Middle East

Saudi Arabia: The Pragmatic Case for Constructive Engagement

The ideology that inspired this insurrection hasn’t disappeared. Various kings have dealt with the fire of fundamentalism either through granting concessions or enacting purges.

There’s a compelling case that the US and UK should completely cut ties with one of the world’s most repressive regimes that institutionalizes the second-class status of women, outlaws any religion other than Islam and practices “kafala”—a system where migrant workers are relegated to a status that is often not much superior to slavery. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is a country that in the 21st century hosts public beheadings and crucifixions for “crimes” such as blasphemy, apostasy, and sorcery. Dissidents can be indefinitely imprisoned and are routinely tortured for even the most constructive of criticisms. It’s often argued that the West’s close relationship with the Kingdom makes a mockery of the freedom and democracy we claim to stand for.

When it became apparent that the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul was most likely ordered by Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) himself, Germany, Denmark, and Finland announced that they would cancel all exports of military equipment to the country. Other European nations such as Norway, the Netherlands, Austria, and Sweden suspended weapons sales in light of alleged Saudi war crimes in Yemen. Seven out of 10 parties in the UK Parliament (including the Labour opposition) are committed to the suspension of all future arms sales to Saudi Arabia. Last year in America, a series of bills that sought to block further arms deals won bipartisan majorities in the House and Senate but were vetoed by Trump. Presidential front-runner Joe Biden has likewise pledged to make the Saudis “the pariah that they are” and called for the cancellation of all weapons sales to the Kingdom. While well-intentioned, pursuing this path comes with an enormous cost.

The economic cost of cutting ties

Saudi Arabia’s immense wealth can primarily be put down to its oil which was discovered by the Standard Oil Company of California (now Chevron) in 1938 after it won a 60-year concession to explore the eastern side of the country. With the second largest oil reserves in the world, Saudi Arabia has offered access to its oil in return for American protection ever since. Sceptics of the relationship say this reliance is overblown. A rise in shale oil production over the last decade catapulted the US into the top spot for global oil production in 2018. That year Saudi oil represented only 9.1 percent of US oil imports, down from 11.8 percent in 2008. While it’s true that the US is the world’s largest oil producer, it’s also the world’s largest oil consumer. Twelve million barrels are produced per day but 20 million are consumed, meaning the need for overseas oil remains pressing. After Canada, the KSA is America’s second leading source of imported oil.

In today’s turbulent times where the collapse of Venezuela and sanctions on Iran have cut off options, maintaining a steady supply of oil is of paramount importance. What’s more, there are severe consequences to not keeping the Saudis on side. Turki Aldakhil, general manager of the Saudi-owned Al-Arabiya news channel, warned that if the US ever imposed sanctions “it will stab its own economy to death,” by causing oil prices to reach as high as $200 a barrel. The country’s centrality in the global economy cannot be underestimated. According to Caroline Bain, chief commodities economist at Capital Economics, “There is little doubt that Saudi Arabia has the ability to single-handedly engineer another ‘oil shock.’” When it comes to oil, China is Saudi’s biggest customer—not America. Despite this, all deals are still done in dollars. But severing ties could lead Riyadh to trade one of the most important commodities using the yuen. Ditching the dollar would radically devaluate it, undermining its status as the world’s main reserve currency, reducing Washington’s influence in global trade and weakening the purchasing power of ordinary Americans.

Ultimately, it’s Saudi Arabia’s appetite for arms that has a much more immediate impact. As the world’s largest weapons purchaser, between 2015-19 its major arms imports increased by 130 percent. Even during COVID-19, this demand didn’t drop. The USA is the primary provider of arms. Following in the footsteps of Nobel peace prize winner Obama who offered the Saudis military sales worth $115 billion, on Trump’s first foreign trip he visited the Kingdom and signed letters of intent that if concluded will be worth $110 billion immediately, potentially surpassing more than $300 billion over a decade.

It’s difficult to determine exactly how many jobs might be created. President Trump’s figure has fluctuated from 450,000 to as many as one million. Anti-arms trade activists claim it’s 20,000–40,000. An objective analysis that considers the multiplier effect of this specific military spending remains unavailable. What’s undeniable is the fact that defense contractors such as Boeing Co, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman account for about half of all defense exports to the Middle East and provide incredibly well remunerated work with excellent benefits.

After America, the UK is Saudi Arabia’s second largest weapons supplier. Here, the biggest business beneficiary is BAE Systems. In February 2014 Prince Charles donned Saudi dress and danced with a sword alongside the Kingdom’s royalty. The Janadriyah Festival where this event took place was sponsored by BAE which received an honor from the Crown Prince. One day after the dancing, the sale of 72 typhoon fighter jets was finalized.

Deals like these create opportunities for ordinary people. According to independent analysis, in 2018 alone BAE kept 124,000 Brits in work! As well as employing an army of engineers, scientists, technicians, and administrators, the company’s $3.6 billion in supply chain spending has spread wealth across the UK. Places with previously low levels of employment have benefitted most. In Barrow-in-Furness, a town in northern England, BAE brought over 7,500 full-time positions. Saudi Arabia is a customer that can’t be taken for granted. In 2017 a sixth of all BAE’s sales were to the Saudis and they were also the destination for 65 percent of all BAE’s international platforms and services sales (i.e., support services such as maintenance). In October that year, slowing demand for Typhoon fighter jets led to 2,000 job losses. To cancel orders would completely destroy livelihoods and local economies.

