Cultural Nationalism

The Great Awokening and the Second American Revolution

The past is raked over for imperfections as left-modernist ideologues render the most grievance-based interpretation of history imaginable.

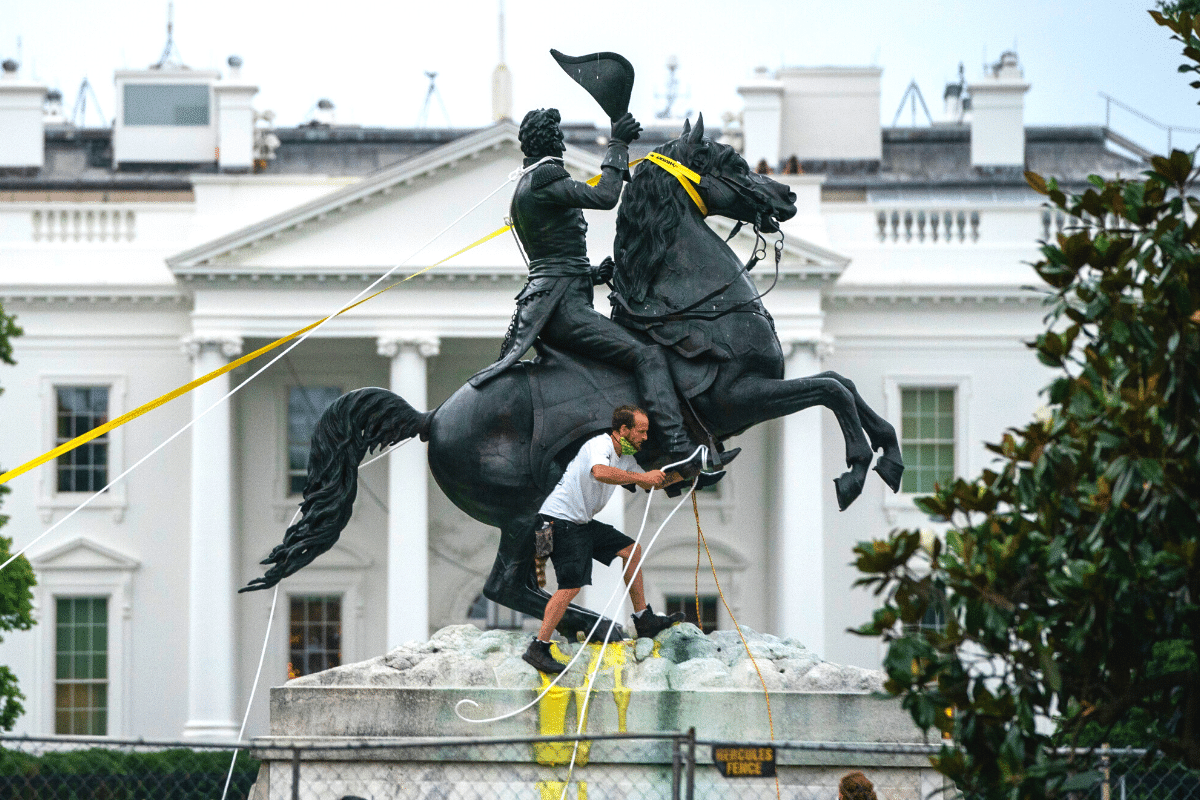

Statues toppled, buildings renamed, curricula “decolonized,” staff fired. The protests following George Floyd’s killing have emboldened cultural revolutionaries in America and Europe. The iconoclasts are changing minds, and could be in a position to enact a root-and-branch reconstruction of America into something completely unrecognizable to its present-day inhabitants. Imagine a country whose collective memory has been upended, with a new constitution, anthem, and flag, its name changed from the sinful “America” to something less tainted. Far-fetched? Not according to data I have collected on what liberal white Americans actually believe. Only a renewed American cultural nationalism can resist it.

