Art

The Balkanization of Art

How is art meant to happen when everyone is supposed to be thinking the same thoughts? Art goes against the grain. It’s the sand in the oyster that creates the pearl.

Art is primal. Necessary. Emerging from some deep, ineradicable human need, art has been an integral part of human society from the time humans sought shelter in caves. And since that time, art has been a means of exerting social control in ways both subtle and bold. In ancient Egypt the architecturally marvellous pyramids were designed to strike awe in the hearts of the slaves lugging the bricks, thereby reinforcing their lowly place in the universe and making them more tractable in the process. The Renaissance popes conscripted into their service anyone who knew how to wield a paintbrush and put them to work exalting Christian cosmology. As for Stalin, he corralled every writer (a notoriously cantankerous group) who wanted to earn a living by the pen into the Soviet Writers Union, where their raison d’être became the glorification of the state.

America was meant to be different, a beacon for people fleeing from dogma, a place where the collective project was that of creating a society where everyone could be an individual—nirvana for artists. From the poet Walt Whitman (“Song of myself”!) to the painter Georgia O’Keefe to the photographer Robert Frank, artists in America have been free to pursue their personal vision. If they chose to exalt the status quo, like Steven Spielberg, they won Oscars. Should they want to smash it, in the manner of Allen Ginsburg, they were given the National Book Award. But something fundamental has shifted, and the arts in America are lately meant to serve a specific moral or didactic purpose. That is not to say any artist can no longer write, paint, or photograph what they like. But unless artists and writers follow certain precepts, they decrease the chances that their work will be reviewed in prominent media outlets, talked about in the right postal codes, or considered part of the bien-pensant cultural conversation.

As an American novelist, it is risky for me to write the sentence you just read. Why should this be so? It is no secret that the American cultural temple is a liberal project. I believe that is to be applauded, and I say this as one whose own views are generally liberal. If someone has to control the culture, I’d rather it was liberals than the National Rifle Association. Unfortunately, this situation comes with a downside which is homogeneity. As Hegel would tell you (thesis, antithesis, synthesis), when everyone agrees, progress becomes more difficult to achieve. How is art meant to happen when everyone is supposed to be thinking the same thoughts? Art goes against the grain. It’s the sand in the oyster that creates the pearl.

Let’s take Hollywood as an example. It is a truism that the culture of Hollywood is liberal, but not liberal in the sense of freethinking. Perhaps you are considering writing a screenplay. Knowing the political orientation of the producers to whom you will be trying to sell your work, what would you do? Of course, there is the occasional producer who values complexity, but what you would probably do, because nearly everyone does, is leave complexity at the curb and write something that reinforces the outlook of those who are signing the checks.

We see a similar phenomenon in publishing, at least when it comes to literary fiction. If an author creates a protagonist who questions liberal pieties (not condemns, mind you, but simply questions), he will risk creating a barrier to the work being subject to critical consideration. In a world where critical approbation is necessary to sell books, this is not a happy state of affairs. Elucidate the interiority of that protagonist and the problem becomes exponentially worse. In contemporary American literature, there is no Michel Houellebecq, because the current conditions do not allow for it. New York publishers will avoid a novelist who writes about Islam the way Houellebecq does; critics would either ignore or lambast them. A novel like Submission can only be published by a major American publisher because Houellebecq is not an American.

There is another salient aspect of liberalism today and culturally it is perhaps the most important one of all—the privileging of groups that have previously been excluded from power whether female, black, Latino, Asian, gay, or any other historically marginalized peoples. On the surface, this seems to be an entirely positive development. Let’s call the phenomenon “radical inclusiveness.” But it is this feature of the current liberal project that has so troubled the arts. In an unwritten cultural fiat, writers are granted “standing,” as in an author does, or does not have the “standing” (or, is allowed) to tell a particular story. An inverted hierarchy has developed whereby those who suffered from exclusion are now on top and those who did the excluding (metaphorically, at least; one presumes these artists didn’t exclude anyone individually) are on the bottom. Chinese-American author Amelie Wen Zhao postponed publication of her novel Blood Heir when she was accused of racism for writing insensitively about slavery (in a fantasy novel!). Award-winning author Kristine Kathryn Rusch decided to self-publish her novels about a black detective because of the degree to which she, as a white woman, was discouraged by traditional publishers from writing about a black character.

