Top Stories

A Cardinal Sin

My efforts and motives in instigating Cardinal Conversations, in response to undergraduates’ requests, and in defending the program against the assault upon it were simply ignored.

I was brought up to think of a university as a haven for free thought and free inquiry; a place where established scholars and students communicate ideas, in both directions; a place where old thoughts and new are subjected to rigorous examination.

I was therefore appalled by the accusations made against me at a live-streamed Stanford University Faculty Senate meeting on February 11th and published online by Joshua Landy, David Palumbo-Liu and two other faculty members. I was included in a group of some half-dozen Hoover fellows who were said to have “abused” the position of the Institution and “quite possibly, contributed to significant public harm.” Landy expressed astonishment that I am “still on the roster” and that Stanford somehow failed “to publicly censure” me.

Like Palumbo-Liu, Landy is a professor of comparative literature. He is the author of two books: Philosophy as Fiction (Oxford, 2004) and How To Do Things with Fictions (Oxford, 2012). In his presentation to the Faculty Senate, Landy chose to present his statements concerning me as fact. Once again, however, he was doing things with fiction.

Landy made no effort to contact me before making his accusations. He based his claims on a 2018 article in the student newspaper, the Stanford Daily, a piece that was not made any more true by its being replicated elsewhere, and he ignored my own published refutation. An elementary understanding of context, not to mention prudence, might have led someone levelling such an accusation to acknowledge that his target had publicly rebutted the allegations against him. To repeat a false allegation is bad enough. To repeat it as if it is unchallenged fact is unacceptable, whether as a matter of fairness to a colleague, or of good academic practice.

At the time of the events in question I was advised to say as little as possible, on the basis that the storm in the campus teacup would blow over. When false accusations continue to circulate three years later, and not only at Stanford, that assumption appears naïve. The time has come to set the record straight.

Free speech matters more to me, I suspect, than to a scholar of French fiction. It might even be said that my family came to Stanford in 2016 as free-speech refugees. My wife Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s public criticisms of her former religion are regarded by Islamists as blasphemy, punishable by death. Her name appeared on an Al Qaeda list of 11 targets which included the editor of Charlie Hebdo. Following the massacre in Paris that claimed his life in 2015, we were advised to relocate from Harvard because of the ease with which we could be tracked down. After 12 years of teaching some of the history department’s most popular courses, I was reluctant to leave—all the more so when I was informed that the Stanford history department had no interest in offering me even a courtesy appointment, much less a joint one. But we had to move, and Hoover’s offer was in many other ways attractive.

I have always kept an open door to students, whether I am teaching or not. So, in May 2017 I accepted an invitation to meet a group of students associated with the Stanford Review and the College Republicans. Out of interactions over lunch, in meetings and exchanges of emails, I heard these students express their dissatisfaction with a campus dominated by liberal and progressive thought. From this came the idea, formulated by the students, of a “Stanford Speaker Series” to address the lack of political diversity and debate on campus. One student suggested inviting the political scientist Charles Murray as part of a conservative speaker series. However, I wanted to build bridges between Hoover and Stanford, and so I proposed a bipartisan program to model free speech and civil debate.

That fall quarter of 2017, I discussed the speaker series idea with Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne and Provost Persis Drell as well as then Hoover Director Tom Gilligan. They liked the idea. It was decided to proceed without delay in the 2017/18 academic year. They suggested that Michael McFaul, director of the Freeman Spogli Institute of International Relations and also a Hoover senior fellow, lead the initiative alongside me. A steering committee of students was put in place that included not only the originators of the program but also, at my suggestion, representatives of other student newspapers—the Daily and the newly founded Globe—for balance. The program was given a name: “Cardinal Conversations.” The steering committee approved the speakers to be invited. However, I did nearly all of the inviting as it required personal connections to persuade people to come at such short notice.

All participants were of the highest quality; some were controversial figures. In the first conversation, Reid Hoffman discussed politics and technology with Peter Thiel—perhaps the sole Donald Trump supporter in Silicon Valley. But to hear such voices was the whole idea of a free speech series. As the president and provost wrote in “Advancing Free Speech and Inclusion,” published on the “Notes from the Quad” website on November 7th, 2017:

…breakthroughs in understanding come not from considering a familiar, limited range of ideas, but from considering a broad range of ideas, including those we might find objectionable, and engaging in rigorous testing of them through analysis and debate… Our commitment to free expression means that we do not otherwise restrict speech in our community, including speech that some may find objectionable… It is imperative that as a university, we avoid a culture in which people feel pressured to conform to particular views. One way to encourage that is to ensure that diverse perspectives are actively discussed at Stanford.