According to multiple surveys, the effect of the riots which occurred at around the same time as the BLM protests is quite different from what occurred with previous waves of rioting. First, many of the participants in the major riots were white. Second, there has been no clear call for Nixonian law and order following the riots, but rather greater public acceptance of the BLM movement’s unsupported claims that contemporary structural racism explains why police shoot unarmed black men or violent crime plagues inner-city neighbourhoods. While 57 percent of Americans disagree with the protestors’ radical slogan, “defund the police,” an astounding 29 percent support it. This is so despite the deaths of a number of black people during the riots and the fact the riots have coincided with a steep rise in the number of black homicide deaths in inner-city neighbourhoods due to a “Ferguson Effect” of police reducing their presence in these areas.

Meanwhile Trump is polling well down after the riots, having dropped 2.5 points to Biden since Floyd’s death on May 25th. Trump’s repeated mistruths, unstatesmanlike behaviour and nepotistic employment of family members may have eroded the truth-based environment to such an extent that evidence-free shifts in issue position become increasingly easy. His sinking popularity tarnishes issue positions associated with his presidency, even when they are backed by the weight of evidence—as with the idea that indiscriminate police brutality rather than racism accounts for violence against unarmed blacks. The power of corporate and celebrity endorsement, magnified by “trendy” social media herding, has resulted in unusually high approval among whites for the activities of the rioters. This is an important departure from what occurred during, for example, the late 60s race riots, 1992 Rodney King riots, or even the 2014 Ferguson riots.

Statues, memory, and the social construction of harm

Progressive scholars are fond of emphasizing the socially-constructed nature of perceived reality. This is overstated, of course. Human minds are not blank slates. Gender can’t be readily reconstructed to make males dominate the caring professions and females the majority of ditch-diggers. Similarly, Americans can’t easily be convinced they are actually Russians.

But you don’t need to follow social construction to its postmodernist extreme to acknowledge that social construction does play a role in how we perceive the world. To a partial extent, there really is a “social construction of reality,” as Berger and Luckmann put it. Psychological research, for example, shows that flagging certain issues repeatedly, or framing them in particular ways, affects attitudes and feelings.

What society chooses to focus on and care about, the emotions it feels, the objects it sacralizes, the boundaries between groups, vary a lot across time and place. For instance, choosing not to shake someone’s hand is offensive in Western culture, but not in Japan, where a bow is the common greeting. Leaving food on one’s plate is treated as an insult in Japan, but not in the West. Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning show that in Western elite culture in 1800, as in violent inner-city neighborhoods today, insults were treated as violence, which can only be avenged by physical violence. But for most of us, who haven’t been inculcated into a touchy honor culture, verbal slights don’t carry the same emotional punch. We either ignore them or respond with a counter-insult. As the sociology of emotions tells us, the way societies and individuals emotionally respond to words is, to an important degree, socially constructed.

Let’s apply this lens to the sacred values of left-modernist ideology. Is a white woman wearing a Chinese prom dress complimenting or insulting the Chinese? Most Chinese would probably take the former view, but a left-modernist ideological entrepreneur can spin this as cultural appropriation and white colonialism. In effect, the left-modernist socially constructs “harm” and “racism,” spinning something positive into a negative and seeking to sensitize Chinese people to the “fact” that they should feel insulted rather than proud. Those inducted into the religion of antiracismget the message and signal their virtue online, helping to propel people toward the new norm. If this were to catch on in China, the emotions Chinese feel when seeing the image of a white woman in a cheongsam would flip from pride to anger.

The same sensitizing dynamic works for history, literature, film, statues, and even words. Like Red Guards with a hair-trigger sensitivity for sniffing out the bourgeois, today’s left-modernist offense archaeologists outdo each other in trying to reframe the world as racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist, and so on. Turning the principle of charity on its head, they insist on the most suspicious interpretation of a person’s motives when the subject matter is associated with their canonical totems of race, gender, sexuality. A Hispanic man flicking his fingers outside his truck window gets fired because this was photographed, tweeted, and spun as the “OK” white power sign. The result is an atmosphere where inter-personal trust is as low as humanly possible while discursive power flows to the accuser. The new cultural revolutionaries have constructed our emotional and conceptual reality.