Arms sales are the tip of the iceberg. They’re a way to woo foreign direct investment. The Kingdom is home to many multi-billionaire private investors such as Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal who as well as co-owning the Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts group with Bill Gates, has major investments in American companies which include: Apple, Twitter, Citigroup, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, Coca-Cola, and the Ford Motor Company.

What’s more significant is Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) which is one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, managing an estimated $360 billion in assets. The good news for the world is ever since the Crown Prince became the fund’s chairman, as part of his 2030 vision to diversify the Saudi economy, he has shown a willingness to inject huge quantities of cash into other countries. Supplying the Saudis with arms persuades them to open this public purse. After Donald Trump’s $110 billion deal, they signed $200 billion in business deals with US firms. Similarly, when MBS came to London on a three-day trip, he finalized a multi-billion-pound order for 48 Typhoon jets which coincided with a commitment of up to £65 billion in fresh UK investments.

On the June 1st, 2016, the PIF sent Uber $3.5 billion in one single wire transfer. It now owns more than 10 percent of the company. MBS always bets on multiple horses. As well as a 5 percent stake in Tesla, the fund owns more than half the shares of Tesla rival Lucid Motors. When the UK’s NHS partnered with Babylon Healthcare Services, an app able to diagnose diseases more accurately than a doctor, it was thanks to Saudi funding that the initiative got off the ground. The Kingdom’s $45 billion check to SoftBank’s Vision Fund, the world’s largest tech-focused venture capital fund means Silicon Valley is awash with Saudi money.

In the wake of market weakness caused by coronavirus, the Saudis went on a spending spree, hoping to capitalize on historically low share prices. In May the PIF had multiple new investments, including: a $714 million stake in Boeing, $522 million in Citigroup and Facebook, and a further five million shares in Disney, valued at just under $500 million. In Britain, they bought $827.7 million worth of shares in energy giant BP, as well as a significant stake in BT—the country’s largest telecommunications provider. Cutting ties with the Kingdom, if it resulted in this type of money being taken out of American and British businesses, would have a catastrophic effect on employment levels.

In addition, the jobs directly put in jeopardy would be those of the approximately 35,000 American and 26,000 British expats who would lose their lucrative tax-free salaries.

Don’t care? If the West were to push for regime change or impose destabilizing sanctions, the poorest people in the world would suffer the most. Saudi Arabia is a magnet to 13.1 million migrant workers—the majority from the third world. In 2017 the country was the third-highest source of remittances, with workers sending $36.1 billion back to families across Asia and Africa. Economist Glen Weyl estimates that migration to the Gulf Cooperation Council countries has done dramatically more to reduce global inequality than all welfare states and transfers in the more egalitarian OECD countries combined. A stable Saudi Arabia is the reason millions have money to build a house, send their children to school or pay for lifesaving medical treatment.

The cost to security and stability

Cutting ties with KSA wouldn’t just make us less rich, it would make us less safe. Some say the opposite is the case. The writer Mehdi Hasan said, “Asking the Saudis to help lead the fight against terrorism is like asking the Mafia to help lead the fight against organized crime.” Osama Bin Laden was himself a Saudi national, as were 15 of the 19 9/11 hijackers. Moreover, the Saudi population contributed the second highest number of foreign fighters to ISIS in the world. Yet leaving aside the attitude and actions of those within the country, the Saudi state as an entity has a far more complex relationship with terrorism.

The situation was best summarized by securities studies professor Daniel Byman in his 2016 testimony before a House Committee investigation: “Much of Saudi ‘support’ for terrorism involves actors outside the Saudi government: the regime has at times supported, at times deliberately ignored, and at still other times cracked down on these actors. Some of these figures are important for regime legitimacy, and it is difficult for the regime to openly oppose them.”

During the Cold War, Saudi Arabia stood steadfastly against communism and its spread of Salafist Islam countered its influence. This came with American approval. As far back as the 1950s, the Eisenhower administration hoped to make King Saud (1954–1964) into a globally recognized Islamic leader and transform him into “the senior partner of the Arab team.” Billions were spent on charitable foundations and the construction of mega mosques around the world to spread fundamentalism. The Islamic University of Medina was established in 1961, eventually becoming a well-known recruitment center for jihadi fighters. Tolerating or sometimes even encouraging the more extreme elements was seen as a small price to pay for holding back the red tide.

But when the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union collapsed and such actors began to turn their ire towards America, the Saudi rulers were slow to respond. The Interior Minister in the 1990s, Nayef bin Abdulaziz (who later became Crown Prince) believed Bin Laden’s terrorist reputation was a product of US propaganda. After 9/11, he initially blamed the attacks on a “Zionist plot.”

Nevertheless, the 9/11 Commission, set up by President Bush to prepare a full and complete account of the circumstances surrounding the September 11th attacks, concluded that while “Saudi Arabia has been a problematic ally in combatting Islamic extremism,” it found no evidence the Saudi government or senior Saudi officials individually funded Al Qaeda.

What seemed like indifference and duplicity disappeared when between 2003–2006 Al Qaeda began a brutal bombing campaign inside Saudi Arabia itself, claiming over a hundred lives and injuring hundreds more. It started on May 12th, 2003 with homegrown suicide bombers simultaneously attacking three housing compounds in Riyadh. Saudi officials described this event as a “wake-up call” and “our September 11th” and began to take serious action against domestic terrorism and its support base.

