Activism

Radicalized Antiracism on Campus—as Seen from the Computer Lab

The University of Washington, like most schools, tracks the performance of student groups as part of its effort to enhance diversity and reduce inequality.

The campus battle over what I’ve previously called the equity agenda has recently shifted almost completely from a focus on gender to a focus on race. This has been accompanied by a series of surreal spectacles at the University of Washington in Seattle, where I teach. In the aftermath of the George Floyd protests, student activists have made new demands upon the school’s administration, while scathingly denouncing anyone they perceive as dissenters.

Just consider our university president, Ana Mari Cauce—a Latina lesbian whose activist brother was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. One would imagine that she’d command a certain level of respect from even the most puritanical social-justice enthusiast. But there is little evidence of that: Student protestors have marked the campus with slogans such as “Anti Black Ana,” denounced her as a “Poo Poo Pee Pee Head,” and a “white woman” (a term of abuse, obviously).

The background to this is a petition containing seven demands put forward by the university’s Black Student Union, including a call to remove a statue of George Washington that’s been on campus since 1909. Protestors have installed “resistance art” at the base of the statue, painted it red, plastered it with posters, and left messages in chalk. At first, university staff attempted to clean the statue and remove the art, but eventually they just allowed it to accumulate. Very little came of the protest other than informing Cauce that they consider her a traitor for refusing to immediately submit to the petition’s demands.

As at many other institutions in the United States, the public focus of administrators has turned to the idea of antiracism. The highest-ranking diversity officers from our three campuses sent a joint email in late May with the title “Antiracism work is all of our work.” The authors explained that “We are united and unequivocal that antiracism must be at the core of all we do if we are to dismantle the destructive and oppressive effects of white privilege and systemic racism, which is the cornerstone of all U.S. social institutions, including our criminal justice system.” It was unclear whether they were merely pandering to the protestors, or whether this message signaled a serious institutional commitment to substantively overhaul existing policies. Either way, it seemed prudent to educate myself on the topic, and to consider whether I should make changes in my own courses at the university’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering.

I began by reading Ibram X. Kendi’s 2019 bestseller, How to Be an Antiracist, since this is the book so many people are talking about, and since my university’s antiracist messaging seems consistent with Kendi’s broad denunciations of American society.

Like most Americans—including me—Kendi wants to eliminate racial inequity. He writes that “Racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not standing on approximately equal footing.” By way of example, the author notes that “71 percent of White families lived in owner-occupied homes in 2014, compared to 45 percent of Latinx families and 41 percent of Black families.” Even conservatives would concede that these figures represent unequal outcomes.

Kendi mentions that he does not like to use phrases like “systemic racism” because he considers them vague. He prefers to zero in on the set of identifiably racist policies that, as he defines them, “produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups.” But he then proceeds to define these terms in a way that indicts pretty much the entirety of American society. By Kendi’s analysis, in fact, I am an unrepentant racist who has perpetuated racial inequity in every policy decision I have made in my career. So is everyone I know. I was hoping to find some middle ground where Kendi and I might meet. But I couldn’t.

* * *

Where racial inequities are concerned, there’s plenty of data for Kendi to consider in the field of computing. The Computing Research Association reports that blacks receiving computer-science PhDs, working in technical roles at prominent companies, and teaching computer science at universities represent less than two percent of personnel in these areas. The data show that the pipeline that produces professional computer scientists is producing very few black computer scientists.

