s the low bar members of our profession are now being asked to clear, then it’s unclear how we’ll be able to distinguish bad journalism from good propaganda.