Long Read

When I Was in Love with a Comparative Literature Student

The first time we hung out, we read together in an empty classroom.

She said she did not believe there was such a thing as love—not because she was embarrassed by sentimentality, but because Jacques Derrida had convinced her that language did not actually refer to an external reality.

I met her during the period she was reading Derrida’s Of Grammatology. Or maybe it was when she was reading Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, which for weeks she kept open and in front of her at the campus coffee shop. At least once, she carried Heidegger into a bubble bath.

The first time we hung out, we read together in an empty classroom. I was reading Philip Roth’s novel American Pastoral for a literature class. She was reading “The Concept of Irony” by literary theorist Paul de Man for fun. As in every classroom, there was a clock at the front of the room. The sound of the ticking, which I had unthinkingly accepted as an imperfect part of our environment, irritated her. She stood up on the table and flung the clock to the ground.

She put her hand on my shoulder, and asked if I might like to read some of her de Man. He wrote strange highly theoretical essays: “The Epistemology of Metaphor”; “The Rhetoric of Temporality”; “Form and Intent in the American New Criticism.” I had become an English major to learn deep truths about human nature, existence, and to write a great novel. I had not even been aware that one could approach literature theoretically. All I knew was that de Man was part of something called “Deconstruction.”

When I arrived at Reed College, I had a lengthy list of burning questions—the result of a youth poring over the Internet trying to comprehend a seemingly infinite number of concepts, people, and eras. At 17, I would spend an hour trying to focus on the Wikipedia page of “Modernism” only to be chagrined when I learned that there is in fact also an entry on “Postmodernism.” Even that there are certain writers I had never read (Gibbons, Burroughs, Borges) who are essentially linked to this movement that I did not understand. And within this movement (Or is it a period? Or an era? Or, as one critic I read once asked, is there even really such a thing as postmodernism?) there are a number of different critical movements including “Structuralism” and “Post-Structuralism” (which I was pretty sure was not to be confused with “Postmodernism”) and of course “Deconstruction.”

Whether because of Deconstruction itself or de Man’s style, I did not understand a single sentence in the essay. When I’d had enough of nodding and smiling at the page, I passed the book back to her. I returned to my novel, and almost instantly gave a big laugh to show what a bright thinker and lover of the higher things I am. Five or 10 seconds later, as she continued to read de Man, she began to laugh at least five times as loudly and as passionately as I did. She had won.

Her name was Camille. Originally from Spain, she had attended a baccalaureate high school in China, and had elected to go to college in the United States because, as she said, she wanted to see another continent. When she first arrived in America, her plane got in before the dorms opened; she spent the entire night alone in the airport “reading Virginia Woolf and hating America,” she told me in one of our first conversations. She had recently, and by her own account, unexpectedly, returned to Reed after temporarily dropping out and hitchhiking for months across Europe.

Even after years of knowing Camille, I’m not sure I ever got the full story of that time in her life. But that’s just how Camille was—dropping a tiny anecdote here and there as if you already knew the backstory: “You know, when I was hitching…” she’d begin a sentence, perhaps the first time you ever met her. In one conversation, she might be describing how many cheap cigarettes she smoked in Morocco while working on her novel; in another conversation, she might be referencing one of the “mad ones” she met on a spontaneous sojourn to Amsterdam.

But even when she told me these stories for the first time, I could already tell she believed they were from a part of her life now gone. She spoke of such rich experience, and yet somehow seemed to believe her life was already over.

As I soon learned, Camille never described anything without attempting to theorize its place in a broader system of ideas. She was a year older than me and, though she had always retained her self-identification as a Marxist, had already gone through various periods under the influence of the Surrealists, Herbert Marcuse, and the Situationists—periods in which all of life, from the highest abstract considerations, to a random excursion in Europe, were interpreted through a singular theoretical lens.

When I met her, this frame was Deconstruction. But Deconstruction somehow wedded to Marxism. As I began to pick up here and there from Camille, Deconstructionists believed that attempts to express meaning through writing were somehow undermined by writing itself. This had helped Camille clarify her central conviction: “Experience” is not possible.