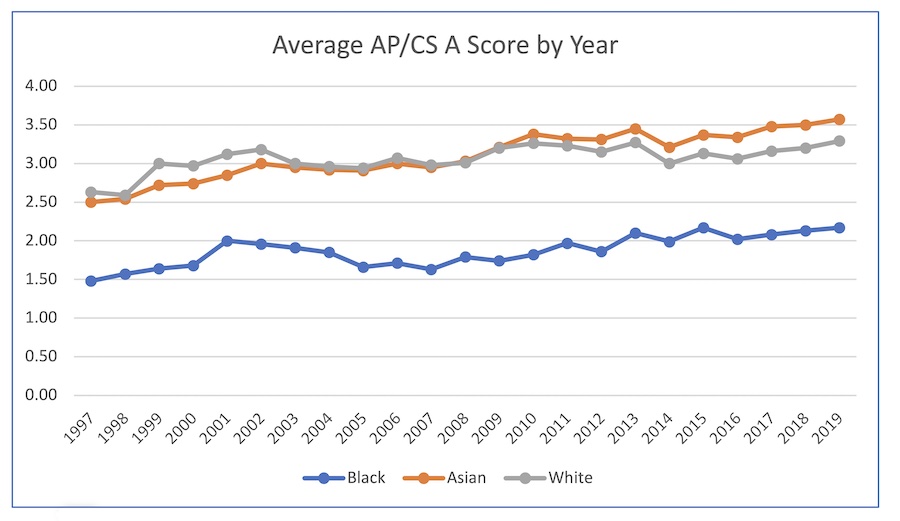

I am most familiar with the portion of this pipeline that involves introductory computer-science courses for undergraduates, sometimes described as CS1 and CS2. I have also been heavily involved in the Advanced Placement exam, known as AP/CS A, which is a College Board CS1 course similar to the one I teach at UW. I pulled data from the College Board to produce the following chart, showing the average score obtained on the AP/CS A exam, broken down according to self-reported racial identity. The exam is scored on a five-point scale, which can be thought of as roughly equivalent to the grades of A, B, C, D, and F. (Anything below three is considered a failing grade.)

During the 23-year period covered by the available data, black students have scored, on average, about a point below whites and Asians. Scores have been going up over time for all groups, but the gap has persisted. In 1997, the gap between black students and the white/Asian average was 1.09. It has since grown to 1.26, as of 2019. All of this is publicly available information.

By Kendi’s definition, AP/CS A is a racist test because it produces unequal outcomes. That makes me a racist because I regularly participate in the annual exam reading. In fact, I was the chief reader when the AP/CS A exam was introduced, which means that I decided how it should be graded and how raw scores should be converted into AP scores.

Is it possible that the course is the problem? I have been teaching a similar course for over 30 years, and have heard a litany of complaints, the most of common which can be paraphrased as follows:

- The focus on computer programming is too narrow, and will fail to motivate women and underrepresented minorities.

- Having students work individually on programming problems gives the wrong impression of computer science, and fails to expose students to the high degree of collaboration required in the field.

- Focusing on just programming does not allow students to explore the broad social implications of computing, including how different communities have been impacted by computers.

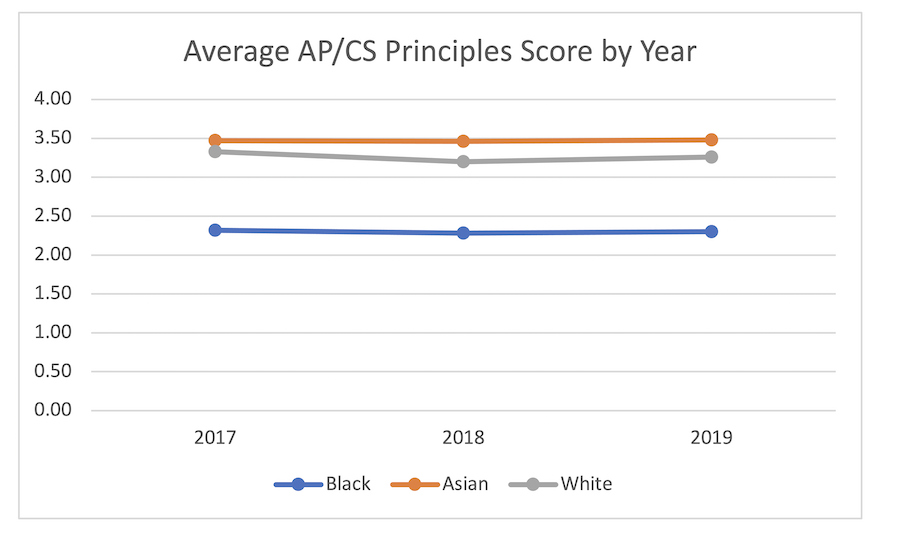

You might imagine that a different course, one that addressed these concerns, might help overcome the racial performance gap. But why just imagine? A group of computer-science educators has spent years trying to develop exactly such a course. The result is known as AP Computer Science Principles. In this course, programming is just one of several major topics. Other big ideas include creative development, and studying the impact of computing on society. Students work on projects in groups on topics that interest them.

