Must Reads

Rich Like Me: How Assortative Mating Is Driving Income Inequality

The top decile of young male earners have been much less likely to marry young women who are in the bottom decile of female earners.

It may be useful to open this topic with an anecdote. Some ten years ago, I found myself in an after-dinner conversation, lubricated by wine, with an American who had been educated at an Ivy League college and was then teaching in Europe. As our conversation drifted toward matters of life, marriage and children, I was initially surprised by his statement that whoever he had married, the outcome in terms of where they lived, what type of house they owned, what kind of holidays and entertainment they would enjoy, and even what colleges their children would attend would be practically the same. His reasoning was as follows: “When I went to [Ivy League institution], I knew that I would marry a woman I met there. Women also knew the same thing. We all knew that our pool of desirable marriage candidates would never be as vast again. And then whomever I married would be a specimen of the same genre: They were all well-educated, smart women who came from the same social class, read the same novels and newspapers, dressed the same, had the same preferences about restaurants, hiking, places to live, cars to drive and people to see, as well about how to take care of the kids and what schools they should attend. It really made almost no difference socially whom among them I married.”

Trend Guessing Quiz: Assortative Mating Over Time

And then he added, “I was not aware of that at the time, but I can surely see it now.”

The story struck me then and stayed in my mind for a long time. It contradicted the cherished myths that we are all deeply different, unique individuals, and that personal decisions such as marriage, which have to do with love and preferences, matter a lot and have a big effect on the rest of our lives. What my friend was saying was precisely the opposite: He could have fallen in love with A, or B, or C, or D, and ultimately would have ended up in virtually the same house, in the same affluent neighborhood—whether in Washington, D.C., Chicago or Los Angeles—with a similar set of friends and interests, and with children going to similar schools and playing the same games. And his story made a lot of sense.

Of course, this scenario assumed that people who attended the same college would couple up. Had he dropped out of college, or not found anyone suitable to marry there, the outcome might have been different (say, a house in a less affluent neighborhood). His story dramatically illustrates the power of socialization: Almost everyone at the top schools comes from more or less equally affluent families, and almost everyone adopts more or less the same values and tastes. And such mutually indistinguishable people marry each other.

