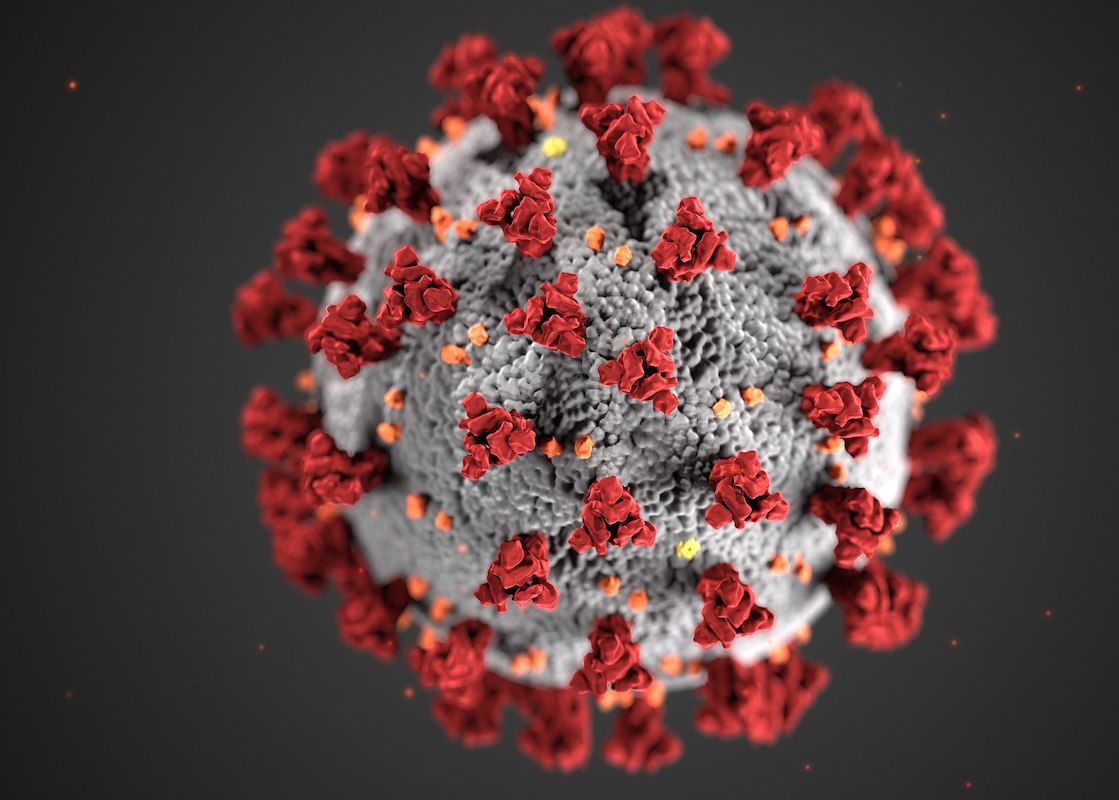

COVID-19

China: Exploiting False Accusations of Racism

When confronted, China frequently accuses its critics of racism. Last month, for example, Beijing expelled three Wall Street Journal reporters in retribution for an opinion column titled “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia.” China Daily, a Communist Party mouthpiece, declared the headline “astonishingly racist”—despite the fact the term “sick man” is routinely used idiomatically to describe countries facing economic challenges, and isn’t connected to the Coronavirus outbreak.

In January, the Chinese embassy in Denmark demanded an apology after a Danish newspaper printed a cartoon related to the Coronavirus outbreak: a Chinese flag with virus icons where the stars should be. Embassy staff stated flatly that the cartoon “is an insult to China and hurts the feelings of the Chinese people.” In 2018, similarly, China’s ambassador in Ottawa said Canada’s arrest of a politically connected Chinese tech executive was motivated by “white supremacy.” (Beijing then retaliated by arresting two Canadians in China.)

To be clear, the Coronavirus outbreak truly has led to some racist attacks on Chinese people (and other Asians) around the world. The specter of an epidemic often brings out the worst in us. And even in the best of times, xenophobes need little provocation to rail against foreigners. Such prejudice is unacceptable, and should be condemned.

Yet we must also be aware that the Chinese government has learned to weaponize our own progressive tendencies, and has learned to exploit false accusations of racism against democratic societies. Ironically, this same Chinese regime encourages racism and xenophobia domestically.

Government-controlled Chinese media routinely stirs up nationalist hostilities. And Chinese television frequently plays on racial stereotypes. China’s biggest Lunar New Year television show, with an audience in the hundreds of millions, in 2018 featured skits with a black man playing a monkey and a woman in blackface with a huge posterior. In one 2016 ad for laundry detergent, a Chinese woman stuffed a detergent pod into a black man’s mouth and shoved him into a washing machine. Out popped a pale-skinned Chinese man.

In 2017, during one of its recurrent border disputes with India, China’s largest press agency, Xinhua News, released a video starring an exaggerated Indian caricature to parody China’s adversaries. And an anchor on Chinese Central Television (CCTV) said on air in 2012 that China needs to “clean out foreign trash, wipe out foreign snake heads, root out foreign spies, kick out foreign shrews, and to make those who demonize China shut up and fuck off.”

The Global Times, a state media outlet, is well known for inflammatory, offensive editorials about foreign countries. One declared that should Australia continue flights over the South China Sea “it would be a shame if one day a plane fell from the sky and it happened to be Australian.”

Chinese social media are hardly more polite. In late February, the Chinese government published draft rules to make it easier for foreigners to obtain permanent residency in China. The proposed regulations stirred a huge backlash on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter. On Twitter itself (which is formally blocked in China), Chinese opposition expressed itself in forceful and profane terms such as “foreign trash” (often specifically aimed at Muslims), “white pigs” and the n-word.

China has been pursuing an ambitious trade and infrastructure program all over the world, especially in Africa. In Kenya, so many accusations of deliberate racism, segregation, and abuse by Chinese workers and companies were reported that the Kenyan Ministry of Labor started an official probe. In 2015, China kidnapped and jailed a Swedish bookseller for “illegal business operations” because he sold publications Beijing disapproved of. He was sentenced last month to 10 years for “illegally providing intelligence overseas,” in spite of a lack of evidence. In response to Sweden’s ongoing protests of the situation, China’s ambassador in Stockholm threatened that “we treat our friends with fine wine but for our enemies we have shotguns.”

It is important that Western governments and citizens take a stand against anti-Chinese xenophobia. But the West also should be careful to ensure that accusations of intolerance are not merely a smokescreen put up by Beijing’s hypocritical authoritarians.