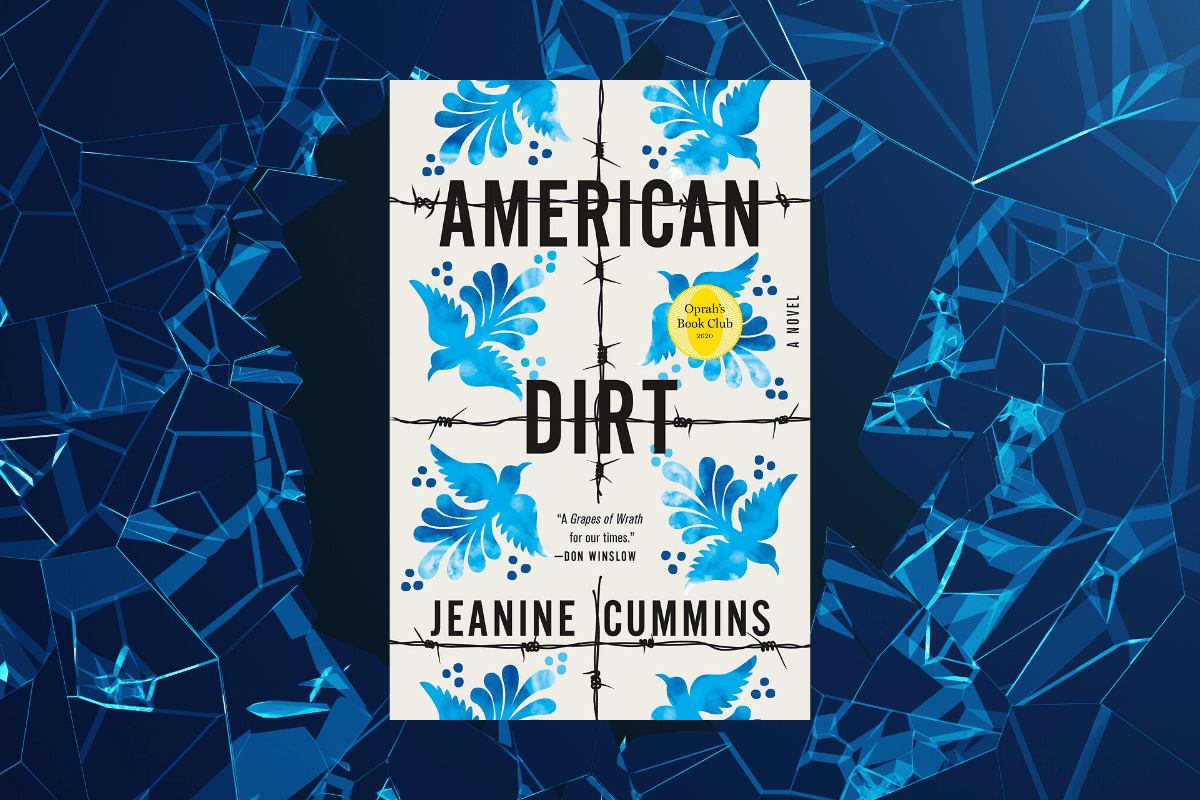

Right now, a controversy is raging about the new novel American Dirt, written by Jeanine Cummins, an author of mixed Irish and Puerto Rican descent (one of her grandparents was Puerto Rican), who has long identified as white. The book, for which the author received a million-dollar advance, tells the story of migrants journeying through Mexico toward the American border. Despite doing copious amounts of research, Cummins was so concerned about being unqualified to write the book that she expressed this fear in a guilt-ridden “Author’s Note” that follows the fictional text in the actual book. “I wished someone browner than me would write it,” she laments. Large swaths of the literary community agreed with her assessment and Cummins has been viciously attacked on social media for having the audacity, as a white woman, to write about the migrant experience (there are those who say the book itself is not very good but that is the subject of another essay). Her publisher was so intimidated by the vitriolic response that her promotional book tour was cancelled because of fears for the physical safety of the author and of booksellers. The novelist Lauren Groff, who favorably reviewed American Dirt for the New York Times, fretted that, “I was sure I was the wrong person to review this book. I could never speak to the accuracy of the book’s representation of Mexican culture or the plight of migrants; I have never been Mexican or a migrant.” If the goal is a capacious literary culture, writers flagellating themselves over who is entitled to write what does not produce optimal results.

In 2016, the author Lionel Shriver, a white female, delivered a speech at a literary festival in Australia during which she donned a sombrero to underscore what she took to be the unfairness of the principle that so distressed Cummins and Groff, that only members of a particular group should be allowed to write about that group. And while it is difficult to endorse her sartorial choice, I am in wholehearted agreement with Shriver’s thinking. Nothing is more prized today than authenticity, which currently exists on a higher plane than talent. You can see the problem. Or perhaps you can’t. We can disagree and still co-exist which is how democracy works.

The same problem roiled the art world at the Whitney Biennial of 2017, at which the artist Dana Schutz had the temerity to exhibit a painting of Emmitt Till. Till was a black teenager lynched in Mississippi after he was falsely accused of whistling at a white woman. His death was a tragedy for the entire nation. Schutz’s powerful canvas depicts the slain boy in his coffin. The painting was unveiled; an uproar followed. The Internet predictably vituperated. Protesters linked arms in front of the work to impede the view of museum-goers. Schutz’s crime? Creating this undeniably potent work of art while being a member of the wrong race.

Why is all this happening now? The assault on liberal values represented by the ghastly presidency of Donald Trump is perceived by much of the creative community as an existential danger, and with nervous systems on high alert, this has understandably led to a certain amount of reductive thinking. Artists are in no mood to cede an inch of territory in the struggle. Groups under threat retreat into their own silos where they take comfort in the company of likeminded people. While the “melting pot” was always a bit of an American myth, for much of the post-WWII era it represented an aspiration, an ideal vision of society. In America today the peril in making one’s particular ethnic heritage (or membership in any group defined by a single characteristic) the most prominent feature of one’s identity is that we will no longer identify primarily as Americans. Ironically, it is liberal universalism that will ultimately suffer, and when liberal universalism suffers, then non-didactic art—art that exists for a higher purpose—is on the chopping block.

There is nothing inherently wrong with creative work that is informed by identity or by politics but, for me at least, the most powerful art remains that which is primarily imbued with the artist’s humanity. Were a brilliantly talented African-American artist like Kerry James Marshall or Kara Walker to create a work of art commemorating the victims of the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre we should all consider it a mitzvah.

This article originally appeared in Le Monde.