The authorities arrested, imprisoned, and executed hundreds of suspects. By the spring of 2005, Saudi forces had either killed or incarcerated 24 out of 26 militants on the Kingdom’s most wanted list and issued a new list of 36 men. Multiple terrorist funding streams were stopped. For example, the Riyadh-based al-Haramain Islamic Foundation that at its height raised over $50 million a year in contributions worldwide was shut down due to ties with Al Qaeda. A series of laws were passed that made it much more difficult for Saudi citizens to move money internationally and put charities under greater state scrutiny. In July 2004 The Financial Action Taskforce, a global money laundering and terrorism financing watchdog, deemed the Kingdom to be “compliant or largely compliant” with international standards in almost every indicator of effectiveness. George Tenet, former CIA Director, reflected on such reforms in his memoirs: “The world is still not a safe place, but it is a safer place now because of the aggressive steps that the Saudis began to take.”

After the attacks in May 2003 that killed 39 people, including several Americans, Tenet travelled to the Kingdom to warn the royal family that they and their country were in serious danger. With American assistance, the Saudis built a modern security system which shared intelligence with the West. UK prime ministers across the political spectrum from Blair to Cameron have emphasized its critical importance. Theresa May claimed that the UK’s historic relationship with Saudi Arabia has potentially saved the lives of hundreds of Brits.

The most notable example was when the Saudi security services infiltrated Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and, using a network of informants, exposed a 2010 plot to send undetectable bombs in computer printer cartridges on-board a cargo plane. Though the package was destined for Jewish community centers in Chicago, investigators later found the device was viable and could have blown up the plane over Britain. It was thanks to a tip-off from the Saudis that the parcel was intercepted in England.

The man believed by British and American officials to be behind the attacks, Anwar Al-Awlaki, was also brought to justice courtesy of Saudi support. Despite being an American citizen, he’s alleged to have been a senior Al Qaeda recruiter and motivator, connected to at least a dozen terrorist plots in the US, UK, and Canada and a key leader of AQAP. Risking uproar from clerics about the presence of a non-Muslim military in the Holy Land, the Saudi rulers allowed the CIA to establish a secret airbase for unmanned drones within the Kingdom. This enabled intelligence operatives to pursue the “mission of hunting and killing ‘high-value targets’” who according to government lawyers posed a direct threat to the US. From the base, on the September 30th, 2011, missiles were launched into Yemen that took out Al-Awlaki.

The same strikes also killed Samir Khan, another American who proudly declared himself to be a “traitor” by becoming editor of AQAP’s magazine—Inspire. With English translations of Bin Laden’s speeches and how-to-guides for mowing down pedestrians, derailing trains and making homemade bombs, counterterrorism analyst Bruce Riedel described the publication as “clearly intended for the aspiring jihadist in the US or UK who may be the next Fort Hood murderer or Times Square bomber.”

The Saudis have also played a leading role in the fight against ISIS. When the group emerged, the Kingdom became one of the first Arab countries to join the US-led anti-Daesh coalition by launching several air strikes on targets in Syria. As well as building a 600-mile wall on the Iraqi border equipped with radars and infrared cameras, the Saudi authorities arrested more than 1,600 suspected Islamic State supporters in the Kingdom, foiled several attacks and offered to send ground troops to Syria.

While KSA is a nation with limited taxation infrastructure that makes it very tricky to track how much money citizens have and how they spend it, the aggressive action taken to tackle terrorist financing has made it much harder to send money to ISIS or similar groups. To avoid these countermeasures, in 2014 most money going to fighters in Syria was channeled via Kuwait. This is why US Treasury officials declared that the Saudis see “eye to eye” with the United States in stopping ISIS fundraising.

They’ve been on the front line in the battle for hearts and minds. Sheikh Abdulaziz al-Sheikh, the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, the country’s most senior religious authority, described ISIS as “enemy number one of Islam.” They’ve put their money where their mouth is. The mayhem that emerged when the group came on the scene was mitigated by a $500 million donation from Riyadh to UN humanitarian relief work in Iraq. A month later, they gave a further $100 million to the UN Office for Counter-Terrorism, making them the largest donor to this initiative that seeks to combat extremism across the world. An additional grant of the same amount was given to US-led reconstruction efforts in areas liberated from Islamic State in north-east Syria. By financing healthcare, agriculture, sanitation, transportation, electricity, education, and rubble removal, the Saudis have undoubtedly stabilized the region.

The Kingdom has worked to contain political Islam more generally. There are certainly counter-examples. In Sudan, KSA were the leading financiers of the National Islamic Front and in Syria it’s no secret that they’ve favored Sunni Islamists fighting under the umbrella of “The Army of Conquest.” Nevertheless, since the Saudi kings have presented themselves as “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques,” they’re extremely anxious that another movement may challenge their position as de-facto caliph of Islam, thus delegitimizing the regime. Ironically, despite imposing a hardline interpretation of sharia at home, they often support secularism abroad.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s contention that monarchies are incompatible with Islam makes the movement something of a Saudi nemesis. This wasn’t always the case. From the ’50s through to the ’70s, Saudi Arabia was a sanctuary for Brotherhood activists fleeing Syria and Egypt and the two parties were united by pro-Palestinian activism, as well as opposition to pan-Arab nationalism (particularly Nasserist thought). But the friendship always had friction. When the Brotherhood tried to set up a Saudi branch, King Faisal blocked it. He said, “All Saudis are Muslims and as such they do not need an organization to spread Islamic ideology.” The Gulf War was the final straw. The Brotherhood openly condemned the government’s decision to allow US troops on Saudi soil. By 2002 the interior minister described the organization as “the source of all evil in the Kingdom.”

