I was going to start this essay by writing that, even at the best of times, long-distance relationships are difficult. But that’s not true at all. At the best of times, a long-distance relationship is wonderful, even ideal. After all, my boyfriend and I are both grown-ups. We have our own incomes, our own homes, and our own children. We have our lives figured out, and I am quite content to manage my affairs on my own, and to have my own space to breathe in. Spending time with him is always something to look forward to, and it is always exciting. He travels a fair amount for work, and that is usually when we see each other. What could be better for a hard-working single parent than romantic getaways to exciting cities, luxury hotels, and fine restaurants? Harried mom by day, Bond girl by night. That is how our relationship makes me feel. I’m happy with the distance, most of the time—even longing for someone who is far away has its own romance. Yet often I am asked by my coupled friends, “Sure, this all sounds very glamorous, but where is this relationship going?” To which I have replied, “I am going to Paris next Saturday. Where will you be going with your husband? Home Depot?” God, I can be smug.

Still, it’s true: at the best of times, a long-distance relationship may be the most perfect combination of intimacy and independence. But these are not the best of times, not by a country mile—and there are many country miles that now separate me from my lover. Miles, and a closed border; I live in Canada, and he in California. The pandemic has abruptly ended the luxuries of our relationship. Worse, it is because of our decadent travel-rich culture that the pandemic has arrived here in the first place. Because of this, I suspect that non-essential travel will not be encouraged or even accessible for at least a few years to come. All the romance of our relationship has abruptly been replaced with an as yet undetermined but certainly long period of doing nothing but waiting. And waiting. And of course I think of my coupled friends who have at the very least another adult to talk to, and at best a friend and lover with whom to spend lazy mornings in bed. I’m not so smug anymore. Now I have to wonder if my long-distance relationship can outlast the lockdown. Now I have to ask, “What is a relationship for anyway?”

Traditionally, a romantic relationship formed the basis of the family unit, which in turn was the bedrock of civilization. My students and friends are commonly shocked to discover that relationships have been the same, more or less, for centuries. In Shakespeare’s England, for instance, around 400 years ago, the average age for a man to be married was around 27, and for a woman, 24. My friends are also surprised to learn that most marriages were not arranged couplings, but were mutually agreed unions by the young woman and man because the two simply liked each other and fell in love. Arranged marriages were of course the norm for the upper classes who had property and wealth to consider, and very often it was mothers, aunts, and grandmothers who engaged in the diplomacy required to arrange such marriages—fathers are, let’s face it, often pretty weak at social networking.