So enthused was the leadership of the university with the concept that, when the story broke in the Stanford Daily on January 10th, 2018, the press office claimed the credit for it: “The provost and president were contemplating and discussing this for some time, and they asked Niall and Mike McFaul to co-lead,” Vice President for University Communications Lisa Lapin told the Daily.

The advertised and collectively approved speakers for February 22nd, 2018, included Charles Murray, in conversation with Stanford’s own Francis Fukuyama on the subject of populism. As the university leaders’ enthusiastic endorsements showed, Murray’s appearance was an entirely appropriate affirmation of what academic free speech must ultimately mean: the right to utter and hear views that in fact or perception run counter to the deeply held beliefs of the majority. Mike McFaul appeared to share this view, telling the Stanford Daily that he “look[ed] forward to helping to assemble an equally compelling set of conversations on international and foreign policy issues in the fall.”

However, Murray was also a target of left-wing opponents of free speech. At a notorious event in May 2017 at Middlebury College, his attempt to deliver a lecture had been terminated by a riot that had left the professor who was escorting him with whiplash. On January 30th, the Stanford Daily reported that a group of students had written to President Tessier-Lavigne to express their “disapproval” of Murray’s invitation, accusing him of using “pseudo-science to further racist ideas.” The vice-provost, Susie Brubaker-Cole, convened a meeting two weeks later with students opposed to Murray’s visit—not to Murray’s views (which they were perfectly entitled to oppose) but to his visit. Their leader—I shall call him Mr. O—said, as an accusation, that I was trying to “weaponize free speech.” Yet Brubaker-Cole and Mike McFaul conceded the demand of these opponents of free speech to be represented on the student steering committee for Cardinal Conversations.

The predictable consequence of this concession was an open letter to the university president and provost the next day, entitled “Take Back the Mic: Racists Are Not Welcome Here” and signed by eight student groups—the Chicano students, the Black Student Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Stanford Sanctuary Now, Who’s Teaching Us?, the Asian American Activist Committee, Students for the Liberation of All People, and the Stanford Democrats. The letter falsely accused Charles Murray of propagating an “oppressive, racist and meritless pseudo-science” and now explicitly demanded that his invitation be rescinded. At the meeting with the vice-provost, I had asked if any of those present had read any of Murray’s books. None had.

On February 15th, the president and provost, while defending their decision not to disinvite Murray, promised “more diverse speakers in the months ahead” and “even more ideologically diverse student representation on the organizing committee.” Then, on the day of the Murray-Fukuyama debate, Mike McFaul went to print in the Stanford Daily. Having approved all the invitations and given his public endorsement a month earlier, the co-leader of Cardinal Conversations now condemned Murray for ideas that “could inspire racist agendas and white nationalist movements.” To my consternation, he encouraged students either to protest or not to show up and stated that he would probably not be going himself if he were not involved in organizing Cardinal Conversations!

On the evening of the Murray-Fukuyama event, a noisy crowd chanted slogans outside the Hoover Institution. One likened Hoover to the Ku Klux Klan. Another featured the couplet “Fuck Steve Bannon / Fuck the Western canon!” Their leader Mr. O was quoted in the Daily the following day, again grossly defaming Charles Murray as a eugenicist responsible for “perpetuating white supremacy in the national discourse and in the local discourse.”

Unlike at Middlebury, the protesters did not succeed in derailing the event—thanks to tight security around Hoover. The two speakers delivered a stimulating discussion that made a nonsense of the wild allegations of racism. But the intentions of the opponents of Cardinal Conversations were by now perfectly clear, as was the reluctance on the part of the university administration to stand up to them. I felt a strong desire to help the students on the organizing committee who had originated the idea—and who had come to me for help in the first place—to resist the obvious plan to take over the committee and establish a veto over future programming.

Now for my own fault. As I have freely acknowledged, my desire to save Cardinal Conversation from a hostile takeover, combined with satisfaction that the Murray event had gone ahead, provoked me into some juvenile banter. When one of the student originators of the speaker series emailed me the following day in triumphant mode, I replied to him and others in the chain in the same vein. “A famous victory,” I wrote. “Now we turn to the more subtle game of grinding them down on the committee. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance.” And I added: “Some opposition research on Mr O. might also be worthwhile.”

I should, as I admitted at the time, have maintained greater detachment in what I wrote to students even in a jocular exchange. It was wrong and in poor taste—even as a jest in a private message to students who knew me personally and were familiar with my sense of humor—to suggest “some opposition research on Mr O.” But jest it was (the topic was much in the news at that time). Had I seriously intended some research to be done, I would either have received it or repeated the request. Yet it was never mentioned again. Instead, as all subsequent emails make clear, the only thing we discussed was how procedurally to approach the impending contest for control of the steering committee. On April 7th—at a meeting in which only students were involved—the radicals’ proposal was rejected and a new system of recruiting committee members adopted.