“It’s like when I hitchhiked to Rome,” she said, again, as if we had known each other for years and I was already in on the subtext of her life, “I was reading Shelley, and the whole time I thought to myself: I’m doing it!” Like me (at least in my fantasies) she had set out to find meaning in the way she imagined other writers and intellectuals also found meaning: spontaneity, outrageous acts, beauty, and so forth. But when she actually arrived (in Rome, Morocco, or a nearly deserted island that an Italian man introduced her to somewhere in the Mediterranean Sea) there was no unselfconscious sublimity. Instead of something that gave her meaning in her life, she felt only the great gap between her hopes for experience and her self-consciousness of its emptiness. When she read Shelley in Rome she was not suddenly transported to a new world of significance. Rather, she was just aware of her desperate attempt to find meaning.

She seemed so much bigger than me, both in life and in thought. Whereas I was just beginning to learn who I should read, she seemed to have already tied together broad ideas into a coherent system. I was certain that once I understood her language, I would find at bottom some definite, albeit strange truth. I needed to understand her ideas even if it meant becoming a new person. I sensed I was on the cusp of a new part of my life, and that Camille uniquely possessed some insight into who I would become.

In short, I was in love with her. And while “love” assumed there was an objective real outside of language, she did have a polyamorous “relation” (her description of choice) with an older boy, John. He was known around campus as the Marxist who had decided at 17 he would fall on his sword for the cause. According to one rumor he had grown up on an anarchist commune and was teaching Immanuel Kant to children by the time he was 15. Another rumor said that during a literature class he had gotten into daily arguments with the chair of the English department because she insisted (a heresy that went over my head) that the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan was a Humanist. At Reed, he had founded a discussion group on Hegel where students spent their Sunday mornings listening to him monologue about various passages in the Phenomenology of Spirit.

Meeting John, Camille said, was the one period in her life in which she really felt she had experienced something—when she really did find some deeper sense of meaning in her life. She first saw John in a course on the Frankfurt School intellectuals. Though Camille had considered thinkers like Max Horkheimer and Walter Benjamin her area of expertise, every day in class John would make a single comment that would “destroy everything I had planned to say.” Camille began reading and writing every night in the library until past midnight. Instead of going home, she would then work in whatever available room she could find until she physically collapsed.

When she found out where John sat in the library, she prepared to leave a note on his desk. She waited until the 16th of the month, and wrote “Cigarette at 19:04?—Camille” as a reference to Bloomsday in James Joyce’s Ulysses. She made a misstep and ran into him in the library’s printing room before her appointed time. She was so nervous that she began to shake. Without a word, she ran away. “Even if I never experience that again,” she told me, “I am grateful I had it once in my life.”

When I first heard John speak—about how he wanted to continue the Frankfurt School tradition of linking psychoanalysis and Marxism—it was more incomprehensible to me than Paul de Man. I was so intimidated that I couldn’t sleep that night. I attempted to console myself by recognizing that I had changed a great deal between the ages of 16 and 19, and there was no reason to think that I couldn’t change even more from the age of 19 to 22. Toni Morrison wasn’t published until she was nearly 40. Kant didn’t write the Critique of Pure Reason until he was in his 50s. Just because I didn’t have the charisma of such a thinker yet, I could still develop it.

In addition to John, who graduated my junior year and went back to Chicago to help run his organization, the Institute for Psychoanalytic Inquiry, there were other Young Hegelians (as they called themselves)—Juan, a French literature student whose youthful Marxist activism had dissolved into a life of drugs, cigarettes, and books; Jessica, Juan’s primary lover, a one-time union organizer who studied literature; and Fatma, a German literature student from Turkey who analyzed her love life in terms of Hegel (you see, the master slave dialectic…). These were the friends I had always wanted: politically and artistically radical, absorbed in Marx as much as they were obsessed with the avant-garde, as likely to be found on a Saturday morning in the library smoking with their legs up as they pored over commentary on Das Capital (red underlining everywhere, in the zone as a result of caffeine or drugs or both) as they were to be found listening to Wagner’s “The Ring,” anti-American and cosmopolitan.

