Memoir

Memories of Life at Kingdom Hall: An Alberta Schoolgirl Waits for Armageddon

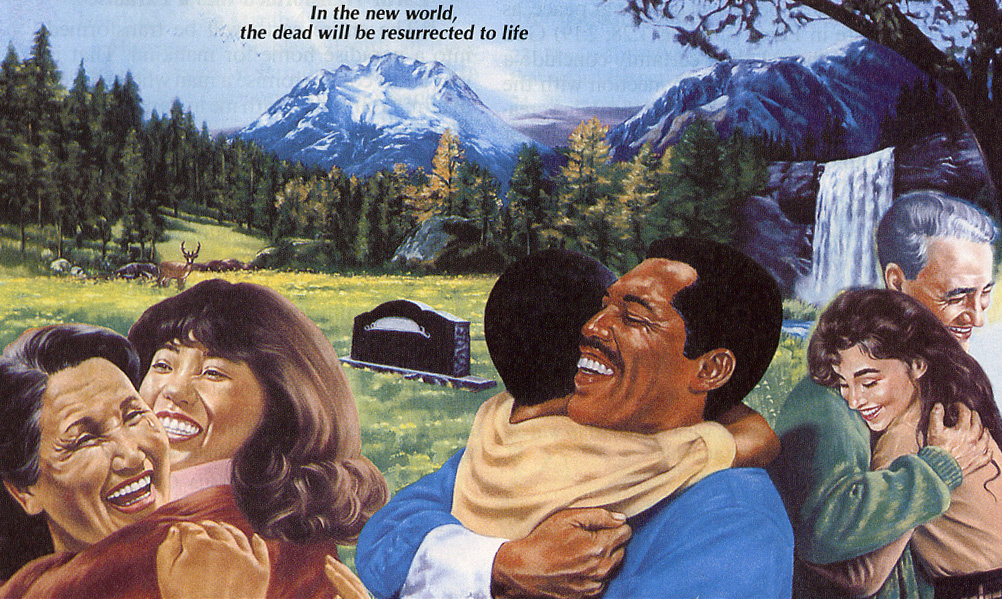

Paradise was as real to us as a memory—and even though it wasn’t something concrete, our minds were already there in it.

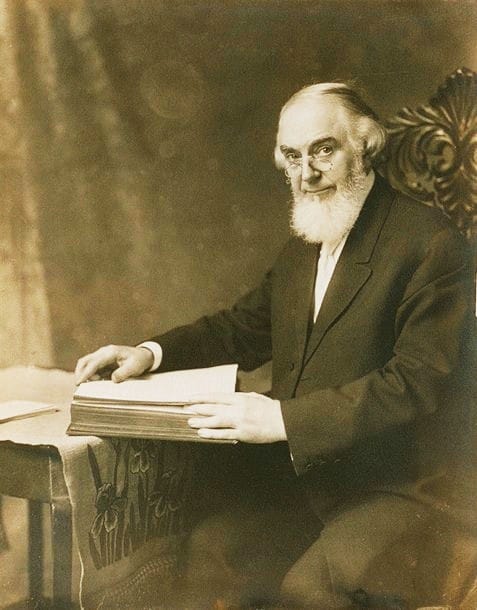

In 1909, a wealthy man from Pennsylvania bought a brick building on a steep street just south of the Brooklyn Bridge, across the river from Manhattan. Blocks away from where Walt Whitman had set to type the first editions of Leaves of Grass, a small, relatively unknown group that called themselves the “Bible Students” was regrouping, with this building as their hub.

Their leader was feeling discouraged after another failed prediction that the world would end. But he was not deterred. Spending his days overlooking the same East River that had inspired Whitman to write verse, he rewrote his own inspired prose that warned of the world’s imminent, violent end and urged all to join him so that they, too, could live forever in paradise on Earth.

Russell had always been interested in religion and as a young man had painted fire and brimstone Bible verses on fences around his hometown as a pastime. He met a man named William Miller, who had founded a religious movement, Millerism, which was the precursor to the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Russell found his own interest in apocalypse mirrored in Miller, who had used the prophecies in the book of Daniel to calculate the return of Christ. He joined the Millerites for a time, but after a series of distressing miscalculations and disappointments over being stood up by Jesus, Russell broke off and decided the only answer was to form his own sect. He used his father’s money to travel to the pyramids at Giza to see answers to the riddle of the last days.

