Memoir

Guilt Trip: A Son's Memoir

I had been heartless about her pain. She had absorbed my selfishness without complaint, never once calling me out about it.

The Southern Tier of New York State is a bleak place in the dead of winter. The days are dark and short. Snow is piled high on the sides of the two-lane roads that connect towns like Olean, Wellsville, and Hornell, where I was born. You can drive for miles, past farms and houses standing alone, and see no one. In December 1968, I returned home for the Christmas break after my first semester as a sophomore transfer student at Reed College, in Portland, Oregon. I took a bus from New York City after the night flight from the west coast; it moved westward on Route 17, through the grey wooded hills, the freezing air deadening the smell of stale cigarette smoke and diesel fuel whenever the door opened.

I had not yet settled in at Reed, had yet to feel any strong spark of intellectual curiosity or ambition. I moved through my classes as a ghost. No professor had any impression of me, as I almost never spoke in the small seminar classes. I was shy, but what was worse, I had nothing to say. The famous humanities courses mystified me, offering no foothold, no way in, and I did nothing about it. The college was in a state of political chaos, with the Black students and others demanding a Black Studies program. Half of the sophomore class reportedly dropped out that year, typically freaking out from drug use or unable to deal with their courses, or some combination of those. I was living in a basement room of a student house. During a hard rainstorm, water had covered the floor, then froze. As the bus drew near the hamlet of Andover, where I would get off, it seemed as if I did not fit in to my life.

My family’s home was in the countryside, several miles from Alfred, then a college town of about 1,000 inhabitants; my father taught ceramic art at Alfred University. In the evenings, he and my mother sat reading books with titles like Irrational Man and The Way of Zen. There had never been a television set in the house. In high school, I would often stand looking out the large window that faced out across the valley. Car lights could be briefly seen on the highway below, and sometimes coming up the hill on our road. When cars turned into our long driveway, the lights would jump out across the field, and with them my heart, in anticipation of being picked up by a friend.

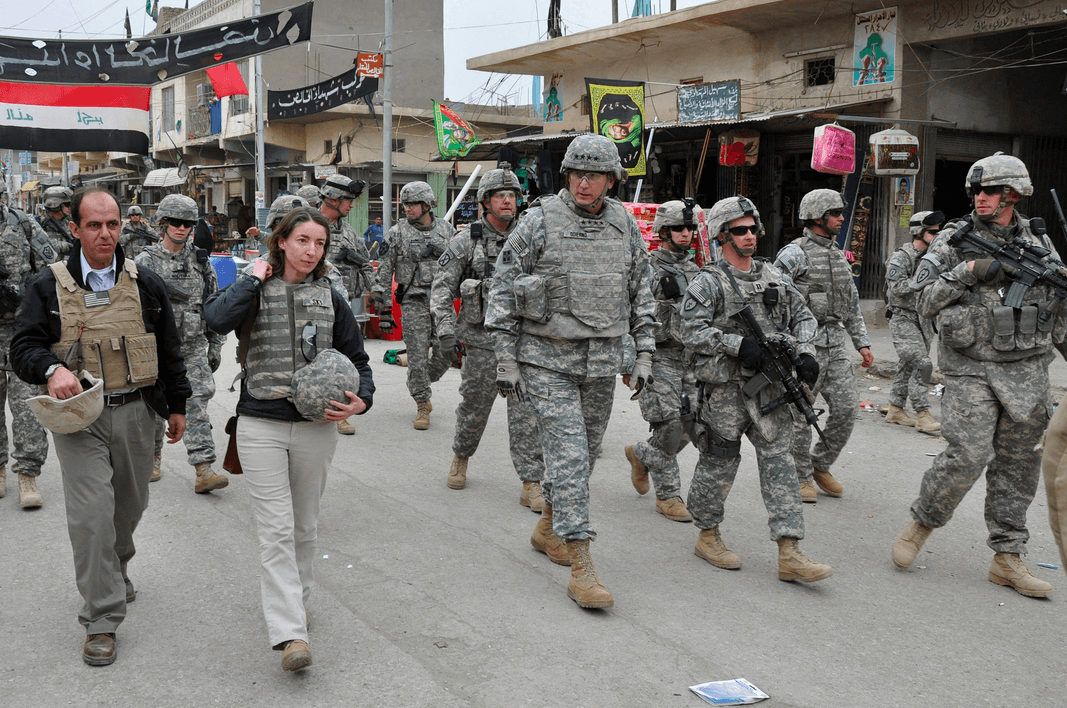

Daniel Rhodes, the author’s father, teaching ceramics in 1943, at a Japanese internment camp