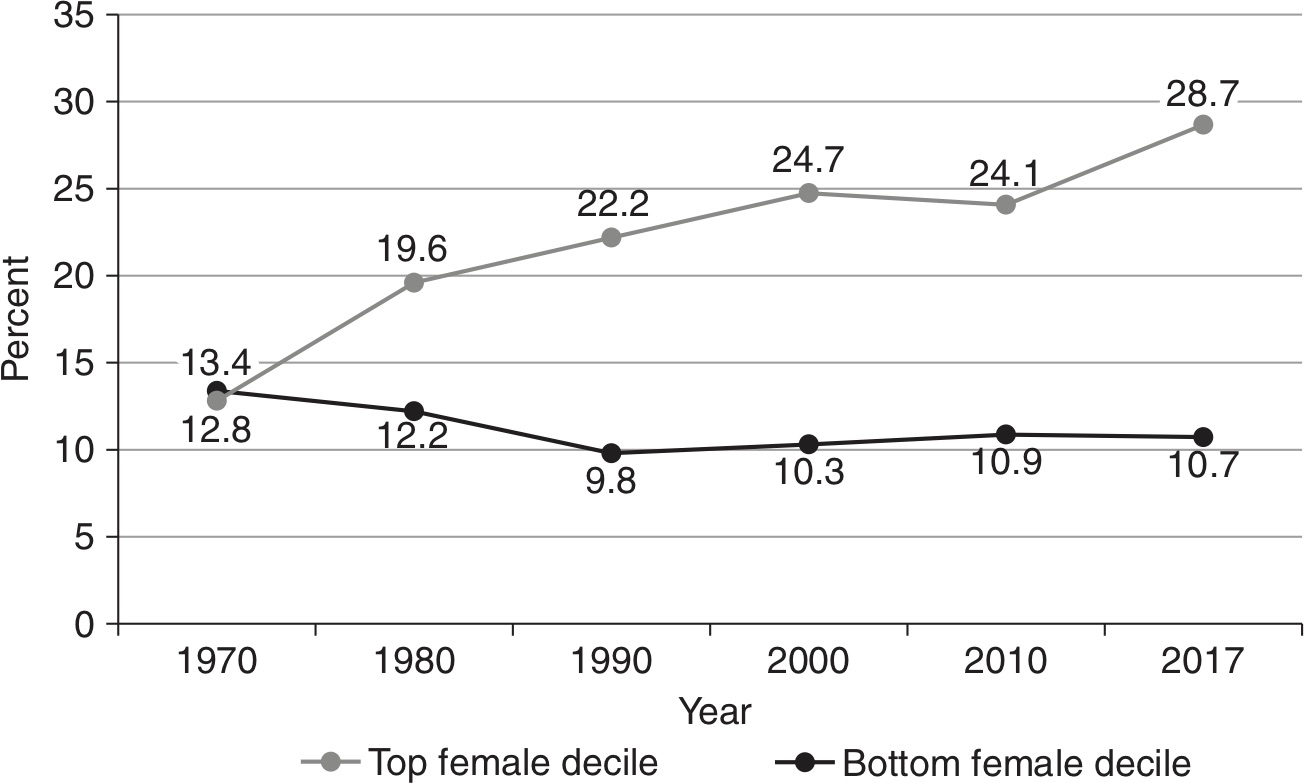

Recent research has documented a clear increase in the prevalence of homogamy, or assortative mating (people of the same or similar education status and income level marrying each other). A study based on a literature review combined with decennial data from the American Community Survey showed that the association between partners’ level of education was close to zero in 1970; in every other decade through 2010, the coefficient was positive, and it kept on rising. A different database provides another perspective on this trend; it looks at marriage statistics for American women and men who married when they were “young,” that is, between the ages of twenty and thirty-five. In 1970, only 13 percent of young American men who were in the top decile of male earners married young women who were in the top decile of female earners. By 2017, that figure had risen to almost 29 percent.

Percentage of U.S. men aged 20 to 35 in the top male decile of labor earnings who married women aged 20 to 35 in the top and bottom female deciles by labor earnings, 1970–2017