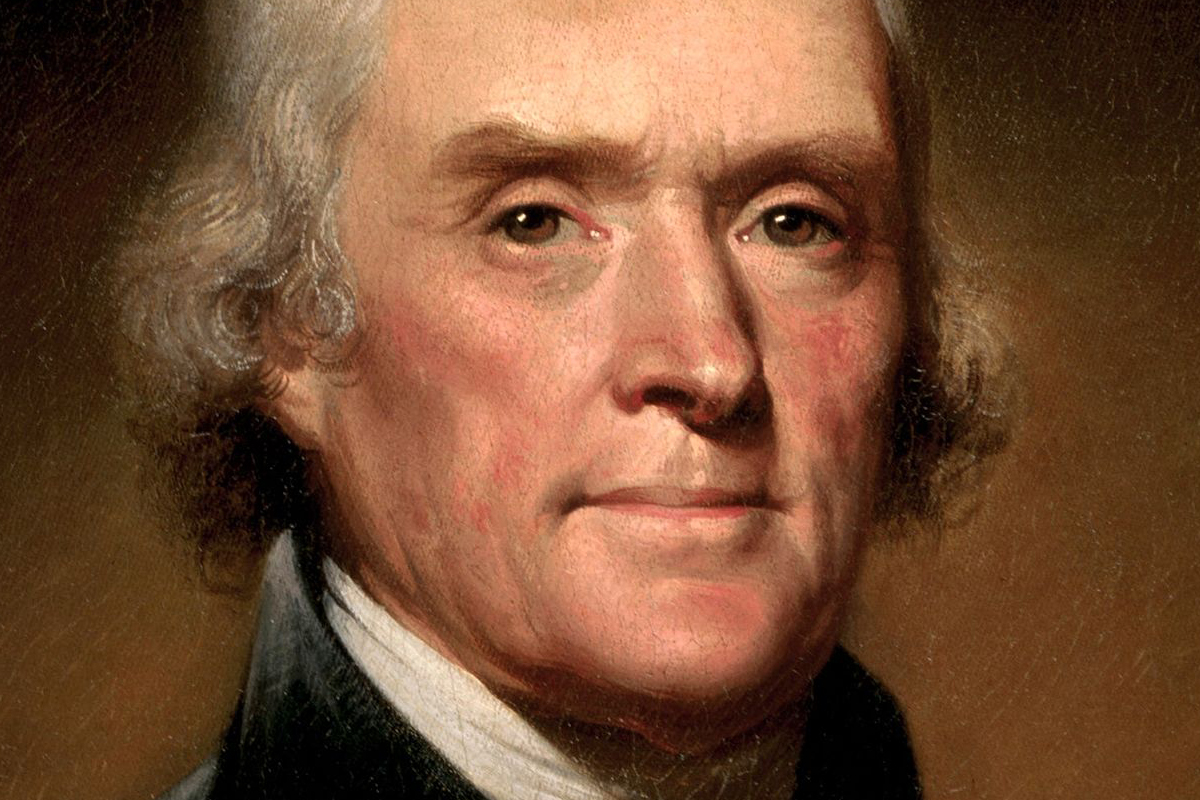

Once “harm”, “racism” and other concepts become unmoored from reality, more of the world is remade. Statues which were long ignored become offensive. Complex historical figures like Jefferson or Churchill, who embodied the prejudices of their time, or elites like Columbus or Ulysses Grant, whose achievements had both positive and negative effects, are viewed through a totalizing Maoist lens which collapses shades of grey into black and white. If a historic personage transgressed left-modernist sacred values, their positives instantly evaporate and activists myopically focus on their transgressions.

Suddenly, an entire Orwellian world opens up: place names, history books, statues, buildings. When you’re equipped with the anti-racist hammer, everything begins to look like a nail. In this brave new world, it doesn’t matter whether a symbol like the Rhodes Scholarship has acquired a completely different meaning, or whether a statue has become a symbol of something completely different. All must be levelled to bring forth utopia.

