Entertainment

The Videogame That Takes Us Inside the Hell of a Nazi-Run World

The New Order starts off in 1962, but not the 1962 we know. In this timeline, the Axis powers have conquered Eurasia, and are now seeking to bring Africa to heel, along with other far-flung corners of the world.

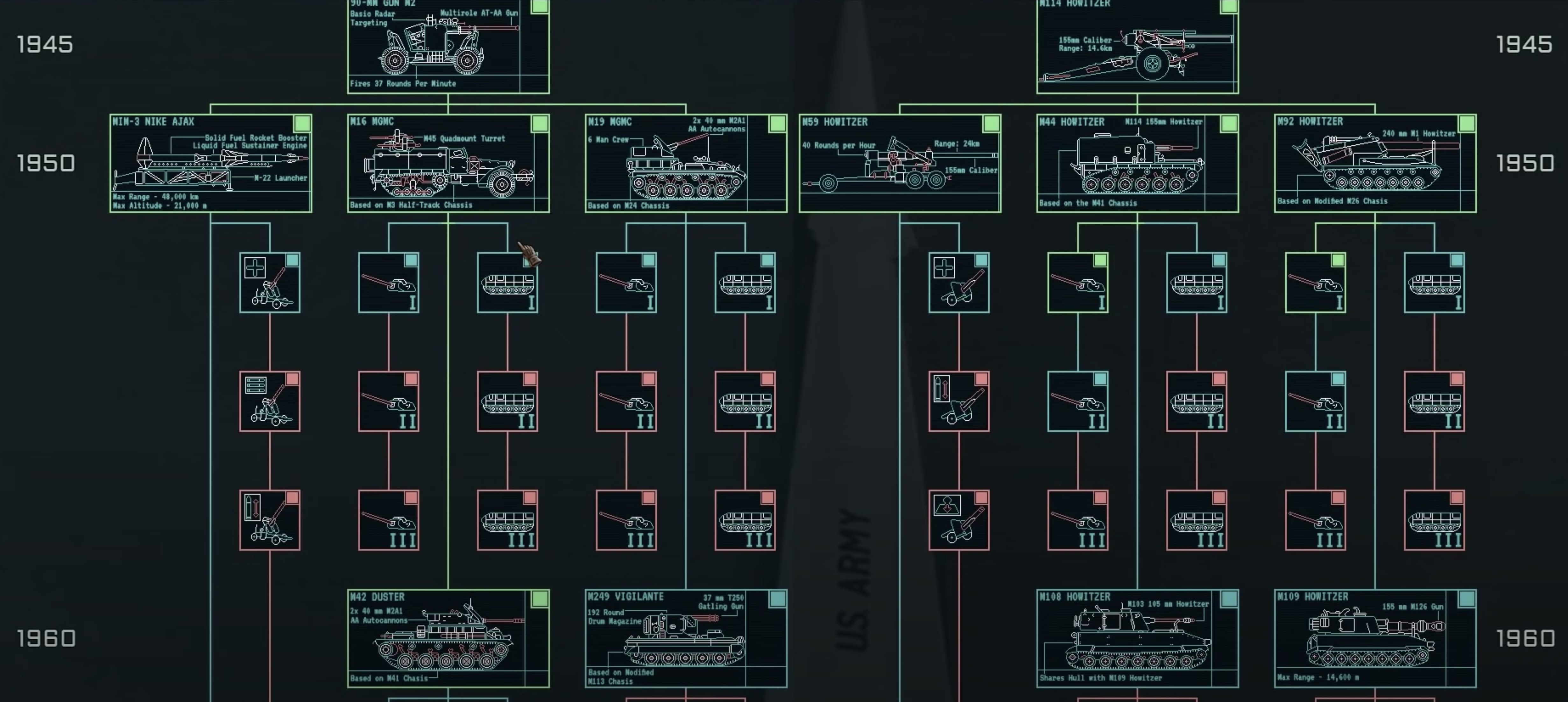

For almost 20 years, Hearts of Iron has been a prominent franchise in the videogame genre known as “grand strategy.” In these games, players don’t command individual characters or armies, but whole nations or even civilizations. In Hearts of Iron, which is now up to its fourth iteration, players lead nations and navigate them through (often fictional) conflicts, alliances, economics crises, and intrigues before and after World War II, exploring alternative historical narratives.