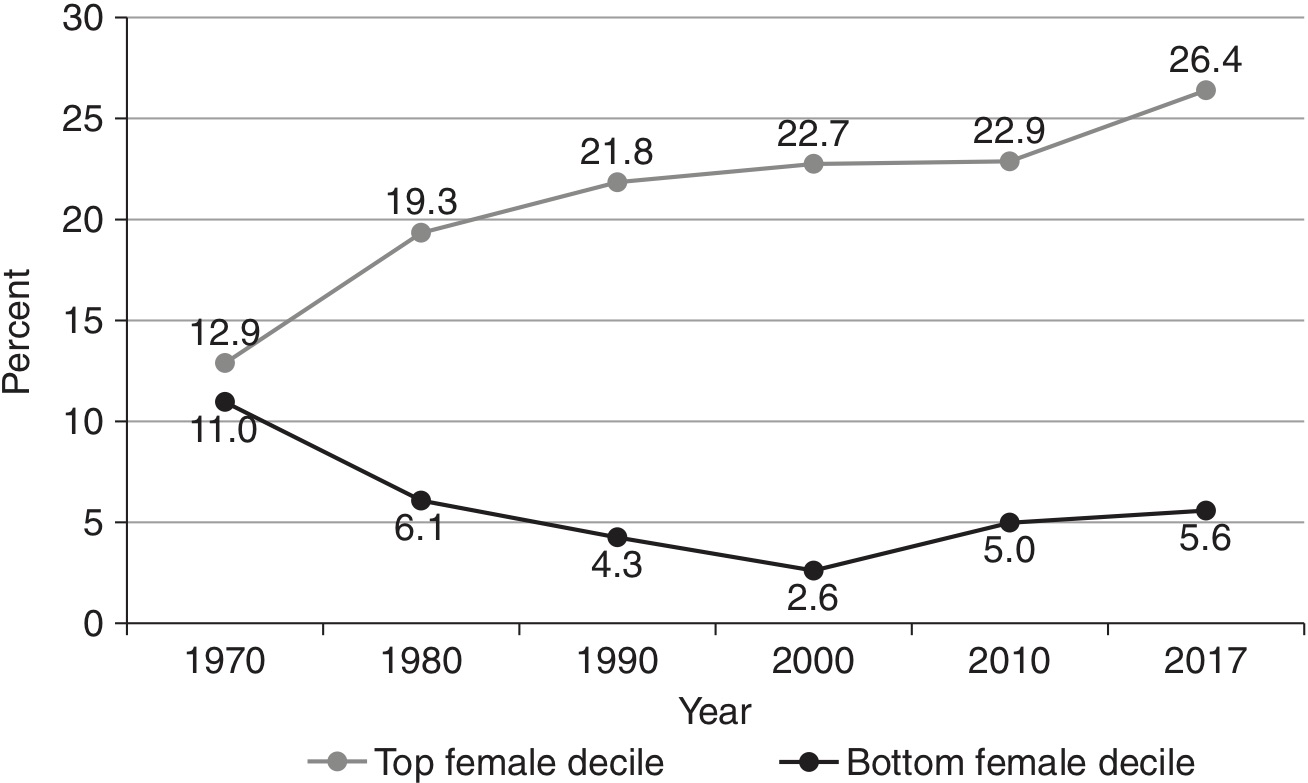

At the same time, the top decile of young male earners have been much less likely to marry young women who are in the bottom decile of female earners. The rate has declined steadily from 13.4 percent to under 11 percent. In other words, high-earning young American men who in the 1970s were just as likely to marry high-earning as low-earning young women now display an almost three-to- one preference in favor of high-earning women. An even more dramatic change happened for women: the percentage of young high-earning women marrying young high-earning men increased from just under 13 percent to 26.4 percent, while the percentage of rich young women marrying poor young men halved. From having no preference between rich and poor men in the 1970s, women currently prefer rich men by a ratio of almost five to one.

Percentage of women aged 20 to 35 in the top female decile by labor earnings who married men aged 20 to 35 in the top and bottom male deciles by labor earnings, 1970–2017.

In a very ambitious 2017 paper, Pierre-André Chiappori, Bernard Salanié and Yoram Weisstried tried to explain both the rise of assortative mating and the increasing level of education among women (which contrasts with a lack of increase in educational attainment for men). They argued that highly educated women have better marriage prospects, and thus, there is a “marriage education premium,” which is perhaps as important as the usual skill premium that education provides. While the skill premium is, in principle, gender neutral, the marriage education premium is, the authors argue, much higher for women. Underlying this must be greater “pure preference” for homogamy among men because if that did not exist, the rising education level of women might be as much of a deterrence in the marriage market as an attraction.

There is a further link between, on the one hand, assortative mating, and, on the other hand, increasing returns to investment in children, which only more educated couples are able to provide. They can, for example, expose their children to a learning-conducive atmosphere at home and introduce them to cultural experiences that less-educated parents may have little interest in (concerts, libraries, ballet), as well as to elite sports. The importance of linking these seemingly unrelated developments—women’s education, greater work participation by women, assortative marriage patterns, and the increasing importance of early childhood learning—is that it illuminates one of the key mechanisms of within-generation creation of inequality and its intergenerational transmission. If educated, highly skilled, and affluent people tend to marry each other, that by itself will tend to increase inequality. About one-third of the inequality increase in the United States between 1967 and 2007 can be explained by assortative mating, according to research by Koen Decancq, Andreas Peichl and Philippe Van Kerm. For countries in the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), assortative mating accounted for an average of 11 percent of increased inequality between the early 1980s and early 2000s.