What has occurred across the West, especially in the English-speaking world, is a steady left-modernist march through the institutions. Beginning in the 1960s, former radicals entered universities and the media, capturing the meaning-producing machines of society. Once boomers became the establishment in the 1990s, the ethos of institutions started to shift. For good and ill, equality and diversity rose up the priority list. As these ideas filtered through Schools of Education and into the K-12 curriculum, older ideas of patriotism faded and the new critical theory perspective began to replace it. Sixty three percent of millennials (aged 22–37) now agree that “America is a racist country,” nearly half say it is “more racist than other countries” and 60 percent that it is a sexist country. Older generations are less radical, but 40–50 percent of boomers and Gen Xers agree with these statements, reflecting the long march of the New Left through American culture.

The deculturation of America

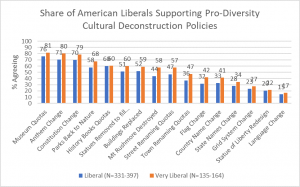

In order to find out how willing liberal Americans are to jettison the country’s cultural identity, I decided, on May 7th, to ask what I thought were outlandish questions—almost to the point of inflicting a Sokal Squared-style hoax on survey respondents. The answers I received amazed me. I then repeated the exercise on June 15th, after the George Floyd killing and subsequent protests to see whether things had gotten even crazier. It turns out they have.

After the preface, “To what extent do you think that the following should be done to address structural barriers to race and gender equality in America,” I presented 16 statements that an amalgamated sample of 870 American respondents could agree or disagree with. The sample is not representative of the American population—I used the Amazon Mechanical Turk and Prolific Academic survey platforms that thousands of academics use. Respondents on these platforms lean young, liberal, and white. But as this is precisely the group I wished to study, this is not a major limitation. Indeed, I have removed conservatives and centrists to focus only on liberals. Liberals are defined as those who rate themselves as a one “very liberal” or two “liberal” on a five-point scale from “very liberal” to “very conservative.” The liberal sample, consisting of 414 people, was 86 percent white and 53 percent male. Forty percent of liberals identified as “very liberal” and the other 60 percent as just “liberal.”

Responses ranged on a seven-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” I’ve simplified the seven categories into a binary agree-versus-disagree score. Those who scored a four—“neither agree nor disagree”—were dropped from the analysis, permitting me to gauge where the balance of committed opinion lies.

Here is what I asked people to agree or disagree with:

- Rebalance the history taught in schools until its voices and subjects reflect the demographics of the population and heritage of Native people and citizens of color

- Move, after public consultation, to a new American anthem that better reflects our diversity as a people

- Rename our cities and towns until they match the demographics of the population

- Rebalance the art shown in museums across the country until an analysis of content shows that it reflects the demography of the population and perspective of Native people and citizens of color

- Move, after an open public process, to a new name for our country that better reflects the contributions of Native Americans and our diversity as a people

- Rename our states until they better reflect the heritage of Native people and citizens of color

- Gradually replace many older public buildings with new structures that don’t perpetuate a Eurocentric order, until a more representative public space is achieved

- Respectfully remove the monument to four white male presidents at Mount Rushmore, as they presided over the conquest of Native people and repression of women and minorities

- Allow our public parks to return to their natural state, before a European sense of order was imposed upon them

- Move, after public consultation, to a new American flag that better reflects our diversity as a people

- Consider adopting a new national language, that will be forged from the immigrant and Native linguistic diversity of this country’s past

- Remove existing statues of white men from public spaces until the stock of statues matches the demographics of the population

- Gently remodel the statue of liberty to make it better reflect the diversity of America

- Rename our streets and neighbourhoods until they match the demographics of the population

- Move, after public consultation, to a new American constitution that better reflects our diversity as a people

- Begin changing the layout of our cities, towns, and highways, moving away from the grid system to follow the more natural trails originally used by Native people

Every one of these proposals represents a radical blow to American cultural nationhood. Yet figure 1 shows that six of them carry the support of more than 50 percent of committed liberals—that is, all liberals who did not answer “neither agree nor disagree” to a statement. Eight are backed by a majority of the 40 percent of liberals who identify as “very liberal.” Some 80 percent of those who have made up their mind would replace the national anthem and constitution. With the shifts in opinion we have seen in the past decade, and in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests, the views of these leftists are a good bellwether of where things are headed.