Even though my sister and I had left home, the Christmas routine was the same as always—a mixture of happy rituals, animated and joke-filled talk, and painful nostalgia and pathos. I do not remember anything unusual happening, but there was a raw feeling. My time in Portland had seemed to strip off a layer of emotional crust, a crust that had prevented me from knowing something about myself. It had to do with my mother.

My mother, Lillyan Jacobs Rhodes, was born in 1915 into an unhappy Jewish family in Des Moines, Iowa. Her father, Leon Jacobs, came from a German Jewish family. The depression destroyed his small hat and grocery business.

A 1930s-era painting by Lillyan Jacobs

She had been pulled out of her university studies in 1933, after one semester, to work in his store, and never finished college. Her own mother, Pearl, née Anselberg, came from a family of recent immigrants from Romania, people who spoke Yiddish. Pearl was the brains in the family, but frustrated and difficult. My mother had been an artistic prodigy. Beginning in high school, she won numerous awards for her oil paintings. At 24, she was invited to send some to the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

She never mentioned these things to my sister and me.

In her teens, my mother contracted polio, which left her with a number of interconnected problems, not affecting her appearance but causing almost constant pain. Other physical ailments and accidents further complicated her health status. My father had also been a successful Iowa painter in the 1930s. When they married, she introduced him to American Indian pottery, launching his career in ceramics, but hers seemed to go sideways. She continued with art, but poured most of her energy into working along with him on his pottery, sculpture, and books.

She was restless, always reacting to what was going on around her, and often making judgments. She was never neutral, never in a state of rest or withdrawal. Her eyes, behind thick lenses, seemed anxious. She was never on the periphery of a conversation, but often the one driving it, sometimes with provocative statements.

She laughed heartily at dirty jokes I brought home from school. She was often insensitive and socially awkward, but she was also extremely kind, and took many young people under her wing. In the family, she nagged, goaded. She was never satisfied, and even after both my sister and I had eventually been awarded PhDs, she denounced the degrees as “shallow.” She once complained that my interests were “too cerebral.” My sister called her verbally irresponsible. In the insular, gossipy college town of Alfred, her style stood out. She often offended others, and often took offense. She was on edge, and put others there, too.

Her pain and suffering were almost omnipresent, ruining occasions that would otherwise have been happy. It intruded on trips, visits, outings, and parties. It isolated her from other people. But she rarely complained, and often said, when asked about her problems, “I’m OK.” I resented my mother’s pain as a child, and I have a horrific memory: One time, when I was about 10, she had collapsed and was weeping in her bedroom. Hearing the sounds, I felt a demonic grin come over my face, which I could not make go away. It filled me with shame.

Pearl, my grandmother, had died some months before, and I had inherited her old car, a black 1956 Chevrolet. I was going to drive it back to Portland after New Year’s. My mood had been low when I arrived, and had been sinking further; I was surrounded by some vague dread. Then, the day before I was to leave, I was driving the car with my mother sitting next to me. She was chatting volubly; I was silent. It was about four in the afternoon, and getting dark; the grey trees were fading into the darkening white of the snow.

I suddenly thought that here was a person who had loved me without condition; who had given birth to me despite a doctor’s warning that she would never walk again; someone whose affections I had pushed away and whom I had countless times disrespected. I had been heartless about her pain. She had absorbed my selfishness without complaint, never once calling me out about it. I felt a lump form in my throat and I began to freeze up. My responses narrowed, becoming perfunctory. Everything seemed pitiful, and everything about myself worthless.

I could not speak about my feelings to either of my parents. I would not have known where to start. I left the next morning, a sleeping bag in the back seat of the car. Just to get to the Ohio Turnpike took four or five hours on the slush-filled Route 17. I sat like a brittle statue behind the wheel, not daring to turn on the radio for fear of hearing sentimental music that would push me over the edge. In the darkness, I drove on to the western border of Ohio.