One evening Camille and I sat on a bench smoking and she asked me, curious about my course of study, “Why English?” I felt that this was my conditional invitation to the Young Hegelians. My answer to a question like this determined whether or not I was worthy of their company. And even if there wasn’t so much depending on my answer, for as long as I could remember I had wanted someone to take precisely this interest in me; to sincerely want to know why I was pursuing an education, and not assume it was some lame and uninspired decision based upon one banal and inauthentic factor or another.

I tried to describe an experience (generally, I avoided this word in front of her but sometimes it was required) I’d had a few years earlier. “It was a profound philosophical illumination,” I said, pretentiously and sincerely. She laughed. I couldn’t tell if she was trying to make me feel comfortable, or if she was just amused, but either way she wanted me to continue. I explained that when I first read Jean-Paul Sartre’s lecture Existentialism is a Humanism I was influenced by his idea that an individual can break free of social influence in order to become a self-determined authentic person. This philosophy had inspired me to come to college in order to discover my purpose as a writer and an individual. But just by reading him, I had an insight into my essence as an artist.

“None of us have an essence,” she said, dismissively but casually. “Who you ‘are’ is always different depending on who you’re talking to.” As Deconstruction had helped her clarify: There is no essential nature or objective truth. The world is just our perception of it, and perception is always relative to a particular perceiver. There is only the person I am in a particular context in relation to another particular person. I felt my hope of self-discovery shatter: The Self, I realized, is an illusion. I thought this rebuke was bad enough, but over the following weeks I learned that in my attempt at a lofty speech I had tripped over a number of intellectual taboos.

“Jean-Paul Sartre is barely a philosopher,” Camille said, as she relayed various embarrassing influences upon her younger self (for example, Alain Badiou’s In Praise of Love which had ignited her passion for worldly experience shortly before she began reading Derrida and de Man. “Don’t read that,” she once told me, “That’s what convinced me to almost drop and hitchhike across Europe.”). It was as if she did not remember that I had ever discussed Sartre. She may have also just not cared about offending me. When she began her tirade against him, I did not reiterate that I came to college under the influence of Existentialism to learn who I was. She however noted repeatedly that she “came to college in order to learn how to be a good Marxist.”

When I was a teenager I thought being a Marxist meant being generally on the side of the poor, and hating the emptiness of the bourgeoisie. Easy enough. But Camille had been raised on Marxism since she was a baby. As I learned, Marxism has great philosophical implications that contradicted many of my beliefs. Camille explained to me: The individual is a construct. The idea that a self freely determines his or her beliefs is an illusion of capitalist ideology. The individual’s view of the world is conditioned upon his or her position in the material system of production. There was no such thing as authenticity.

Clearly, I had to re-educate myself. Camille and her friends were so certain of themselves that I believed they must be onto something. Even if they didn’t think like I did, and even if I barely understood half of what they said, they seemed so much to be the intellectuals of my imagination. And either way, no talk of the individual and meaning was going to impress Camille.

One Saturday at 7.30 in the morning I sat in the quad with a pile of books by theorists like Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and Hannah Arendt. As I lit my first cigarette of the morning (I had begun to smoke about a pack a day) my roommate walked by. “That’s quite a lot of books…” he said. “It’s for a girl,” I said, ironically, and un-ironically.

I wanted to do more than just establish a passing familiarity with this canon. I wanted to absorb everything she read so that I could impress, exceed, and even overpower her with my ideas. If she wanted John, then I would become a more profound version of John. One might say that this was not love, but a destructively competitive intellectual obsession. But in Camille, eroticism and ideation were so bound up with one another I could not tell them apart. I recalled how in Plato’s Symposium, the lover of a particular person is distinguished from the philosopher, the lover of abstract wisdom. But I believed that if I really attained the truth, I would become the person she wanted, and thereby become her lover. To say I wanted one or the other would have been reductive.