The notion that strict equality quotas rather than antiquity, mass attachment, tradition, or aesthetic excellence should drive everything from the content of museums and history books to place names and the built environment sacrifices multi-generational meaning systems on the altar of utopian universalism. Indeed, over 40 percent of “very liberal” respondents would replace the American flag and rename the United States of America!

The destruction of American distinctiveness that would be necessary to achieve this de-Europeanizing cultural revolution would include blasting Mount Rushmore, tearing down numerous grand old buildings, and letting the nation’s great public parks go to seed. Books and art might not be burned, but much would be placed in storage or thrown out, erasing and eroding a centuries-old civilization.

Figure 1.

Source: Amazon MTurk and Prolific Academic, May 7th and June 15th, 2020. N=674 (May 7th) and 196 (June 15th) before exclusions due to ideology and neutrality. Graph excludes centrists and conservatives, as well as those who neither agreed nor disagreed with the statements. N on chart reflects variation in number of respondents by question.

Generational momentum is propelling America toward cultural revolution. Averaging across the 16 questions, and controlling for education and gender, 20-year-old liberals in the sample average an “agree” response while 80-year-old liberals fall slightly toward the “disagree” side of the “neither agree nor disagree” category.

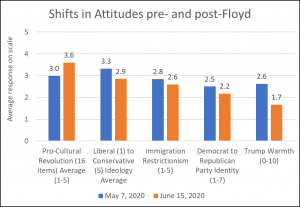

Black Lives Matter protests have stepped up the tempo, supplying oxygen to the cultural revolution. I just happened to run this survey a few weeks before the protests, so felt that it would be opportune to dip my thermometer into public opinion in the wake of them. Using the same survey platform to minimize differences and expand question range, and adding in conservatives, centrists and the undecided, produces the pattern in figure 2. Note that this time, 99 percent of respondents are white.

As it shows, support for the 16 cultural revolution questions on a five-point “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” scale rose from an average of three to 3.6, equivalent to a shift between an average response of “neither agree nor disagree” to one leaning towards “agree.” Along the way, people after Floyd’s death were a half-point more liberal on a one-to-five scale, nearly a third of a point less Republican on a seven-point scale, a full point cooler toward Trump on a 0–10 scale and were more pro-immigration. All of these protest-driven changes are statistically significant. This reflects the drop in Trump’s popularity recorded more broadly in American polls in this period. Far from being a disaster for the Left, as in the past, the protests and rioting seem to have invigorated it. America may have stepped over the precipice toward cultural revolution.

Figure 2.

Source: Prolific Academic, May 7th and June 15th, 2020. N=201 (May 7th) and 196 (June 15th). All differences significant at five percent level or less. MTurk results not included.

Culture versus equality

Today’s “woke” cultural Jacobins are acting rationally by trying to destroy the country’s traditions. Put simply, the goal of equalizing the representation of social groups clashes with the desire to maximize cultural depth. Cultural solidarity, like liberty, is in tension with the idea that groups of all kinds must have equal billing in the symbolic pantheon. Offense archaeology is the enemy of meaning-driven archaeology.

Powerful collective memories and symbols always exclude, selecting from a wide palette of historical material. Their emotional appeal is enhanced by focusing on unity, excellence, and authenticity. This is why tourists visit old monuments, not modern buildings; why they like the architectonic unity and history of Paris or Shibam in Yemen, not modern high-rise jumbles like Tokyo.