Unfortunately, the results have been underwhelming. The percentage of black students taking the exam went up, but their average relative performance did not. We have just three years of exam data, but in each of those years, blacks scored, on average, a full point below the average for white and Asian students. In 2019, for instance, the scores averaged 2.3 for black students, 3.26 for white students, and 3.47 for Asian students.

The best minds in our field—and the ones eager to remedy the type of inequities that Kendi identifies—have failed to produce a course and exam that can close the performance gap. So what should we do instead? Both AP CS exams test mastery of programming skills and computer-science concepts. Students who fail to master these concepts will have difficulty creating or analyzing computer software. What is the alternative?

In some circles, there is a taboo against describing this kind of data—even though, as noted above, it is public information. But how can you solve a problem like racial inequality without measuring its effects? Kendi himself would seem to agree with this principle, at least in its broad form, or he would not have cited home-ownership data and similar statistics in his book.

But Kendi also writes that, “the idea of an achievement gap means there is a disparity in academic performance between groups of students; implicit in this idea is that academic achievement as measured by statistical instruments like test scores and dropout rates is the only form of academic ‘achievement.’” In other words, perhaps the black students are just as accomplished as their white and Asian counterparts, but the exam is misfiring as a measurement tool. In this case, the only real alternative would be to abandon testing altogether. And I worry that proponents of antiracist policies will soon be urging administrators to take this step.

Kendi might consider the elimination of tests—or, at least, this kind of test—as a win for black students, because they will no longer be collectively disadvantaged by what he sees as a racist exam. But in fact, we would be harming individual students, by denying them the opportunity to demonstrate their level of mastery. That includes the black students who receive high scores on these exams, and who can go on to pursue educational and professional opportunities on that basis.

On the other side of the country, these ideas are playing out in the debate about how Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia should admit students. TJ, as it is affectionately known, has consistently been ranked the top high school in the nation by US News & World Report. It has the most impressive high-school computer-science program that I know of. I have worked with TJ computer-science faculty for over 30 years. Admission to TJ is highly competitive, and is based mostly on the results of an anonymously scored exam. But as a Quillette author recently discussed, the Fairfax County School Board is proposing to replace the exam with a lottery system, and its justification for doing so is very much in line with Kendi’s argument. The perceived problem, as a recent news article reported, is that TJ’s “student population has remained mostly white and Asian.”

The TJ story is playing out in many other places. A technology magnet school in Seattle switched to a lottery system for admissions four years ago. Hundreds of colleges and universities dropped their SAT/ACT admissions requirement because of COVID-19, and are considering making the change permanent in order to address diversity concerns. Magnet schools in New York City are considering dropping their entrance exams. Several departments at my university are considering dropping the GRE as an admission requirement to graduate programs, under the same rationale.

The result will be that the competence-sorting function that once was the domain of admissions officials will now be kicked down the road to professors, who, in turn, will be pressured to maintain a racially balanced grade curve. Inevitably, employment recruiters will have to take on the sorting role, perhaps by administering the same kind of basic tests that schools are now shunning.

* * *

The University of Washington, like most schools, tracks the performance of student groups as part of its effort to enhance diversity and reduce inequality. And so I could produce detailed performance data broken down by race for our CS1 and CS2 courses. But friends have advised me that I would be censured for doing so. It is a sad commentary on the current state of affairs that publishing data is seen as a provocative act, but I agree with their assessment. Nevertheless, there are a few general trends that I can describe without creating a scandal.