One evening we stayed up all night together reading in Reed’s performing arts building—a translucent structure through which the evening darkness poured in. I read literary theorist Stanley Fish’s book Is There a Text in this Class? in which he argues that there are no objective standards of literary interpretation or what constitutes a text, but rather that such standards are decided upon by different communities of scholars. I had the general sense that this theoretical approach and these concepts—relativism, anti-foundationalism—had something to do with Deconstruction.

Camille had two books: She was using Freud’s Interpretations of Dreams to help her interpret a strange Jacques Derrida book, The Post-Card. The cover of this book was provocative. In the garbs I imagined a medieval scholar wore, Socrates sat at a desk as Plato directed his writing. Even if I hadn’t read Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition, I knew this image was a perfect symbol for the collapse of contradictions and differences that characterized so much “Postmodern” thought.

When she saw that I was reading Fish, she told me she found his work childish. I told her that I had barely read 10 pages and was just interested in learning about his ideas. “Don’t bother,” she scolded, “He’s not saying anything.” She had no interest in discussing someone she had already dismissed. Eager to show her I could stand my ground, I gathered scraps of what I’d already picked up from reading Fish and from thinkers I knew that Camille preferred. Using words I knew Camille had used to describe other theorists, I contended, with faux-authority, that Fish provided a way to understand the “politics” of academia, and could help us understand “power” in the university… or something like that.

“Yeah,” she said, suddenly intimidated. I wondered how many times she had spoken, half-conscious of what she was saying, just to see my embarrassment and fear. Frequently I was afraid to challenge her simply because of her tone and the references she made.

We sat alone in the building, looking out through the open glass at the night, here and there going out for cigarettes, reading as we discussed our futures. Like me, all Camille wanted to do was write. But while she admired independent writers like Marx who wrote every day in the British library and died poor and all but alone, she wasn’t sure she could actually bear this. I asked what she wanted to write about. The subject would be something vaguely in the universe of Deconstruction and Marxism. What was far clearer was that it had to be a book that transformed academic discourse, that was included in a significant number of college courses, and this all had to be accomplished before she turned 35.

“If I’m still unknown then,” she said, “I think I’ll just give up. That’s when I’ll start just having fun with experiments—like seeing how long I can go without talking to anyone, or covering my eyes with a blindfold for days.” She contemplated this with glee, even anticipation at finally being free of the pressure she put on herself. I couldn’t understand this apparent paradox. Despite her intensity of focus and interest, and she had the most of anyone I’d ever known, she seemed so willing to give it up.

There were so many moments in which I thought to myself, I’m having this kind of conversation. Even if I wasn’t saying anything special, anything more than I’d thought in my head a thousand times, I felt my desire to be amidst the intellectuals somehow satisfied. I wondered if she was thinking the same thing. But she seemed so naturally engaged in her thoughts, or at least so accustomed to her life as an intellectual. Even though she had told me she did not believe in experience, it seemed to me that she was the one really experiencing the conversation; I was just there and aware of it.

Around four in the morning, not nearly as compelled by Fish as she was by Freud and Derrida, I decided I was ready for bed. I got up to leave, but before I walked out, I turned back towards her.

“May I kiss you?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she said calmly. I bent down to her, and sat in the chair next to her as we kissed for a minute or two. She looked at me as she touched my hair.

“You’re a funny person,” she smiled.

“What?” I asked, begging to understand what she meant.

“Nothing,” she half-smiled, “Have a good night.” She touched my arm and went back to her book.

I thought far less about the kiss than what I believed it signified. That is, a new epoch in my life. It was like the first kiss between Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. I never considered whether I enjoyed the kiss, or whether I wished we had kissed longer. That would have seemed utterly trivial. Rather, what seemed important was the great poetry and philosophy that would emerge from the moment.