The dynamics of cultural attractiveness mean that when it comes to national identity, people privilege the patina of age, which is associated with both native or settler origins, and moral archaism. The more indigenous and morally troubling past is favoured over the tolerant and superdiverse present; core nation-building regions like Tuscany over deprived peripheries like Sicily; and elite scribes like Socrates and buildings like the Acropolis more than the slaves and peasants who sustained and built them. All offend modern sensibilities. If today’s left-modernist puritans looked behind UNESCO’s world heritage sites to see how the sausage was made, they would dynamite our precious heritage. The only reasonable aim is to strike an accommodation between culture and equality, one that preserves the past while making space for alternative interpretations.

Archetypal native traits are used to distinguish one nation from another, but the progressive who seeks to undermine this will try and personalize exclusions operating at the symbolic level. If a trucking company is underperforming, this doesn’t mean its drivers are at fault. To claim otherwise is to commit the fallacy of composition. Left-modernists routinely make this error on culture versus equality questions. Surnames like O’Reilly and the Catholic religion, for example, may represent Irish distinctiveness better than the more common Irish surname Smith, the longstanding Protestant community or immigrant minorities. This means that a zealous egalitarianism which translates claims about aggregate-level distinguishing features (“O’Reilly is a distinctively Irish name”) into individual-level claims about exclusion (“Are people without these surnames not equally Irish?”) ends up flattening identity and culture. Distinctiveness is erased, symbolic unity dissipates into bricolage, and ideology replaces culture as the fount of nationhood. Multiculturalism and progressivism become the default national identity of every country, with each struggling for the title of Supremely Progressive Nation, much as Iran and Saudi Arabia vie for the crown of being Islam’s chosen missionary on Earth.

Erasing culture and destroying the past

The past is raked over for imperfections as left-modernist ideologues render the most grievance-based interpretation of history imaginable. This wins plaudits from movement leaders on social media, much as youthful Red Guards sought to impress Mao and his commissars with their crusading zeal in destroying Confucius’s tomb or sticking up posters denouncing officials. In 1960s China, these zealots tried to outdo each other by attacking the four “olds”: Old Culture, Old Customs, Old Habits, and Old Ideas. Priceless historic monuments and manuscripts were destroyed in an orgy of vandalism designed to wipe the collective mind clean. Those who observed old customs or read historic poetry, or whose families had been merchants in the Kuomintang era, were deemed bourgeois “capitalist roaders.”

This “year zero” mentality is common among heaven-on-Earth utopian movements and corresponds to a view that people are slates that can be wiped clean and restored to their pristine, blank condition—their souls must be purified. As with the social construction of “racism” and harm, they have a point. Propaganda can alter people’s sense of reality to some degree. But not everyone can ignore the evidence that is before their eyes, which is why the Maoist or Soviet experiments ultimately failed. While social construction can shape people’s ideological beliefs, as we have seen, it is much less effective at altering scientific facts, which hit people between the eyes. Many see through the forced confessions and “struggle sessions” of a regime.

Collective memory and the monuments which sustain it often become the target of perfectionist activists because, in their blank slate view of the world, there is only one dimension to history: oppressor versus oppressed. They believe that in order to create utopia, one must burn the relics which mysteriously—though this is never experimentally proven—reproduce the current order. ISIS’s destruction of Palmyra and Assyrian monuments was driven by a similar desire to, in Olivier Roy’s words, “deculture” Islam of human accretions like shrines and poetry, to strip Islam down to pure, god-given fundamentals unsullied by the hand of man.

In Orwell’s 1984, obliterating the past becomes the first task of the socialist regime:

Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.

Substitute “racist” for “bourgeois,” or “white supremacist” for “capitalist roader,” and you find an analogous process of ironing out the particular in favour of the universal. Immanuel Kant’s crooked timber of humanity must be made straight, and the fundamentalist vision of societal perfection imposed on an imperfect past.

An Orwellian nightmare?

The elevation of a principle like anti-racism into a sacred value which cannot be questioned by science means racism becomes impossible to measure, falsify, or bound. Psychologist Nick Haslam’s “concept creep” kicks in, the meaning of “racism,” “hate,” and “harm” expand out of all recognition, and suddenly everything and everyone becomes open to being smeared. Sacred totems like the proletariat or “Black and Indigenous People of Color,” and their demonic “other”—be this “bourgeois” or “white”—have no fixed meaning. As with “racist,” their definitions are fluid and political rather than based in the reality of measurable and statistically-unlikely clusters of values of variables, which is how scientists and ordinary people demarcate terms.

