recent

Black or White, It's the Same Old Anti-Semitic Pathology

Unlike the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooter or the 2019 Poway synagogue shooter, the suspects in these attacks weren’t white supremacists.

Last year closed with a number of anti-Semitic attacks in the New York City area—including the killing of three people at a Jersey City kosher market by two shooters who had expressed interest in the fringe Black Hebrew Israelite movement, and a machete attack at a rabbi’s home in Monsey, NY by a suspect who appears to have referenced the same anti-Semitic hate group in his rambling manifesto.

Unlike the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooter or the 2019 Poway synagogue shooter, the suspects in these attacks weren’t white supremacists. Black Hebrew Israelite ideology is an exclusively black movement, whose various sects typically preach that black people are the true descendants of Biblical Israelites, and that today’s (actual) Jews are frauds. The Black Hebrew Israelites do not constitute a mainstream religious group, and certainly do not represent the views of ordinary American blacks. Nevertheless, the possibility that these crimes may be connected to Black Hebrew Israelite beliefs has elicited an uncertain reaction from public officials and commentators, who are more familiar (and comfortable) with discussions that center blacks as victims of bigotry than as bigots themselves.

Needless to say, black Americans should not be regarded as scapegoats for broader anti-Semitic currents within American society (of which the Black Hebrew Israelite phenomenon is but a niche component). Even the phrase “black anti-Semitism,” which sometimes appears in public discussion, seems misplaced, as its usage suggests some unique pathology distinct from “white anti-Semitism.” As the African-American Marxist academic Adolph Reed argued in a 1995 essay, “Black anti-Semites are no better or worse than white or other anti-Semites, and they are neither more or less representative of the ‘black community’ or ‘black America’ than Pat Buchanan, Pat Robertson, Tom Metzger—or your co-worker or roommate who whispers about ‘their’ pushiness and clannishness—are of white American gentiles.”

Rather, Reed elaborated, “Black Anti-Semitism’s specific resonance comes from its man-bites-dog quality. Black Americans are associated in the public realm with opposition to racism, so the appearance of bigotry among them seems newsworthy. But the newsworthiness also depends on a particular kind of racial stereotyping, the notion that on some level, all black people think with one mind…Any Black anti-Semite is seen not as an individual but as a barometer for the black collective mind.”

Anti-Semitism among black people, as among everyone else, comes in different guises. Some of it is old-fashioned Christian anti-Semitism. Some of it is political anti-Semitism of the type rooted in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and other venerable conspiracist hoaxes. And some of it is traceable to more modern leftist movements, which promote anti-Zionism in a way that can blur into classic anti-Semitic tropes that case Jews as inherently malevolent.

Black nationalists, such as the Nation of Islam and Black Hebrew Israelites, sometimes will integrate the paranoid, pathological aspects of anti-Semitism into a narrative centered on black identity: “They” are the ones who enslaved our ancestors; “they” are the ones who profit from the appropriation of black culture; “they” are the ones who conspired to get Malcolm X killed; and so on. But one could find corresponding claims in other manifestations of anti-Semitism, such as those promoted by white Christian survivalists or Arabs in the Middle East. These parochial details do not serve to define a wholly different species of anti-Semitism. They merely show how age-old conspiracist themes can be adapted into a narrative that suits a particular ethnic or political agenda.