A week went by and she still had neither mentioned the kiss, nor indicated she was interested in another. Granted, I thought, I haven’t mentioned it. Perhaps she’s just nervous. After all, she could barely speak to John at first. Finally, a couple weeks later I asked her, “What do you think about what happened?” She shrugged. “Honestly,” she said, “I haven’t thought about it much since.” I did not mention the fantasies I was engaged in—the lines in her biography (or mine) devoted to documenting how her thought dramatically changed after our relationship began.

She explained that her polyamory was based upon the detachment of sexuality and commitment. It was a more ethical philosophy than monogamy because it didn’t conceive of people as possessions and it did not moralize about sexuality. She happened to be sexual with John, but that could easily change if she felt more attracted to someone else. There was no point in discussing what happened because there was nothing to talk about: If we happened to want to (I was thinking, if she happens to want to) then we’ll kiss more and see how it all goes.

After that conversation, it was not uncommon for us to kiss (or more), but each time there was the same nonchalance (at least on her part), lack of pre-thought, and discussion afterward. As she read Dialectic of Enlightenment next to me in the library she might open her legs as I put my hand on her thigh. As we walked through Portland together we might begin to hold hands. When I was in her apartment we might, here and there, begin to kiss. It was obvious to me that she did not take this relationship very seriously. Even though I was angry, I felt that her theory was correct, and I had no reason to object. I had no right to demand anything from her. I had to recognize that my jealousy was based upon an improper view of relationships and ought to change.

Meanwhile, her relationship with John continued equally as intensely. It was not uncommon for her to sit down next to me overjoyed. “Sorry, I know this is like a teenager thing,” she said at one such encounter, visibly red in the face as she sat down next to me and opened her computer, “John emailed me.” She proceeded to read me an email in which he wrote that he was thinking of her. She insisted she only read such letters because they were “good writing.”

Again, I felt merely aware of our relationship. Camille was the subject of experience. Her dynamic with John seemed of such significance: two theorists committed to and absorbed in so many great writers as they developed an intense affair. I was the relief that kept her from boredom. He was so essential to her life that he came up frequently in our conversations. If I was ever mentioned at all, I am sure I was a punchline: the foolish romantic who read Sartre. Theirs was the relationship worthy of a story. I was, if anything, a jester; far inferior to a villain, for I had no power to change the course of events.

But I still retained hope that if I really developed myself as a thinker, we could be closer. I read every night for hours, particularly for the classes that we shared. Every time I thought I was getting closer to impressing her, I realized I was mistaken. When we read Borges’ “The Library of Babel” together for a class, I attempted to impress her by saying I thought there was a strange complexity to the psychology of the characters. She was appalled. I had committed the realistic fallacy: treating a text as if it represented a real person capable of psychology. She mockingly referenced her uncle who said, with all the arrogance of common sense, that literature imparts truths about the human condition that stick with you. According to Camille, this was bland humanism. In order to properly study literature, Camille believed, we had to examine texts in terms of their formal properties: their rhetoric, their grammar, the way they attempt to create meaning, and so forth. As Paul de Man says in Resistance to Theory, approaching literature theoretically is about moving beyond the historical, aesthetic, and psychological dimension of literature—all that literature references outside of itself. We’ve known that since Structuralism, Camille would say, Deconstruction just theorized the fundamental instability of signs.

I still did not really understand Deconstruction. But I understood what I needed to understand in order to get on Camille’s good side. In my course on Shakespeare I sent the professor a long email explaining that it was intellectually bankrupt to operate his course under the assumptions of humanism: If students want to analyze psychology then they should go study psychology. Didn’t they understand that language didn’t really represent something outside of itself? That what is signified by a sign, is really always another sign? The professor was sympathetic and told me to speak more in class to make my views known. Shortly thereafter I openly derided a girl for spending time dwelling on how she liked the character Coriolanus. At the end of the course, I reviewed the professor by saying that, while he had studied with great literary theorists at Cornell, he had obviously failed to learn anything.