The next day, I wanted to make up for my slow start. I had snacks in the car, and stopped only for gas and the restroom. My mood was about the same. I was still frozen, still paralyzed, my guilt sitting heavily on top of my chest. I kept pushing on, eventually into Nebraska.

I was still driving at two in the morning. A fog had settled over the empty highway. I was off the four-lane Route 80, and onto old Route 30. I would have to find somewhere to sleep, but I was afraid to stop, afraid of silence and my terrible thoughts. My heart began to beat faster. The snowflakes poured over the windshield of the Chevy as it crawled along at about 30 miles per hour, floating through the fog.

I saw a sign that said “Ogallala 5 Miles.” I considered where I could stop and sleep again in the car. I passed darkened buildings; hardly a light could be seen. I drove on, and then another sign appeared, “Ogallala 10 Miles.” I felt myself panic, realizing I had lost my orientation. Had I somehow gotten turned around? It made no sense. Which direction was I going? I could not trust myself. I pulled into a deserted gas station and turned off the engine. I crawled into the back seat and covered myself with the sleeping bag. The constricting weight of guilt that had been pressing against me was replaced by terror that I was losing my mind. Maybe I would freeze to death in the night. I did not care.

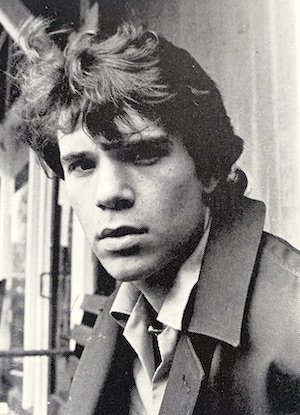

The author, in a 1971 yearbook photo

Around seven in the morning, I heard a sound and sat up. A man was nearby. I asked him which direction was west, and started driving again. I remember nothing about the rest of the journey to Portland. In January, there were no classes at Reed, as it was reserved for “independent study.” The atmosphere around the campus was even more anomic than usual. I was largely unable to speak to anyone, but hovered on the periphery of groups like a rag doll, vulnerable, without will, without personality. I paid a visit to a kindly dean who counseled students with mental problems. I had the feeling that, as compared to the psychotic episodes with which he was confronted, my case was not critical. At one point, I was with other students in someone’s apartment listening to jazz. A friend was there, a few years older than me, a person whose confidence and ease in the world felt like a rock. I blurted out to him that I could not speak. He acted as if it were nothing special, and when he left the party, he said cheerfully to me, “Well, I hope you learn to… communicate again.”

The symptoms gradually lifted and finally disappeared. Things improved at school.

But my relationship with my mother returned to the old patterns, and in the years that followed was often difficult. Throughout most of my 20s, my life remained unsettled. When I visited, my parents heard much of my difficulties in graduate school, my problems in the job market, and my confusion about what I wanted to do. My harsh treatment of my mother, and her insensitive behavior, persisted.

In 1986, she contracted lung cancer that was detected only after it had become inoperable. By then, she and my father had moved to California. I visited several times during her last months, and one time, which she felt might be the last, she asked me to speak to her. She said we should try to say what we needed to say to one another. We sat together on her bed, but said almost nothing. Later, when she was slipping in and out of a coma, she whispered to me, “I want to go out tonight.” She was trying to die. She asked me to give her a huge dose of morphine. Despite having no water or supplemental oxygen, she lived for several more days.

The day she died, my father and sister laughed when I said we could all relax now that she wasn’t around to tell us what we should be doing. But I was deeply troubled for months after her death, feeling that I had wronged her. My sister was spending a term at a university in southern California. She called and wanted to tell me a story.

One night, she had accompanied her house-mate to a séance. The “medium” had never met my sister before, and did not know her name. But during the session, she asked if there was someone in the group with a name very much like my sister’s. She came forward. The medium said that someone close to her was suffering. And she had a message for that person: “I’m OK.”

Aaron Anthony Rhodes is an international human-rights advocate, and president of the Forum for Religious Freedom-Europe. He lives in Hamburg, Germany with his family. He is the author of The Debasement of Human Rights: How Politics Sabotage the Ideal of Freedom.

Featured Image: Lillyan Jacobs Rhodes, photographed in the 1970s.