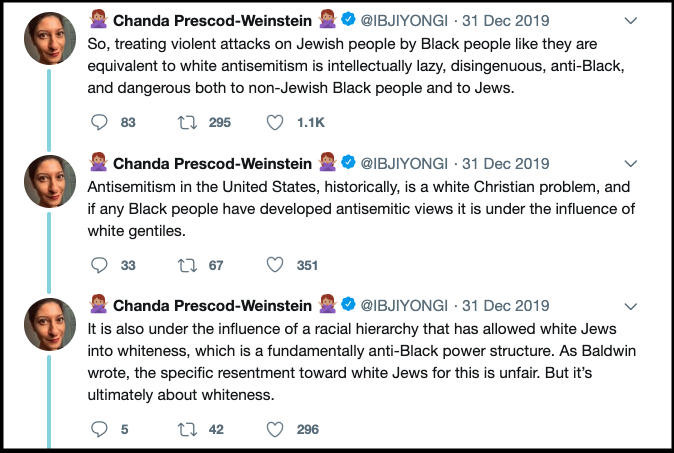

But this boring truth—that anti-Semitism reflects the same basic ideological malignancy, no matter who is spreading it—is apparently unpalatable to some progressives. This includes University of New Hampshire scientist and activist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, who recently wrote a controversial, widely commented-upon Twitter thread in which she declared that “treating violent attacks on Jewish people by Black people like they are equivalent to white antisemitism is intellectually lazy, disingenuous, anti-Black, and dangerous both to non-Jewish Black people and to Jews.”

She added that “antisemitism in the United States, historically, is a white Christian problem, and if any Black people have developed antisemitic views it is under the influence of white gentiles,” and that American Jews are beneficiaries of “whiteness,” which she describes as “a fundamentally anti-Black power structure.” Moreover, “Black people become distracted by Jewishness and don’t properly lay blame on whiteness and Jews get attacked in the process. It is a win-win for white supremacy.”

It’s hard to know what to do with all this except to say that a Jew hacked or shot to death by an anti-Semite is a Jew hacked or shot to death by an anti-Semite. It doesn’t matter what colour they are or how much the killer or victim has internalized the idea of “whiteness.” A hate murder is still a hate murder. (Prescod-Weinstein notes that the Monsey, NY suspect had “a documented history of serious, delusional mental illness.” This is true. But it should be noted that when white-nationalist perpetrators are accused of similarly horrific hate crimes, mention of mental illness often is avoided or downplayed, since no one wants to be seen as minimizing the role of racism.)

As for Prescod-Weinstein’s claim that Black anti-Semitism must somehow be caused by “the influence of white gentiles,” that is an incredibly condescending view, for it denies black people their own agency. In reality, blacks are no different than whites: Some succumb to hatred, while others do not. Yet Prescod-Weinstein promotes a collectivist view of blacks as child-like noble savages who retain their purity and innocence until white people contaminate their minds.

This strain of thinking isn’t confined to just this single New England-based race activist, but typifies the fashion for sermonizing about “whiteness” that one now commonly sees in academia and social media. Increasingly, “whiteness” is presented quasi-mystically—as a sort of secular equivalent to the religious concept of original sin. As such, it is presented as supernatural and trans-historical, existing outside of politics and the material world, virtually beyond the realm of sociological study.

The problem with fetishizing whiteness (and the white supremacist system we supposedly all inhabit), even beyond the way it fills public discourse with the sort of nonsense emitted by Prescod-Weinstein, is that it inspires a spirit of fatalism. Racism becomes a mystically evil force that is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Black people are helpless victims who can be programmed like robots to do anything—even to hate Jews. By undermining black autonomy and promoting a spirit of racial determinism, progressive activists are undermining the very methods black people use every day to transform their lives and defeat racism.

After lecturing black people about how they are “allowing themselves to be distracted by a false narrative rather than girding themselves to do the hard work of truly fighting white supremacy,” Prescod-Weinstein advises them to “keep their eyes on the prize,” and, tells them that “combatting white supremacy must involve unpacking why you think someone’s Jewishness is the meaningful signifier of why they did something. Do you mean their whiteness? Say whiteness then. Don’t be bamboozled by white Christianity.” The idea here, insofar as I understand it, is that it’s okay for blacks to offer a posture that is defensive, or even explicitly bigoted, so long as they make it clear that it is inspired by whiteness as opposed to Jewishness.

In other words, Prescod-Weinstein is arguing for replacing one identitarian framework with another identitarian framework, when the real problem is the identitarian trap itself.

One reason why anti-Semitism seems to be on the rise is that the tribalized nature of modern discourse, especially as filtered through social media, transforms economic and political problems into questions of culture and identity. When society is viewed as a collection of finely defined identity blocs, and social conflicts are framed as fights among those blocs, all variants of anti-Semitism are likely to become more prominent. If we want to combat this scourge—and all other forms of bigotry—the best approach is simply to stop using markers of identity as proxies for victimhood or moral worth.