There were however limits to my attempts to try and impress Camille. One was my discomfort with breaking rules. Or, at least my discomfort relative to Camille’s ease. Unlike me, she enjoyed stealing. It was not uncommon for her to say, as we sat in a campus lounge, “How do you think that chair would look in my apartment?” She stole from the dining hall on almost a daily basis. Sometimes I would hide a juice or a cookie in my pocket to show her I was cool, but that was nothing compared with how she would casually walk out the doors with a stolen sandwich that she had just asked one of the kitchen staff to prepare.

The world would be much better if everyone stole, Camille explained to me one day in the dining hall, eating food she had just stolen. I believed there were some obvious holes in her argument. I wanted to counter her with some boiler-plate defense like: Wouldn’t that just destroy the incentive to produce? Wouldn’t the entire economy immediately shatter if there was no longer any profit? Instead I remained quiet. I feared she would reference some theory that I didn’t know about, or that she would see me as a capitalist ideologue.

We were, to be sure, all relativists. But this relativism in no way conflicted with our Marxism. Despite believing that there are no moral truths, we still felt certain that the political and economic system was fundamentally immoral. If you asked us for an explanation of how we could be both relativists and morally outraged by our current political and economic order, I’m not sure we could have given you a clear answer. It was as obvious to us that moral absolutism was the moral attitude of a rube, as it was that the nation-state and capitalism had to fall.

Another challenge was Camille’s paradoxical openness to pursuing experience. Even as she would deride meaning, she never really changed her actions or her hopes for experience. Some days she would disappear inexplicably. I’d find out later she had taken a day-trip alone. She would spend hours in museums and then relay her aesthetic visions in such detail that she made you jealous of her capacity for experience.

One Friday afternoon while we walked together, someone on campus offered her some LSD. With pre-meditation consisting solely of a devious smirk, she put the tab on her tongue. She said she wanted to have an interesting evening alone. The next day when I eagerly asked her how it went, she looked off into the distance and laughed as she described how wonderful she felt while high. In the preface to Michel Foucault’s famous The Order of Things, Foucault describes how he laughed upon reading Borges, and this laughter expressed a great recognition about the foundationless nature in which human beings categorize the world. This kind of laughter—prophetic, joyously full of philosophical implications—was Camille’s whenever she described such a moment. Yet, she wasn’t happy.

“If we’re going to have that exaltation so briefly, whenever we do things like this,” she said, referencing not merely drugs, but all that one does in an attempt to live, “Then what’s the point?” Her supposed wisdom about the impossibility of meaning got her nowhere. Just like everyone else, she went through periods of inspiration and enervation, even if these periods were far more intense in her. Her cynicism perhaps made her more aware, but not any less desperate for experience.

There was no point in bringing up such contradictions for Camille had no problem with contradictions. The “Self” being in reality nothing more than a collection of different perceptions and actions, dependent upon the moment and perceiver, was a fiction. She told me once that if she could start all over again, she would begin by lying, for then she would not even feel the obligation to pretend to live a coherent life, to display authenticity amidst all her inner contradictions. She looked at me and smiled.

“Did you like that story I told you about the airport?” I didn’t know what she meant at first.

“You mean when you arrived here and you were reading Virginia Woolf?”

“Yeah, did you think it showed something…?” she asked.

“What do you mean?” I wondered.

“You know… that I’m independent or something like that,” she laughed. She was not in search of any resolution, self, or truth. Her contradictions were just that.

And this willingness to play with me was just one more example of how differently we treated each other. At some point I realized I was only existing in relation to her. I had no books to recommend to her: she knew them, thought they were too humanistic, or too philosophically simple-minded (“you’re seriously reading Rorty?”). I was so absorbed in her language, I could only conceive this thought through half-baked Hegel: I wasn’t being-for-itself, but being-for-another. I had wanted to move through her in order to understand her. Really, I was just becoming more like her.

One night we were smoking a cigarette together outside the library. Camille told me that she had been thinking a lot about Oscar Wilde recently. Wilde believed art actually changed one’s perception of the world. How we perceive clouds actually changed when they were painted by the Impressionists. Mhmm, I mumbled, trying to think of something interesting to say.