Naturally, Riyadh was nervous about the Brotherhood’s rise to power during the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. Two years later, the Saudis were among the most enthusiastic supporters of the coup—bankrolling secular strongman El-Sisi to the tune of $4 billion. In 2014, Saudi Arabia designated the Muslim Brotherhood to be a terrorist organization. Meanwhile, senior Brotherhood leaders who’d escaped Egypt were granted refuge in Qatar—Saudi Arabia’s neighbor. Here they had a new base, as well as the airwaves of Al Jazeera, to spread their message across the region. In response, KSA, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt have blockaded Qatar. Since May 2017, they’ve severed ties, suspended trade and banned Qatar-registered airplanes and ships from utilizing their airspaces and sea routes. They’ve commanded Qatar to stop supporting groups classified as terrorist by the Arab states and by America. With this in mind, it’s safe to say the Saudis have suffocated the Muslim Brotherhood.

Under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, it was said that Iranians drank in public but prayed in private. Women wore miniskirts, youngsters danced at discos, and elected officials were free to pledge their oath of allegiance to the country without the Koran. Despite such divergence, KSA and Iran enjoyed relatively cordial relations. Both countries were among the five founders of OPEC. Animosity only arose after the 1979 Revolution when Ayatollah Khomeini decried the “illegitimacy” of the Saudi “puppets” of the US. To position himself as leader of the Muslim ummah, ridding Riyadh of its rulers became a top priority. His strategy? Isolate and surround Saudi Arabia.

With dreams of nuclear weapons, 523,000 active military personnel and proxy forces in Iraq, Bahrain, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, today the Islamic Republic is a regional superpower. Following the Iran-backed Houthi rebels’ 2014 capture of Yemen’s capital, a confidante of the supreme leader boasted, “three Arab capitals (Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad)… belong to the Iranian Islamic Revolution, and Sana’a is the fourth.” War-weary Brits and Americans are incredibly lucky that the Kingdom is willing to counter such belligerence. In Yemen they’re doing so militarily. In Iraq, they’re trying economically. After persuasion from the Trump administration, KSA opened a consulate facility in Baghdad in 2019—designed to facilitate travel and trade. They have something Tehran can’t compete with: a fatter wallet. They’ve invested $1 billion of loans for development projects, $500 million to boost Iraqi exports, and have even constructed a 100,000-seat soccer stadium in the country as a gesture of good will to the Iraqi people. Since much of southern Iraq relies on electricity from Iran, the Kingdom is working with Kuwait to explore ways to improve local infrastructure and meet this demand at a much lower cost. After America vacated Iraq, the young democracy with a Shi’a majority fell into Iran’s arms. Only the Saudis have the power to pull them away.

Iran is a repulsive regime that stones adulterers, allows child brides (as young as nine) and sponsors terrorism worldwide, but why is it any worse than Saudi Arabia? Why should the West favor one theocracy over another? For one thing, the attitudes and actions of the respective rulers are poles apart. Anti-Americanism (and anti-British sentiment) are built into the bones of the Islamic Republic. On the November 5th, 1978, rioters (incited by the mullahs) set fire to the British embassy in Tehran. After the revolution succeeded, 52 American diplomats and citizens were held hostage for 444 days—something commemorated by the annual Hate America Day. “Death to America” is the raison d’etre of the regime—a slogan chanted at mass rallies and during Friday prayers at every Iranian mosque.

This isn’t just rhetoric. In Iraq, they supply Shi’a militias with training and weapons to kill (among others) American and British troops. According to James F. Jeffrey, the former US ambassador to Iraq, “Up to a quarter of the American casualties and some of the more horrific incidents in which Americans were kidnapped… can be traced without doubt to these Iranian groups.” Earlier this year Iran attacked Iraq’s Al Asad Airbase, resulting in over 100 American servicemen being diagnosed with brain injuries. In April 2007, American forces in Afghanistan discovered that supplies of Iran-made weapons had been delivered to the Taliban—a discovery that, according to one State Department official, “sent shock waves through the system.” In August 2020, US intelligence found Iran offering bounties to Taliban fighters who target US troops.

The Saudis, on the other hand, have shown real friendship at times of great need. Even as early as WW2, they allowed the US to construct airfields inside the Kingdom. In the ’70s they persuaded President Sadat to expel 20,000 Soviet military advisors from Egypt. When Saddam’s forces invaded Kuwait in 1990, Saudi Arabia not only hosted coalition troops but committed approximately 100,000 of their own military personnel to the conflict—second only to the US. Along with the other Gulf states, they contributed £36 billion to cover the costs of the war. Despite vehemently disagreeing with the decision to invade Iraq in 2003, they still secretly allowed the US military to launch special operations from Saudi airbases and granted overflight rights to US planes. This year, in response to Iran’s alleged attack on Saudi oil facilities, they’ve paid $500m for the protection of 3,000 US troops. The late King Fahd’s words—“After Allah, we can count on the United States”—encapsulate a spirit of good will which the West would be foolish to squander.

Both Saudi Arabia and Iran stand accused of being tied to transnational terrorism. While Saudi support is mostly from independent actors, in Iran terrorist funding flows directly from the state. Authorities from Argentina to Bulgaria have traced the tracks of attacks back to Iran. Hezbollah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad have all had vast quantities of cash, as well as weapons and training to fulfil the Iranian regime’s apocalyptic dream—annihilating Israel. In complete contrast, the Saudis have softened their previous hostility towards the Jewish homeland. In 2015 Saudi and Israeli officials held a series of secret meetings which apparently went well. According to Israeli representative Shimon Shapira, “we discovered we have the same problems and same challenges and some of the same solutions.”