When you spend 30 years teaching the same courses, as I have, you learn a bit about predictors of success. Some students seem to have a natural affinity for computer science, which is obviously an advantage. But I find that how hard you try tends to be at least as important. That is why, particularly in our CS1 course, we build in opportunities to raise one’s grade through increased effort.

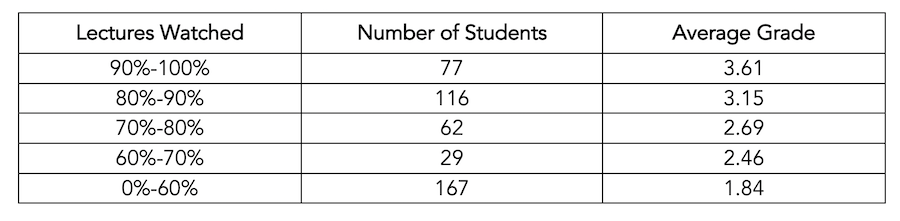

Because the pandemic forced us to switch to online teaching in the spring quarter, I was able to track how much time my students spent watching each of the lectures. Lecture-watching was highly correlated with course performance, as the table below attests.

Kendi insists that we look at outcomes. But his reliance on racism as the sole explanation for any disparities in those outcomes allows him to short-circuit the need for argument and proof. Most of us would agree that students who work harder generally get higher grades because the extra effort leads them to greater mastery of the material. And if it could be shown that students from some groups were spending more time, on average, than students from other groups, that would provide an alternative explanation for average differences in group performances. But according to Kendi’s logic, this is all just semantics, since we would be required to assume that the differences in lecture-watching rates are, themselves, an artifact of racism.

The UW Daily, a campus newspaper, weighed in on this issue in a column calling for “decolonizing of STEM departments,” which, they argue, “need to be less white and male.” The author called me out by name: “Reges is a perfect example of my concerns that STEM departments fail to properly educate students on diversity and identity when voices like Reges’ are components of them.” I gather that he thinks that, as a white man, I will fail to attract non-white students; and he is concerned that I don’t spend time discussing issues of identity related to computing.

Many of the critics who offer this kind of criticism seem far more interested in broad ideological claims than in the data that might serve to support—or refute—their arguments. The author is correct that we do see differences across racial groups on campus. The overall student population at UW is about four percent black, and black students represented about three percent of the students who enrolled in our CS1 course over the last year. But here’s an important detail: We didn’t turn away any black students. None. We had a policy of open enrollment. It’s one of those few contests in which resources are basically unlimited, and outcomes are determined by individual choices.

Should university officials make choices for our students? Should we force more black students to take the course—even though they don’t want to? Or should we prevent non-blacks from taking the class, in order to ensure a desired arithmetic balance? (One paradox here is that the Black Student Union petition demands, among other things, an enhanced profile for African Studies. If acted upon, this demand would likely serve to disproportionately draw more talented black students away from STEM, and thereby exacerbate the problem we’re supposed to be solving.)

Or perhaps we should follow the suggestion from the above-quoted UW Daily editorial, and modify the course so as to include more issues related to identity, ideally in a way that, over time, would attract a more diverse mix of students. But if so, we would need to address the biggest discrepancy, which happens to involve white students. They made up about 34 percent of the most recent freshmen class, but represented only about 21 percent of the students who enrolled in the CS1 course over the last year. Should we redesign the course to be more attractive to whites? What kind of content would that involve?

Clearly, when you give students the option to choose their area of focus, you’ll see different outcomes for different groups. As I wrote in my Quillette essay on why women tend to code less than men, “one should never attribute to oppression that which is adequately explained by free choice.” The groups that are most overrepresented in my department are Asian students (33 percent) and international students (35 percent), who mostly come from China. It’s not clear how this result can be attributed to white supremacy.