“You know I’m very much like Oscar Wilde,” she said.

“I see,” I said.

“And you’re like Oscar Wilde’s assistant,” she said, “You’re not really part of the scene with me. You’re more like a bourgeoisie who’s studying medicine. I kind of like you, but really I’m only interested in you because you have some hot brother who I want to get to know.”

I put my hand on my chin and tried to act like I was responding to this in a cerebral manner. Instead of allowing myself to feel and display my mortification, I was trying to convince myself that I was coming up with some reasonable interpretation of what she had just said; that there was some theoretical idea behind her comment.

“See,” she continued, “You’re looking at me trying to figure out what I just said, like there’s something really important there. That’s exactly what Oscar Wilde’s assistant would do.”

One day finally, I decided to tell Camille how I felt. In a lengthy email, I told her she was only interested in me as someone she could use to talk to about her ideas. She didn’t actually care for me. I wanted to be seen for who I am. But I didn’t say it like that. I told her that her “house of incest” (a reference to Anaïs Nin I thought evocative) which she mistook for intimacy was suffocating. I tried to bring down her opinion of herself by mashing up Plato’s Apology and Yeats’ “No Second Troy” to write: No second cup of hemlock will be poured for you.

A few days later we sat down in the basement of the library to discuss the situation. I had only been able to get her attention by agreeing to meet during a break from her reading. “Do you really think there is an objective world out there?” she asked. She was annoyed because I had attacked her for how I perceived her to be, not how she really was. There was no real Camille; just my perception. She was willing to talk to me, but she didn’t think that there was much of a point.

I needed to get her to listen to me. In a moment of inspiration, I remembered Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach—hitherto philosophers have only succeeded in interpreting the world; the point is to change it.

“I wasn’t trying to use language to represent,” I explained, “I was trying to be performative to get your attention. I was trying to change how you see me.”

“I see,” she said, much more interested in my letter now that she could interpret it compatibly with Marxism, relativism, and a performative theory of language. “That makes sense but… Honestly I don’t think much is going to change.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. She thought about this for a moment.

“I think that for you, this is all a tragedy. There are great stakes, you’re attempting to make a big change, there is failure. For me, this is all a comedy. Not much changes, there’s a happy ending, and nothing is that significant. And I don’t get why you’re stuck in the tragedy. You can join us, you know? It’s fun here in the comedy. Why don’t you?”

“I don’t know,” I shrugged, feeling that nothing I wanted to say was justified.

When I said goodbye to Camille she was leaving for Europe, and I was returning to my home in New York. We had vague plans to meet up in Berlin. Before we parted she told me she had a gift for me. She handed me Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. We hugged, and she kissed the space between my cheek and my neck.

As soon as we parted I flipped through the pages of the book, hoping there was an inscription somewhere. This is where, I knew, she would finally tell me her feelings. As I moved through the book, on a random page I saw “love.” I began breathing quickly, for now I knew the truth. I found a quiet place on campus to sit down as I lit a cigarette and got ready to read. For whatever reason, perhaps simple embarrassment, she had been unable to tell me this in person. But in reality, she loved me. We would meet up in Berlin and we would finally be able to be together.

As I slowly flipped through the pages, looking for the one upon which I had read “love,” I realized that many of the pages were covered in notes and underlined passages. Pages here and there were ripped. It was clear that this had been her book for a while now. Finally, I saw a long inscription towards the end of the book. Along the top of the page were various doodles and random words.

“I love you John,” it read in the middle, “When I traced my tongue across your chest and told you these words, you said them back to me, but they were not really yours. But I love you, I love you.”