But if, in addition, the returns to children’s early education and learning are sharply rising, and if these early advantages can be provided only by very educated parents, who, as the data show, spend much more time with their children than less educated parents, then the road to a strong intergenerational transmission of advantages and inequality is wide open. This is true even if—and it is important to underline this—there is high taxation of inheritance, because inheritance of financial resources is merely one of the advantages that the children of educated and rich parents enjoy. And in many cases, it may not even be the most important part. (Although, as I argue elsewhere, taxation of inheritance is a particularly good policy for leveling the playing field and increasing equality of opportunity, it is an illusion to believe that such taxation will by itself be sufficient to equalize the life chances of children born to rich and poor parents.)

High income and wealth inequality in the United States used to be justified by the claim that everyone had the opportunity to climb up the ladder of success, regardless of family background. This idea became known as the American Dream. The emphasis was on equality of opportunity rather than equality of outcome. It was a dynamic, future-oriented concept. Joseph Schumpeter used a nice metaphor to explain it when he discussed income inequality: We can see the distribution of incomes in any one year as being like the distribution of occupants who are staying on different floors of a hotel, where the higher the floor, the more luxurious the room. If the occupants move around between the floors, and if their children likewise do not stay on the floor where they were born, then a snapshot of which families are living on which floors will not tell us much about which floor those families will be inhabiting in the future, or their long-term position. Similarly, inequality of income or wealth measured at one point in time may give us a misleading or exaggerated idea of true levels of inequality and can fail to account for intergenerational mobility.

The American Dream has remained powerful both in the popular imagination and among economists. But it has begun to be seriously questioned during the past ten years or so, when relevant data have become available for the first time. Looking at twenty-two countries around the world, Miles Corak showed in 2013 that there was a positive correlation between high inequality in any one year and a strong correlation between parents’ and children’s incomes (i.e., low income mobility). This result makes sense, because high inequality today implies that the children of the rich will have, compared to the children of the poor, much greater opportunities. Not only can they count on greater inheritance, but they will also benefit from better education, better social capital obtained through their parents, and many other intangible advantages of wealth. None of those things are available to the children of the poor. But while the American Dream thus was somewhat deflated by the realization that income mobility is greater in more egalitarian countries than in the United States, these results did not imply that intergenerational mobility had actually gotten any worse over time.

Yet recent research shows that intergenerational mobility has in fact been declining. Using a sample of parent-son and parent-daughter pairs, and comparing a cohort born between 1949 and 1953 to one born between 1961 and 1964, Jonathan Davis and Bhashkar Mazumder found significantly lower intergenerational mobility for the latter cohort. They used two common indicators of relative intergenerational mobility: rank to rank (the correlation between the relative income positions of parents and children) and intergenerational income elasticity (the correlation between parents’ and children’s incomes). Both indicators showed an increase in correlation between parents’ and children’s incomes over time (rank to rank increased from 0.22 to 0.37 for daughters and from 0.17 to 0.36 for sons, and intergenerational income elasticity increased from 0.28 to 0.52 for daughters and from 0.13 to 0.43 for sons). For both indicators, the turning point occurred during the 1980s—the same period when U.S. income inequality began to rise. In fact, three changes happened simultaneously: increase in inequality, increase in the returns to education, and increase in the correlation between parents’ and children’s incomes. Thus, we see that not only across countries, but also across time, higher income inequality and lower intergenerational mobility tend go together.

So far, we have only looked at relative mobility. We should also consider absolute intergenerational mobility, that is, the change in real income between generations. Here, too, we see a decline: absolute mobility in the United States declined significantly between 1940 and the 2000s, as a result of a slowdown in economic growth combined with increased inequality. We should keep in mind that absolute mobility is very different from relative mobility, since it depends largely on what happens to the growth rate. For example, absolute mobility can be positive for everyone if the income of every child exceeds the income of their parents, even if the parents’ and children’s positions in the income distribution are exactly the same. In this example, complete intergenerational absolute mobility would coincide with a complete lack of intergenerational relative mobility.

Excerpted from Capitalism, Alone: The Future Of The System That Rules The World, by Branko Milanovic, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.