George Orwell captured these puritan dynamics nicely, having witnessed factional socialist madness first-hand in Spain, and the bending of truth in Nazi Germany. In 1984, Orwell outlined the process whereby the meaning of words becomes political rather than scientific:

In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it. It was inevitable that they should make that claim sooner or later: the logic of their position demanded it. Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality, was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense… If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable—what then?

Thought control: from the state to the crowd

In Orwell’s novel, the Party controls our understanding of the past. Today, instead of the top-down English Socialist party and its Ministry of Truth we have a decentred complex system of politically correct thought control. Complex systems like flocks of birds work because all birds obey simple rules for how to position themselves in relation to other birds. All it takes is one bird to react to a predator, and the entire flock shifts. There is no lead bird with a master plan. A spontaneous order arises from uncoordinated actions and is more effective than top-down control because the crowd embodies knowledge no leader can. Markets, for instance, are complex systems which do a much better job of matching supply with demand than top-down command and control. Overseas jihadi terrorism largely operates this way, as a set of rogue actors motivated by a common doctrine and playbook, without central control.

In Mao’s time, the Party was a real top-down organization, but its resources were limited. To succeed, it relied on bottom-up mass conformity in which self-organizing student zealots, following elite cues, led the flock. Its anti-capitalist religion empowered puritanical moral innovators to make outlandish accusations against faux-dissidents which required others to conform to insane claims for fear of falling out of line with the flock. Once the norms were in place, the system reproduced itself in an endless feedback loop, with little need for central direction.

Norms are an interesting example of a complex system. No policeman is there to tell you to greet people in Western countries with a handshake instead of a bow, but it happens because it’s expected of you, and the mass of people enforce non-conformity through ridicule. This power structure isn’t hierarchical, but “flat” and leaderless. So too with norms about which forms of speech and behaviour are acceptable. These norms are a site of struggle, and change over time as norms are challenged or imposed beyond a tipping point where a critical mass adhere to them, convincing waverers and making resistance costly.

Homosexuality and atheism, for instance, are no longer the taboos they once were. The erosion of those taboos contributed to liberalism, but what happens when taboos tack in the opposite direction, toward an authoritarian censorship of critics of atheism and gay marriage, in the name of preventing “harm”? This barely perceptible change, from negative to positive liberalism, has enormous implications for human freedom. It’s in full swing because today’s dominant ideology of left-modernism has discovered that controlling social norms is the key to shifting the flock in its desired direction. The Right has been caught flat-footed, obsessed by tax cuts and foreign policy, both of which coincidentally (?) allow it to steer clear of the sacred cows of left-modernism.

Once this norm innovation is lodged in the DNA of elite institutions, government agencies, corporations and much of the media, “truths” like “systemic racism” or “speech is violence” become sacred values that cannot be questioned by evidence. Today there is still a struggle to be had, so left-modernist radicals are fighting to consolidate their grip on the ethos of institutions through advertising boycotts, Twitter mobs and internal staff activism. As under Maoism, once compromised, institutions compete to outdo each other in exemplifying left-modernism’s values.

Once the conquest is complete, the activists can step back. Mass conformity will take over to become a crowdsourced Ministry of Truth. Ordinary people call out violations, as with those who bow instead of shaking hands. People expect to be called out and expect others to call non-conformists out. The skeptic is outed from the flock as a racist, sexist, or transphobe. People soon get the message and duly fall into line, reinforcing the weight of public opinion and social conformity in a self-fulfilling loop, making it ever harder to dissent. Even without a woke Democrat in the White House, the complex system of bottom-up authoritarianism we call political correctness tightens its grip. The recent BLM protests may, in hindsight, prove the caesura.