Of course, killing Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul is impossible to justify. However, it pales in comparison to how agents of the Islamic Republic recruit US citizens to commit atrocities on American soil. In 1980 Dawud Salahuddin, a convert to Islam, shot dead Ali Akbar Tabatabai—a leading Iranian dissident living in Maryland. Salahuddin reported that he’d received instructions from “someone in Washington… passing along instructions” from Tehran and been paid $5,000. He now lives in exile in Iran. Manssor Arbabsiar, a dual US and Iranian national, was arrested in September 2011 for trying to hire hitmen to blow up a restaurant where the Saudi ambassador would have been sitting. Attorney General Eric Holder explained that the plot was “directed and approved by elements of the Iranian government and, specifically, senior members of the Quds Force.” Similarly, in June 2017 British intelligence concluded Iran was behind a cyberattack on Parliament that hacked the emails of around 90 representatives—including the prime minister.

While weakening the Iranian regime and empowering its organized opposition would be positive, in Saudi Arabia it would be catastrophic. After the 2017–18 protest wave in Iran, 15 high profile dissidents (some in jail or exile) issued a statement calling for a popular referendum to secure a peaceful transition to secular parliamentary democracy. Such calls have been repeated several times since. For a population that has for decades lived under secular law, this is likely to be highly appealing. After all, the country is awash with wine and there’s a radical decline in Iranians even identifying with Islam—making an “Islamic” republic impossible to sustain. An official survey from 2000 found 75 percent of all Iranians didn’t say their prayers. By 2009, half the country’s mosques had become inactive. Recent years have revealed what has been described as a “tsunami of atheism,” a return to Zoroastrianism (the country’s ancient faith) and today it’s witnessing the highest rate of Christianization in the world.

KSA has its fair share of underground free-thinkers, feminists, and human rights activists. Nevertheless, demands for a freer and more open society are drowned out by those who want the world’s most Islamic fundamentalist state to become even more fundamentalist. When ISIS emerged, significant sections of Saudi society expressed sympathy. In July 2014, the Saudi-owned Al-Hayat newspaper released an opinion poll claiming that an astounding 92 percent of respondents believed the Islamic State “conforms to the values of Islam and Islamic law.” There’s reason to believe that toppling the mullahs in Tehran would lead to liberal democracy but replacing the Saudi rulers would create something far more extreme than the regime.

Given how the future of the Middle East is intertwined with the fate of us all, remaining neutral in the struggle between the two preeminent powers is impossible. Saudi Arabia makes for a natural ally, one which values our security and maintains regional stability. Though the country has an arsonist past, fairly recent reforms have transformed the Kingdom into the firefighter of the War on Terror.

The cost to humanity

The war in Yemen has taken the lives of approximately 100,000 people and displaced a further 3.5 million. Since 2015 Saudi Arabia has blockaded Yemen, already the poorest Arab nation, creating severe shortages of food, medical supplies, and aid. Yemen is suffering from the largest cholera outbreak in recorded history and the largest food security emergency in the world. An estimated 2.2 million children are acutely malnourished, including almost 360,000 children under the age of five who are struggling to survive. The UN considers the country “one step away from famine.” Is this simply the price we pay so our own people can have well-paid work and sleep safely at night? If cutting ties with Saudi Arabia would stop the extreme suffering and starvation in Yemen then whatever hit our economies and our security would take, it would be worth it. But it wouldn’t so we shouldn’t.