I continued to flip through the book for a few minutes. Perhaps she wrote that note during a day-dream a year ago and had forgotten about it. Maybe there was another inscription that she had written for me on this occasion. I pulled on my cigarette as I realized, with a feeling of inevitability, that there was nothing here for me. I sat quietly holding the book. I wondered whether I ought to keep it as a reminder, or immediately throw it into the garbage. I took out my lighter, and ripped out the page with the inscription to John. I lit the bottom of the page, and watched each of Camille’s words become black and illegible. The page disintegrated and slowly flew away. I lit another page, and then another. I burned each page until there was nothing left except scraps and then, feeling that there was nothing more I could do, I walked away.

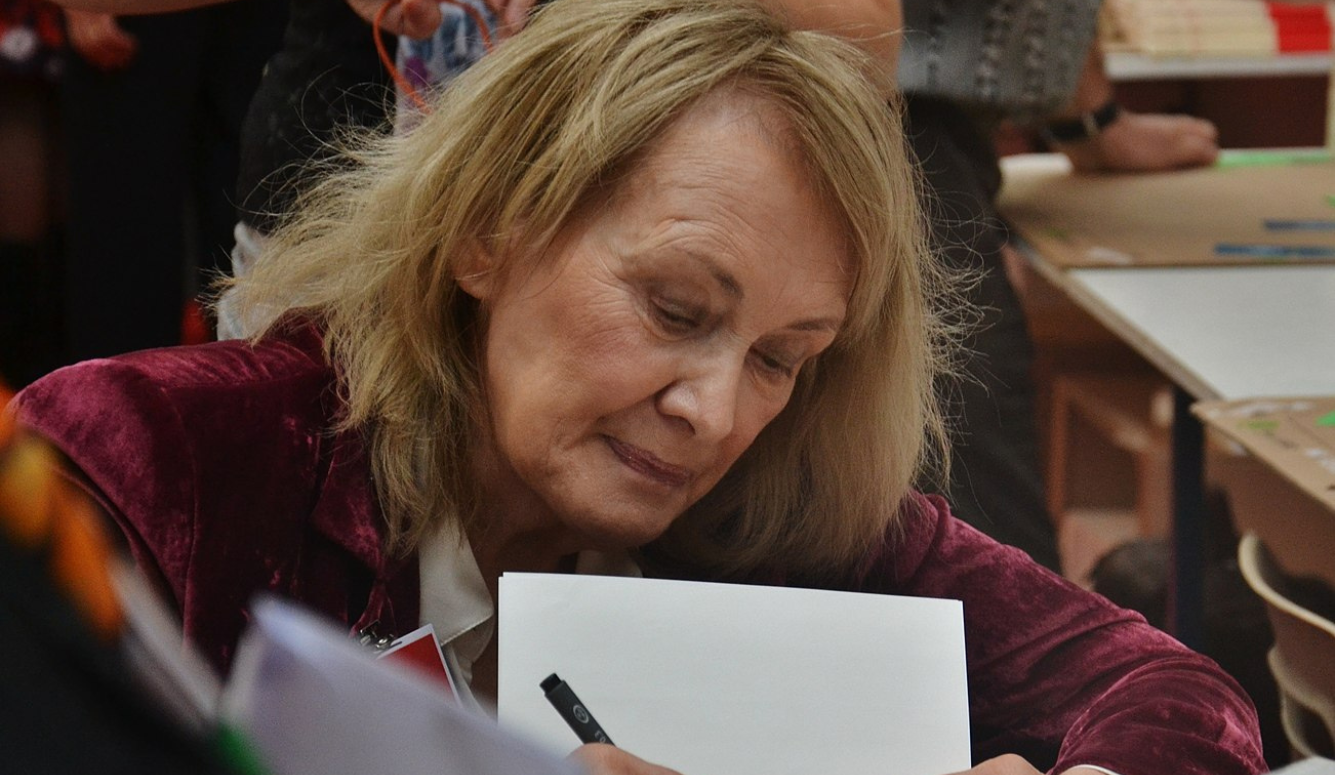

This is a personal essay based on the author’s experience at Reed College. All names (except the author’s) have been changed to protect the privacy of those involved. Photo by Ali Yahya on Unsplash.