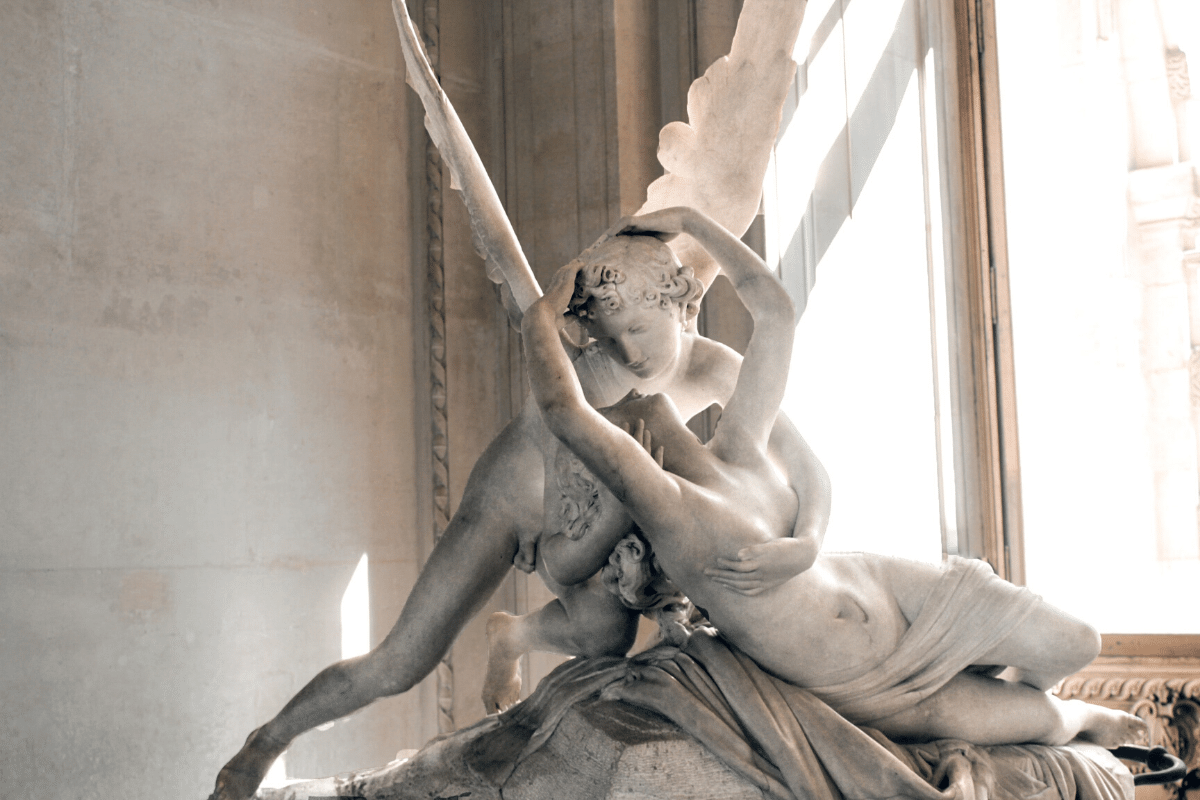

But most people were not upper class, and for the poorer classes even unofficial common-law couplings were, well, common (that’s why it is called common-law). Romantic relationships were for sexual fulfillment and friendly companionship, and also for economic and social stability. Marriages based on mutual attraction would, ideally, continue to foster romance, even under the humdrum realities of domestic life. The pull of sexual desire, far from being an instinct that social controls were to curb, was in fact the opposite: It was the very foundation of a society in which the private lives of couples formed the structure of the economic and social whole. We are seeing a return to this right now: With our modern institutions of state-run schools and daycares closed, it is once again the home economy and the family unit that is keeping society together. What a relationship is for has, in this way, come into focus for us in ways that have been opaque in modern times.

But where does that leave those of us who are dating, single, or (like me) dating-ish? When I ask Google, that repository of contemporary wisdom, “What is a relationship for?” the answer is that being in a relationship is “healthy.” I’ll live longer, apparently, if I’m coupled, and I’ll be more financially stable. Also, a not unimportant point, someone will be able to help me with domestic work. I will feel validated as a person, which will also enhance my overall sense of wellbeing. In short, the reasons I should be in a relationship seem to all be because doing so will be good for me. Vulgar self-interest is, in the end, the reason we should seek love? It looks like the poets were wrong about love being a mystery, one that could inspire us to move past self-regard to a higher state of selflessness and joy. Instead, we are encouraged to focus more intensely on how others might be of use to enhance self-love. This sounds less like love and more like emotional miserliness.