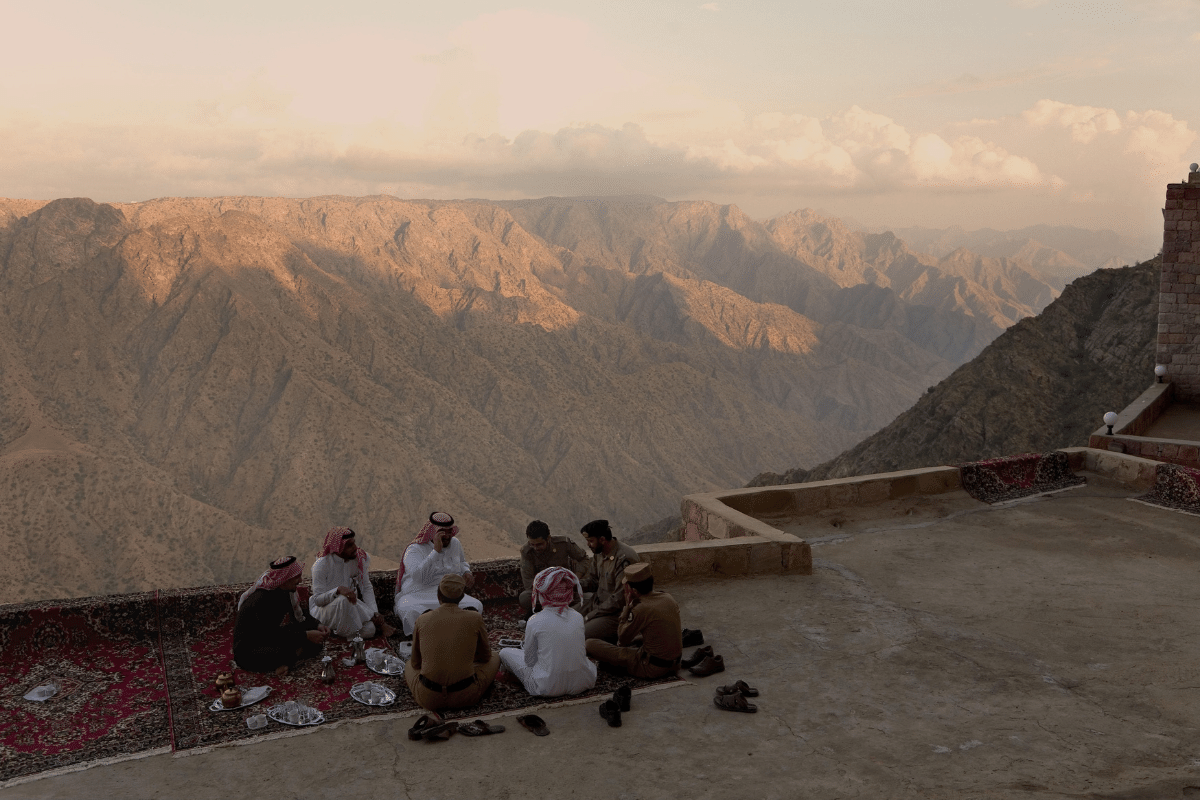

There’s a lot of noise about the actions of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen (many of which are indefensible). But the international media has been somewhat silent about who started the conflict. In September 2014 the Houthis, a militia rooted in Zaidi Shi’a Islam (a minority sect in Yemen), stormed the country. Marching down from their northern mountain stronghold around the town of Saada, they seized Sana’a (the capital), dissolved parliament and placed President Hadi under house arrest. Thankfully for him, he managed to flee to Riyadh where he convinced the rulers to form a coalition of countries to oust the Houthis and restore order. Given that his government is UN-recognized, international law allows for the Saudi intervention—specifically UN Security Council Resolution 2216.

For the Kingdom to answer such a call from their friend is understandable, particularly when you consider how in 2009 the Houthis killed a Saudi border guard, injured 11 others, and even annexed the Jabal al-Dukhan region on the Saudi border. This isn’t a ragtag group. They have extremely advanced weaponry. In 2013, photos released by the Yemeni government revealed the US Navy and Yemen’s security forces seized a class of shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles not publicly known to have been out of state control.

Despite Iran’s denial, in April 2016 the US Navy intercepted a large Iranian arms shipment, seizing thousands of weapons, including AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. The Pentagon say the shipment was bound for Yemen. Similarly, a study presented to the UN in 2018 concluded that a drone that had been flown from Yemen into Saudi Arabia was “virtually identical” to an Ababil-T drone made by Iranian aircraft manufacturers. KSA simply can’t be expected to tolerate an Iranian satellite state on its doorstep. Already, it’s a stepping stone towards Khomeini’s dream of bringing down the House of Saud. The Houthis are launching ballistic missiles over the border, targeting oil fields, cities, and even the Saudi royal palace.

The Houthi slogan “God is Great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse on the Jews, Victory to Islam” highlights the anti-Western hatred at the heart of the movement. President Hadi, on the other hand, was a friend to the US and UK. In his first meeting with British Foreign Secretary William Hague, he said: “We intend to confront terrorism with full force and whatever the matter we will pursue it to the very last hiding place.” It would be wrong to characterize Hadi as an out-and-out despot—he governed alongside an advisory multi-party parliament and a prime minister drawn from the opposition. Furthermore, his regime was reforming. In January 2014, it was announced that fresh elections would be held after a referendum on a new constitution. This progressive direction was disrupted by the takeover.

Under Houthi rule, Yemenis live under a reign of terror. Citizens are regularly rounded up and money is extorted out of their families for their release. The most sadistic forms of torture are common occurrences. Being doused with acid, hung up by the genitals, and beaten to the point of becoming paralyzed are all testimonies of former detainees at the hands of the Houthis. While both sides have shamefully used child soldiers, 72 percent have been Houthi.

The burden of the blame is placed on Saudi Arabia for blockading a country which imports 90 percent of its food. However, this was intended to stop the smuggling of weapons—not to increase starvation. Moreover, much of the suffering stems from Houthi landmines. Between 2016 and 2018, the Yemeni army cleared 300,000 landmines, many of which were laid on farms and grazing lands, killing and crippling local farmers and destroying food production. They’ve been placed in wells so now even drawing water is dangerous. Mines make it impossible for aid groups to travel throughout the country, denying the desperately hungry and sick Yemeni people food and healthcare. The UN claim the majority (60 percent) of civilian casualties are caused by coalition air strikes. However, since the Houthis have used civilian sites for military purposes, it seems likely that maximizing the civilian death toll is a deliberate strategy to undermine the coalition’s international credibility.

We must ask ourselves: what would happen if either side gave up their weapons? If the official Yemeni government gave up, there would undoubtedly be more killing and carnage in Yemen itself. Moreover, drunk on victory and given their history, the Houthis would likely take the fight to Saudi Arabia. They could potentially link up with the sizeable Shi’a community of the Kingdom’s eastern province, perhaps sparking a Shi’a-Sunni world war. Alternatively, if the Houthis went home, President Hadi would return with his reform agenda. The blockade would be lifted and there’d be a free flow of trade and aid.

If the West cancels weapons sales, the Saudis will simply shop elsewhere. In response to Obama’s Iran deal, Riyadh announced it would acquire S-400 missile systems from Russia and in 2018 alone they spent $40 million on Chinese weapons. The two major arms-manufacturing powers are positioning themselves as an alternative who will do business with no strings attached. They made a particular point not to condemn the killing of Khashoggi. China has a specific philosophy of “business only and business first” and “not interfering in other states’ internal affairs.” Translation: You can do whatever you want within your borders and we won’t ask any questions. There are numerous arms trade treaties which the US and UK have signed that bar the export of ballistic missiles, as well as certain cruise missiles and armed drones. The other great powers face no such constraints.