What’s more, Paradox Interactive, the developer of Hearts of Iron 4, designed the game in a way that allows gamers to create their own customized versions, often called “mods,” which take the game into radically different timelines. By one count, more than 20,000 mods are available for Hearts of Iron. These include some that fall into the category of “total conversion modifications”—mods that are so ambitious that they effectively create entirely new game systems. A notable example is The New Order: Last Days of Europe, a huge project that crowdsourced the efforts of hundreds of volunteer fans. Since its conception in 2014, the project was led by Jakob Zaborowski, 23, who recently stepped down from this role following the mod’s successful launch on the universal Steam gaming platform.

Zaborowski himself is a fascinating character. A young but accomplished American coder and digital story-teller, he now works a day job installing robots in hospitals and acting as a consultant for videogame companies. During his short working life, he’s found himself homeless at least twice (including one episode in which, according to his recounting, he was evicted by his roommate’s ex-fiancée after a bizarre disagreement that involved the wedding’s cancelation and a bunch of cats). Moreover, his Hearts of Iron project has caused him to be trolled viciously by pro-Nazi extremists who oppose The New Order’s depiction of a fictional Nazi-conquered world as a war-torn dystopia. In some cases, they’ve tried to smear Zaborowski as a pedophile, doxed him and his relatives, tried to get him fired from jobs, and even contacted an ageing relative to wish her dead (the relative had, in fact, died weeks earlier).

Other critics, on the Left, have become enraged by the game’s unflattering depiction of socialist dictatorships and formerly communist countries acting as Nazi quislings. But Zaborowski (who describes his own politics as “pretty liberal”) reports that his primary motivation for creating the mod was his opposition to so-called “wehrabooism” in the alternate-history and gaming community—a colloquial term that describes those who exhibit an unsettling fixation on the supposed prowess and competence of German personnel (even as these wehrabooists, in some cases, profess disdain for the underlying evil embedded in Nazi ideology). The reason The New Order is so successful (it has about 130,000 Steam subscribers) is that it communicates this message without feeling preachy.