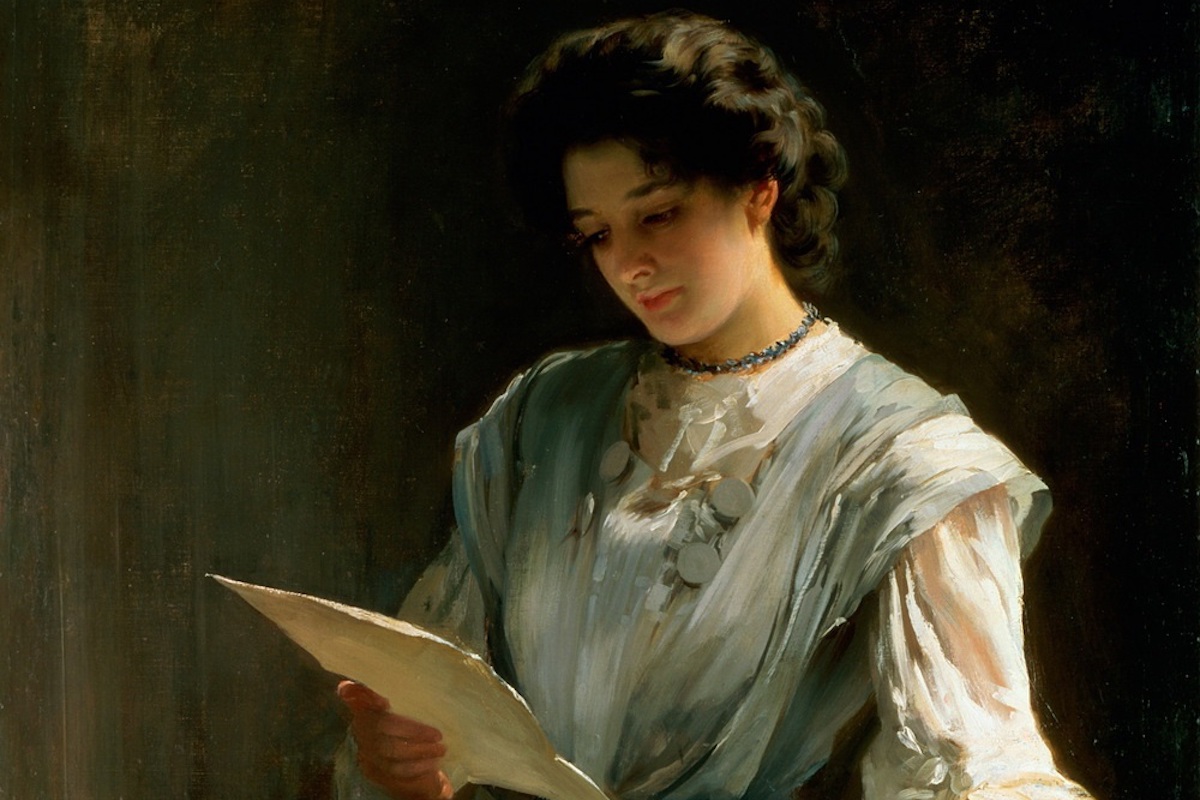

According to pop psychology, there is no tangible reason why I should stay in a long-distance, cross-border relationship that can provide no companionship during these lonely days. (I’m so desperate for touch that I find I’m brushing my own lips tenderly across the delicate skin on the inside of my wrist. But it’s not the same as a real lover’s touch.) My lover can provide no financial support, and certainly he is no help with the tedious task of homeschooling children, nor with the endless parade of dirty dishes. There is no upside to this relationship anymore. I find, even, that I’m more psychologically and emotionally agitated during this pandemic because there isn’t an end date in sight. When will I be able to see him again? When will the airplanes, all parked in some hanger in Arizona, start flying? We can’t even drive to each other, unless we want to just wave to one another from opposite sides of the border. Frankly, we barely even email these days—how much is there to say when every day is now the same, and there is nothing to look forward to, save for more Netflix and another bag of chips.

I see now that my long-distance relationship is bringing no “health” to me during this pandemic. Yet, strangely, this very fact makes me even more committed to my lover than ever before, more patient and generous. Calm in the face of contingencies. This isn’t a virtue within me, nor a self-discipline. It feels more like a revelation, a surprising bit of benevolence in an otherwise cold and indifferent world. Yes, perhaps my stubborn insistence upon loving another without the guarantee of a return is nothing more than a perversity within the human spirit. A reckless, self-destructive impulse in us that wants to throw ourselves desperately into something only when it seems like a fruitless enterprise: the allure of heroism. Perhaps this is my own feeble and tragic assertion of free will in the face of our increasingly limited personal freedoms. Or maybe I just take a contrarian’s pride in rebelling quietly against the cultural norms that celebrate “self-love” as the highest form of enlightenment, my own little futile act of subversion against modern wellness and self-affirming culture. Or, perhaps these forced circumstances of extended unhappy waiting have caused me to accidentally experience something that only poets and not modern wellness gurus can truly describe: a love that moves beyond limits of time and distance and self. As Shakespeare wrote, “Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, / But bears it out ev’n to the edge of doom.”

What is a relationship for? It is sometimes for having a partner with whom to shoulder the domestic yoke. It makes sense, and it works. Sometimes a relationship is just for fun, a way to blow off steam, and feel less alone. But at other times maybe a relationship does not make sense, and isn’t for anything. Love just is. It is serendipitous, and real, profoundly selfless and entirely unearned. Maybe during this time of crisis and uncertainty I have, through no virtue of my own, been lucky enough to discover love growing and deepening within me. To the more cynical this might still sound like self-love, or at the very least self-improvement. But it isn’t experienced like that, as a choice to become a better person. No, if anything I’m angry at myself to discover that this love is so impractical, and so opposed to my own self-interests. This relationship is not meeting my needs, or assuaging my insecurities, or contributing to my wellbeing. Love, it turns out, remains an enduring mystery. In this time of solitude and loneliness, I am content to sit in the company of poets, and wait.