Toward a new cultural nationalism

Is there any way to resist the woke steamroller that’s trying to iron out American distinctiveness? Yes, but this will require a concerted movement to protect the content of cultural nationhood. National identity can be understood in two registers, qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative nationalism concerns the “ascribed” particularistic distinctiveness of a nation. Quantitative nationalism pertains to the “achieved” progress of the nation according to universal values like prosperity or equality. Since the 1940s, American nationhood has foregrounded universal values, but, until recently, there had been room for the particularistic aspects of America’s culture, history, and landscape within the lived experience of nationhood. Today, it appears that the country’s distinctiveness is being hollowed out in the name of anti-racism while the shell of quantitative patriotism remains. Americans are still politically nationalist, but many aren’t culturally nationalist. Between 70 and 80 percent of millennials are patriotic, but are increasingly open to replacing the content of Americanism, a heritage that’s endured for centuries. The younger generation is leading the charge, but have learned a lot from their parents, who are already well down the road.

The concept of cultural nationalism refers principally to 19th century minority nationalists like the Welsh, Estonians, or Irish, who sought to unearth ancient chronicles and rework them into national histories, catalogue folk traditions and create written high languages out of spoken dialects. Often language loss and the threat to collective memory was the spur to action, as with the Irish and Welsh. Cultural nationalists are less concerned with political goals except insofar as these are needed to protect cultural distinctiveness. The key to such movements is a viable set of institutions that can protect and reproduce culture and identity. Sometimes they succeed, as with Israel’s revival of Hebrew or Quebec’s defence of French, and at other times they fail, as with the attempt to save the Provençal dialect from being replaced by standard French in the 1850s, or the dream of a Gaelic-speaking Ireland.

Often, minority groups within empires used religious institutions and literary societies to revive their cultures and resist homogenization. Czech linguistic revivalists, for instance, published dictionaries of Czech to try and ward off Habsburg attempts to Germanize them. In Ireland, the Catholic church formed a site where the Irish communal narrative could resist Britannic assimilation. Cultural revival movements have also occurred among the great powers, in the form of the Gothic revival in France, Britain and elsewhere during the Romantic period in the 19th century. Here the aim was to revive symbols and historical episodes that had been downgraded by the Enlightenment.

Today, some groups are trying to protect their traditions from today’s softer, progressive deconstruction. An interesting present-day example are the Ulster Protestants of Northern Ireland, most of whom, despite a small Free Presbyterian fundamentalist minority, are fairly secular and socially liberal. A formerly-dominant group with a history of discriminating against Catholics, the Ulster Protestants are deeply unfashionable. But they are not about to disappear out of a sense of shame. Their collective memory and culture is reproduced almost entirely outside the formal institutions of the British state. Though widely viewed by the British elite as a group on the wrong side of history, the Ulster Protestants have managed to protect their identity in the face of state neglect and scorn from the mainland British media. Civil society institutions like the Orange Order, along with local branches of the Unionist parties, safeguard culture and collective memory. They have education, culture, and historical committees that produce local and communal histories, maintain memorials and organize re-enactments of key events in Ulster-Protestant history. Though arguably too conservative, their institutions ensure that the culture and memory which underpins community is protected.

In America, patriotic societies like the American Legion or Daughters of the American Revolution, fraternities like the Masons and ethnic associations like the Sons of Italy once performed this role. With today’s partisan divide, and left-modernist control of education, the quest for a unified memory, taught in schools, is a chimera. The best the centre-Right can aim for is to resist the demonization of established traditions, and rebalance the teaching of history to de-centre the narrative of oppression, according it a weight proportionate to its role in a balanced pedagogy: one of several vantage points on the national story.

Faced with neglect or hostility from the media and educational establishment, conservatives should use civil society institutions, associations, and media to keep the country’s customs and traditions alive in recognizable form. This may extend to advocating for, or relocating, statues and other elements of heritage. In 2006, John Judis and Michael Lind called for a Rooseveltian “new nationalism” blending economic equality with cultural unity. This needs to be augmented. A new cultural nationalism offers the best hope for the survival of American myth, symbol, and memory. Whether the American consciousness survives or goes the way of the Provençals depends on it.