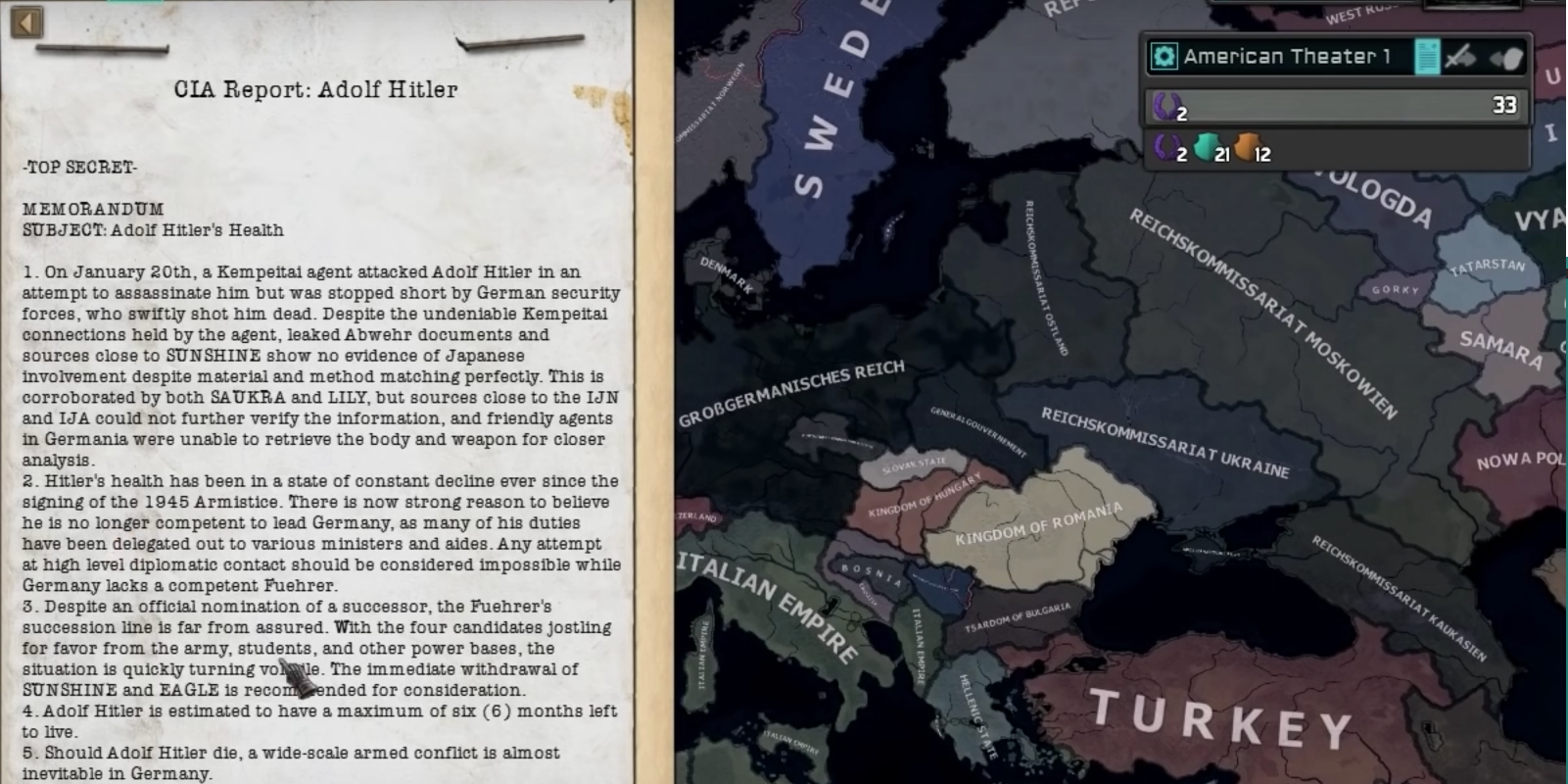

The New Order starts off in 1962, but not the 1962 we know. In this timeline, the Axis powers have conquered Eurasia, and are now seeking to bring Africa to heel, along with other far-flung corners of the world. But deep cracks have formed beneath the surface conceit of monolithic totalitarian rule. The Germans, Japanese, and Italians have broken away from one another as they pursue their own territorial ambitions, all the while dealing with restive populations within their existing empires. As an ageing and increasingly senile Hitler waits for a Nazi spacecraft to land on the moon, the entire system starts to crumble under the weight of its own inhuman despotism. This is by design, Zaborowski told Quillette, as he saw Nazism as a system so flawed that, even had it prevailed by conquest in World War II, “it never had a chance of surviving long term.”

As players of Hearts of Iron 4 will know, there is plenty of granular political detail that’s specific to each country. The American sub-plot, for instance, allows players to sway the electoral college to their preferred political faction. In the former USSR, players can launch scavenging runs on behalf of one of the myriad Russian warlords who rule the lands that German armies ravaged in the 1940s—such as the vengeful Black League of Omsk, Lazar Kaganovich’s Stalinist-inspired neo-USSR, the amoral technocracy envisioned by Andrei Zhdanov, or a new and horrific play on the idea of a Holy Russian Empire. (In this way, the dynamic somewhat mirrors the chaotic ethno-ideological fighting that followed World War I in Russia and neighboring areas, until Lenin prevailed in 1922.) Each faction and area progresses through the game according to its own unique set of incentives and geopolitical constraints. Most gambits end in tragedy and horror.

Unlike in old boardgames such as Risk or its videogame equivalents, the action isn’t dominated by giant blobs of armies roaming the board, painting the map one color or the other. Rather, it’s driven by events (many of which occur randomly) that call for players to respond through politics, bribery, or appeasement. What military combat takes place often assumes the form of theater-specific proxy battles, armed interventions, and civil wars.

In developing the game, Paradox deliberately chose a software structure that allowed mod creators to design narrative arcs without being required to do a lot of actual coding. At times, the game feels more like an exercise in choose-your-own-adventure storytelling than a conventional videogame. An event as minor as a shrimp-boat confrontation can set off a major conflict between the United States and Japan, while cinematic vignettes describing the cruel fate of English collaborators as they’re led off to execution can make a player thirst for vengeance.

The mod is undeniably “political,” as both fans and critics have argued. But the politics doesn’t have much to do with Nazism per se, whose inhuman nature is simply taken for granted. It’s more about how the course of history, combined with human nature and the lust for power, can create a nightmare world that, once conceived, is difficult to escape. As Zaborowski notes, many players come to the game expecting that they will step into the shoes of a liberal democrat and act as a force for good against evil. But the mechanics of the game are designed to show how difficult that can be, as players lapse into the strategic calculus of the-end-justifies-the-means.

“Players will think, ‘I won’t do bad things or I won’t attack people. I won’t invade countries.’ But then they start playing the mod and they start having to make these decisions. Like, okay, well, if I side with [US] segregationists [we can get conservatives on side to] beat down the Nazis harder, and that’ll be better for everybody, right? Or they’ll go, ‘Actually, you know, it might require burning down a whole nation and leaving a bunch of countries to die… But in four years, [we’ll prevail].’”