As luck would have it, however, my exchange of emails in the aftermath of the debate became an overlooked part of a longer chain on an unrelated subject and found its way to a wider group of undergraduates—including a number who were working for me as research assistants—one of whom sent it to the provost. I immediately offered to resign from “Cardinal Conversations.” My language had been inappropriate; it was likely to become public. The series fizzled out soon after, having lasted all of four months. The university made no serious attempt to follow through on its stated plan to hold Cardinal Conversations in the next academic year. The “imperative” of January had ceased to exist by May.

In private, a week later, the president and provost of the University had an apparently amicable lunch with me and urged me “not to give up on Stanford.” As that made clear, contrary to Professor Landy’s allegations, there were not the slightest grounds for any form of disciplinary action. Later that same day, however, the Daily published their story: “Leaked emails show Hoover academic conspiring with College Republicans to conduct ‘opposition research’ on student.” In contravention of its own “Policies and Standards,” the Daily had made no attempt to contact me before publication. Within hours of the article’s appearance, I was warned by a university press officer and hastily drafted a statement, but only a part of that was published by the Daily.

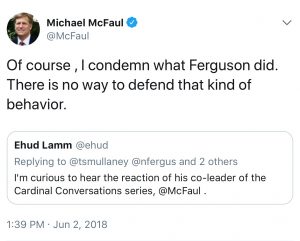

And so was born the idea, inflated with each successive republication by the New York Times, Vox, the Guardian and others, that there had been “harassment” and “bullying” and “snooping”; that I had “plotted” and “conspired.” The Stanford historian of China, Tom Mullaney, took to Twitter and claimed my conduct was “repulsive… a gross abuse of power.” Mike McFaul also

tweeted: “Of course, I condemn what Ferguson did. There is no way to defend that kind of behavior.” (He later deleted the tweet.) Later, the Stanford Daily accused me of “coordinating personal harassment” and “abusing [my] position of authority to encourage bullying.” The story grew with the telling. On February 8th, 2019, 15 professors published a “Statement on the Hoover Institution” in the Daily, in which they claimed that I had “urged… student allies to do ‘background checks’ on those holding differing views.”

The important point is not that I have been vitriolically criticized, with repeated omissions of my side of the story, in defiance of basic journalistic standards. The real significance of the Cardinal Conversations fiasco is broader. My efforts and motives in instigating Cardinal Conversations, in response to undergraduates’ requests, and in defending the program against the assault upon it were simply ignored. It is, of course, a basic principle of academic engagement that one must read sources critically, not rely on a single source, and put matters into context. No-one—not those who had collaborated in organizing Cardinal Conversations, and not a single one of the thousands of my academic colleagues and students over a career of three decades—came forward to put the few words of a private email into their appropriate context. With a single exception (a journalist who candidly conceded that Vox would not actually print a word of what I said), no-one spoke to me to obtain my side of the story before going into print with their allegations.

The ultimate casualty is, of course, not me but free speech. Once, universities represented the spaces of greatest intellectual freedom, openness, and diversity. Now, they are among the places in the Western world where the inhabitants—students and professors alike—are most inhibited about what they say aloud, as is clear from research by Heterodox Academy and Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. This is the result of fear—or of complicity in the imposition of a new and profoundly illiberal orthodoxy.

And so, an initiative that was supposed to model free speech, and had attracted stimulating speakers with varying viewpoints to one of America’s top educational institutions, was allowed to die. The students who opposed free speech were encouraged, deferred to, and never asked to respect the freedom of others. Charles Murray’s appearance at Stanford was a Pyrrhic victory. And, to cap it all, Stanford faculty members who are ideologically hostile to the Hoover Institution took—and continue to take—advantage of their academic privilege to repeat slanderous statements in a forum where I am not even represented.

I have worked hard for my students over the years, at Cambridge, Oxford, NYU, and Harvard, as well as at Stanford. On many occasions, I have gone beyond merely teaching them, grading their papers, and writing their reference letters. The idea that I would “conspire to conduct opposition research on an undergraduate” was absurd when it was first published in a student newspaper three years ago. It is high time this falsehood ceased to be reproduced in the Stanford Daily and repeated before the Faculty Senate.

If free speech at Stanford means only that a student newspaper and a minority of faculty members can libel Hoover fellows with impunity, it is a travesty. And if professors of comparative literature at Stanford regard this is an appropriate way to conduct themselves, small wonder public confidence in our universities is at such a low ebb.