The UK has been described by ministers as having one of the most robust arms export control regimes in the world. Each prospective export is assessed according to the specific nature of each item, its propensity for misuse and the specific track record of its intended end-user. Similarly, when Prime Minister Theresa May met the Crown Prince, they agreed to “full and unfettered humanitarian and commercial access” to Yemen. Since the start of the conflict, the UK has given Yemen £930 million in aid. Experts have been deployed to provide reassurance that weapons are not being transported in the ships to ensure that food, fuel and medicine gets through Yemen’s Red Sea ports. Would Russia and China have these humanitarian concerns?

Having a seat at the Saudi table not only enables the protection of Western interests but the projection of Western values. For some, such a claim is disingenuous. After all, if the US and UK care about extending human rights, why have a close relationship with such a dictatorship at all? Why not push for democracy? The complexity of the Kingdom, which is built on a fragile equilibrium, explains why this wouldn’t be possible.

Saudi Arabia is a country of contradictions, one where the forces of 21st century consumer-capitalism vie with religious fanaticism, bent on dragging the society back to the 7th century. Women can be seen wearing burkas while worshipping the latest luxury brands. Everything comes to a standstill for the call to prayer five times a day but the financial sector isn’t required to adhere to Islamic banking practices. The strange society we see today stems from an 18th century alliance. Preacher Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab led a movement to popularize a literalist interpretation of Islam. While his message was at odds with mainstream Islamic scholarship at the time for being extreme, it gained traction by aligning with tribal leader Muhammad ibn-Saud. Together, their conquests would form what is now the largest state in the Arabian Peninsula.

Describing KSA as an absolute monarchy isn’t totally true—it’s a coalition, where the physical descendants of ibn Saud and the philosophical descendants of Wahhab maintain an uneasy balance of power. The Al Saud royal family manages the economy, foreign policy and the armed forces while the Wahhabi remit is justice, education, and social policy. The clerical cultural hegemony, exercised through control over the mosques and schools, enables them to push utter poison on the population. Tenth grade textbooks present The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a book that inspired the Holocaust, to be an authentic document. Preachers spew hatred of non-Muslims and the “wrong types” of Muslims (such as Shi’a and Sufi) from the pulpit. Weaned on Wahhabism from a young age, it’s highly unlikely that a popular uprising would transform Saudi Arabia into an Arab Switzerland.

In fact, in November 1979 there was an attempted revolution professing the opposite aims. Militants seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca, calling for the overthrow of the royal family and the establishment of a caliphate. After a bloody battle, the uprising was finally crushed only with the help of French forces. Sixty-three of the captured militants were beheaded in public squares across the country.

The ideology that inspired this insurrection hasn’t disappeared. Various kings have dealt with the fire of fundamentalism either through granting concessions or enacting purges. After 1979 more power was passed to the clerics, giving Saudi society what has been described as an “overdose of religion.” King Khalid tried to redirect the religious zeal of Saudi militants by encouraging them to fight for fundamentalist causes in external conflicts. But this came with consequences. After burying Soviet communism in the mountains of Afghanistan, the chickens came home to roost. The very fighters who’d been trained by the regime (such as Bin Laden) returned triumphant and sought to bridge the gap between what the country is and what it claims to be (an Islamic state). Alternatively, King Abdullah tackled the worst Wahhabis by banning them from preaching. This is risky as they could incite followers to revolt against the regime. Saudi Arabia is a pressure cooker: removing the royal family would be like removing the lid.

Modernization can only come from the monarchy. Their susceptibility to Western influence means that cutting ties would be deeply damaging to the cause of making Saudi Arabia a better place. In 1945 when FDR first met King Abdulaziz on board the USS Quincy (an American cruiser), the issue of slavery was raised. In 1962 JFK finally persuaded King Faisal to abolish slavery. Almost everything positive has come from the top down. The king traditionally meets the country’s religious leaders, the ulema, every week to discuss the direction of policy. The clerical class have resisted allowing radio, television, and girls’ education, viewing them as ungodly. Such staples of modernity are only permitted today because various kings have had the courage to fight to get them through. But in doing so, they risk alienating their own population. Prince Abdul Muhsin, the former governor of Medina, summarized the situation: “We have to have one foot here and one foot there and be a good acrobat.”

A Saudi ruler that completely abandoned its clerical allies would be ideal but would it be possible? It would be an extremely difficult and dangerous task, risking the eruption of a holy war within the Holy Land. In June 2017, 31-year-old Mohammed Bin Salman was appointed Crown Prince. Months before his ascendancy, he signaled that the influence of the clergy would be an obstacle to economic growth. He told the country’s clerics that the deal struck with them by the royal family was to be renegotiated. Such rhetoric has been followed up with real action.

The notorious mutaween, the religious police, who would patrol the streets enforcing the sharia rules on dress code, the mixing of men and women, observance of prayer, etc. have been completely stripped of their powers to arrest. MBS has taken back control of criminal justice in a variety of other ways. Flogging has been abolished—something the Saudi supreme court said was to “bring the kingdom into line with international human rights norms against corporal punishment.” This year, the death penalty was eliminated for those convicted of crimes committed while they were minors.

Saudi women are perhaps the biggest beneficiaries of the new changes. Women can now not only drive, they can open businesses and obtain a passport to travel abroad without permission of a male guardian. Other developments include: the first Saudi sports stadium to admit women, the first female head of the Saudi stock exchange, and the first Saudi public concerts by a female singer. No doubt there’ll be more to come. As the Kingdom tries to find foreign investors and now seeks to attract tourists, the country will have to have even more of a makeover.