From slaves toiling in the Reich’s factories, to the industrialized wastelands of Manchukuo and Heinrich Himmler’s Burgundian fiefdom (which follows an unusually extreme form of Nazism), the mod doesn’t sugarcoat what the ramifications of an Axis triumph would have been. Many of the decisions involve the lesser of two (very, very evil) evils. In Africa, for instance, one may control Wolfgang Schneck, a former military pilot who attends recreational safaris by helicopter. He’s a stereotypical Nazi in some respects. Yet he’s not nearly as horrifying as neighboring warlord Hans Hüttig, a ruthless exterminationist who runs camps of African slaves in the fashion of King Leopold II’s Congo.

Meanwhile, Italy is dysfunctional, as Mussolini’s would-be successors attempt to claim his fascist legacy. In Japan, militarists and political hardliners with dreams of purifying Japanese society according to their own doctrines plot to upend the country’s imperial traditions. Everywhere, there is the stench of corruption, wanton cruelty, and incompetence—the furthest thing from the sleek, hyper-competent, Nietzschean übermensch of wehrabooist fantasy. (The closest one can come to that is an Albert Speer-led version of Germany with unsettling parallels to Deng Xiaoping’s China.)

Ultimately, though, this is still a game, and so the plotlines are full of lurid, fast-moving sublots that seem plucked from genre fiction. As Burgundy, you control how Himmler goes about destroying all traces of French and Belgian culture, while also possibly sparking a nuclear apocalypse that allows Aryans to build a new society on the ruins of the old. Life is cheap, and whole swathes of Europeans—rebellious Poles, once the German Civil War ends, for instance—hang in the balance of keystrokes. Or Germany can invade the United States and provoke World War III. Along the way, the gameplay shows that, while Nazism is singularly evil, its mass-murderous effects can be replicated by many other species of totalitarianism, left and right alike, on the same seven-, eight-, or even nine-figure body count.

At the same time, it is not impossible to create a politically happy ending. You could, for instance, succeed where Valery Sablin failed in real life, and bring about a genuinely humane version of the Soviet Union. Alternatively, a John Glenn presidency could inspire Americans to land a man on Mars. Even among the fascist victors, from Sōkichi Takagi’s drive to reform Japan, to the Reich’s “Gang of Four” working behind Speer’s back, there are characters seeking to make hell a little less hellish—even if their decisions are not necessarily idealistic. The game rejects a simplistic “good versus evil” dynamic, but the idea of human hope is not extinguished. And its presence adds to the dramatic tension that keeps people playing. “I’ve always subscribed to the idea of earning your happy ending [in a game like this],” Zaborowski told Quillette.

The New Order is still a work in progress, with the modding team exploring plans for further additions and changes. Till now, they have resisted critics who are suspicious of the game’s themes. But as I have written in Areo, the political tendencies in the gaming world are such that developers may be thinking twice about the injection of controversial motifs, especially in a climate that increasingly fixates on the ideological wrongthink of gamers. German activist Keinen Pixel den Faschisten (“No Pixels For Fascists”) has all but endorsed enforced censorship. In one viral 2019 YouTube video about “Socially Conscious Game Design,” posted by the popular Extra Credits channel, gamemakers were instructed not to “treat Nazis and terrorists like they are just one of several morally equivalent character skins for players to try on.” As critics have noted, the argument is analogous to the idea that playing violent videogames makes you more violent: i.e., that playing a game as a Nazi could turn you into an actual Nazi. (Zaborowski himself has mocked such commentary over the years.)

The New Order, as a case study, shows that such broad-brush warnings ring false. Indeed, it is hard to think of an immersive digital experience that does a better job showing just how horrible a Nazi world would be. Yes, there are popular games—such as Battlefield V’s single-player downloadable content revolving around a German tank crew toward the end of World War II—that put players into the shoes of German soldiers without giving them moral signposts that indicate the horrors of Nazism. But this isn’t one of them.

It’s often been said that modern narrative-driven videogames—including space operas such as Mass Effect, and single-person shooters such as S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl and Metro 2033—can straddle the line between art and amusement. But they can only be effective, in either capacity, if creatives such as Zaborowski have a free hand to immerse us in the worlds that exist in their imagination. And while the vision of human cruelty he and his co-creators offered in The New Order was dark, no historian can tell us it’s inaccurate.