Shortly after his volumes Studies in the Scriptures had been dispatched from the printery on Columbia Heights, he died. But his apocalypse was not extinguished with him. It, along with his money, was passed on to a series of successors, who, like him, were surprised at the close of each day to see the skyline of Manhattan still intact across the river. For the next hundred years, Armageddon did not come.

Like a home that fills up with comfortable clutter as the years pass, this group, which had been founded under Russell’s conviction that no organized religious structure was needed to find truth, flourished in limbo. It accumulated writings, doctrines, rules—and followers, millions of them. A hierarchy seemed to build itself without anyone noticing, and it became a bureaucracy that rivalled any large human institution.

A Governing Body anointed itself through God’s “holy spirit,” and eventually the eight male leaders who made up that group would, from their carpeted offices overlooking Manhattan, come to preside over almost every aspect of their followers’ spiritual, moral, and material lives. Children were born into this organization and grew up in it; the estates of people who were never supposed to grow old and die were left to it. Steady donations funded the accumulation of over 3.2-million square feet of property in Brooklyn Heights, much of it connected by a network of underground tunnels. From these buildings and printeries, the Governing Body, now referring to itself as the “Faithful and Discreet Slave,” oversaw what became one of the biggest publishing entities in the world.

As the years passed, and the portions of their lives in this old world dragged on as predictions of the world’s end in 1878, 1881, 1914, 1918, 1925, 1930, 1975, and more failed to materialize, the leaders edited the old editions of their publications to soften some of those proclamations. The believers took comfort in the words of Jesus that “regarding that day or that hour, only the Father in heaven knows,” and forgave the miscalculations of their leaders, knowing that the scriptures say the light gets brighter as the day draws near. Jehovah would progressively reveal the truth to his people at the time of the end.

By 1975, when another one the dates had come and gone, Russell’s small group of followers had morphed into a highly structured organization with followers so devoted they were willing to refuse blood transfusions even if it cost the lives of their own children, because they believed God forbade putting blood into their bodies, and to shun anyone, including members of their own family, who disagreed with the organization’s official teachings. To approximately eight million people on Earth today, this organization is the one true religion. And thanks to a genius rebranding effort in the 1930s by an ill- tempered, six-foot-eight-inch man named Joseph Rutherford, who proclaimed “Millions Now Living Will Never Die!,” this organization today has the name “Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

My grandparents on both my mother’s and father’s sides became Jehovah’s Witnesses when they were adults. My mother’s mother, Kay, already had two young children when an aunt of her husband, Jack, converted to the faith after a proselytizer came to her door in their prairie city. The aunt thereafter “witnessed” to Jack for years, attempting to convert him, to the point where he secretly became convinced that he had found the truth.

Yet my grandfather did not bring up the topic of religion until years later, when my grandmother—a very intuitive, independent, wise woman—had reason to suspect he was having an affair. When confronted about the purported dalliance, he knew full well that if he admitted it, my grandmother would leave him. So he denied the affair—to his deathbed—but to save his marriage, he said that the time had come for him and Kay to take the offer his aunt had made to study the Bible with them. Jack was no dummy himself, and though he had become convinced that the things his aunt was saying were truths, he also knew that the Jehovah’s Witnesses forbade divorce. The last thing he wanted was to lose his smart, sharp wife.

My grandmother, a schoolteacher, was not a submissive woman before she became a Jehovah’s Witness. Afterward, of course, she had no choice, but she finally agreed to my grand- father’s suggestion of a Bible study only under the condition that she was doing it to prove wrong these men who came to their house once a week to study the Bible.

For the next year, she spent two hours or so a week arguing with the men who sat in their living room, teaching her and her husband, who was largely silent. With great patience, they answered her questions and countered her arguments, using their books that had the answers to every question, and their kindness, which was unflappable, to win her over. And win her over they eventually did. The old Christmas decorations were abruptly dumped on the street for the garbageman, birthday parties were now forbidden as “pagan,” worldly family members were witnessed to, and if they rejected the truth, kept at arm’s length.

Now, instead of fighting, three times a week my grandmother put on her jewelry and heels, my grandfather donned the one tie he had purchased for the purpose, and the family piled into their boat of a car to drive through the frozen Alberta streets to the Kingdom Hall, where the brothers left their vehicles running in the parking lots so that their engine blocks would not turn to ice and refuse to start when it was time to return home again.

My mother, an extrovert, later told me that she never really believed all that they were saying at the meetings, at least not entirely, but that she enjoyed the social aspect of the congregation, the friends that she made there. My grandmother had always been harsh to her and critical, rejecting her for her brother, and she felt accepted by the warm embrace of the community. That brother, his mother’s favorite, on the other hand, never really took to things and left for the “world” when he was sixteen, moving out and becoming a drug dealer. That was what happened when you left, we were told, pointing to our uncle as a cautionary tale. People who left the truth became drug dealers and they went off to jail—as he did, many years later.