There’s no getting away from the fact that MBS is a brutal dictator. But his efforts nonetheless constitute the average Saudi’s best hope for one day experiencing freedom. Despite his many mistakes, he’s dragging KSA, kicking and screaming into the 21st century. Though the means may be questionable to say the least, it’s still a noble cause. Rather than cutting ties, the West should offer critical and constructive support.

This can be achieved through utilizing our levers of influence. With a strong US military presence and over 7,000 Brits (some working for the RAF, some for the civil service, and others for BAE) overseeing operations, the West has multiple points of contact with the Saudi armed forces. This is very significant given the key role that an enlightened military often plays in the process of democratization. In the ’70s, it was General Gutiérrez-Mellado who led Spain’s transition to democracy after the death of Franco. In 2004 General Juan Emilio Cheyre brought the Pinochet era to a close in Chile. The West also has considerable power in shaping the police. According to the British College of Policing, which trains top Saudi officers, “Respect for human rights and dignity is interwoven into the programs.” A US criminal justice program targeted at Saudi law enforcement follows a curriculum based on American constitutional law.

Increasing numbers of Saudi students are choosing to study abroad. There are approximately 15,000 in the UK and 60,000 in the US. In 2005, as a way to repair the diplomatic damage of 9/11 and to tackle skill shortages, the King Abdullah Scholarship Program was launched—one of the world’s largest scholarship programs. The fees for most Saudi student are completely covered by the state. Not only has this injected a lot of money into local economies and helped American colleges overcome their budget deficits but it’s likely to influence the future direction of Saudi society.

Spending an average of five years in a democracy where young Saudis can (for the first time) think and speak freely has a profound impact on their psyche. While it’s true that 70–80 percent report spending their free time with other Saudis, even this has its benefits. In a foreign land, with limited English language ability, Sunni and Shi’a students come together in a way which would be unheard of back home. A great number of Saudi men feel passionately that this has been the greatest impact of the scholarship program as a whole. One respondent recalled, “Before… we do not know Shiite and they don’t know us. We do not listen to them and they don’t listen to us. We are afraid of them and they are afraid of us. But here we know many students who are Shiite and they are like brothers.”

In their home country, men and women (aside from relatives) have almost no interaction with one another. Public places are strictly segregated. But in America, Saudis attend co-ed classes and experience a society where women are able to fully participate. Female students (who make up over 25 percent of scholarships) report feeling a great sense of empowerment. Not having to cover their hair and having the right to wear whatever they want is an exhilarating experience for women who’ve grown up in such a stifling society.

Graduates from the program bring their new-found love for freedom back home. In 1990 Aisha Alama organized a protest against the driving ban on women. It was only after studying in the US that she said she realized that she was “a human being equal to anyone else. I am a free soul, and I am my own driver.” How could it possibly be that thousands of others don’t come to question the restrictions on their freedoms? Ultimately, since two-thirds of the population are under the age of 29, it’s the Saudi youth who will take their society forward. Through universities, the West has the opportunity to shape KSA’s best and brightest minds into the future reformers. For the US and UK to turn away is to turn off the light at the end of the tunnel.

Conclusion

Overthrowing dictatorships can create the conditions for freedom to flourish, as it did in Germany and Japan after WW2. Nevertheless, specific circumstances concerning security and culture sometimes make this impossible to achieve immediately. South Korea and Taiwan were American allies but were led by incredibly brutal dictators to begin with. Surrounded by a sea of communism and with the constant threat of annexation, it would have been unrealistic and unwise to demand a rapid transition to democracy. Instead, by leveraging aid and maintaining military ties, the US had the power to positively shape the direction of both nations. Today, these countries rival Europe and North America in their level of prosperity and the quality of their fully functioning liberal democracies. Evolution from within rather than revolution from below is the best path for KSA to pursue.

As well as sending most of its engineers and economists to train in the West, Taiwan’s local elections in the 1950s were the first step along the rocky road out of tyranny. The same step has been taken in Saudi Arabia. In 2015, King Abdullah granted women the right to vote and to run for seats in municipal councils. Reem Asaad, a female financial advisor tweeted, “Voted! For the first time in my adult public life in #SaudiArabia. You may find this laughable but hey, it’s a start. #saudiwomenvote.” The pace of change may sometimes seem slow but the liberties (however limited) that Saudi citizens are starting to enjoy shouldn’t be seen as inconsequential.

Praising progress when it takes place shouldn’t mean making excuses. Eventually, once the Saudi population is significantly enlightened, even more pressure can be applied. In 1984 Henry Liu, a Taiwanese journalist, was assassinated by KMT agents in San Francisco. His crime? Writing an unflattering biography of the then Premier Chiang Ching-kuo. At this point, President Reagan decided that Taiwan was ready for full democracy. In 1986, after holding hearings on Taiwanese democracy and travelling to Taiwan to observe elections, the US Congress called on the country to lift martial law. Some Congress members tried to make arms sales contingent on democratic reforms. Decades down the line, there’s no reason why a similar liberalisation of the regime couldn’t occur in Saudi Arabia.

As the custodian of Mecca and Medina continues to clamp down on the worst clerics, shifts towards secularism and dabbles with democracy, it will have ramifications across the Muslim world. Just as the British Empire led the transatlantic slave trade but then became its biggest adversary, Saudi Arabia has shown that it can atone for its arsonist past. With the West, they can work towards a world where the type of terrorism brought to public attention since 9/11 can finally be cast onto the ash heap of history.