* * *

In university discussions, one increasingly hears the subject of race discussed in revolutionary, and even religious tones—with ideologues demanding that their peers declare themselves to be on the right side of history. I got a firsthand look at this in the spring of 2019, when I found myself surrounded by a mob of students while attending an “affirmative action bake sale” sponsored by the UW College Republicans. The crowd burst into laughter when I said that I don’t see rampant racism on campus.

But the fact is, I don’t. The University of Washington is one of the most progressive institutions on the planet. And while my opinions will be dismissed by some because of my white skin, I have seen almost no real racism in the 16 years during which I’ve served on admissions committees, attended faculty hiring meetings, trained and managed an army of TAs, and served on bodies that assign awards and scholarships. The few overtly racist incidents I have witnessed mostly involved discrimination in favor of women and minority students, even when it violated a Washington State law forbidding such preferential treatment. But none of this evidence is taken as persuasive—or even admissible—by those who see American society hopelessly contaminated by white racist hate.

Kendi weaves his life story into every chapter of his book, and he ends with a discussion of his personal battle with cancer. He draws the analogy that racism is a cancer destroying America. He says that he can’t tell them apart any longer, and he refuses to even try. It’s a perfect metaphor for an author seeking to create a sense of urgency, since cancer is not something that can be ignored. It typically requires drastic intervention. Those who ignore the call are trapped in denial, and will be held responsible for society’s descent into racist apocalypse.

But from what I have seen, racism is more like a chronic illness that never quite goes away, but which one can seek to manage—much like the illness I’ve had for over 30 years. Cancer patients typically are laser focused on their illness, and are willing to undergo extreme treatment, because the alternative is often death. Those who live with chronic illness, on the other hand, learn to focus on other aspects of life whenever possible. Kendi demands an end to racism in America, and he wants it now. He certainly deserves it, but the reality is that we can’t give him that. No country can. And so talking about it in the language of life-or-death apocalypse isn’t realistic or helpful.

Like cancer sufferers, those of us who live with chronic illness are familiar with a sense of being cheated. Kendi and I have that in common, I think. Why is this happening to me? How is that fair? It isn’t fair, but dwelling on that doesn’t get you anywhere. You have to learn how to live the best life available to you within those constraints.

Other black authors, including Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, Wilfred Reilly, John McWhorter, and Coleman Hughes, present a more traditional and hopeful narrative. They have not given up on Martin Luther King’s pursuit of a colorblind meritocracy, one in which his children would be judged by the content of their character and not by the color of their skin. They acknowledge that racism still exists in America, but they believe we have made significant progress, and that it is no longer a dominant factor in determining outcomes.

As I worked on this article I found myself jotting down notes in double-column form, to understand some of the differences between these two grand narratives—Kendi’s and King’s. Someone might be able to find a dialectical synthesis of these two narratives, but it eludes me. As far as I can tell, there is no middle ground to be found. The new antiracists see their mission as an existential struggle that requires revolutionary action and all-or-nothing moral judgments. (“We should eliminate the term ‘not racist’ from the human vocabulary,” Kendi argues. “We are either being racist or antiracist. Is that clear for you? There’s no such thing as ‘not racist.’”) Civil-rights traditionalists, on the other hand, recognize that the fight against racism must be accompanied by strategies aimed at tackling other problems, including crime, failing schools, family issues, and negative community influences.

On my own campus, meanwhile, I’m paying attention to the fate of the George Washington statue because I believe it helps indicate which side is winning. If one believes Kendi’s cancer-themed narrative, then it makes sense to obliterate the statue—much as one would cut out a cancerous tumor. But according to a more traditional view, the University of Washington community can find ways to get along, even under the shadow of a long-dead historical figure.

President Cauce has promised to form a task force to consider the university’s relationship to its namesake. For my own part, however, I’ve set my course. I will continue to use objective measures of student mastery, and will continue to encourage students to make their own choices, even if it leads to unequal outcomes on some diversity dean’s spreadsheet. And I am willing to discuss race with anyone on campus who wants to—though I warn that, as part of such a discussion, I will advance the proposition that maybe, just maybe, not everything around us has to do with the color of our skin.