It was rare to meet a Witness who was not wholly committed, because this was not the kind of religion in which one could be a Sunday Christian. Paradise was as real to us as a memory—and even though it wasn’t something concrete, our minds were already there in it. We had allocated everyday existence its place but were in reality just waiting to live. And unlike the events in our memories, which no amount of pining could bring us back to, if we harnessed our individual nature and did what was right, we would keep the approval of our peers and our families and our community—but most of all, our God—and live forever in this coming paradise without any death, sorrow, sickness, or suffering.

The basic path for any Jehovah’s Witness is to marry young, and quickly, before the temptation to have premarital sex causes you to sin, and then, when and if children come along, to start their education in the truth young, to provide a buffer that will shore them up against the “world” that they would inevitably encounter when they started school (if Armageddon hadn’t come by then). This life prescription was laid out before us constantly—at meetings, at conventions, and by our parents.

But sometime after my older sister was born, my parents stopped going to the meetings. By the time I was born, two and a half years later, they had settled into a religious rut during which they attended just one meeting a year—the most important one, of course, the memorial of Jesus’ death—for fear that not to attend that one would seal all of our fates when Armageddon arrived. It wasn’t that they didn’t believe—they taught me that I was a Jehovah’s Witness, even though we rarely set foot in a Kingdom Hall or spoke to another Witness.

Though I was never told why, I can imagine reasons they stopped going regularly. For one thing, the Witness way of life is exhausting, and dragging two or three children to meetings in the evenings after bedtime or on the weekends is not a light demand. The weekends were for service, and if you didn’t go out preaching regularly, the elders would come and visit you to find out why. My father was also a very shy man, and I think he was most comfortable in his house, surrounded by his kids, his TV, and his wine. Socializing did not come naturally to him.

Growing up in this environment gave my brother and sister and me the worst of both worlds, in a way. We didn’t have the community we would have had if we had been Witnesses who attended meetings and service. But we also couldn’t go to birthday parties, and didn’t get Christmas presents. We had to leave the school gym during Christmas carol singalongs, and on hot-dog day, my mom had to bring special hot dogs for us, since the regular hot dogs might have blood by-products in them, and blood in any form could not be put into the body. It was mortifying. But in the unquestioning way of children, we knew that we were not like the other kids. They were going to die at Armageddon, and we, the special hot dog eaters, would live.

This was all we knew of life, and for a long time I thought that was how it was for all Witnesses. That was until second grade, when for Halloween, we were given an art project where we had to use orange and black construction paper to make a silhouette for the wall in some kind of Halloween theme. As a Witness, I did not celebrate this pagan holiday. But as an astute observer of the line between the religion that was a mystery even to me and gaining acceptance from my school peers, I chose to cut out an ambiguous owl on a branch in front of a full moon as my subject. In orange and black, next to the jack-o’-lanterns and ghosts, it wouldn’t telegraph “Bully her!” But if my parents happened to come in the room on parents’ night, no one could really say it was definitely a Halloween object.

Then came the day the teacher stapled all of the artwork to the corkboard, and as I scanned the orange and black paneling the wall, proud that mine was the only owl among a sea of jack-o’-lanterns and other Satan-objects, my eyes stopped on a strange rectangular black blob against an orange sky. On the blob, written in yellow chalk, were smeared the words “Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses.” What? I saw the name “Leesa” written at the bottom. It was the new girl. So she was a Witness, too. A real Witness, apparently, unlike me. It was strange to have an authentic one in the class, setting the bar suddenly, and I knew now that my owl, despite being one of God’s creations, showed me up for the imposter Witness I was. It did look a little spooky. When the teacher returned our art-works to us on November 1, I threw mine in the garbage.

Years later, when Leesa was sixteen, she got pregnant by a worldly boy and had to drop out of school. Situations like these sometimes seemed to occur more frequently for Witnesses, who had lived such sheltered, controlled existences compared with the population at large. A teenage Witness boy or girl is not taught about birth control, because it is taken as a given that they will not be having sex. When things went wrong, they seemed to go terribly wrong.

Excerpted, with permission, from Leaving The Witness: Exiting a Religion and Finding a Life, by Amber Scorah. Copyright © 2019 by Amber Scorah. Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Featured image: Jehovah’s Witnesses proselytizing literature, 2007.